TEXT: Cláudia Aranda

Macao has just marked the 15th anniversary of the inscription of its Historic Centre on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. The government, as well as many citizens, have worked tirelessly to protect the city’s historic heritage but there’s still plenty to do over the coming years.

On 15 July 2005, Macao received one of the biggest boosts it could ever get to its status as a regional tourism hub. On that day, the Historic Centre of Macao was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List – a list reserved for some of the globe’s most important sites of cultural, historical or scientific significance. It was a day of celebration, marking the Macao government’s tireless work in preserving and promoting a site that not only includes fascinating old buildings and monuments like the Ruins of St Paul’s, the A-Ma Temple and Mount Fortress but also attracts millions of tourists to the city every year.

Fifteen years on and the government – along with the people in Macao – has just celebrated an important milestone with a series of activities throughout July and the beginning of August, conveying the concept of ‘Appreciating Our World Heritage Together’. The 15th anniversary of the inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage List was marked by a weekend event called the World Heritage Open Day, as well as a WeChat game, for the public to appreciate the Historic Centre of Macao. Residents from across the city flocked to the World Heritage Youth Education Base, located in the Mandarin’s House and Lilau Square, to take part in history-related activities, thematic exhibitions and special workshops, as well as to watch song and dance performances and buy cultural products. Last month, the celebrations continued with the ‘Heritage City Tours – Guided Tours and Illustration Workshop’, which were held across a number of days and featured walks around World Heritage buildings led by professional guides with plenty of stories to tell.

The celebrations weren’t just about re-emphasising the importance of the UNESCO listing after 15 years, though. They were another example of the Macao government’s successful work over the past decade-and-a-half to increase residents’ awareness of the value of the city’s cultural heritage and the importance of conserving it. This work has contributed to the establishment of local heritage advocacy and defence groups. In a way, the 2005 addition to UNESCO’s list was just the beginning. In a statement from the Cultural Affairs Bureau (IC) to Macao Magazine, an IC spokesperson says: “Macao people have become more aware of and concerned about the cultural heritage around them through publicity, education and promotion over the years, and their awareness of cultural heritage conservation has been raising gradually as well.”

Centre of it all

The Historic Centre of Macao is home to more than 20 buildings, monuments and sites. In 2005, UNESCO described the centre, ‘with its historic street, residential, religious and public Portuguese and Chinese buildings’, as providing ‘a unique testimony to the meeting of aesthetic, cultural, architectural and technological influences from the East and West’. It became, at the time, the 31st UNESCO World Heritage site in China.

The Ruins of St Paul’s, pictured here at dusk, is at the heart of the Historic Centre of Macao; the A-Ma Temple; the Holy House of Mercy; St Augustine’s Square | Photos by Sean Hsu; António Leong; Jack Hong

