Macao Museum of Art shines a spotlight on the Chinese master

Zhang Daqian stands as one of the greatest painters of the 20th century, a prodigious artist who produced an average of 500 pieces a year in a variety of styles. Zhang combined a wealth of influences with his mastery of traditional Chinese art to forge a unique style that continues to grow in popularity with pieces fetching high prices at auctions around the world.

On 23rd May, the Macao Museum of Art (MAM) opened an exhibition of 100 of his masterpieces. It will run until 6th August.

“Zhang was a great master in art, playing an indispensable role in the development and progress of Chinese fine art through the 20th century,” says Chan Kai Chon, director of MAM. “His artistic achievements have had a significant influence over subsequent generations of artists, especially his attitude and approach towards art study, his remarkable creativity, and the multiplicity of art forms he practised,” he explains.

The exhibition features works from Zhang’s prime, as well as his early years, on loan from the collection of the Sichuan Museum. They include his landscapes, portraits, line drawings, letters, seals, and the murals replicas produced during his time in Dunhuang.

Although the 100 pieces represent only a fraction of his vast output, they invite the public to experience the development of Zhang’s artistic vision through his early emulations of ancient works, the remarkable replicas of the Dunhuang murals in his middle period, and the representations of female beauty found in his later works, as well as the many seals he used. The exhibition is one of the 25 exhibitions and shows that comprise the 28th Macao Arts Festival.

Journey to greatness

Zhang was born on 10th May 1899 in Sichuan province in southwest China to an artistic family of modest means. His mother, Zeng Youzhen, and elder siblings served as his early art instructors. Like many artists, he learned by copying existing masterpieces and was especially influenced by the masters Shitao and Bada Shanren. His first commission came in his early teens when a fortune‑teller asked him to paint a new set of divining cards.

When he was 17, Zhang was on his way home from boarding school in Chongqing when he was captured by bandits. The gang leader ordered him to write a letter to his family to demand a ransom; he was so impressed by Zhang’s ability with the brush that he made the young man his personal secretary. During his three months of captivity, Zhang read books of poetry that the gang had stolen.

Zhang made his first trip abroad to Kyoto, Japan, where he studied textile‑dyeing techniques. He returned to China in the 1920s, working in studios in Beijing, Suzhou, and Shanghai, where he practised calligraphy under Li Ruiqing. In 1926, Zhang began visiting famous rivers and mountains throughout China, expanding his knowledge and appreciation of nature.

