TEXT Otávio Veras, Research Associate of the NTU-SBF Centre for African Studies; the centre is a trilateral platform for government, business, and academia to promote knowledge and expertise on Africa, and is established by the Nanyang University and the Singapore Business Federation. Otávio Veras can be reached at overas@ntu.edu.sg.

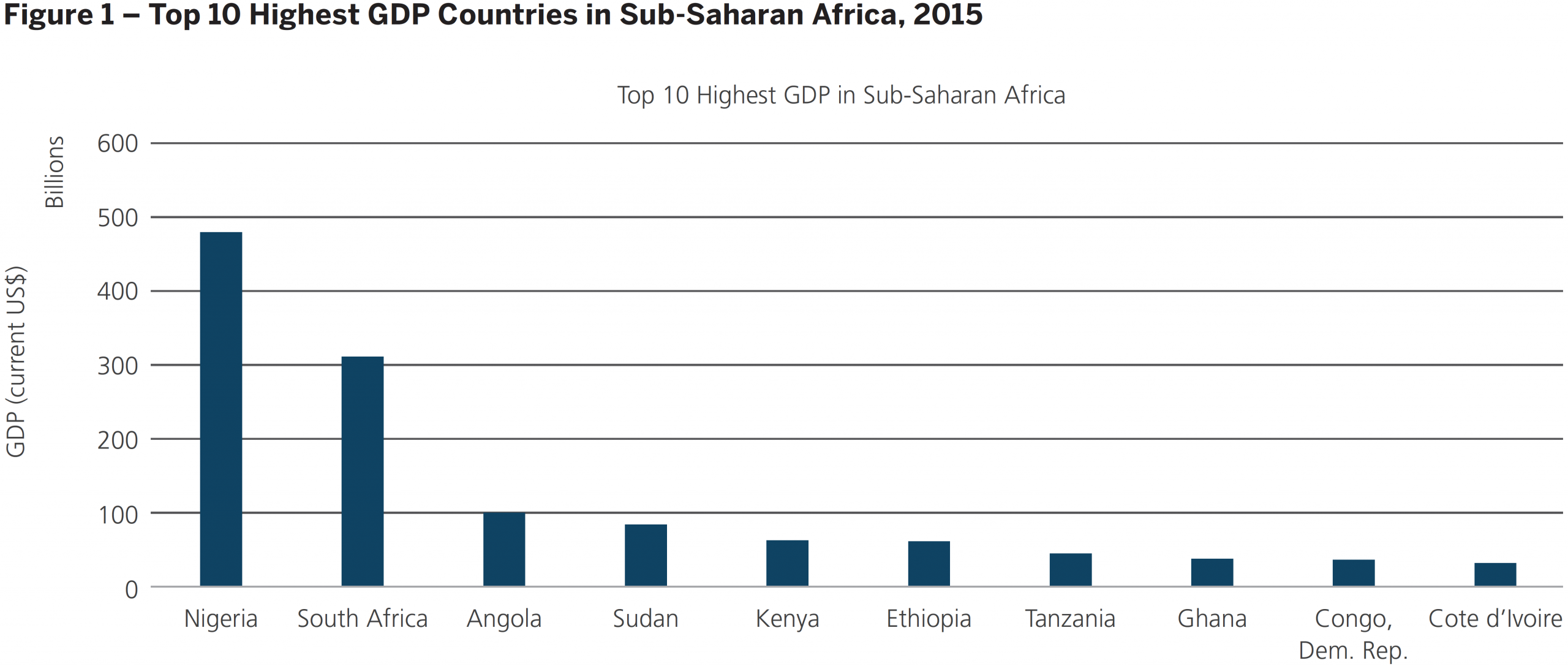

Angola has experienced rapid growth in the last decade, mostly propelled by the exploitation of its vast natural resources. Today, the country is ranked the third largest economy in Sub-Saharan Africa (see Figure 1). Its history, like that of many African nations, is characterised by conflict and war. After its independence from Portugal in 1975, Angola entered into a 27-year-long civil war with two major parties, the MPLA and Unita, fighting for supremacy. In 2002, the two finally agreed on a cease-fire and focused on rebuilding the country, thus commencing the rebirth of Angola.