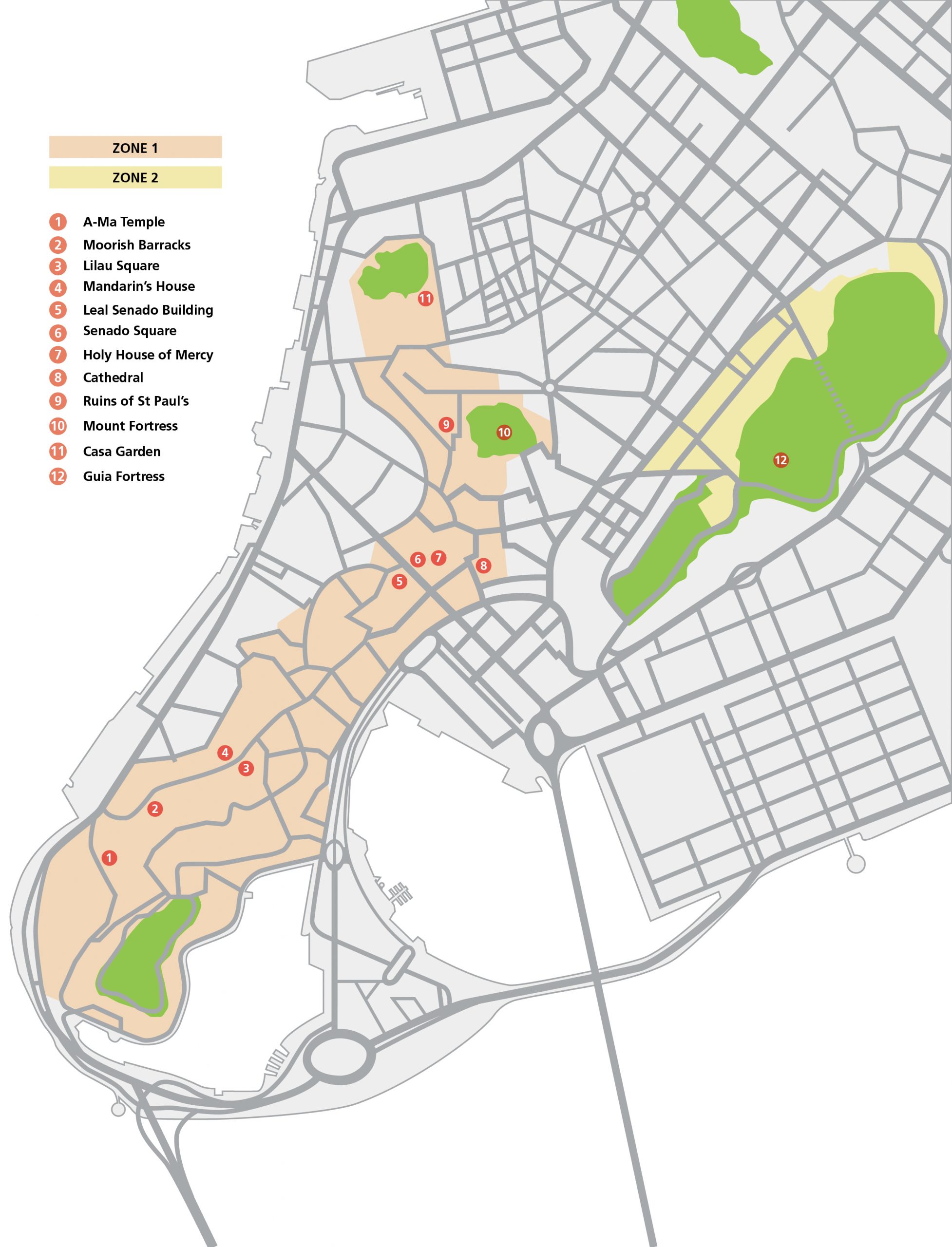

UNESCO, back in 2005, described Macao as ‘a lucrative port of strategic importance in the development of international trade in [the] Chinese territory’. It was a Portuguese trading post from 1557 and it then became a Portuguese city, staying that way until 1999, when its administration was transferred to China. The historic centre was formed over all these years and now, as outlined under the World Heritage listing, it comprises two distinct areas. There’s Zone 1, which contains sites between Mount Hill and Barra Hill, and there’s Zone 2, which refers to the heritage venues on Guia Hill. Aside from the likes of the A-Ma Temple and the Ruins of St Paul’s, it also contains historical gems like Senado Square, St Augustine’s Square, the Holy House of Mercy, the Lou Kou Mansion and Guia Fortress, which includes Guia Chapel as well as the famous Guia Lighthouse. Even a section of the old city walls is included.

When describing the Historic Centre of Macao’s ‘outstanding universal value’, UNESCO refers to the different nationalities that settled in the city, along with the missionaries ‘who brought with them religious and cultural influences, as illustrated by the introduction of foreign building types’ like China’s first Western-style theatre, Dom Pedro V, as well as the city’s churches and fortresses, many of which are still in use. UNESCO also highlights that ‘Macao’s unique multicultural identity can be read in the dynamic presence of Western and Chinese architectural heritage standing side by side in the city’ and ‘the same dynamics often exist in individual building designs, adapting Chinese design features in Western-style buildings and vice-versa’. An example of this is the incorporation of Chinese characters as decorative ornaments on the Ruins of St Paul’s Mannerist church façade.

