TEXT Lucian Hoi

Macao’s contribution to the world of scientific research is often overlooked. Here are eight major scientific discoveries that this small, ambitious city has made over the past 20 years.

Almond cookies, pork chop buns and egg tarts. Glamorous entertainment resorts. Throngs of tourists taking selfies outside an ancient church which was almost totally lost to fire. These are the images that are most likely conjured up when people think about Macao. What these people probably won’t muse on, however, is the Chinese city’s contributions to the world of science and research. It may have a more than 400-year-old history but Macao has a population of less than 700,000 people and a land area of just 32.9 square kilometres. So it can’t have made much of a contribution to science, can it?

It can. Despite its small size and population, Macao has actually contributed much to mankind’s ever-growing pool of scientific knowledge and understanding. And it’s set to contribute much more in the future, thanks to the central government designating Macao as part of the ‘scientific and technological innovation corridor’, alongside Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Hong Kong, in the blueprint of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. But what has Macao discovered over the years and how do these discoveries help the world’s scientific understanding? We have chosen eight major discoveries in the city that have been made over the past 20 years, since the 1999 transfer of administration, so you can discover Macao’s recent scientific prowess for yourself.

The portable nuclear magnetic resonance platform

With the steadfast support of both the central and Macao’s governments, the city has taken a giant leap forward in its scientific research work since its transfer of administration to China in 1999. As a result, there have been a number of cutting-edge discoveries that have been made in the territory which have been celebrated on a global level. And microchips feature a good few times in this list over the years. There have been many studies involving this tiny unit that’s used in an integrated circuit.

