One day in November 2001, Professor Wang Yitao took a helicopter from Hong Kong to Macao, where he was picked up by a government car to attend a meeting with then Chief Executive Edmund Ho.

“He invited me to come to Macao and develop Chinese medicine. He offered funds, an initial MOP10 million,” Wang recalled in an interview. “I said Macao should complement the development of medicines in China and become a platform to unite technology from abroad and the best traditions of the industry at home.”

The two men reached an agreement. Wang left with an appealing salary and a free 200‐sq metre apartment at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology for lower income and a 280‐sq metre laboratory.

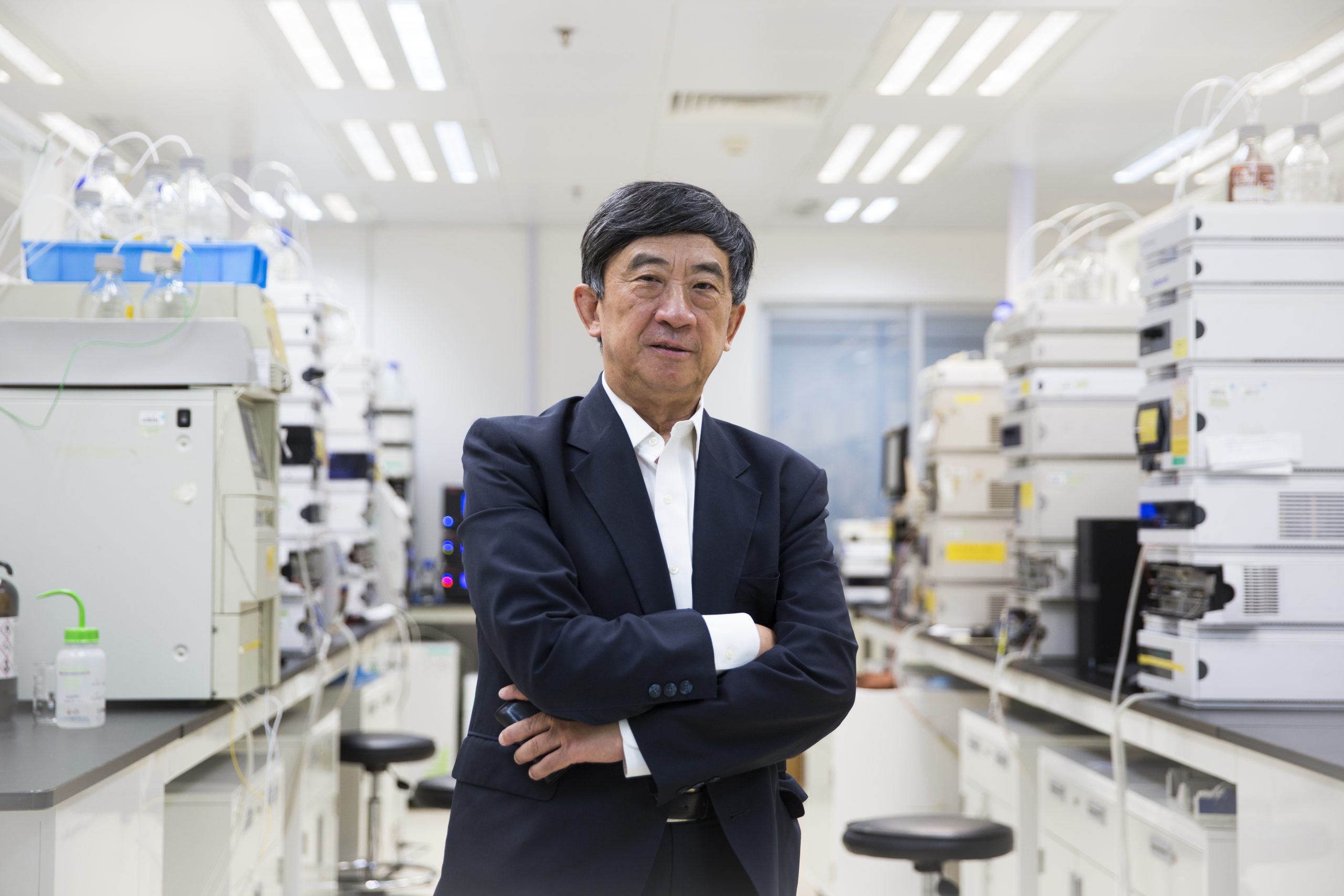

Now, 17 years later, Wang has state‐of‐the‐art laboratories covering 28,000 sq metres on the campus of University of Macau in Hengqin and leads a team of 36 specialists recruited from top universities around the world.

He is director of the Institute of Chinese Medical Sciences and of the State Key Laboratory of Quality Research in Chinese Medicine, one of two such laboratories at the university.

“People in Europe and North America do not see Chinese medicine as a drug but as a supplement,” he explained. “They say that it is not based on science; we are changing that. We’re conducting the scientific research needed and publishing it; we produce an academic magazine [Chinese Medicine] in English.”

He proudly shows visitors around the laboratories, equipped with the newest equipment from Germany, Japan and the United States. On the wall hang the photographs of his staff, who include graduates from the universities of Edinburgh, Yale, Cambridge and Stanford, as well as UCLA and the National Cancer Institute in the US.

“In aeronautics and aircraft carriers, China is close to the world standard,” he noted. “But she is weak in pharmaceuticals. In the top 500 drug firms in the world, there is not a single Chinese firm. The Chinese government wants to build a company bigger than Pfizer.”

Betting on Macao

The establishment of the Institute of Chinese Medical Sciences (ICMS), the city’s first research‐oriented institute, in 2002 was a direct result of that fateful meeting between the Professor and Edmund Ho. Devoted to promoting the research of Chinese medicine and nurturing local talents in biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences, the institute has trained over 500 Master’s of Science and PhD students.

