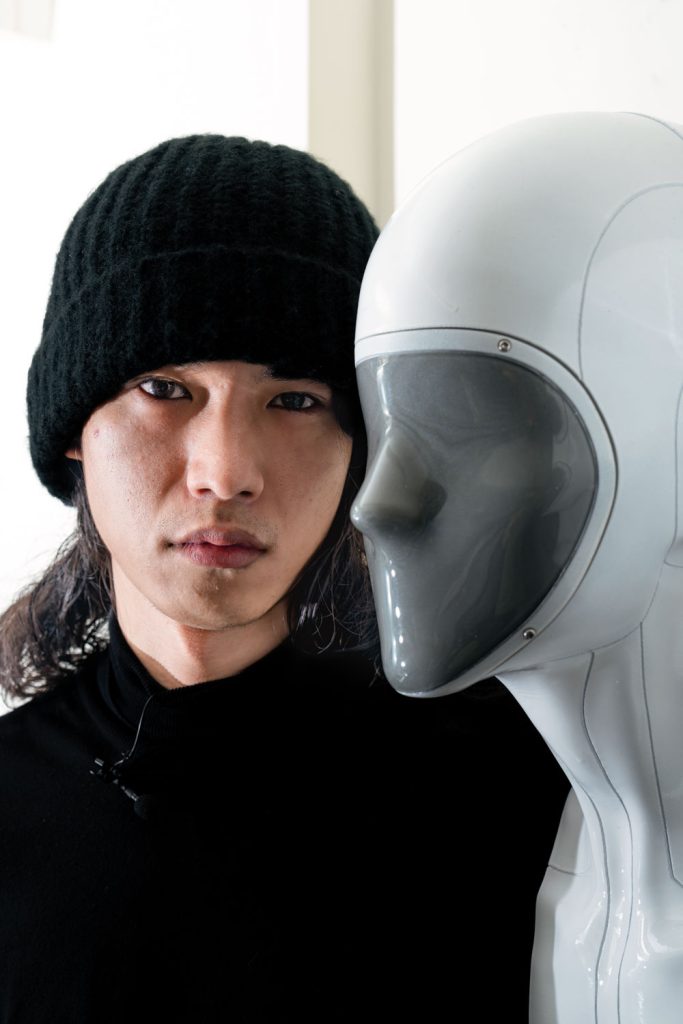

In 2021, an emerging artist named Wong Weng Cheong held a solo exhibition at Macao’s Casa Garden. Titled “Somewhere Still Wild”, images of dimly lit grasslands dotted with stretched sheep occupied the walls. Wong’s work had an ethereal quality; a mesmerising creepiness. The show caught the attention of Chang Chan, an independent curator who divides her time between Macao and London. She immediately knew its Macao-born artist was someone she wanted to work with. “Cheong is not a very expressive person, but his works are deeply moving,” she told Macao magazine. The curator describes his artwork as having “an intense style of its own”. One that’s a little grim and post-apocalyptic, but arresting.

“Somewhere Still Wild” led to the pair’s collaboration on Wong’s next exhibition, “The Secret of the Golden Flower” (an examination of humanity in the age of artificial intelligence). Last year, “The Secret of the Golden Flower” was selected for Macao’s International Art Biennale. This year, Wong and Chang have set their sights even higher: they’re off to the Venice Art Biennale, which opens this month. The Macao-born artist was selected to represent Macao by a panel of five arts academics and professionals.

Finding his own style

Wong’s passion for art started in high school, where he spent much of his time sketching portraits. “I did that without really thinking about creating a distinct style,” the 30-year-old says. In 2012, at the age of just 18, his work featured in the inaugural Macao Printmaking Triennial.

After that introduction to art as a profession, Wong earned a scholarship from the Cultural Affairs Bureau to study at the prestigious art college Goldsmiths, in London. Steeped in history and home to some of the best art institutions in the world, his time in the UK had a profound impact on Wong. Its distinctive scenery and landscapes – sheep grazing windswept pastures, the flitting shadows of clouds – are often visible in his oeuvre.

Spindly legged sheep, in particular, have become a recurring motif. He sees the woolly ruminants as indifferent to what’s going on around them, focused only on eating. “In my work, the more a sheep eats, the longer its legs grow until, finally, it won’t be able to reach down to the grass,” Wong says. These sheep find themselves in what Wong describes as a contradictory situation: longing to devour even more grass, but prevented from doing so by their own insatiable appetites. He explains the concept as illustrating the perils of unchecked consumerism.

Searching for connection

Wong’s installation for the Venice Biennale is titled “Above Zobeide”. ‘Zobeide’ is a reference to a fictional city in a novel by the Italian writer Italo Calvino, who wrote Invisible Cities in the early ’70s. The book is framed around a conversation between Marco Polo and the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan, where the former tells the latter about his experiences exploring the world.

According to Calvino’s Marco Polo, Zobeide is a chaotic, maze-like city full of men yearning for connection – yet amplifying their sense of isolation through an insistence on constructing their own, private spaces. The novel is a reflection on humanity’s search for meaningful relationships in a world where individualism reigns.