Oil and Diamonds

Since 2002, Angola has relied primarily on its natural resources as its main source of revenue, catapulting the nation’s GDP to the third-highest in Sub-Saharan Africa. Oil constitutes most of the country’s GDP. The country is Africa’s second-largest oil producer, with a majority of its reserves concentrated in Cabinda province, a region with no borders with the rest of Angola plagued by a separatist conflict.

In recent years, oil production has increased exponentially, more than doubling from 800,000 barrels a day in 2001 to 1.8 million barrels a day in 2015. According to the Reuters article “Angola’s blooming banana plantations offer new hope for farming,” this resource is utterly indispensable to the nation: in 2014, oil exports alone accounted for an astounding 95 per cent of foreign exchange revenues, bringing in US$60.2 billion. This figure fell to US$33.4 billion in 2015, a 44.5 per cent decline as a result of the drop in the price of oil.

Diamonds account for a sizeable portion of revenue as well, although much smaller than that of oil. The region is Africa’s third largest diamond producer by quantity and value, surpassed only by Botswana, the world’s largest producer at roughly 38 million carats, and the Democratic Republic of Congo at 30 million carats. According to news agency Macauhub, Angola mined 10 million carats in diamonds in 2014, generating US$1.6 billion in revenue. The country’s production volume has oscillated annually between 9.7 and 8.3 million carats since 2006. According to Mining.com’s article Angola diamond industry to regain record production levels, “The new mining code introduced in 2011 attracted foreign investment and boosted exploration of the precious stone and other minerals.”

While these extensive natural resources have provided Angolans with rapid prosperity, it is also problematic in that the country’s revenue stream depends on commodities with finite quantities.

Investments in Angola’s oil industry have grown consistently over the past decade, dwarfing other sectors of the economy. During its colonial era, the country was a major exporter of coffee, sisal, sugar cane, banana and cotton and was self-sufficient in all food crops except wheat, according to the Global Agricultural Information Network. Civil war disrupted all agricultural production and displaced millions of people. The discovery of large, untapped oil reserves shifted the focus of the economy from agriculture to oil exploration, leading the country to cease investing in technology and the mechanisation of its agricultural sector.

The drastic decline in agricultural productivity coupled with seemingly endless revenue from oil has resulted in mass importation of food, which seems an easier solution than investing in domestic production to revitalise the dismantled agricultural industry. Once a net agricultural exporter in the 1970s, Angola now imports 90 per cent of its food at an annual cost of US$5 billion.

The sharp decline in commodity prices in recent years, especially that of crude oil, has severely strained Angola’s economy. Between 2010 and 2015, GDP grew at an average rate of 4.5 per cent. However, the country’s economy is projected to grow by only 2.5 per cent in 2016 and 2.7 per cent in 2017. In light of these projections, the government has recently enacted structural changes to try and move away from its dependency on oil revenue. Only time will tell whether these changes will prove successful.

China – Angola Partnership

In the last decade, China has become one of the main drivers of infrastructure development in Africa. According to the China Africa Research Initiative, between 2000 and 2014, China collectively loaned over US$90 billion to Africa. Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank) is the continent’s primary investor, accounting for US$62 billion over the same period. Three sectors have received a majority of the funding: transportation (US$24.2 billion), energy (US$17.6 billion), and extraction (US$9 billion).

