Exhibition showcases treasures of St. Joseph’s Seminary

Founded in 1728, St. Joseph’s Seminary is one of Macao’s historical treasures. Indeed, the church has been holding continuous Christian services longer than any other church in greater China.

Now visitors can view “Treasure of Sacred Art of St. Joseph’s Seminary,” an exhibition of its many treasures. Three years in the making, this permanent exhibition opened in early October 2016 and fills nine rooms over two floors with paintings, sculptures, religious vestments, vessels used in church services, books and documents.

“This is the history of the Catholic church and the history of Macao,” says Lilian Chan, researcher at the Museum of Macau and one of the organisers of the exhibition. “Our responsibility is to preserve these artistic pieces. The seminary is a very special place, and this exhibition tells the people of Macao and its visitors about its historical and cultural significance. The seminary and the priests who worked here have made an enormous contribution to Macao in terms of education, music, charity, printing, research, art and marine navigation. It has educated many outstanding members of the Catholic clergy over the last three centuries.”

A dramatic history of Western influence in the Far East

Founded in 1728 by Jesuit missionaries, St. Joseph’s Seminary was only the second religious entity to be established in Macao, following in the footsteps of St. Paul’s College. The seminary’s aim was to educate missionaries for the evangelisation of China. The adjoining St. Joseph’s Church was built in 1758 on an adjacent site.

The Society of Jesus, founded 1534 in Paris by Ignatius of Loyola and six companions, was officially approved by the Vatican in 1540. It was a pioneer in bringing the Christian religion and Western learning to China.

One of the first Jesuits to travel to Asia was Francis Xavier who went to Japan via Goa, Singapore and Malacca. He died of illness in 1552, at the age of 46, on Shangchuan island, Guangdong province. Although he never set foot in Macao, he nevertheless is patron saint of the Macao diocese. Xavier was canonised in 1662, and a bone from his arm is preserved as a religious relic above an altar in St. Joseph’s Church.

The first Jesuit missionary came to Macao in 1555, but it was the arrival of Italian priest Matteo Ricci in 1582 that really established a base for missions in China. In 1601, upon the invitation of the Wanli Emperor, 13th emperor of the Ming dynasty, Ricci became the first Westerner to ever enter the Forbidden City. He settled in Beijing and succeeded in establishing good relations with the Imperial Court. At the behest of the emperor, Ricci introduced astronomy, science and other elements of Western knowledge to the court and shared a European map of the world, a modern clock and western paintings, among others. He and his associates translated Euclid’s Elements and other Western classics into Chinese. They also researched Chinese culture and philosophy and translated Chinese works into European languages.

In 1723, the Yongzheng Emperor, 5th emperor of the Qing dynasty, expelled from China the Jesuits along with other missionary orders after Pope Innocent XIII refused to accept that Chinese reverence for ancestors and Confucianism were social, rather than religious, activities. Many of the banned missionaries found safe haven in Macao.

Here, the Jesuits established several charitable organisations, including the Holy House of Mercy, the St. Raphael Hospital and a home for lepers. During World War II, St. Joseph’s Seminary and other Catholic charities played a major role in providing food and shelter to the thousands who fled to Macao, which was the only place in east Asia unoccupied by the Japanese military.

Still, the Jesuit journey in Macao was not a smooth one. In 1762, the Portuguese authorities expelled them from the city and handed the seminary to the Lazarists. The Jesuits resumed control in 1890 but were expelled again after the Portuguese revolution of 1910. They were allowed to return only in 1930.

The seminary has educated many leaders of the Catholic church in China, including Domingos Lam and Jose Lai, both Bishops of Macao; Domingos Tang, the Archbishop of Guangzhou; and John Tong Hon, Cardinal and Bishop of Hong Kong.

It has also been a cradle of sacred music since the mid‑18th century, and throughout the years, its teaching staff has trained generations of musicians in Macao.