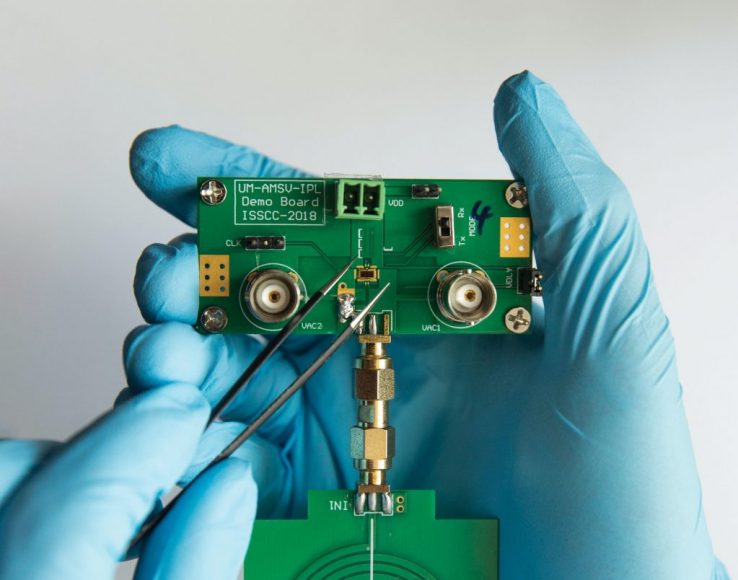

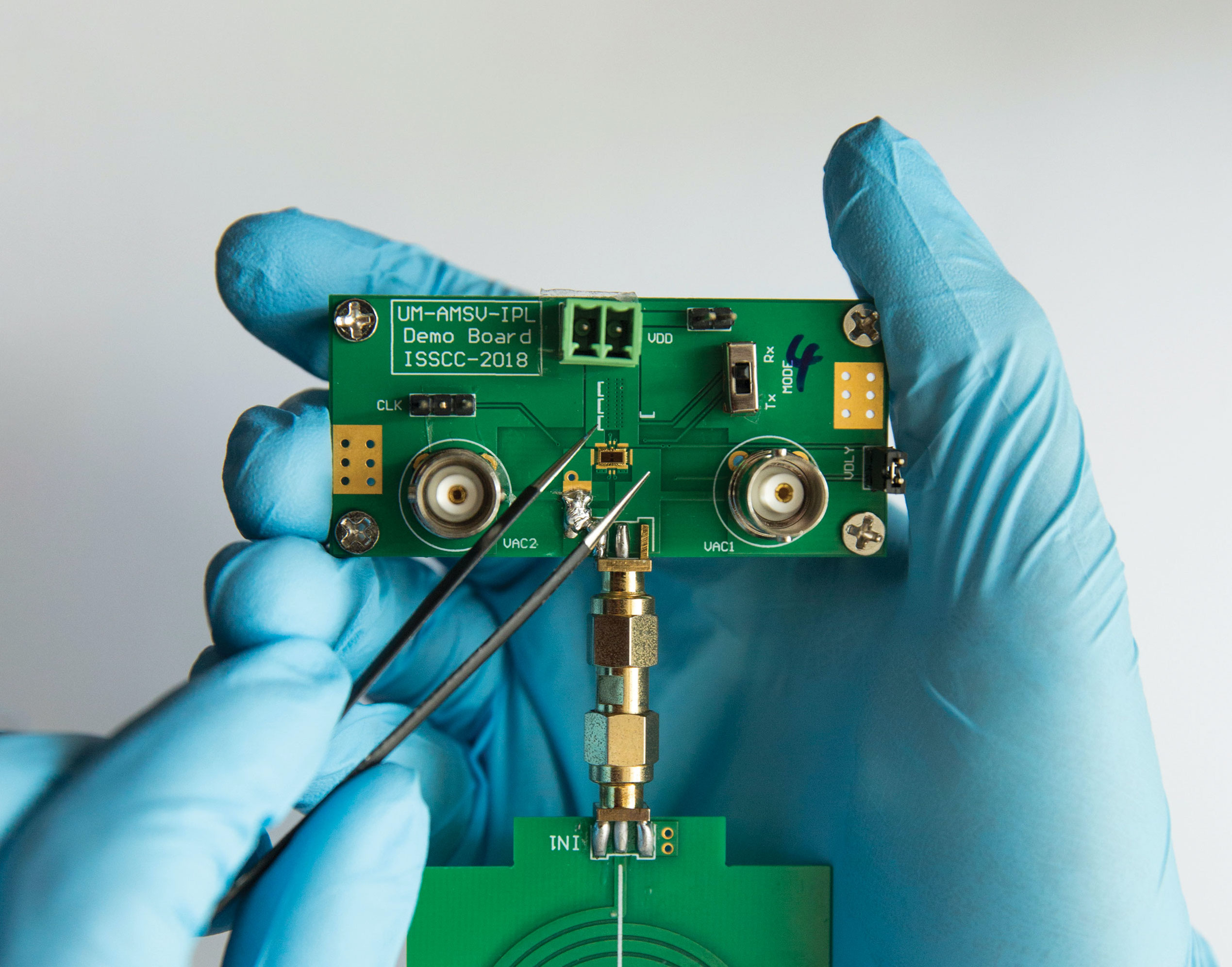

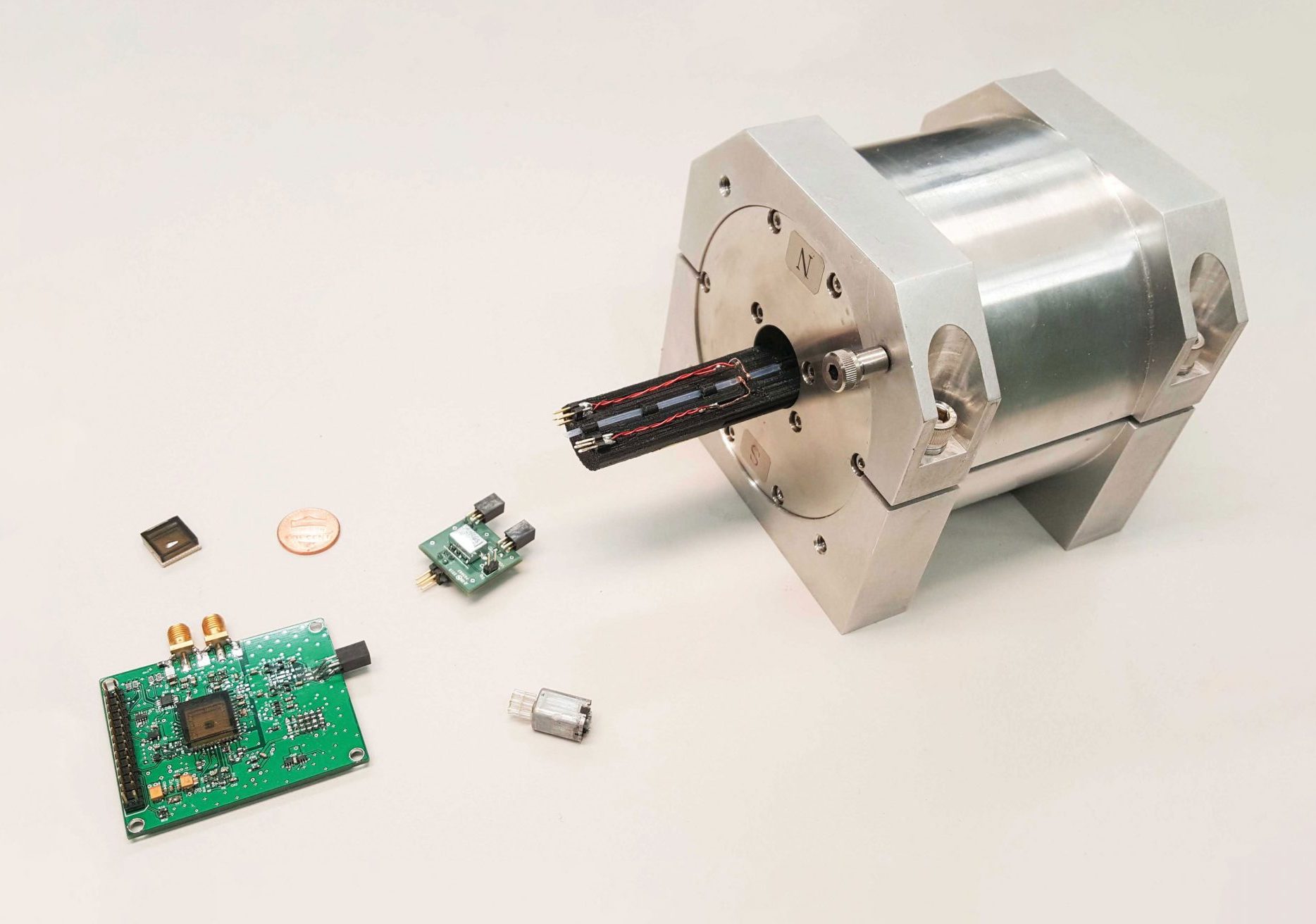

One such discovery that uses microchips was made just this year – and it’s led to an invention that’s already garnered much international praise. The portable nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) platform came about as a result of a years-long collaboration between the University of Macau (UM) and Harvard University in Massachusetts in the US. The NMR spectroscopy technique is a powerful analytical tool used to determine the presence of bacterial contaminants in complex biological samples, so this new platform is designed to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of all NMR tests. This may not sound like a major scientific discovery but it certainly is because it can also be applied in biological diagnostic tests. Conducting blood and protein tests, for instance, with the new platform will be much cheaper and faster than using any traditional NMR testing method.

Advanced integrated circuits technology, alongside semiconductor chips and portable magnets, have made this new platform possible. “The current [NMR] diagnostic tests usually require the use of large devices and a lot of time and skilled professionals,” says Dr Lei Ka-Meng, the UM researcher behind the project, “but with this proposed NMR technique, we no longer need to use large devices for diagnostic tests and the cost can be brought down from between MOP 500,000 and MOP 600,000 [US$62,000 – $75,000] to between MOP 30,000 and MOP 40,000 [US$3,700 – $5,000]. This technique allows diagnostic tests to be conducted outside the centralised laboratory. Even clinics in remote regions can afford it.”