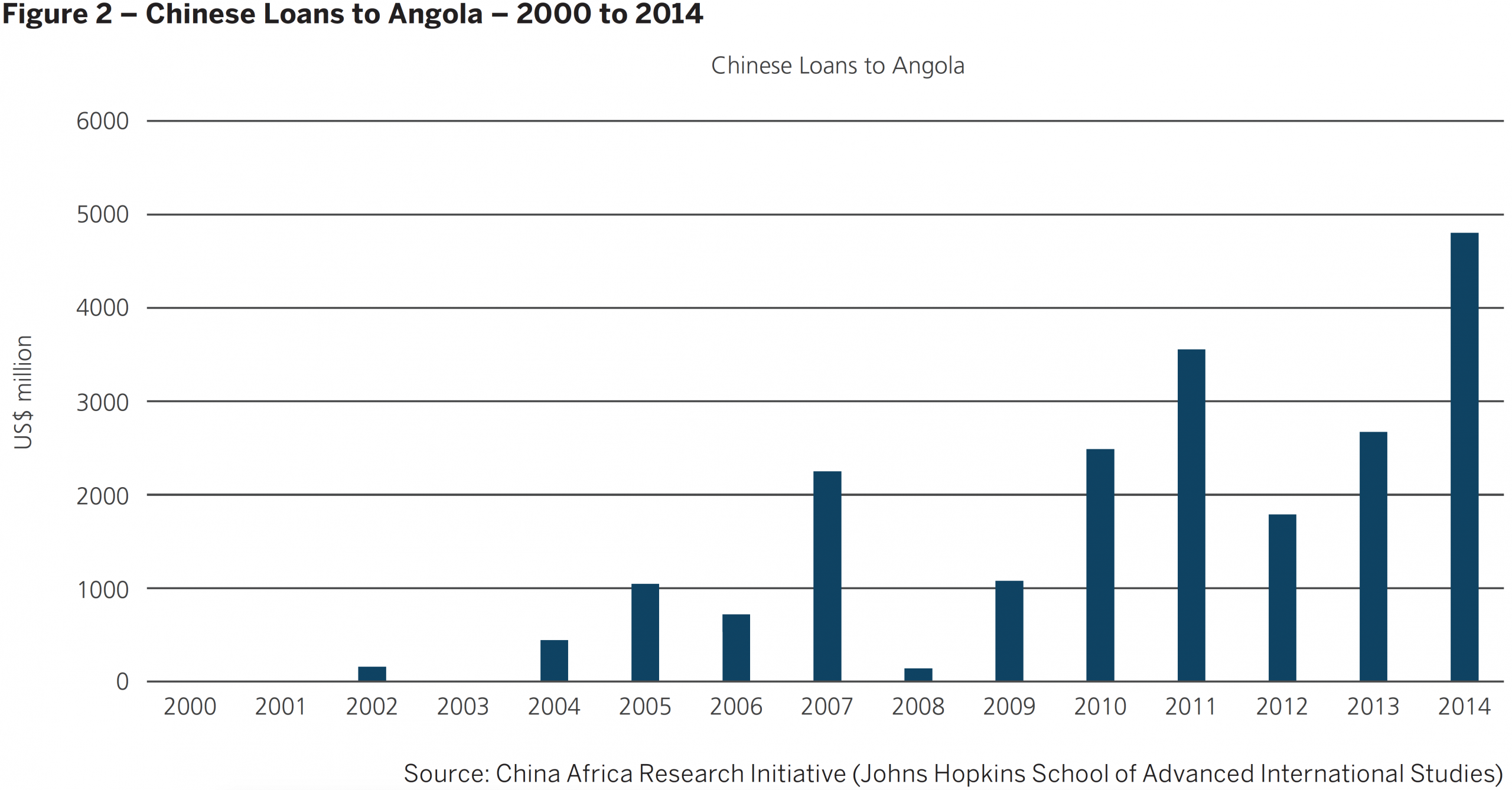

Of all the African nations, Angola has built the closest ties with the Asian power. According to the China Africa Research Initiative published by the John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, “Angola is the primary beneficiary of China’s loans to the continent, accounting for US$21.2 billion, or 23.1 per cent of all Chinese investment in the region.” The largest financier of Angola is the China Development Bank (US$11.3 billion), followed by Exim Bank (US$7.4 billion), and an additional US$2.5 billion provided by other institutions. Data published by the Angolan Finance Ministry shows that between November 2015 and June 2016, the state took on new loans worth US$7 billion from the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, Exim Bank, and the China Development Bank.