The Macao Government Tourism Office (MGTO) has been using the fact that the historic centre is on the UNESCO World Heritage list for 15 years to raise awareness internationally and to successfully attract tourists to the city. “The Historic Centre of Macao,” says the IC statement, “constitutes a unique urban landscape of Macao, creating a distinctive urban personality that attracts tourists from all over the world every year.” The statement adds that this landscape serves ‘as an essential foundation for Macao to build itself as a destination for international leisure and tourism’.

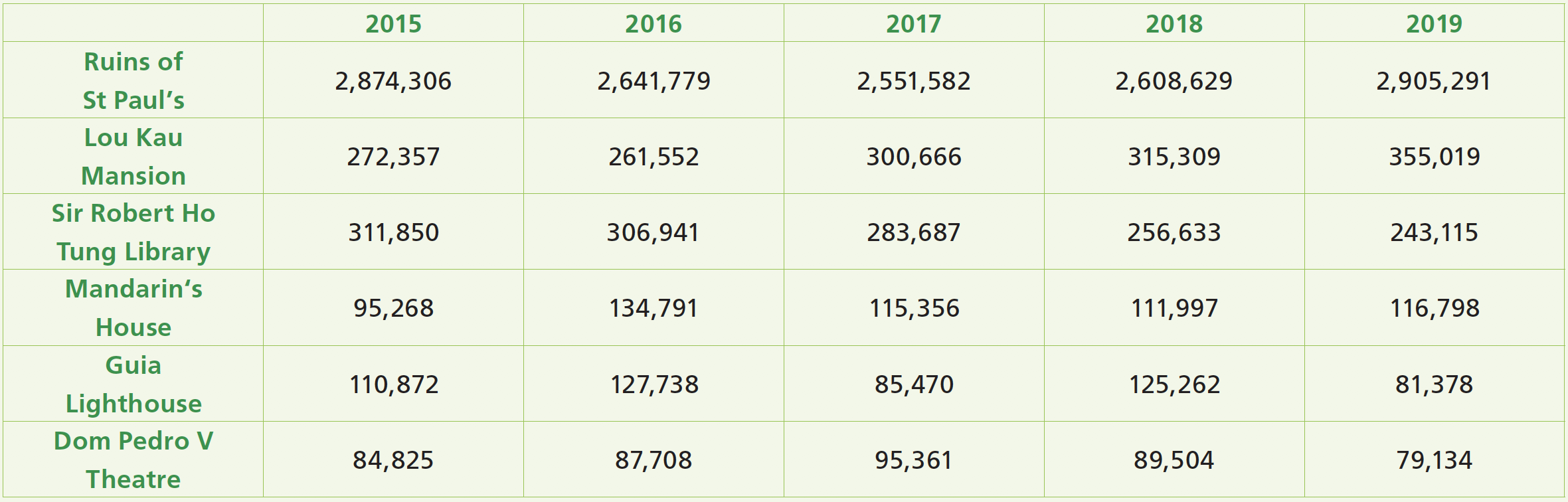

Based on the findings of several visitor profile studies conducted by MGTO over the past five years, the Ruins of St Paul’s ranks as the most popular attraction for tourists. Last year, more than 2.9 million visitors travelled to the iconic site, according to the IC. “Indeed,” says the statement, “the signature façade can be considered as the landmark of Macao and a must-visit spot for tourists and residents alike.”

“We are proud of such heritage,” says Chan Tak Seng, one of the founders of the Concern Group for the Protection of the Guia Lighthouse, “and we should preserve such heritage for our next generations.” Chan, who is also a former member of the Urban Planning Committee (CPU), says the Historic Centre of Macao is a ‘unique testimony to the encounter between East and West, in particular between China and Portugal’, and he highlights the Guia Lighthouse as ‘an important monument’ that demonstrates ‘the prominence of Macao in the international trade’ at the time it was built, which was around 1865.

