Built some time before 1892, the restoration of the pharmacy was a long and difficult job for the Cultural Affairs Bureau, after the Macao government acquired the property in 2011.

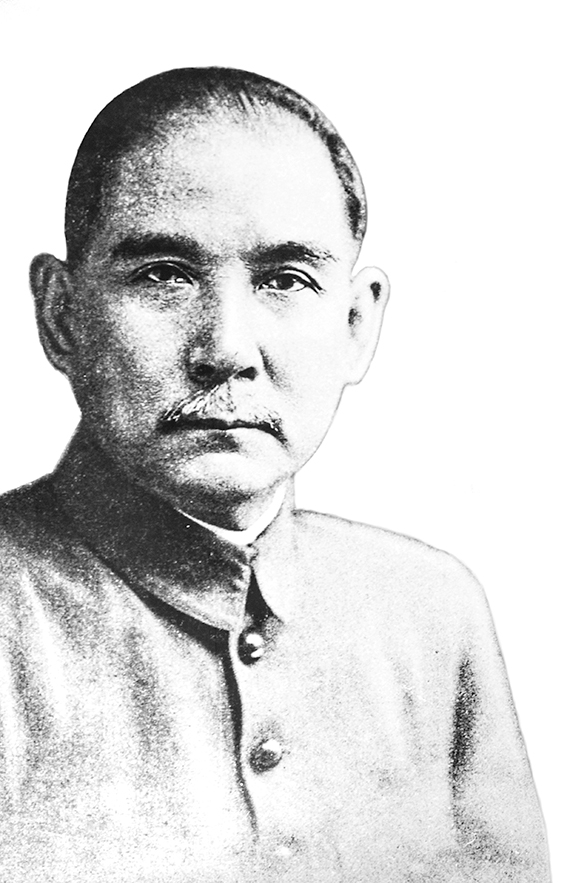

Down a narrow street in the heart of old Macao is a sparkling shop, recently restored to its former glory after years of disuse. This is the Chong Sai (Chinese and Western) Pharmacy, which, more than a century ago, belonged to Dr Sun Yat‐sen, the father of modern China.

Acquired by the government of Macao in 2011, the property underwent a painstaking restoration at a cost of MOP14 million (US$1.74 million) before opening to the public on 15 December 2016, the 150th anniversary of Sun’s birth. The property is one of 10 that the Cultural Affairs Bureau (IC) began assessing for potential cultural value in 2015. It received classification and protection as a monument just last year. Located at 80 Rua das Estalagens, the shop sat on one of three streets that formed the commercial heart of the city in the early 20th century.

The three‐storey former shophouse now serves as a museum space, with sections on archaeological artefacts and traces, renovation techniques of the building and architectural features, as well as a section dedicated to Dr Sun Yat‐sen and Macao.