Loans between China and African nations generally differ from those provided by global financial institutions such as the IMF and World Bank. Chinese loans entail low-interest rates and rely on commodities, such as oil or mineral resources, as collateral. This type of transaction is known as the “Angola Model” due to the two nation’s close relations and China favouring the African nation with its capital inflow, as published in the 2014 article “China’s Aid to Africa: Monster or Messiah?” by the Brookings Institution. Chinese loans finance not only Angola but a number of African nations suffering from low credit ratings that have great difficulty obtaining funding from the international financial market.

Roughly 50 per cent of all Chinese financing received by Angola has been invested in transportation infrastructure and agriculture-related projects. The remaining balance is allocated to commercial loans to Sonangol, the Angolan state oil enterprise, which has received 84 per cent of all loans granted to extractive industries.

In the past 5 years, China’s loans to Angola have increased significantly (see Figure 2). Consequently, the Chinese presence within the country has become more noticeable. According to Reuters, in 2015, there were approximately 50 Chinese state companies and 400 private businesses operating in Angola, employing a Chinese workforce between 60,000 and 70,000 despite bilateral agreements requiring that at least 30 per cent of the workforce be Angolan. The companies allege there are not sufficient Angolans with the skills to perform top-quality work which is often time-sensitive.

With China’s backing, Angola has greatly improved infrastructure nationwide, notably investing in education. Fifty-six new schools have been built, benefitting a student population of more than 150,000. Additional investments include 24 hospitals totalling 3,340 beds, 10 water treatment plants serving over 1 million people, a television broadcasting station reaching an audience of 9 million, 830 kilometres of roads, 3,200 kilometres of telecommunications cables, and 9 power transmission stations.

In 2014, Exim Bank loaned out US$170 million for three targeted projects: funding the Chiumbedala hydroelectric facility and the Luena sub-station in Moxico province, sponsoring the Cuimba agro-industrial project in Zaire province, and supporting the Institution for Economic and Commercial Management of the Portuguese-speaking African Countries (PALOP) in Huíla province.

In 2016, Chinese investments totalling US$5.2 billion financed 155 projects in Angola. Additionally, the Angolan government has hired Chinese companies to carry out 23 ongoing infrastructure projects, including supplying water and repairing roads in eight provinces at an estimated cost of US$550 million.

Structural Changes

Angola is not relying on China as its sole source of foreign investment. The country is seriously focusing on improving the business environment and streamlining the process for private companies willing to invest in Angola. In 2015, the government enacted a new private investment law (No. 14/15) and created the National Agency for the Promotion of Investment and Exportations of Angola (Agência para a Promoção de Investimento e Exportações de Angola–APIEX). These measures aim to stimulate economic growth, diversify the economy, expand the private sector, and foster greater private-sector participation in Angola’s economic development, according to “2016 Investment Climate Statements, Country profile: Angola” a report published in July 2016 by the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs.

APIEX is housed within the Ministry of Commerce. Its creation is in line with various legislative changes, with the objective of facilitating external and domestic investment and easing access to loans for private investors. As Angola works toward simplifying the process of opening a business, it is also investing in providing training for basic professional skills and guidance for budding entrepreneurs. Industrial centres developing infrastructure and logistic connections are being created as well.

Angolan Ambassador to Singapore, Fidelino Loy de Jesus Figueiredo, regards recent policy changes for foreign and national investment with great enthusiasm: “The new law creates an attractive framework for investors, protecting their interests, but without affecting the State’s welfare. The law also considers the need of having a local working force in the process of developing the economy.”

As for doubts investors have expressed for Law 14/15, the ambassador offers reassurance: “Some investors show concern regarding the repatriation of profits. However, the law is clear and does not place restraints on it.” The law allows for the repatriation of dividends, profits, and royalties following the conclusion of any investment project. However, repatriated tender will be subject to an additional tax. This new tax starts at 15 per cent and can go as high as 50 per cent depending on the amount and the time elapsed between the initial investment and the repatriation in order to encourage reinvestment.