Last month, Macao officially became a member city of the Organisation of World Heritage Cities, an international non-governmental organisation that gathers around 250 cities with UNESCO World Heritage sites together. This means the city can have access to more international information on World Heritage preservation and can participate with the organisation in relevant events.

River relationship

Architect Maria José de Freitas, who is the CEO at AETEC-Mo Architecture and Engineering in Macao – and a member of the International Scientific Committee of Shared Built Heritage (ICS-SBH) part of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) network of experts – notes that the great value of Macao is that it’s a ‘port city that was developed in a relationship with the river estuary’. She says the Portuguese part of the city was, from the start, ‘built in parallel with the Chinese quarters’ allowing Macao to have ‘its own characteristics’, revealing a culture ‘that’s very genuine and very authentic’. It is this ‘cultural mix and this hybridism’, she says, ‘that is translated into the architecture and the urbanism that made Macao noticed and evaluated by UNESCO’. “Macao’s [nearly] five centuries of history of multiculturalism, interrelation and communion,” she says, “makes the city distinctive in the Pearl River Delta.” De Freitas says that these multicultural values are now ‘more important than ever’, creating ‘Macao’s added value within the Greater Bay Area’. She notes that the ‘city could set an example’ as a multicultural place and in the way it deals with its heritage.

Agnes Lam Iok Fong, legislator and the director of the Centre for Macau Studies at the University of Macau – which offers a ‘philosophy in Macao studies’ master’s degree that includes a component on the historical heritage of the city – stresses that this historical heritage is definitely a part of the SAR’s identity. “It is this aspect that makes Macao different from any other city,” she says. “This makes it unique and allows the locals to understand that this is not just a casino city but a city with a deep history and culture.”

The importance of Macao’s heritage to the city’s identity is also ‘decisive’ for journalist and Macao history researcher João Guedes. “This is because,” he says, “it aggregates the Chinese and Portuguese dimensions. The former is overwhelming in its size and breadth. The latter is as small as it is vital to ensure that same identity. This marriage of convenience, which essentially defines the nearly 500 years of Macao’s history, inevitably results, in my view, in a city which is either unique or has few parallels across the world.” Guedes attempts to compare other places of miscegenation between East and West cultures, such as Goa or Malacca, with Macao. But he notes that ‘those antique places only preserve monumental remnants which are partially missing the cement of a truly present and living culture to complete their character’. He concludes that Macao has this ‘truly present and living culture’.

Guedes recognises the relevance of all the sites and monuments on the World Heritage list in Macao. However, the researcher highlights the Guia Lighthouse as having a special significance. “Not so much for its apparent usefulness,” he notes, “which was to guide vessels to a good port, but mainly because it stands as an indelible mark of the unique scientific and cultural development that Macao experienced in the last three decades of the 19th century.” Macao did indeed grow culturally and scientifically between 1870 and 1900. Guedes cites the construction of the Conde S Januário Hospital, built in 1874 and still open now, as being constructed ‘in an entirely modern mould for the time’. He adds that that period also saw ‘the advent of scientists and men of letters’ in Macao – like Portuguese writer Wenceslau de Morais and Portuguese symbolist poet Camilo Pessanha – as well as ‘the beginning of the engineering intervention in the Inner Harbour’.

Development vs heritage

Over the past 15 years, Macao’s government has adopted, according to the IC statement, ‘strict conservation measures to preserve and perpetuate the integrity of the Historic Centre of Macao’. But despite this, some experts say that one of the main threats to the city’s listed legacy has been the sheer amount of developments which have rapidly sprouted up, including housing projects like high-rises. Maria José de Freitas uses Guia Lighthouse as an example, saying its ‘visual integrity started to be disturbed’ when nearby high-rise constructions were being built. She adds these high-rises ‘started to cause a change in the skyline that came to disturb the viewing angles from the lighthouse’.