In 1931, it established the Colegio Diocesano de S. Jose, which has developed into a local education system from kindergarten to secondary school.

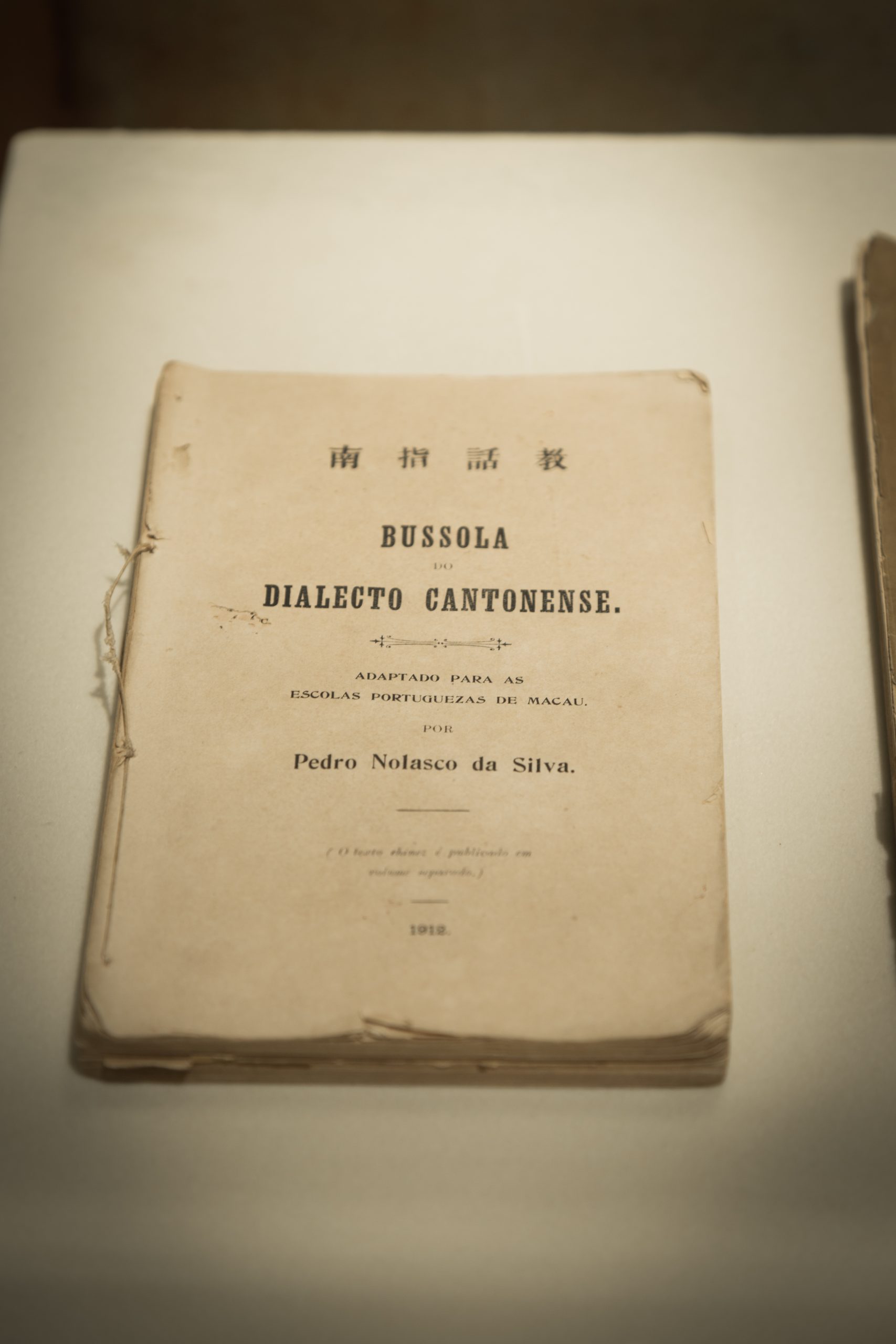

The seminary has also been a centre of publishing, one of the earliest in China, in fact. Of its many significant publications are dictionaries translating Chinese into European languages. These dictionaries and textbooks, as well as historical documents collected by the seminary, are preserved as cultural relics of Macao.