The new platform has the potential to seriously change the way that important NMR tests are done on a global scale. But it’s not the only discovery made by the UM over the years that could have a great impact upon the world of scientific research. In 2017, the UM’s State Key Laboratory of Analogue and Mixed-Signal VLSI (SKL-AMSV) – which was officially inaugurated in 2011 under the approval of the Ministry of Science and Technology – was behind a new fast and convenient point-of-care pathogen detection method which utilises a digital microfluidic (DMF) chip, an emerging chip technology. According to the UM, the lab, which is one of four state key laboratories in the city and more than 200 similar units across China, is ranked second in the world in terms of the number of academic papers in chip design that it has published.

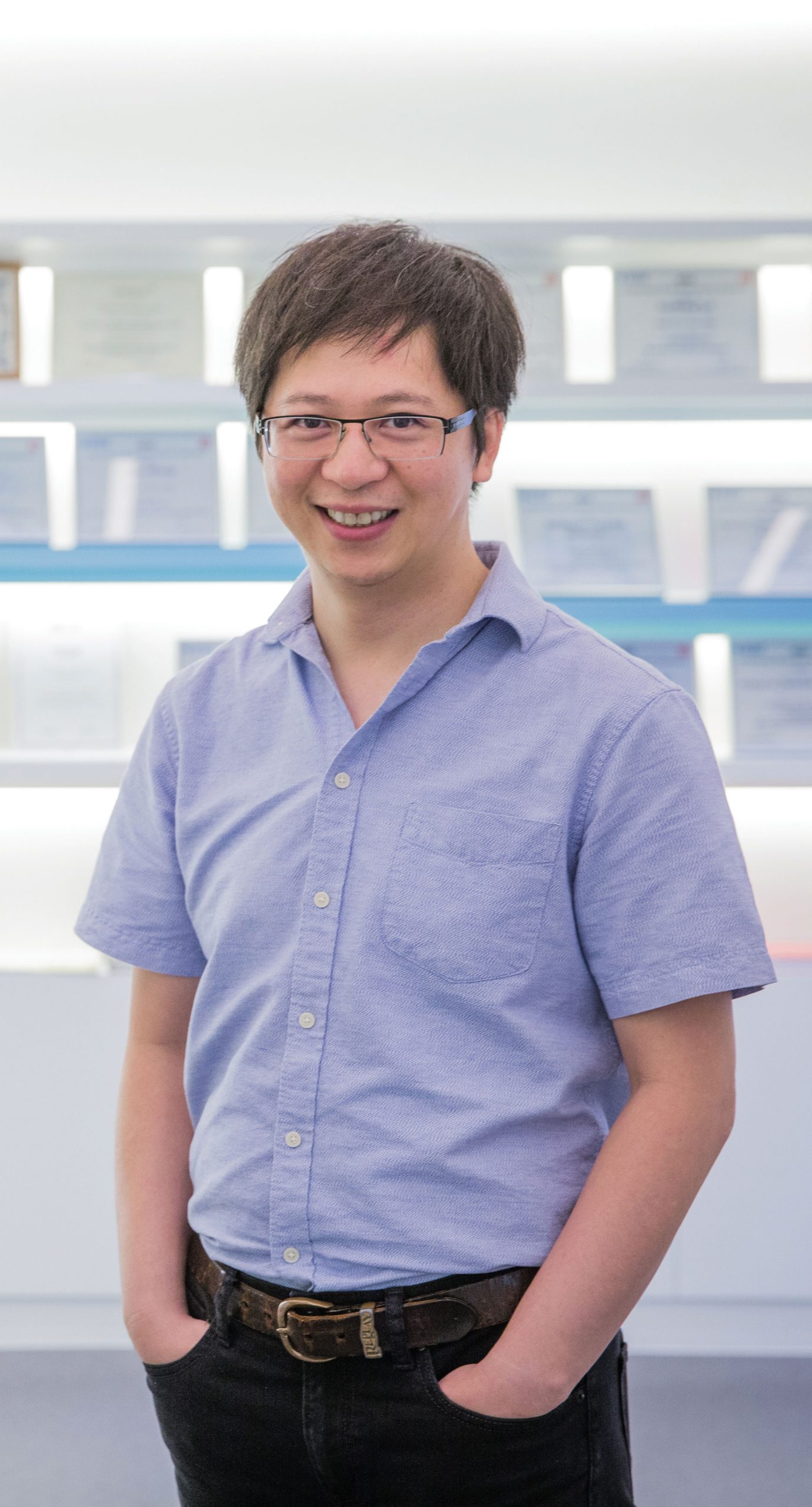

“Our dimensions, in terms of human and space resources, are still of a small scale,” says SKL-AMSV’s associate director of research, Professor Elvis Pui-in Mak, “but the work [that is] developed [at the lab] is of extremely high quality, with world-class results, and we have the ambition to contribute further, with great determination and hard work, for the development of state-of-the-art electronics in Macao and [Mainland] China. We have been training Chinese researchers to develop independent innovation rather than using reverse engineering to replicate imported chips.”

Prof Mak says that, starting from 2012, ‘a wide variety of biomedical and chemistry-related circuits, systems and industrialisation-ready prototypes with high sensitivity and rich functionalities have been developed’ at the lab. For instance, the prototype of a portable automation device and platform for DNA detection called Virus Hunter has been developed in accordance with the lab’s patented DMF technology. Digifluidic Biotech Ltd, which was founded in nearby Hengqin in 2018, is described by the professor as ‘the first spin-off company of the University of Macau’. The company is now working on the development – as fast as it can, given the current pandemic – of a test kit for the rapid detection of COVID-19 using the Virus Hunter. “The research team has been in touch with relevant medical units,” says the professor, “and the system will be available to frontline medical personnel upon verification.” As we went to print, the test kit was not yet ready for use.

The active power filter