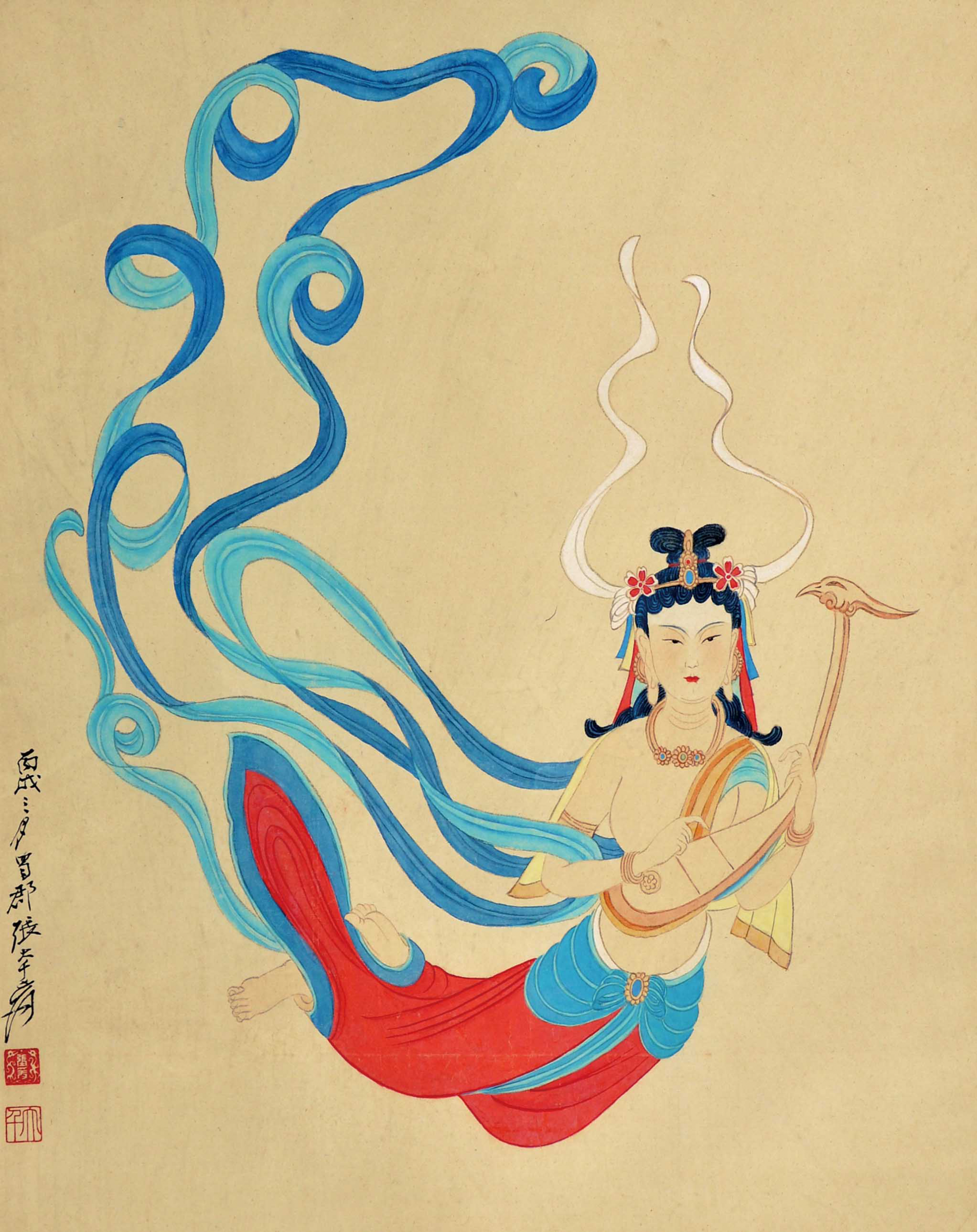

Zhang spent these early years focused on ink wash paintings, emulating his favourite masters before expanding to other great artists from the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties. In 1941, he left for Dunhuang in western China to study Buddhist mural paintings. His two years of study there proved pivotal; pieces from this period reveal an important shift toward a style heavy with colours.

Zhang mastered many styles throughout his long career, from meticulous and detailed portraits to bold, expressive splashed‑ink landscapes. Skill, combined with his enormous passion and energy, led him to turn out an average of 500 paintings each year. While he developed his own unique style through a multitude of influences, he insisted that his art remained firmly rooted in Chinese tradition.