Law 14/15 requires a minimum of 35 per cent local participation or partnership in foreign investments and focuses on six strategic sectors: 1) electricity and water, 2) tourism and hospitality, 3) transportation and logistics, 4) telecommunications and information technology, 5) construction, and 6) media. The 35 per cent minimum will likely prove challenging for foreign investors due to local capital constraints as well as a lack of technical capacity in certain industries.

Oil and mining, two vital sectors of Angola’s economy, are regulated by their own set of investment laws. So, too, is the banking sector, which has a distinct law dictating how foreign investments can be assimilated.

For sectors to which Law 14/15 does apply, the law offers double the fiscal incentive for investing in Angola’s less developed regions compared to areas near Luanda or other major urban centres. Additional tax breaks are available for investors who create more local jobs, generate higher export receipts, and source more local content within their operations.

Although these six strategic areas embraced by the law present distinct opportunities for Angola, two sectors – agriculture and fishing – should receive broader attention. These industries have all the ingredients for much-needed economic diversification, a reduced dependency on imports, and large-scale job creation.

Agriculture and Fishing

According to the Quartz Africa article “Could Angola’s first banana exports in 40 years save its economy?”, the country’s agricultural sector accounts for only 11 per cent of the country’s GDP. Sector growth was a negligible 0.2 per cent in 2015, and only a third of Angola’s arable land has been cultivated. Historically, Angola was a net exporter of agricultural products during its colonial era under Portugal, and these days, it certainly possesses the young workforce, temperate climate, and arable land to expand its agricultural and fishing sectors. Although some progress has been made, there is still a long way to go to alleviating Angola’s dependency on food imports.

Recently, for the first time in over 40 years, Angola exported 17 tonnes of bananas to Europe. The recent growth in the country’s banana production was fuelled by Chinese investments under the “Angola-Model,” after agreements trading oil for infrastructure development were signed between the two countries back in 2004. According to the Reuters’ report “Angola’s blooming banana plantations offer new hope for farming,” banana production grew from 76,000 tonnes in 2012 to 247,000 tonnes in 2013, not only ending banana imports but also allowing for exports to the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo.

Cash crops, such as sugar and coffee – once major Angolan exports – are again being produced, albeit on a smaller scale compared with the period prior to the 1975–2002 civil war. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, Angola produced 12,000 tonnes of coffee in 2014, its highest production for decades but well below the record 200,000 tonnes from the colonial era. Most coffee growers are small-scale and struggle to market their crops while constantly battling pests and disease.

In May 2015, a Portuguese firm, Nabeiro, announced that it was buying out the Angolan state coffee firm, Liangol, whose operations it had been running for almost 15 years. According to The Economist, Nabeiro paid US$1 million for Liangol and has now taken over Angola’s Ginga coffee brand. This is the kind of private investment that Angola needs to rebuild its agribusiness. Privatisation certainly has its risks, but private companies have a clear monetary incentive to be efficient and profitable, while state companies frequently run at a loss.

In the sugar and bio-fuel industries, Biocom, a public-private partnership, has set a challenging target for 2020. The company, which owns a 100,000-acre farm located 300km east of Luanda, in Malanje, aims to produce 256,000 tonnes of sugar by decade’s end, which would secure 50 per cent of Angola’s domestic consumption. Additionally, the company projects 33,000 cubic meters of ethanol production and 235,000 MWh of generated electricity. According to the 2016 Rede Angola article “A cana-de-açúcar que pretende adoçar o país,” Biocom will produce 47,000 tonnes of sugar, 16,000 cubic meters of ethanol and 155,000 MWh of electricity The firm is part of a partnership which includes the state oil company Sonangol, the government investment fund Cochan, and Brazilian construction company Odebrecht.

Angola’s fishing industry has also been recovering, growing from 277,000 tonnes in 2012 to 300,000 tonnes in 2013, of which 85 per cent is consumed domestically. The country’s target output is slated to increase to 400,000 tonnes in the coming years. With rich coastal waters and a well-watered interior, active fisheries which include rivers, freshwater lakes and reservoirs, 1,600km of coastline, and 330,000 km2 of exclusive economic zone waters, Angola is naturally poised to increase the size of its fishing industry significantly.