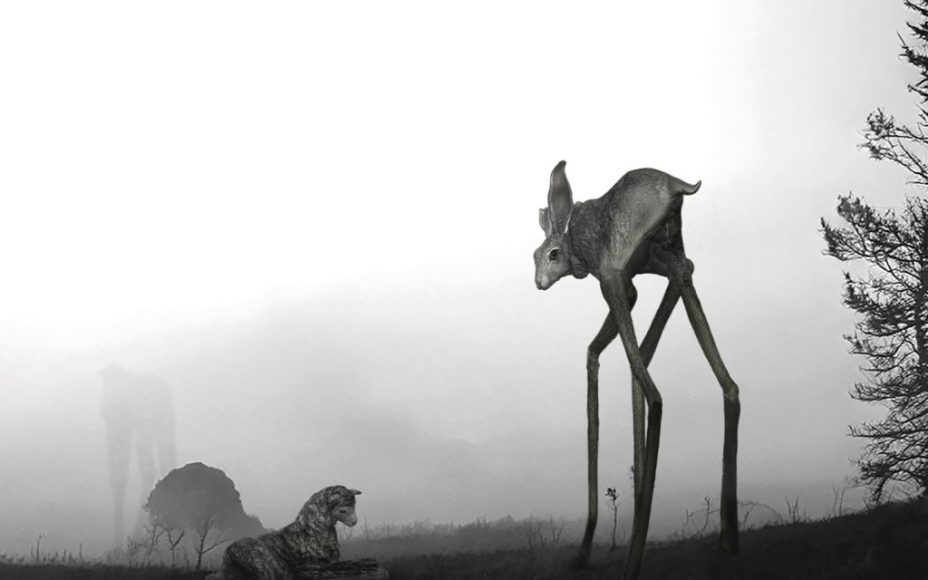

Wong’s work is a personal interpretation of Zobeide, however. In his version, the city takes on a preternatural undertone that hints at something having gone terribly awry. Spread across different rooms, the first inducts viewers into a pastoral scene that’s more bleak Wuthering Heights than William Blake’s green and pleasant land. The land is populated by 3D models of otherworldly animals (deer, hares and cattle this time, all with Wong’s signature spindly legs). While there’s also a wooden, apparently residential tower and lamp post, suggesting people live in this manufactured world, Wong’s installation is devoid of human life. The only people tentatively making their way through his eerie landscape are Biennale goers. Or, as the artist labels them, “invaders”.

In the next room, a sense of intrusion deepens. CCTV-esque cameras are recording what’s going on in the first, and in this room the footage of Wong’s invaders gets displayed on monitor screens for all to observe. The exhibition’s attendees thus become part of the installation.

The Macao Museum of Art (MAM) has been instrumental in pulling together “Above Zobeide” – a large and ambitious work – according to Chang and Wong. As it does with every Macao representative at the Venice Biennale, MAM organised the likes of shipping the installation to Italy and getting it set up in situ. The museum also helps promote Macao’s exhibits.

‘Foreigners everywhere’

The theme of this year’s Venice Biennale is “Foreigners Everywhere”. Each participating artist’s work must involve an interpretation of that theme. According to the biennale’s curator, Adriano Pedrosa, it has two possible meanings. The first is literal: in today’s globalised world, we encounter people from other countries wherever we go (and we are often the people from those other countries). The second meaning is more introspective: no matter where we are, we can’t shake the feeling that we’re different – an alien.

Both options resonated with Wong and Chang, who managed to pull together their biennale submission in just two weeks. Ultimately “we were more drawn to the second meaning,” Chang says. “And we found it interesting to explore the question of why we feel like foreigners. It has something to do with our personal experiences.”

Chang herself has long been a foreigner, of sorts. Born in Hubei Province in 1987, she relocated to Macao to study management in 2009. When she finished her degree, she realised she wanted to combine what she’d learned with her longtime passion: the arts. To do that, Chang pursued her masters in arts and cultural management at King’s College, London. There, she became a foreigner for the second time.

Wong, of course, also experienced life as an expatriate while living in the UK. But his sensation of always being on the outside stems more from a deeply introverted personality. “He always wants to be alone, but his dream life of living without others is impossible in reality,” explains Chang. Such feelings are part of the reason why much of Wong’s artwork involves landscapes lacking people. And drew him to Calvino’s story about Zobeide.

Wong’s installation, however, also manages to align with Pedrosa’s first definition of the ‘foreigners everywhere’ concept. That wherever you go, even this seemingly abandoned and somewhat eerie landscape, you can’t escape other people.

The Venice Biennale was founded in 1895 and is the oldest arts event of its kind. The festival spans much of the year, kicking off in April and running until November. “We feel very grateful to be able to participate in such a global event,” says Chang, speaking for both herself and Wong. “We can promote Macao art and learn by exchanging ideas with our global counterparts.”