Zhang moved to Macao in 1949, where he lived and worked for a period; he left China the same year. He went on to live in Argentina, Brazil, and Carmel, California, before settling in Taipei in 1978. He built impressive homes for himself with Chinese classical gardens, a small reminder of home.

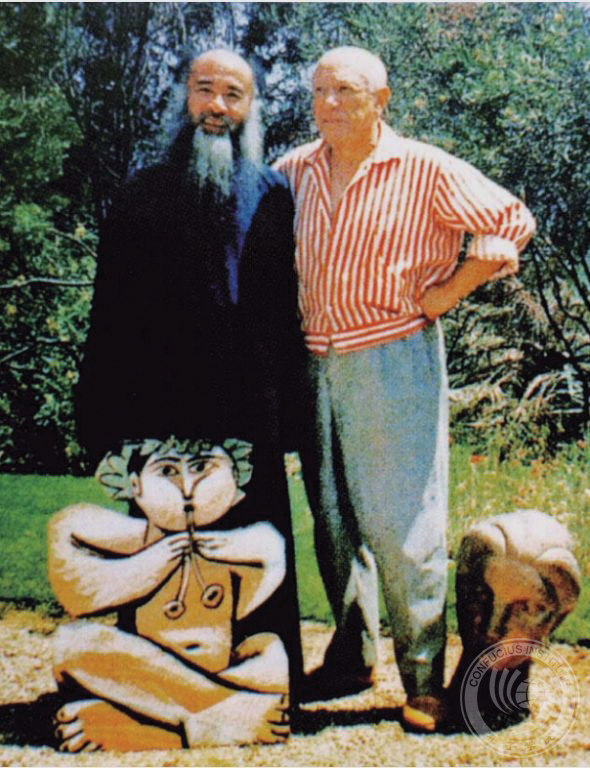

While in France in 1956, Zhang met with Pablo Picasso, an event broadly viewed as a summit between the masters of Eastern and Western art. The two men exchanged paintings. When Picasso showed Zhang drawings he had done in the “Chinese style”, Zhang commented that he had not used the right tools.