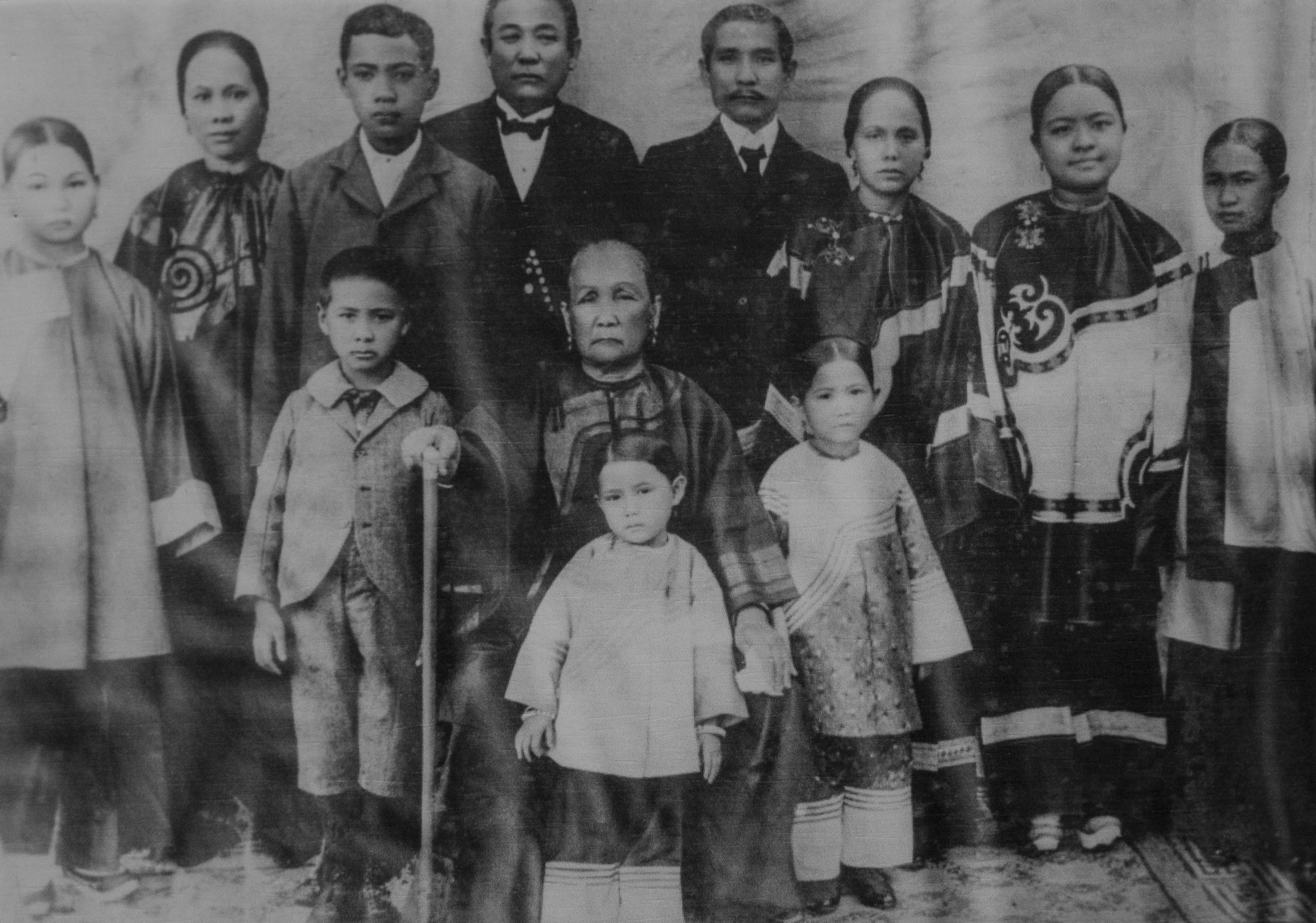

The exhibits offer a vivid impression of Sun’s brief medical practice in Macao between autumn 1892 and September 1893, and the city’s deep links with him, his family, and his republican mission. Macao served as a base of his revolutionary party and became the permanent home of his elder brother and Sun’s first wife, Lu Muzhen, and along with their children.

Lu lived here until her death on 7 September 1952, at the age of 85. Six years later, in 1958, the family home became the Sun Yat‐sen Memorial House.

“When [Sun] was studying Western medicine in Hong Kong, Chinese businessmen in Macao invited him to come here and treat their friends,” said Harold Kuan Chon Hong, a senior technician in the IC’s Department of Cultural Heritage. “That is why he came here after his graduation. He was the first Chinese in Macao to practice Western medicine.”

Initially, Sun worked at the Kiang Wu Hospital. The museum includes photographs of the hospital when it was built in 1871 to serve the Chinese population of the city. Sun went on to open two clinics: one at Largo do Senado and one in this restored building.

“The name [Chong Sai] is interesting,” Kuan remarked. “It tells us that Sun dispensed both Western and Chinese medicine. He was the only Chinese doctor in Macao who did this.”

But the Portuguese doctors of Western medicine refused to work with Sun. “They did not welcome him and would not cooperate with him,” said Kuan. The records do not tell us what spurred this hostility, but it was severe enough that Sun was forced to move his medical practice to Guangzhou in late 1893.

A recurring theme

Macao played an important role in Sun’s life. His father, Sun Dacheng, a landless farmer, worked here for 16 years as a shoemaker between 1829 and 1845 before returning home to Cuiheng village in neighbouring Xiangshan (now Zhongshan) county, 27 kilometres away, to marry and start a family.

There, he farmed land rented from others and worked as a night watchman to earn extra money. Sun was born on 12 November 1866, the fifth of six children.

In 1871, Sun’s elder brother Sun Mei, then 17 years old, followed an uncle to Hawaii to escape poverty and make a better life. He started as a hired labourer but eventually became a prosperous cattle rancher and store owner, famous in the community.

He invited his younger brother, then just 13 years old, to join him in 1878. The next year, mother and son passed through Macao on their way to Hong Kong, where they took a British steamship for Hawaii. There he studied math, science, British history, English, and Christianity at ‘Iolani School and briefly attended Oahu College (now Punahou School) before returning to home in 1883.

He brought with him the village’s first kerosene lamp – and a certain disdain for traditional religion after years of Christian schooling. When he and a fellow student destroyed the statue of a traditional deity, which they regarded as an image of superstition, the villagers were furious. Sun’s father had no choice but to send him to Hong Kong, where he continued his education at the Diocesan Boys’ School.