Developing aquaculture and expanding the fishing industry would generate jobs and contribute to food security and poverty reduction, especially in rural and coastal areas. It would also have a decisive social impact on certain subsectors: one-third of Angola’s animal protein comes from fish, and artisanal fishing represents 30 per cent of the country’s total fishing activity. Many involved in the industry are organised via co-operatives, and over 80 per cent of their members are women.

The country is also developing its fish-farming potential. Its first major initiative at the Mucoso centre near Dondo, Kwanza Norte province, opened in April 2014. Bengo province, near Luanda, has several large lakes and lagoons that support traditional artisanal fisheries. The Kwanza River is also home to several existing and new dam projects which could be stocked with additional farmed fish.

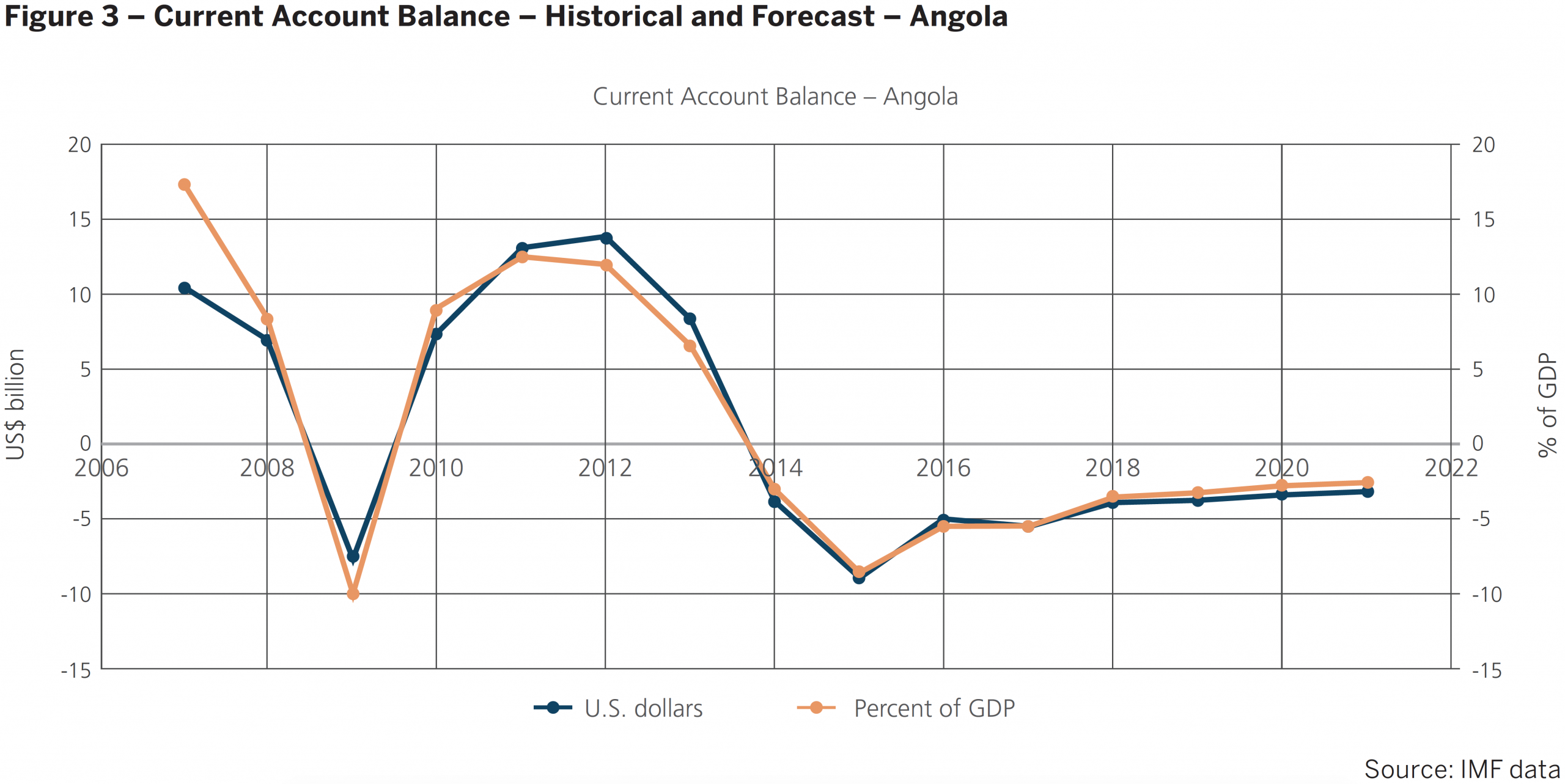

Angola’s Current Deficit

The necessity for economic diversification is blatantly evident; however, effective measures towards reaching this goal could have come earlier. The global drop in oil revenue, coupled with an increase in national expenditures, has led to Angola’s first fiscal deficit since 2009. Since 2014, the country has been running a deficit which is forecasted through the next decade (see Figure 3). Lower oil prices and higher imports have narrowed the resource-rich country’s surplus. Oil export revenues, which dominate foreign-exchange earnings, have declined as global oil prices have fallen, highlighting the need for economic diversification and decoupling public finances from the oil sector.

Angola has implemented some expenditure measures in an effort to reduce the deficit, including ending fuel subsidies in early 2016 and freezing public sector hiring. With oil prices projected to remain below recent peaks, fiscal revenues are expected to bottom out, and as a result, deficits are likely to increase despite efforts to restrain spending.

Inflation, which spiked to 23 per cent in the first quarter of 2016 from 2015’s annual rate of 14.3 per cent, thereby exceeding the central bank’s target, remains a problem. According to a report published by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs, “2016 Investment Climate Statements, Country profile: Angola,” the high inflation is a result of currency devaluation as well as the cessation of the government’s fuel subsidies. Concern over inflation has led the central bank to hike interest rates. With government spending remaining constrained, the elevated inflation has weakened consumer spending.

Diversification Is the Key