Macao isn’t just world-class when it comes to microchips. It’s also world-class when it comes to energy research – and it excels in its work on active power filters. An active power filter (APF) is a device that is dedicated to improving the quality of electrical energy and the efficiency of its use. APFs can provide crucial support for the development of smart grid technologies, which are self-sufficient systems that can find solutions to problems quickly in an available system that reduce the workforce and target sustainable, safe and reliable electricity to consumers. These technologies are considered by many governments – including China and the US – to be an effective way to reduce energy consumption and to mitigate the contribution to global warming. In short, APFs are vital devices in creating the electrical energy systems of the future.

The University of Macau has played a key role in APF research over the past few years. And in the same vein as its NMR work – it has discovered a way of using APFs that can reduce costs and improve efficiency for all. Since 2005, the UM’s power electronics team has been focusing its energy on the development of hybrid power filters, which are a combination of APFs and passive power filters (PPF). As opposed to APFs, PPFs do not require an external power source to run but together with APFs they can reduce the cost of power filters and operating losses.

In 2015, Prof Wong Man Chung, head of the university’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, revealed that the power electronics team had successfully installed the first capacitive grid-connected hybrid power quality compensator at the Macao Water Supply Company a year earlier. He added at the time that the compensator had been ‘operating smoothly’ with an operating efficiency reaching 98.8 per cent when fully loaded. He said that had brought ‘substantial economic benefits’ to the water company. The professor said the compensator is characterised by its ‘medium price range and high efficiency’ and it was also revealed that the design had been patented in both China and the US.

The power electronics research team has, over the past few years, participated in a number of energy conservation projects at the university. Between 2012 and 2017, the UM ranked among the top three institutions in the world in terms of publishing the most papers in the area in three respected power electronics academic journals: ‘IEEE Transaction on Industrial Electronics’, ‘IEEE Transaction on Power Electronics’ and ‘IET Power Electronics’.

