In 1844, on 15 August, an ambassador from France arrived in Macao to advance negotiations for the Treaty of Whampoa. Théodose de Lagrené settled in the city with his wife, two daughters, and almost a hundred diplomats, secretaries, delegates and naval officers. They, in turn, were accompanied by scores of staff, including French cooks and sommeliers.

Just two months later, the treaty was signed by the Qing dynasty of China and the Kingdom of France – aboard the warship Archimède. It ushered French commerce into southern China and secured Macao as France’s distribution hub. While Lagrené set sail back to Paris in January 1846, many from his mission stayed longer. Their three years in what was then a Portuguese-administered city left a substantial library about 19th-century Macao, in the forms of travel books and newspaper articles.

It was one of these articles, written by the Frenchman in charge of Chinese silk exports, that first described Macao as “cosmopolitan”. Isidore Hedde explained that the city was home to thousands of people from “all races on earth”, including the Portuguese, English, Spaniards, Italians, dozens of French missionaries, many Northern Europeans, black Africans, Zoroastrians from India, and people from what are now Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia. Hedde’s “Lettre de Macao” appeared in the then-popular Parisian newspaper Journal des débats on 28 July 1845. This paper, incidentally, published 558 articles about Macao between 1816 and 1900 – a volume unparalleled by any other European newspaper at the time.