They say that the Chinese medicine is not based on science; we are changing that. We’re conducting the scientific research needed and publishing it.

Wang Yitao

In 2010, just two years after the first class of PhD students graduated, ICMS hit another major milestone when the University of Macau was chosen to host two State Key Laboratories.

The State Key Laboratory of Quality Research in Chinese Medicine (SKL‐QRCM), the first of its kind, was jointly established by ICMS and Macau University of Science and Technology (MUST). The lab co‐operates with the State Key Lab of Natural and Biomimetic Drugs at Peking University in innovative research on Chinese medicine (CM).

Quality evaluation of CM is the lab’s main focus of research, broken down into five key areas: effectiveness, safety, stability, controllability, and systemic research. The lab aims to be a platform for international co‐operation, innovative development, and systemic research in CM.

Since 2011, the SKL‐QRCM and ICMS have published 1,598 academic papers, 13 academic books, and applied for 31 patents. The papers have been cited 23,918 times, an average of 15.0 citations per paper.

The lab successfully passed the mid‐stage assessment in 2013, its achievements garnering high praise from the Expert Committee of the Ministry of Science and Technology.

In addition to their success in research, publication and patenting new processes, the SKL‐QRCM has made important strides in becoming a global collaborative platform for CM.

These collaborations have advanced innovation, particularly in the areas of cancer, auto‐ ‐immune and respiratory diseases, as well as development of systematic drug screening technologies. A partnership with the US Pharmacopeial Convention (USP) to establish quality standards for Chinese medicine will aid the lab’s efforts to internationalise CM. The drug standards set by USP are used in more than 140 countries.

The ICMS and SKL have an annual budget of MOP26 million (US$3.24 milllion), of which MOP10 million (US$1.24 million) comes from the FDCT (O Fundo para o Desenvolvimento das Ciências e da Tecnologia) and MOP16 million (US$2.31 million) from UM. Each year 10,000 young people tour the two centres, part of Wang’s effort to popularise and explain the valuable work they are doing.

Second-generation excellence

Professor Wang’s story is as remarkable as the campus where he works. His father was Wang Yusheng, one of China’s most famous pharmacologists of his era; he studied at the Peking Union Medical College, established by foreign Christian missionaries.

Born in 1949, Wang grew up in a house full of bottles of Chinese herbs and dinner conversations of how to cure the sick in an era when Western medicine was too expensive for all but a small number of elites.

In 1966, when Wang was 17, Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution. Like millions of other city teenagers, Wang was sent to the countryside “to learn from the peasants.” He spent the next decade as a farmer and a worker, earning six fen (RMB0.06) a day.

The government reinstated the national university entrance exam, the gaokao (高考), after its absence of 11 years. Many consider the 1977 exam the most competitive in China’s history with less than five per cent of the 5.7 million people who took the exam qualifying for university. Wang was one of them.

He attended Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (CDUTCM), graduating with a bachelor’s degree in 1982; he was 33 years old. An outstanding student, Wang was invited to stay on as a teacher and became the head of his department, the first to be chosen by the members of the faculty. During his tenure, Wang helped establish the educational system for CM at CDUCTM, and went on to serve as dean and vice president of the university.

In 1996, he was invited to join the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (CACMS) in Beijing where he was deputy director. There he worked together with Tu Youyou, who would go on to become the first Chinese Nobel laureate in physiology and medicine in 2015.

In her speech to the Nobel prize committee in Stockholm on 7 December that year, she said: “Chinese medicine and pharmacology are a great treasure house for medical research which should be explored and raised to a high level. Adopting, exploring, developing, and advancing these practices would allow us to discover more novel medicines beneficial to world health care.”

Wang believes that he is carrying on Tu’s work. “She was limited in what she could do. Her facilities and laboratories were not so advanced,” he explained, a reality that makes her award‐winning discovery all the more impressive. “Now, we have state‐of‐the‐art equipment and can do much more.”

In 1999, three years after joining the staff of CACMS, Wang was appointed by the Ministry of Science and Technology as one of the two chief scientists for the first Chinese medicine project under the National Basic Research Programme. Established by the government in 1997, the programme (also known as 973 Programme) aims to develop basic research, innovations, and technologies aligned with national priorities in economic and social development.

The next year, Wang moved to the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, where he was appointed head of research of CM. Its government had a similar idea to that of Edmund Ho: to find ways to modernise and commercialise CM.

While the city enjoyed an abundance of capital and talent, something was still missing for Wang. Only two years later, he accepted Ho’s offer to come to Macao where he’s thrived ever since.

Commercialising Chinese medicine

The next stage is to turn the research done in the laboratories into products for sale at home and abroad. For this, Wang chose to partner with the Taiji Group of Chongqing, one of China’s top 500 enterprises and top 10 pharmaceutical firms. According to its 2017 annual report, it posted sales last year of RMB8.74 billion (US$1.26 billion), up 9.84 per cent on 2016, and had assets of RMB10.66 billion (US$1.54 billion), up 11.91 per cent.

The group boasts 12 pharmaceutical factories, more than 30 pharmaceutical and commercial companies, of which 3 are listed, and produces more than 1,500 Western and Chinese medicines.

The 20 pharmaceutical firms in Macao are small and traditional, family businesses that prefer to continue their normal production. There is little interest in, or land available for, large‐scale production.

“Sichuan is the home of Chinese medicines,” Wang noted. “It is a treasure house of herbs. Many of the senior managers of Taiji studied under me. I helped the firm develop products 20 years ago.”

Twenty years from now, consumers from Kolkata to Chicago may be purchasing the fruits of this current partnership, Chinese medicines first developed in the laboratories of the University of Macau.