As a result of this pressure from developments such as new gaming establishments, housing areas and transport links, groups of concerned citizens have appeared over the past 20 years with the purpose of defending the city’s historic heritage, such as the Guia Lighthouse group and the Association for Macau Historical and Cultural Heritage Protection. De Freitas highlights the importance of a greater awareness of the city’s heritage in the public domain which has led to the formation of these groups and she notes the relevance of organisations like the Macao Heritage Ambassadors Association, a non-profit group created by young people in the city that promotes education on the SAR’s cultural heritage.

We are proud of our historic heritage in Macao. We should preserve such heritage for our future generations.

De Freitas also highlights the work of the Concern Group for the Protection of the Guia Lighthouse, which was created in 2007 to alert people, authorities and even UNESCO to development projects involving high-rise buildings in the area. It was argued that the projects would affect the historic centre’s visual integrity and would obscure the view of the lighthouse from the sea. In 2008, following input from UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee (WHC), the government, then under Chief Executive Edmund Ho, enacted an order that restricted building heights around the lighthouse area. It was a win for the concern group and it highlighted just how serious the city was when it came to preserving its tangible historic heritage. The concern group continues today.

Protecting the heritage

UNESCO’s WHC has, in the past, noted the efforts made by Macao’s government in building a legal system to strengthen the protection of the city’s historic centre, notably through the adoption of three laws in March 2014: the Cultural Heritage Protection Law, the Urban Planning Law and the Land Law. The protection of the Historic Centre of Macao will be further enhanced in the near future with the promulgation of the Safeguard and Management Plan of the Historic Centre of Macao – referred to as the ‘Management Plan’ – as stipulated by the Cultural Heritage Protection Law. This Management Plan, which is still in the preparation stage, will include action plans and regulations to protect visual corridors – designated areas which must not contain new buildings or obstructions to the view of the sky – in and around the heritage sites, including regulations to limit the height of any new buildings within the boundaries of the site and in the ‘buffer zones’ – areas around the site that have also been given an added layer of protection as developments there could also affect views – according to a ‘state of conservation’ report submitted by Macao to UNESCO in November 2018. In the same year, during the Management Plan public consultation, it was proposed to protect the existing 11 visual corridors.

Last year, the WHC highlighted that ‘there remain concerns about building height and various new developments that may have an impact on the outstanding universal value of the Historic Centre of Macao, including developments located outside the property and its buffer zone’. The WHC also remarked that the level of land reclamation that has occurred near the listed heritage also requires careful management to balance the opportunity that new urban areas provide to reduce pressure on historic areas. The WHC last year noted, however, the government progress that’s been made towards the development and completion of the comprehensive ‘Management Plan’ and its related regulations through a consultative process. It requires the submission of the plan to the WHC for review prior to its implementation. It also recommended the preparation of ‘Heritage Impacts Assessments’ to ensure that the potential impact of new developments, including their visual impacts, continue to be evaluated.

According to the statement by the IC, at the end of last year, the bureau ‘completed the compilation of the draft administrative regulations of the Management Plan and will continue to take forward the legislative work this year’. The IC spokesperson in the statement explains that to ensure the adequate protection and management of its World Heritage sites and to fulfil international commitments under the UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, it has been working on the Management Plan ‘in an orderly and phased manner’ since the Cultural Heritage Protection Law came into force in 2014. The IC says it completed two public consultations on ‘phases’ of the plan – its ‘framework’ and then its ‘content details’ – between 2014 and 2018. The IC statement says: “A total of 7,963 comments and suggestions were received in two public consultations, forging a broad social consensus for the Management Plan.” Furthermore, in both 2017 and last year, ‘additional immovable assets were officially listed as monuments and as sites of cultural and archaeological interest’ and the ‘establishment of the respective buffer zones was stipulated’.