The new species of insect

Toxorhynchites macaensis, Chlorophorus macaumensis and Crematogaster macaoensis. Sounds like a tongue twister but these are actually the names of the only three species of insect – a mosquito, a beetle and an ant – that paid homage to Macao in their scientific names prior to 2017. Then a young researcher from Macao, Danny Chi-man Leong, arrived on the scene. On his own, he discovered a whole new species of ant in the city – Leptanilla macauensis.

Since 2017, Leong, who was then a Master’s student but is now studying for his PhD at the University of Hong Kong as well as working as an adjunct instructor at the University of Macau, has been known locally as Macao’s ‘Ant Man’. He discovered Leptanilla macauensis in Ilha Verde, a small hill situated in the northern part of the Macao peninsula. It was a whole new species of ant and was also the first new insect species that had been discovered in the territory since two biting midge species, Dasyhelea gongylophoda and Dasyhelea linlingae, were found back in 2005.

Leptanilla macauensis is tiny at under one millimetre long, with short antennae due to their subterranean nature. The naming of the species was recognised in 2018 by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, a global organisation for disseminating information on the correct use of the scientific names of animals. It made history because it meant Leong had become the first person from Macao who had named a new species from his own city – and it wasn’t Leong’s final discovery in the city. Also in 2018, he found two new orbatid mite species on that same small hill – Meristolohmannia macaoensis and Dimiodiogalumna ilhaverdeensis.

The service robot

It’s a truth almost universally accepted – robots are the future. The scientific study of robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) is seen by many as a crucial process in the development of the human race and the tools it has at its disposal. Robots can, in theory, serve almost limitless purposes for humans, from freeing up manpower and taking backbreaking work away from the poor to running mechanical operations more efficiently and effectively. Research into robotics is being done across the globe and in some robotic fields, Macao is at the forefront.

One of the companies breaking new ground is Singou Technology (Macau) Ltd, a local AI and robotics firm backed by the Macau University of Science and Technology (MUST). The team at Singou has created different types of service robots over the past few years. Its first invention was in 2017 – the ‘Singou Guard 1’, which incorporated the functions of facial and speech recognition with barcode scanning and video surveillance to create a robot that could be deployed for tasks like patrolling services, handling simple hotel customer enquiries and check-ins or marking attendances at meetings and exhibitions.

A year later, Singou improved its design and unveiled the ‘Singou Butler 1’, which came in a smaller size, boasting similar functions to its predecessor. However, this robot could be used in households and elderly care homes because it is additionally designed to perform cleaning tasks, measure blood pressures and call for the emergency services after detecting, for instance, a fall. A spokesman for Singou says: “Last year, the Singou team received commercial contracts to develop in-car social robots for several automotive companies in Mainland China. The in-car robot enhances the experience of interaction during driving.”

The revolutionary cancer treatment

A scientific discovery doesn’t necessarily mean an invention or the development of a piece of hardware. It can be the discovery of a new way of thinking or a new methodology. And it’s a particularly revolutionary discovery if it’s something that could significantly help millions of people to beat cancer in the coming years. Welcome to the work of Professor Chen Xin and Dr Joost J Oppenheim, two men dedicated to important cancer research.

Cancer is one of the leading causes of fatality worldwide, leading to about 9.6 million deaths a year or one in every six deaths globally, according to estimates by the World Health Organisation. In Macao, the proportion is even higher. Cancer is the most common cause of death in the city and accounts for about 35 per cent of its deaths. It’s no wonder, then, that scientists and medical experts in the SAR are searching for a cure. University of Macau scholar Prof Chen, however, may be moving us closer to one.