Low oil prices foreshadow the coming years with uncertainty. One strategy to mitigate crisis is to diversify the economy. Agriculture is expected to play a key role in boosting the country’s exports and generating foreign currency earnings.

Equally important is fostering investments in infrastructure, deepening financial sector reforms, developing professional skills, and improving the business environment. Investing in local industry will result in a gradual reduction of imports, which is essential in a scenario of weak local currency.

Angola’s implementation of Law 14/15 regarding foreign investment is an important step towards streamlining the business environment for external investors. Reducing bureaucracy and facilitating credit are also measures the government is trying to implement. Notwithstanding these reforms, the country’s legal framework still needs adjusting. Income inequality, unemployment, and poverty remain challenges as do persisting regional economic imbalances. Transformative investments are required to decongest large cities and reconnect them with major economic growth poles, particularly in rural areas.

“I see that the main sectors that will benefit from additional foreign investment in Angola are mining, fishing, agriculture, and energy,” confirms Ambassador Figueiredo. In addition to mining and energy, which are already being extensively explored, fishing and agriculture are two sectors the government plans to expand significantly. The ambassador also believes that “developing the professional skills of the base worker, training managers to be efficient, investing in infrastructure, and gradually increasing institutional capability are very important aspects that should be tackled in this process.”

Under its National Development Plan for 2013–2017, the government is contemplating a territorial development strategy to create a network of development poles. The country currently has a National Urbanisation and Housing Programme, a 2015–2030 Metropolitan Plan for Luanda, and several ongoing urbanisation projects.

In the event that oil prices rise again and Angola is faced with another bonanza period, will the country follow the same path it did post-civil war, relying on easy, instant revenue rather than investing in long-term socio-economic development? Ambassador Figueiredo emphatically replies, “There is no turning back from the government’s decision of diversifying the economy and the reassessment of national development priorities. In [the event of the] eventual rise of oil prices, the consequent availability of this extra income will be additional to the revenue sources from the new strategic areas defined by the government.”