Sun went on to study medicine at Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese (forerunner to the University of Hong Kong), of which he was one of the first two graduates in 1892. He returned home only briefly, in 1885, to marry Lu Muzhen, the daughter of a Chinese merchant in Hawaii; it was a marriage arranged by the two families, which was the custom at that time.

As a student, Sun was in Hong Kong with a group of revolutionary thinkers nicknamed the Four Bandits, holding meetings and writing tracts against the decay and corruption of the Qing government.

He also became friends with a Portuguese named Francisco Hermenegildo Fernandes, who worked as an interpreter at a court in Hong Kong. The two reunited in Macao in 1893, Fernandes having returned to work in the family business. Sun, upon graduating the previous year, had left Hong Kong in search of a place where he could practice medicine.

Fernandes proved a beneficial ally in his new home in Macao. After founding Echo Macaense, the city’s first weekly bilingual newspaper, in July 1893, Fernandes used his platform to promote Sun both as a physician and a critical political thinker.

It wasn’t enough, though. Facing resistance and hostility from the medical community in Macao, Sun left the city to practice in Guangzhou. After taking part in a failed uprising in Guangzhou in 1895, Sun fled back to Macao. “It was Fernandes that sheltered him and helped him to flee to Japan,” Kuan noted. A photograph of the Portuguese publisher appears in the museum’s collection.

“The Qing government asked the colonial authorities to arrest Sun,” said Kuan. “They did not refuse the request but did not actively seek him. They were passive. This helped him.”

On 29 March 1925, 20,000 people in Macao – one‐fifth of its population – attended a memorial service at Kiang Wu Hospital.

Over the next 16 years, Sun led more than a dozen attempts at overthrowing the Qing government before succeeding in 1911. In January 1912, Sun became president of the new Republic, a position he held for less than three months due to Yuan Shikai, the most powerful military leader in China at the time, taking over in March.

Before his death in 1925, Sun made a few trips to Macao to visit with family and supporters. A photograph from his visit in May 1912, a few months after his short‐ ‐lived presidency, shows the large group of Macao businessmen who gathered to welcome him.

Sun spent the last years of his life once again taking up the cause of revolution as the fledgeling republic descended into the so-called Warlord Era, marked by multiple military factions vying for control from their regional strongholds.

Despite his failing health, he continued to travel and give speeches outlining his vision for China’s future. Dr Sun Yat‐sen died on 12 March 1925 in a Beijing hospital where he was being treated for liver cancer. He was 58 years old.

On 29 March that year, 20,000 people in Macao – one‐fifth of its population – attended a memorial service at Kiang Wu Hospital. A statue of him now stands there in his honour.

Painstaking process of restoration

The restoration of the pharmacy was a long and difficult job for the IC, after the Macao government acquired the property in 2011. Built some time before 1892, when Chong Sai Pharmacy was established it belonged to Tso Yau, a prominent local businessman and founding council member of the Kiang Wu Hospital.

The building is a typical traditional three‐storey Chinese shophouse, with a business space on the ground floor and living quarters on the upper floors. Composed of three halls on a front‐to‐back axis, separated by two enclosed courtyards and connected by side corridors, it has an area measuring 525 sq metres on a narrow 188‐sq metre tract of land.

After Dr Sun left for Guangzhou, the building was rented and sold several times and used as a Taoist hall. From the 1930s, it was primarily used for the textiles business and later leased to an electrical appliance store.

By the time the government of Macao acquired it, the building had been abandoned for years. The IC had to repair the roof, to stabilise the structure, kicking off a search for the appropriate materials. Their commitment to using original materials meant that, rather than buying wholesale construction materials, the IC had to go to sites where old buildings were being demolished and salvage what they needed. It was the same with the damaged wooden beams and fir slabs.

Then they ran into an entirely new problem. Excavation revealed material below the building that archaeologists believe had been part of the early coastline of Macao. Recognising the historical value, the IC altered their restoration plans to integrate the archaeological discovery into the museum experience. A railed opening allows visitors to see the exposed stone structure beneath the shophouse floor.

The narrowness of the building, typical of shophouses, and lack of side access also complicated the renovation process. While the IC took great pains to preserve the historic building, they did make some concessions to modernity. A lift, staircase, and toilet were added at the rear for the convenience of the public.

The beautifully restored structure now offers visitors a glimpse of the city’s ever-changing coastline and invites them to explore the traditional shophouses that once populated the heart of Macao. It also tells the story of the city’s connection to Dr Sun Yat‐sen, a man of humble beginnings whose vision and unwavering dedication gave rise to modern China.