Chan Tak Seng says that the city’s ‘Portuguese and Chinese heritage should be preserved, including the names of streets and places in Portuguese’. Agnes Lam believes that more attention should be paid to the 20th-century architecture in order to preserve it. “Buildings from the 1950s to the 1980s should start to be considered,” she says, “or we might lose that part of the city’s memory soon.”

Guedes believes that the existing list of heritage sites is already consistent but he also agrees with Lam. He says those who have worked to include historic heritage sites on lists of protection like the UNESCO World Heritage list ‘have done their homework’. It must be remembered, however,” he adds, “that what today is just a newly built site may always be a candidate in the future to be included in new heritage lists.”

The Historic Centre of Macao may have earned its inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2005 but who knows what other buildings could be added to the list and preserved in the city over the next 15 years? Only time will tell.

Building an identity

Initiatives over the past three years that have added to the UNESCO World Heritage list status in building Macao’s strong international identity.

- The ‘Official Records of Macao During the Qing Dynasty (1693-1886)’ – or ‘Chapas Sínicas’ – were added to the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in October 2017.

- Macao was then designated as a UNESCO Creative City of Gastronomy in November 2017, adding to the city’s already strong brand identity.

- Last year, the MGTO launched the ‘Guide for Travelling with Civic-Mindedness’, which offers tips and recommendations to tourists on sightseeing etiquette as well as raising their awareness on the concerted effort on heritage protection. The MGTO said ‘it is vital to protect and preserve the historical sites so that they will be able to carry on the story and continue to act as the presentation of Macao’s cultural identity for the long-term’.

- Also in June, 55 new items were included in the government’s ‘inventory of intangible cultural heritage’. There are now 70 items of intangible heritage – which means ‘untouchable’ heritage like beliefs and customs – including religious processions, Portuguese folk dancing (pictured above) and local foods like dragon’s beard candy.

- In August, Macao officially became a member city of the Organisation of World Heritage Cities, an international

- non-governmental organisation that gathers around 250 cities with UNESCO World Heritage sites together.

Special tourist attractions

How many people have visited these six World Heritage sites in Macao over the past five years and what makes them so special? Take a look…

The Ruins of St Paul’s: The ‘ruins’ are the façade of what was originally the Church of Mater Dei which was built between 1602 and 1640 and the ruins of St Paul’s College, which was once adjacent to the church. Both were destroyed by fire in 1835. The façade, which the IC says now ‘functions symbolically as an altar to the city’, is Mannerist in style with some distinctively oriental decorative motifs.

Lou Kau Mansion: The mansion is believed to have been built in 1889. It was the home of Lou Kau, a prominent Chinese merchant who owned several imposing properties in the city. The IC says the site ‘depicts the diverse social profile present’ in the centre of the ‘old Christian city’ where ‘this traditional Chinese residence stands near Senado Square and Cathedral Square’.

Mandarin‘s House: Built in 1881, this was the traditional Chinese residential compound home of prominent Chinese literary figure Zheng Guanying. This traditional Chinese residential complex illustrates, says the IC, ‘Macao’s multicultural background in this mix of architectural features and the building’s immediate and contrasting urban environment’.

Sir Robert Ho Tung Library: This three-storey building is, as the IC puts it, ‘a mansion in typical Macanese style’. It was constructed before 1894 and Hong Kong businessman Sir Robert Ho Tung purchased it in 1918. He died in 1955 and, in accordance with his will, the building was presented to Macao’s government for conversion into a public library.

Guia Lighthouse: Built in 1865, the IC calls this the ‘first modern lighthouse on the Chinese coast’. Macao takes its co-ordinates from the exact location of the lighthouse, which stands inside the Guia Fortress, itself built between 1622 and 1638. Also on the site is the Guia Chapel, which was built around 1622.

Dom Pedro V Theatre: Built in 1860 as the first Western-style theatre in China, the IC says that ‘this is today one of the most important cultural landmarks in the context of the local Macanese community and a venue for important public events and celebrations that remains in use to this day’. It is neoclassical in design.