In 2018, Prof Chen, a professor at both the State Key Laboratory of Quality Research in Chinese Medicine (SKL-QRCM) and UM’s Institute of Chinese Medical Sciences, conducted an important study with Dr Oppenheim from the National Cancer Institute in the US. The study – which was featured in ‘The Scientist’, a globally influential professional magazine – focused on the role of ‘tumour necrosis factor receptor type II’ (TNFR2), which was long believed by the medical and scientific community to downregulate – a process of suppression – regulatory T lymphocytes (Treg cells or Tregs), meaning that TNFR2 was thought to decrease the function of Treg cells. That would be a good thing for any cancer patient, since the elimination of Treg cells is essential to cancer treatment as these cells could facilitate the growth and metastasis of a tumour.

But Prof Chen and Dr Oppenheim’s study – the first time that a scientific research study made in Macao has ever appeared in the pages of ‘The Scientist’ – challenged the traditional viewpoint of TNFR2. Together, they discovered that TNFR2 does not downregulate Treg cells but instead activates, expands and stabilises them. Basically, the doctors’ research had discovered that instead of promoting TNFR2, medical professionals should instead target it as that could help kill cancer cells. It was an important discovery that created a new theoretical framework in the treatment of cancer and has already led to the global pharmaceutical and medical community developing safer and more effective therapeutics against tumours.

“The significance of research like [ours],” says Prof Chen, “depends on whether it can have an impact upon the research and development initiatives of international pharmaceutical companies and whether it can be applied to the clinical treatment of patients. It’s not easy to do so but our discovery has gotten the attention of pharmaceutical companies worldwide.” Prof Chen, who joined the UM in 2014, adds that globally prominent laboratories like Harvard Medical School have already followed up on the research and he says that Swedish pharmaceutical firm Bioinvent revealed last year that it has been developing cancer treatments based on the anti-TNFR2 approach, saying it believes ‘targeting TNFR2 for cancer therapy holds great promise’. “We first found out about the role of TNFR2 in 2007,” says Prof Chen. “The result [we found] was completely the opposite to what academia believed at the time. There has been considerable success over the past 13 years in convincing most of the scientific community that TNFR2 should be targeted.”

The new TCM polysaccharides method

Boasting thousands of years of history, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has gained recognition and popularity beyond Chinese soil for its medical value in recent years. The World Health Organisation last year approved the inclusion of TCM for the first time in the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), an influential document that lists out thousands of diseases and medical diagnoses. As TCM is one of the emerging industries that Macao aims to nurture, the city has made significant progress in discoveries in the field to advance the development and internationalisation of the TCM industry.

A research team led by Professor Li Shaoping, deputy director of the SKL-QRCM at the UM, introduced in 2017 a new qualitative and quantitative method to determine the specificity of polysaccharides – carbohydrates whose molecules consist of a number of sugar molecules bonded together that are widely used in the development of commercial dietary supplements – after a decade of study. Due to the complexity of polysaccharides, it was previously difficult to assess their health benefits but the research by Prof Li’s team offers a simple way to do so. In short, polysaccharides are believed to have a number of benefits, including improving the function of the liver and adjusting the rhythm of the heart. Li’s study provides a usable method to assess the quality of polysaccharides in dietary supplements, thus helping to improve the development of these supplements. As a result, the team’s new methods have received multiple invention patents in Mainland China and have been applied to the quality evaluation of lingzhi mushroom dietary supplements in the US.

Prof Li and his team are not the only important TCM ‘discoverers’ in Macao. Another UM research team, led by Prof Lee Ming-Yuen, is also worthy of note. This team took nine years to extract a bioactive ingredient of the ‘PD-001 Molecule’ from Alpinia oxyphylla, a flowering plant in the ginger family that is a popular TCM ingredient. This extract from the plant could, it is hoped, significantly reduce the cellular damage in dopaminergic neurons in the brain that is believed to cause Parkinson’s disease, a condition that is famous for problems like shaking and stiffness that get worse over time. The discovery was made in 2018; however, Prof Lee’s work was less about discovering the extract and more about isolating it so that it can enter the food and nutrition supplement market.

