Ink has been an important medium in Chinese culture for over two millennia. In ancient times, emperors, monks, scholars and artists mastered the marriage of precision, concentration and balance that calligraphy and ink painting demanded. Early forms evolved from scripting stately forecasts on tortoise shells and the shoulder blades of oxen to, in the latter Han dynasty in the 3rd century, creative expressions on silk or paper – beautiful interpretations of natural scenery, like birds, flowers, mountains and bodies of water.

Today, Chinese artists across the world have used ink to push their creative boundaries, giving this time-honoured medium new purpose. Now, two organisations have joined forces to display style-bending ink work created by some of the Greater Bay Area’s most exciting artists.

Spearheaded by the Cultural Bureau of Macao and Culture and Tourism of Guangdong, “Wild Imagination: Contemporary Ink Art in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao from 2000 to 2022” features over 50 artists from Guangzhou, Hong Kong and Macao and 80 pieces of ink artwork. The exhibition, which opened at the Guangzhou Museum of Art in December 2020, will run until mid-June at the Macao Museum of Art (MAM), aiming not only to display great work, but also to show the breadth and variety of contemporary ink art across the Pearl River Delta.

Spanning photography, video, digital art, installations, painting and calligraphy, this ambitious exhibition is setting out to show that ink art is alive and well in our bustling economic region.

Historic forms meet modern times

Traditional artists – as in those creating ink paintings as far back as the Han dynasty – did not aim to depict objects realistically, but rather express humanistic ideas through their imagery. That popular philosophy endured until the early 20th century, when the West introduced new media and ways to approach art. While Chinese artists still relied on ink to produce work on scrolls and canvases, they began to seek other ways to express their thoughts and emotions. Now ink art is offering today’s artists new ways to communicate ideas in forms and styles that unite, if not blur the line between, Chinese and global influences.

Curated by the revered artist Pi Daojian, the associate director of the Curatorial Committee of the China Artists Association, this collaborative exhibition deeply explores how the Chinese traditional context is reflected by the Greater Bay Area’s contemporary ink artists. “Guangzhou, Hong Kong and Macao embrace cultural diversity, and [the region] nurtures diverse artistic experiments,” Pi explains. “In the dynamic structures of Chinese contemporary ink art – ranging from conventional to academic to experimental – the region has showcased excellent artwork.”

He adds that the exhibition also aims to advance Chinese contemporary ink art. Those efforts become clear in the one theme that reigns supreme: the digital narrative. Photography, video, animation and music feature widely throughout the exhibition. It’s ink work without ink, offering a new way to engage with the medium, according to the team behind the exhibition.

“In contemporary ink art, we sometimes see ink in the work, but sometimes we don’t. Those artworks [still express] the traditional spirit of ink. We’d like the audience to experience [that spirit], even if they don’t see ‘ink’,” says exhibition coordinator Vivien Lei Heong Hong.

“I think the whole process relates to the Zen philosophy: First there is ink, then there is no ink, then there is.”

The Macao exhibition also differs from its Guangzhou counterpart in a couple of ways. For starters, the show at MAM displays 10 additional different pieces from nine Macao artists. But it also differs in its layout. The show separates the artworks into four categories: nature as poetry, wild imagination, metaphysical thinking, and landscapes in ink and water. The last category opened the exhibition in Guangzhou, featuring contemporary interpretations on mountains and waters – traditional ink art imagery. Conversely, it closes the MAM exhibition, as if bringing the past into the present before guests depart.

“We put ‘landscape in ink and water’ at the end, [and] we hope the audience can gain a sense of belonging to these traditional ink art symbols towards the end of the show,” explains Lei.

Going with the flow

Crowds have so far responded positively to the show’s messages, themes and clever abstractions. According to Lei, since its opening on 9 May, it has drawn over 9,000 visitors, many of whom have been able to experience the work of leading Macao artists like Cindy Ng Sio Ieng.

Born and bred in Macao, the Beijing-based digital artist is considered a contemporary ink art pioneer, having exhibited her works far and wide in solo and collaborative exhibitions in Taiwan, Beijing, Shanghai, New York and Seattle as well as her home city. That global experience shines in her work. Ng often meditates on her culture and heritage in inventive digital pieces. Her colour-saturated, abstract work Video (2020), for instance, speaks to universal struggles over the past two years with reference to her experience in Macao.

“I started working on this piece in April 2020, when I was stuck in Macao for months. I really missed the days when I could stroll freely in nature, watch colourful flowers and enjoy glorious sunshine,” she says. “In this work, I use iridescent colours – different from my usual practice of five shades of ink. I hope the colours – somehow expressing my desires [for freedom] – could comfort people who also feel depressed during the pandemic.”

Video, like so much of Ng’s work, integrates new technology into the traditional art form. The flowing ink continually shifts according to Macao’s real-time weather data she collected. Temperatures affect the colours, while wind strength and direction influence the ink’s movement. The background music also goes with the flow, following no set pattern but rather moving organically.

“The ultimate goal of traditional Chinese paintings is to convey an abstract feeling, with which elites express their views on nature. As [Chinese modern artist] Liu Kuo-Sung said, ‘revolutionise a stroke!’ It means ink should not carry the feeling of a brush. So my flowing ink – presented in digital videos – is to communicate the dynamic of ink art on its own,” she shares.

Digital technology breeds new possibilities

Other artists on display likewise turn to technology to expand on traditional motifs, such as the limits of language and text. Award-winning Hong Kong-based digital artist Hung Keung, for example, forges a connection between imagery and text in Four Seasons (2020), a six-channel digital installation on display at MAM, that calligraphy simply cannot.