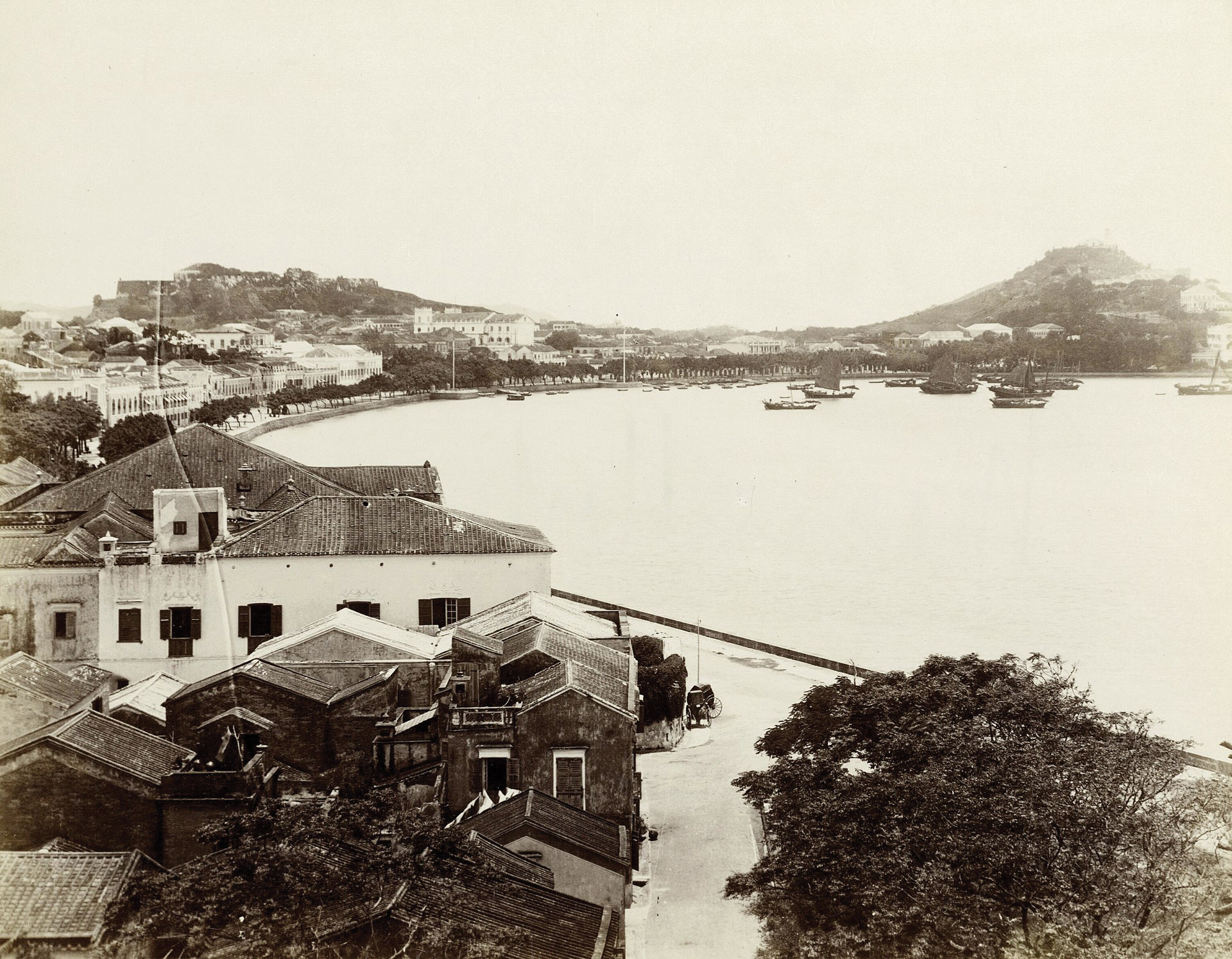

“Cosmopolitan” became a go-to description for Macao throughout the late 19th century. People wrote about the great Chinese bazaar where foreigners could buy anything, from exquisite lacquered furniture to pet monkeys, and noted Macao’s more than two dozen gambling houses. According to memoirists at the time, hundreds of Chinese and dozens of foreigners flocked to these every night to play fantan (where players cast bets on values of 1 through 4). They described wealthy Europeans’ beautiful villas in Praia Grande Bay, endless musical and poetry soirées, exotic cuisines, and the constant movement of people and boats.

Cultural exchange and artistic inspiration

Macao’s cosmopolitanism developed gradually between 1780 and 1850. The British East India Company (1600-1874) and the Dutch Oriental Company opened offices and leased residencies in the 1760s; Sweden, Denmark, the Austrian Netherlands and the Genoese Republic followed suit within the decade. The first French consul arrived in 1784, followed by Spain’s Royal Company of the Philippines, which set up shop on Rua de Santo António. Behind these national representatives came private entrepreneurs and adventurers. The Dutch distributed the first newspaper published in the Far East, the short-lived Batavaise Nouvelles, in Macao from 1744. The Spanish brought over Del Superior Governo, the first newspaper published in the Philippines from 1811.

While trade brought people from all over the world to Macao, a steady stream of festivity brought them together. Macao already celebrated traditional Chinese festivals, such as Lunar New Year and the Dragon Boat Festival. Powerful compradores (local agents working as intermediaries for foreign traders, who arrived in great ships) added Cantonese theatre and opera to the mix, arranging for troupes to perform along the island-hopping trade route to seasonal Canton trade fairs. Stops included Macao, Lapa island (now the Wanzai peninsula), and Whampoa island (now Pazhou island, part of downtown Guangzhou).

Two French memoirs, written by the naval officer Marie-Jules Dupré and a young diplomat named Charles-Hubert Lavollée, recall one of these spectacles in 1845. A four-hour-long Cantonese opera apparently left its foreign audience (including Englishmen, French, Dutch, Swedes and Italians) thoroughly impressed. Another memoir recalls a show in 1888, held at Macao’s Senado Square, that lured French and English tourists over from Hong Kong especially to see it.

Meanwhile, the Europeans competed with each other to impress Macao’s Portuguese government, mandarins, and Chinese merchants. The English built a library and a natural history museum, and hosted lively snooker tournaments at their headquarters in Praia Grande Bay. The Spanish threw regular flamenco parties. All the Europeans enthusiastically celebrated their respective national days, newly arrived countrymen, their subsequent departures, and any commercial success. In 1823, the Ostend Company (from the Austrian Netherlands) hosted a musical soirée where two German singers performed arias from Mozart’s The Magic Flute. The Genoese responded in 1825, shipping opera singers over from Milan to perform Rossini’s The Barber of Seville.