The Ebola virus drug

With the current COVID-19 pandemic taking all the headlines, it’s easy to forgive anyone who forgets about Ebola. This severe, often fatal disease is still out there. In fact, just three days before the second largest Ebola outbreak, which started in 2018, was expected to be declared over, a new case was identified on 10 April when a 26-year-old died of the disease. Over the following days, five other people were identified as having Ebola, all in the Beni region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Ebola, which has claimed more than 10,000 lives in West Africa since 2014, is a virus that is transmitted to humans from wild animals and spreads through populations thanks to human-to-human transmission. The fatality rate is around 50 per cent of all cases. It’s been mostly prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa over the past few years but the threat of a pandemic is always there. However, researchers across the globe have been working overtime for years to find a vaccine or treatment. And one of these researchers is Faraz Mohammadali Shaikh, a doctoral student at the University of Macau’s Faculty of Science and Technology.

In August, Shaikh discovered two Ebola virus drug candidates. He screened a TCM-derived library of almost 2.5 million compounds on a computer against the Ebola glycoprotein and from that he identified eight candidates with potential inhibitory effects on Ebola’s infectious activities. Following that, two of the compounds were validated by collaborators from Oxford University in the UK – where Shaikh previously did a six-month internship – showing strong activity against viral entry. The discovery was then published in the ‘Journal of Medicinal Chemistry’.

For his work, Shaikh was awarded the Carl Storm International Diversity Fellowship, which sponsored him to attend the 2019 Computer-Aided Drug Design Gordon Research Seminar and Conference, in the US to present his findings. He was the only PhD student from an Asian university invited to speak at the seminar. There is currently no licensed treatment or vaccine for Ebola, so it is hoped that Shaikh’s discovery may pave the way for more research in the global mission to find one.

The revolutionary Moon theory

Macao may not seem like a hotbed of scientific activity when it comes to studies of the Moon. But it is – or at least it was last year when a group of scientists from MUST discovered something quite revolutionary about the evolution of Earth’s only natural satellite. In a paper published last May in the ‘Journal of Geophysical Research – Planets’, the team, led by Meng-Hua Zhu, suggested that our Moon, following its birth in a huge collision between the early Earth and a Mars-sized object, was hit by a second massive planetoid shortly after its formation. This would explain, claimed the team, why the Moon’s near side and far side are so different in terms of topology, composition and the thickness of their crusts.

The discovery made international headlines last summer, not least because the paper was published only a few months after China’s Chang’e 4 spacecraft became the first to land on the far side of the Moon. Of course, we never see the far side from the Earth because the Moon is tidally locked to our planet but thanks to NASA’s GRAIL mission to map lunar gravity, we now know the crust on the far side is up to 20 kilometres thicker than the crust on the near side. And the work by Zhu, an assistant professor at the State Key Laboratory in Lunar and Planetary Sciences at MUST, and his team has helped to explain the thicker crust on the far side, as well as helping scientists understand why the composition of the Moon is similar to Earth in some ways and in some ways not.

The team argued in the paper that the stark differences between the near and far sides could be the result of a ‘giant impactor’ slamming into the Moon and leaving a massive crater across the entire nearside. The researchers modelled 360 different collisions before suggesting that an object the size of the large asteroid Ceres, which is between 800 and 900 kilometres across, could have made the collision. The impact, claimed the scientists, could have left a crater stretching 5,600 kilometres across the moon’s surface, which would essentially cover the entire near side.

The effects of this discovery could be far-reaching and could displace other theories, including the idea that the Earth originally had two smaller moons which collided to form the Moon we see today. Describing Prof Zhu’s discovery – which was made in collaboration with colleagues in the US, France and Germany – as making ‘major breakthroughs in the field of lunar evolution history’, a spokesman from MUST following the release of the paper said this discovery could help provide more theoretical and scientific support for future missions to the Moon. For a small city in a small area, Macao is frequently astronomically effective when it comes to scientific research and discoveries.