The channels chart seasonal changes that a solitary flower undergoes, to which kinetic Chinese characters – such as ‘soil’ and ‘rain’ – react. The image of the flower – beautiful and forlorn with a full flower head – is staggering. The characters are imbued with personalities, relating to both their literal meanings and the seasonal changes. For example, when the flower withers, the Chinese character on the screen changes to one of pain or sorrow.

Hung, an associate professor in the Department of Cultural and Creative Arts at the Education University of Hong Kong, says he drew inspiration for this installation from his years-long research on Chinese aesthetics, philosophy, digital art and text. “Traditionally, Chinese calligraphers could express their emotions through cursive and semi-cursive scripts, but today, people type on their phones [instead of handwriting]. You can’t tell one’s emotion through their typing; that’s why emojis have emerged,” he says. “Text somehow has become a cold vessel of meanings, but I believe technology does not limit text to its function but [instead] can make it flow with personality.”

Even the way the installation is set up creates new meaning. The channels are mounted on a small slope in a dark space, inviting the audience to experience the work in an almost ethereal setting. Having shown his work in art hubs like Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong previously, Hung says he was impressed by the attention to detail that has gone into this exhibition.

“Any trivial changes in the installation will affect the audience’s experience. In this exhibition in Guangzhou and Macao, I can see the production team’s great effort to present my work in its most exact form.”

Return to imagery

Guangzhou-born artist and curator Shen Ruijun, meanwhile, represents the intersection of cultures. She has buried herself in researching Chinese gardens for around eight years and says she is captivated by the abstract expression of traditional Chinese ink art, but she also admits she is greatly influenced by Western art from the time she spent studying at Montclair State University and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her installation, Pond with White Snow (2016), integrates both sources of inspiration – elements of Chinese and Western gardens alike, the former often poetic and contemplative, the latter expressed through clear visual cues.

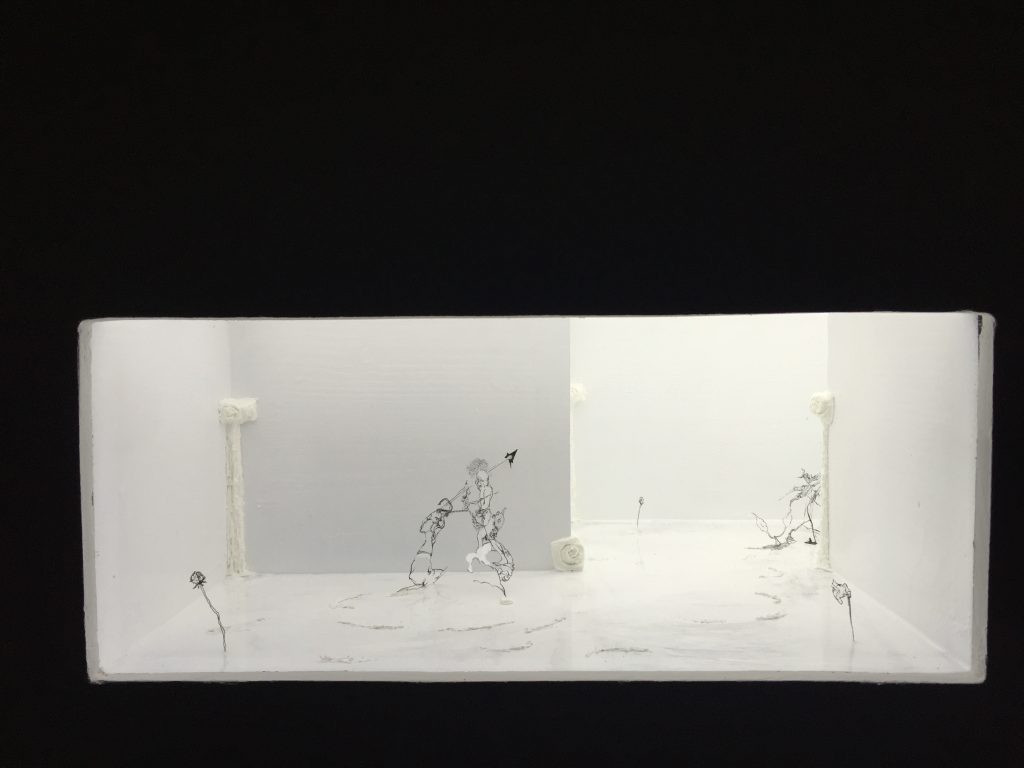

Mounted in a small, recessed wall – only 14 cm by 58 cm by 34 cm – the installation illustrates a battle with a half-human, half-beast figure. Flowers planted around that figure imply the ground is a pond. The recess is also decorated with Roman pillars.

“A pond is an abstract element in a Chinese garden, as it reflects the surroundings – the surroundings somehow become part of the pond itself,” she explains. “On the surface, you can see the reflection of some figures and my drawing of their shadows. Together they create an abstract landscape, because the reflections will [come and go] according to the light, but the drawings remain.”

The centrepiece figure, on the other hand, celebrates human power “and somehow expresses a sublime yet cruel beauty,” while the withered Roman pillars speak to immortality, “which suggests an ironic co-existence between human and nature. It also shows the differences between East and West.”

The installation, part of Shen’s popular series Boxes of Curiosity (2013), is well suited for the exhibition, according to the artist. Shen believes it expresses the poetic and contemplative nature of ink art yet is embedded in contemporary art practice.

That is a theme that MAM’s Wild Imagination circles back to often: past meets present. Throughout the exhibition, visitors witness intense individual creativity, a blend of Eastern and Western influences, traditional art forms and imagery, digital technology, and narratives that examine personal and social issues. Even with all the variety, one thing remains constant. Wild Imagination always conveys the poetic nature and traditional feel of ink, the timeless Chinese medium that artists across the Greater Bay Area continue to reinterpret in exciting new ways.