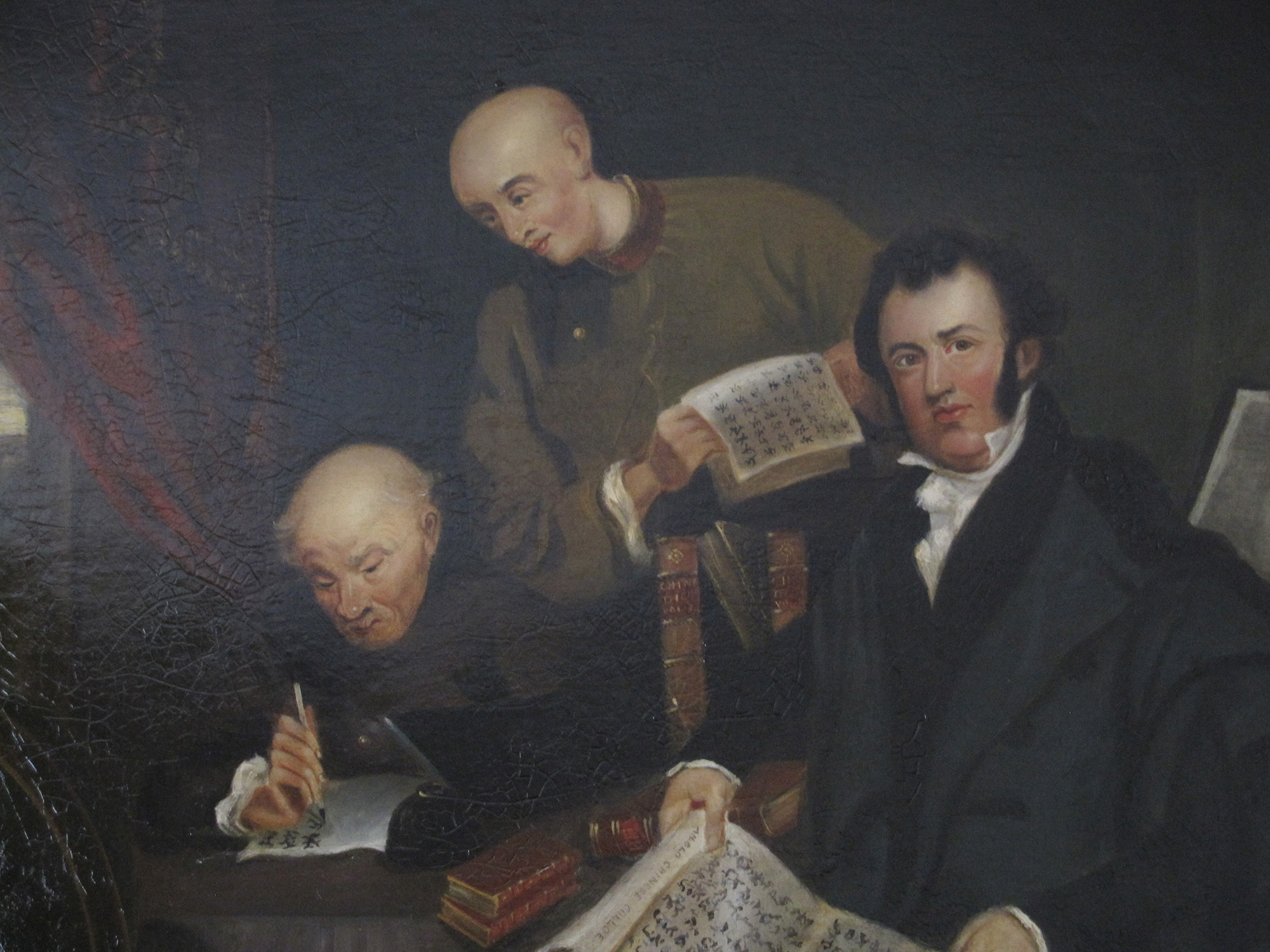

Several well-known European painters also spent time in Macao, finding inspiration in its landscapes and people. The English artist George Chinnery was based here from 1825 until his death in 1852, and befriended the celebrated French painter Auguste Borget, who had a studio at the rich opium and coolies trader Jean-Antoine Durand’s large house in Praia Grande Bay. Chinnery also mentored the Anglo-Indian painter William Prinsep, whose father worked for England’s East India company. These artists’ work helps reveal what Macao in the 1800s looked like.