A gregarious person, Zhang spent much of his time in the company of a large entourage of family, students, friends, and admirers. He also mastered guanxi – the cultivation of a network of mutually beneficial relationships – often gifting his pieces to influential people, and to teachers, doctors, and chefs who provided him with help and services. He received gifts, as well. Many of his personal seals, for example, were produced for Zhang by friends. His affable nature, along with extensive travel, enabled Zhang to develop a wide circle of acquaintances and maintain deep friendships throughout his long life.

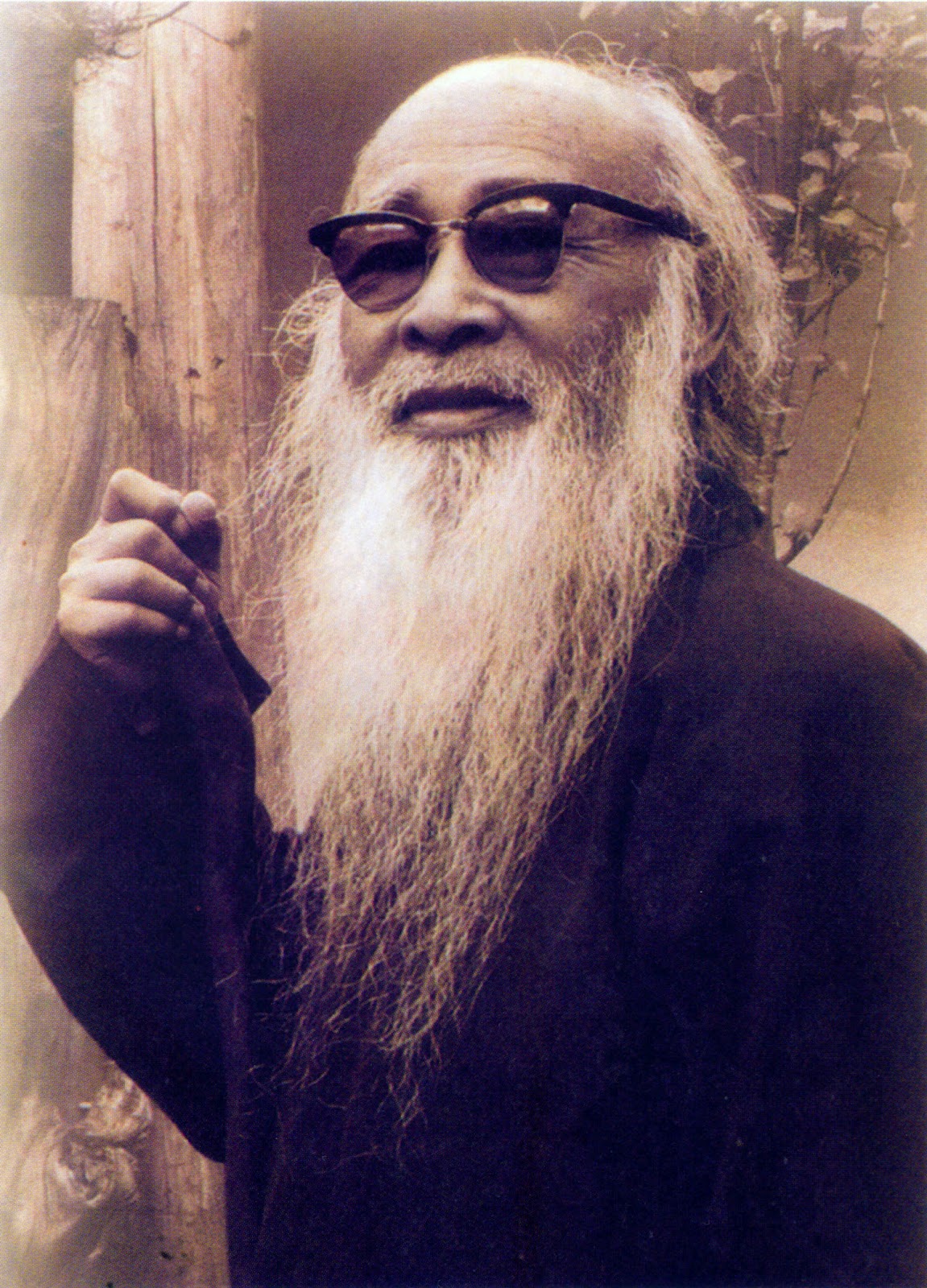

Zhang transposed the image of a traditional Chinese artist and literary figure, sporting a flowing beard and the long robes of a scholar. An appropriate choice for a man considered one of the most learned Chinese artists of the 20th century. His virtuosity and knowledge of different styles also made him one of the century’s most gifted master forgers. Zhang took pleasure in revealing that an “ancient treasure” in a famous collection was actually a copy he had made. Several major American art museums have purchased his copies as originals, leading curators to assess the authenticity of Chinese paintings – particularly those from the bird and flower genre – with Zhang in mind. His own works have become precious, and so popular, that they are often forged.

The real thing can be expensive. In April 2016, Sotheby’s in Hong Kong auctioned Peach Blossom Spring, a large hanging scroll painted the year before Zhang’s death in 1983. The important late‑career work sparked a fierce bidding war, drawing more than 100 bids from the floor and via telephone. It sold for US$34.7 million (MOP279.2 million), including buyer’s premium. The record‑setting sale helped make Zhang the highest‑grossing artist at auction in 2016, surpassing his old friend, Picasso.

Ascending to new heights

The MAM exhibition offers the public an opportunity to experience the incredible range and evolution of Zhang’s work. Leung Hio Ming, president of the Cultural Affairs Bureau, explains that the aim of the exhibitions of the MAM is to introduce and promote the works of great Chinese and foreign artists, highlighting their historical importance.

His painting skills and sensitivity transcended the frame of traditional art. Even in his twilight years, he showed no signs of diminished ambition but scaled new heights of virtuosity

Leung Hio Ming

“The Art of Zhang Daqian, co‑organised with the Sichuan Museum, beautifully serves this very purpose. Assiduously devoted to the study of traditional art forms throughout his life, Zhang mastered the strengths of many different great painters. He was equally accomplished in meticulous brushwork, freehand brushwork, depiction of flowers, birds, and landscapes, as well as figure painting” says Leung Hio Ming.