A diverse selection of sacred and secular items on display

All these different facets and historical roles of the seminary are highlighted in the exhibition, which includes a broad range of artefacts, from musical scores and instruments to artistic icons of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary.

Icons of locally‑revered saints are also on display, like that of St. Roch (1295–1327), a Frenchman who cared for patients afflicted with the plague. Unwilling to leave them in their suffering and also afraid he would pass on the disease to other people, St. Roch accepted death as inevitable. But according to legend, a dog visited him every day, bringing him bread, and he survived. It is said that in the early days when Macao was just a settlement, there were frequent cholera epidemics. The faithful prayed to St. Roch for help and the outbreaks disappeared. Subsequently, a street in the city is named after him: S. Roque.

The exhibition includes a large collection of dictionaries and textbooks compiled by the Jesuits, in both Mandarin and Cantonese. The Imperial Court of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) banned its subjects from teaching Chinese to foreigners, so Macao was the only place where Westerners could legally learn the local tongues. Of particular significance is a Chinese‑Portuguese dictionary compiled by Portuguese Lazarist Joaquim Afonso Gonçalves, a famous Sinologist, and published by the seminary in 1833. Forced to stay in Macao because of the Chinese court’s ban on religion, Gonçalves taught Chinese to foreigners, Latin to Chinese, and compiled dictionaries and language textbooks.

Various vestments and vessels used during religious services are also on display. Conservationists from the Museum of Macau spent three months cleaning and polishing the vessels with cotton wool to restore their original lustre. The vestments are decorated with the letters “JHS” and “HIS” – Greek and Latin symbols of the Jesuit order. “[The Jesuits] brought religious vessels with them from Europe. The ones that were made here introduced Chinese decorative features, resulting in a large number of delicate and sophisticated vestments and vessels,” says Chan.

A video describing the history of the seminary and some of the remarkable people who have lived and worked there plays as part of the exhibit. Historical photographs depicting the life of seminary students are also on display.

“When I designed this exhibition, I aimed it at ordinary people, not those with prior knowledge of Catholicism,” says Chan. “I want it to be accessible to everyone, so that everyone can understand the pieces. I used ordinary language, not terms specific to religion. On the weekends, we have many mainland visitors. Sometimes I come and help show them around.”

The exhibition features a small fraction of the seminary’s extensive collection. Across China, art and historical documents have often been destroyed or lost in fires, accidents, wars and revolutions. But five centuries of peace in Macao have preserved such important items for the future.

An old building proves challenging

Getting this exhibition up and running was no easy task. According to Chan, “It took three years to complete this project. We started in 2013.”

It was decided not to be held in a modern museum – of which there are many in Macao – but the seminary itself came with its challenges. While the seminary provides the most appropriate setting, the building itself is about 300 years old. “So we had many issues to deal with: the condition of the building, leaking water, air conditioning, etc,” recalls Chan. “Many of the valuable books cannot be displayed because they are not in good condition and must be treated with great care. There are some rooms in the seminary completely filled with old books.”

Most of the artefacts are displayed in heavy glass cases that weigh down the floors of the old building. “On the second floor, we couldn’t show too many pieces and chose showcases not made with glass but with acrylic that is light and durable. This is a long‑term exhibition.”

The exhibit is open to the public from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm every day except Wednesday. Admission is free, but a limit on the number of people viewing the second floor at any one time is strictly enforced for safety reasons.

Following a restoration overseen by the Cultural Affairs Bureau of the SAR government, St. Joseph’s Church received a UNESCO Asia‑Pacific Award for Culture Heritage Conservation in 2001. And in 2005, it was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as part of the Historic Centre of Macao.