Hedonistic homes and holidays

In those days, private parties held by Macao’s resident Europeans were known to be decadent. Prosperous Portuguese opium traders, such as Commander Manuel Pereira, Januário Agostinho de Almeida and Francisco José de Paiva, invited high-level officials and visitors to lavish dinner parties and out on hunting expeditions. These convivial occasions could include a servant per guest, along with the finest French cognac and cigars from Manilla. Lavish soirées were also held by Swedish Anders Ljungstedt, an amateur historian and private trader, and by Magdalenus Jacobus Senn van Basel, who represented the Dutch diplomatic interests in Macao until 1848.

One famously hospitable opium trader (also the honorary consul to Prussia) was the Scotsman Thomas Beale. He owned an enormous aviary filled with hundreds of rare birds, including a flamboyantly coloured bird-of-paradise that was allegedly tame enough to feed from Beale’s hand. The Scotsman worked with local Chinese animal peddlers to supply well-heeled foreigners with exotic pets: Siamese cats, Pekingese dogs, and a Sumatran monkey for the wife of Lagrené, the French ambassador. In 1856, the French novelist Léon Gozlan published a book partly inspired by Beale titled The Man Among the Monkeys; or, Ninety Days in Apeland.

Lagrené’s successor, Charles Lefebvre de Bécourt, taught Macao how to celebrate Bastille Day with the finest champagne, French wines and liqueurs; then Lefebvre de Bécourt’s successor, Baron Alexandre Forth-Rouen, added fireworks. Not to be outdone by the French, a consul of the United States brought a famous singer over from San Francisco for America’s Independence Day celebrations in 1852. She toured Macao’s wealthiest homes to much applause and some scandal due to her skimpy dress. That consul, Frederick Busch, explained in his memoirs that diplomats preferred the freedoms of Portuguese Macao to stuffier British Hong Kong.

Britain’s occupation of Hong Kong, which began in 1841, was not a direct cause of Macao’s eventual decline as an international trade hub – at least, not initially. In fact, the 1849 edition of the Manual of China’s Export Trade described the new Hong Kong market as a boon for Macao’s businesses. The occupation increased trade, investment, and visitors to the city, as well as expanding job opportunities for people based in Macao, who could hop across to the fast-developing neighbouring island. The Manual said foreign traders and wealthy families continued to prefer Macao for its many luxury Chinese goods, including silk and rice paper paintings.

Indeed, Macao became a fashionable holiday destination for Hong Kong-based colonial officials. Back then, it was considered fresher, healthier and more generally pleasant than the British-administered city. There was plenty of gambling (even in those days) and shopping to be had, plus the so-called sim-sungs (tea houses with music and opium) at the bazaar.

Macao was also popular with the colonialists in what was then French Indochina. In a 1887 memoir, the city’s first French-language tour guide – Claudius Madrolle – was yet another person to describe it as “very cosmopolitan”.

The French doctor accompanying Lagrené’s mission in the 1840s, Melchior-Honoré Yvan, wrote that Macao possessed “salons where you can talk or discuss, like in London or Paris, where the women are elegant, and the men are very polite.” Yvan prided himself on befriending the Chinese peasants of Mong Ha as well as highly prosperous Portuguese traders, and his voluminous 1853 travel book recalled Macao as a uniquely transcultural destination. In it, he praises a “very active young lady” – presumably Macanese – who read Homer and Virgil in Latin, and noted that there were plenty of others like her. “Cosmopolitan women [in Macao] speak several languages and eagerly seek out literary news printed in London, Paris, Lisbon, Madrid, or Calcutta,” Yvan continued. “Does the reader know many French ladies who can boast of such philological knowledge?” Many 19th-century travellers to Macao echoed his sentiments in their own writing.

The people writing about Macao at that time tended to view it from positions of immense wealth and privilege; their observations must be viewed through that lens. But there is no doubt that 19th-century Macao was a hotbed of cosmopolitan decadence. While fallen empires, land reclamation and technological progress are just some reasons why a time-travelling Lagrené or Beale might fail to recognise modern Macao, architectural glimpses of their world remain today and are part of the city’s cultural heritage.