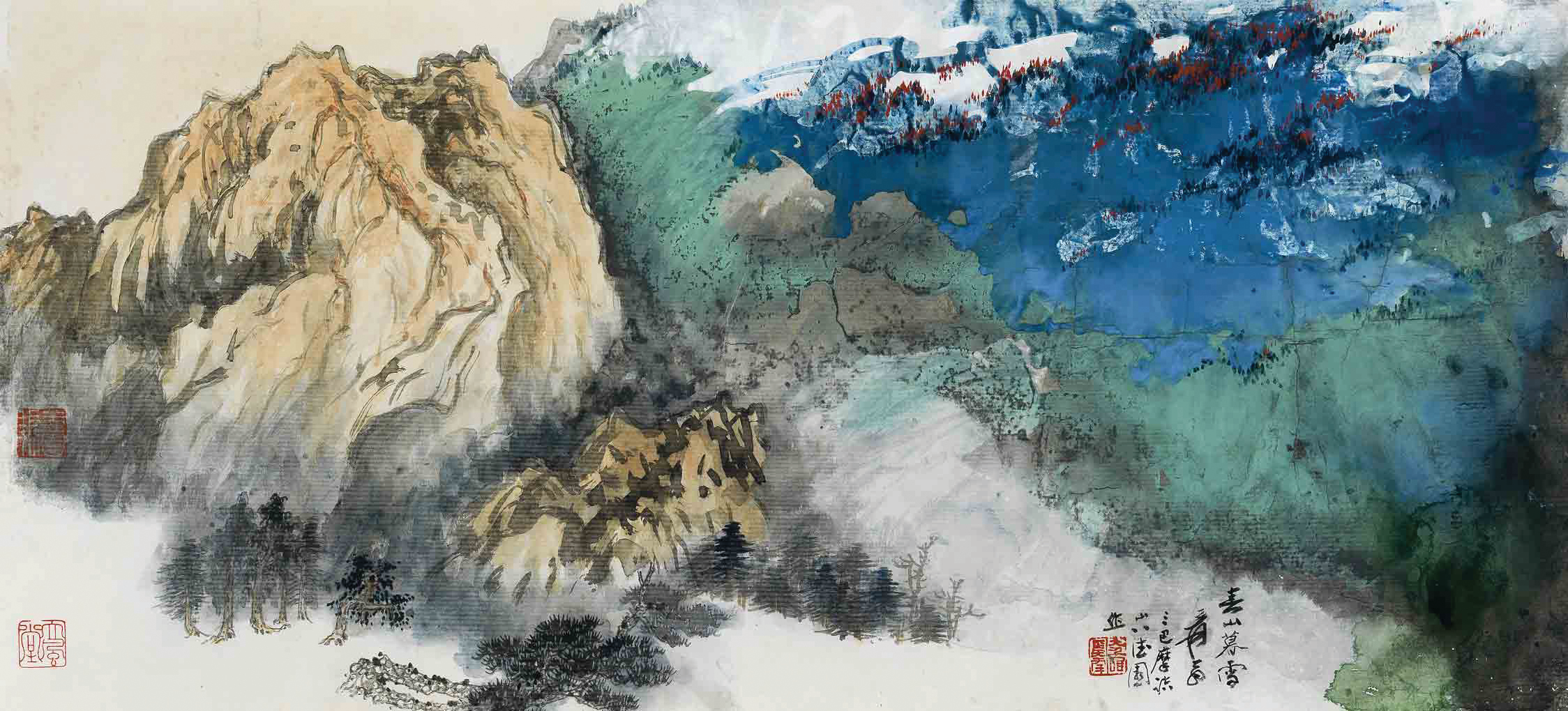

Leung points to the two years Zhang spent in Dunhuang as pivotal in his work. “After Dunhuang, his painting skills and sensitivity transcended the frame of traditional art. Even in his twilight years, he showed no signs of diminished ambition but scaled new heights of virtuosity. He perfected the splashed‑ink style, and created the splashed‑colour style by infusing traditional painting style and colour applications with elements of Western abstract art.”

The exhibition illustrates this transformation, including work produced before and after his time in Dunhuang, as well as the mural replicas themselves. “The precise, detailed copies of murals are evidence that Zhang held traditional culture in high esteem. They express his passionate love of nature and life through the vastness and multiplicity of creation depicted in his landscape paintings,” says Leung. He expresses his gratitude to the Sichuan Museum for loaning the collection.

Son of Sichuan

According to Xie Zhicheng, deputy director of the Sichuan Museum, Zhang remained intensely nostalgic for his native Sichuan throughout his life. “The Sichuan Museum houses an extensive, elaborate collection of Zhang’s works, all of which were donated by his family members,” says Xie.

During his time in Dunhuang, Zhang carefully studied the murals in the caves, producing 309 copies. “These copies have fascinated the art world with their grandeur and beauty,” says Xie. “He successfully departed from a painting style marked by a continuum of traditional techniques and sensibilities, to one with a confluence of the influences he gathered.”

“Zhang’s innovative technique is a great contribution to the progressive development of Chinese painting and art,” Leung Hio Ming adds. “The landscape paintings Zhang did during his later years, largely in subtle grades of splashed ink, blue and green tones, are spectacular vistas of rolling mountains and soaring pines enveloped in a hazy, mist‑shrouded surrounding, in which the silhouette of human figures is faintly visible. Their intrinsic composition, blurring the lines between fantasy and reality, convey infinite thoughts and feelings for those who see them.”

Through 100 pieces “of exquisitely refined quality that epitomise his masterly command of techniques and materials,” Xie says, “The Art of Daqian offers visitors an intimate perspective of the extraordinary world of the master painter.”