TEXT João Guedes

The story of Macao’s José d’Almeida Carvalho e Silva: Doctor, Scientist, Revolutionary

Of all the major political changes that occurred in Portugal, none impacted Macao more intensely than the Liberal Revolution of 1820. Its brutal repercussions affected the Portuguese colony nearly two years later, when the news finally reached its shores via sailors.

Shortly after the first oaths to the first Portuguese constitution, Macao entered a state of real political and social upheaval. The Governor and Ouvidor (the magistrate responsible for just about everything in the colony) were both arrested; the members of the Loyal Senate were removed and others, with a liberal bent, elected in their place. The same happened across other official civilian and military institutions. Also, ties binding Macao to Goa were cut and for nearly a year Macao thrived as an independent, democratic republic that only ‘formally’ declared fealty to Lisbon.

This situation lasted until the arrival of a military force sent by the Viceroy of Portuguese India, Dom Manuel da Câmara. A supporter of the absolutist King Miguel, he dislodged and arrested the main revolutionary leaders. This stroke from the resurgent ancien régime decapitated the leadership in almost all of Macao’s civil and military departments, with the enclave’s intellectual elite choosing to flee or face capture.

Among the imprisoned leaders was Dr José d’Almeida Carvalho e Silva, the Director of St Rapahel’s Hospital, at the time Macao’s only health establishment, located in the building which now houses the Consulate‑General of Portugal.

Other jailed revolutionaries included the Rector of St. Joseph’s Seminary; Father Pinto e Maia, the President of the Loyal Senate; Colonel Paulino Barboso, his comrade in arms António de Holanda Cavalcanti (who would later serve as Minister in various governments of Brazil), and Priest António de São Gonçalo de Amarante; Editor of the first Portuguese newspaper in the Far East. Together they were put in irons and sent to Goa for trial.

However, upon their arrival, the shifting political situation enabled the majority to escape to the British city of Calcutta, where they were, at least provisionally, beyond the reach of the Viceroy’s justice.

Exiled and living in fear of imprisonment, d’Almeida was presented with an opportunity by British adventurer Stanford Raffles that he could not refuse.

Then in Calcutta, Raffles had just recruited Major William Farquhar to be the military chief of his project to found a colony at the mouth of the Singapore River in Malaya. However, he also needed someone to take care of organising health services. Singapore was situated in an area of low water and swamps that exposed it to various diseases, especially dengue and malaria; therefore public health would be a top priority.

D’Almeida quickly accepted the offer, as Singapore was not unknown to him. During his various voyages in Southeast Asia as a naval physician, he had landed several times in the incipient colony, buying a few plots of land that were then on sale at tempting prices. At the time, trade between Macao and the ports of Malaya and Indochina was intense and there were also regular maritime links with Portuguese‑owned Timor and Flores in the East Indies. And so, under British protection, d’Almeida embarked on a new journey to the Far East, to settle in the new English colony.

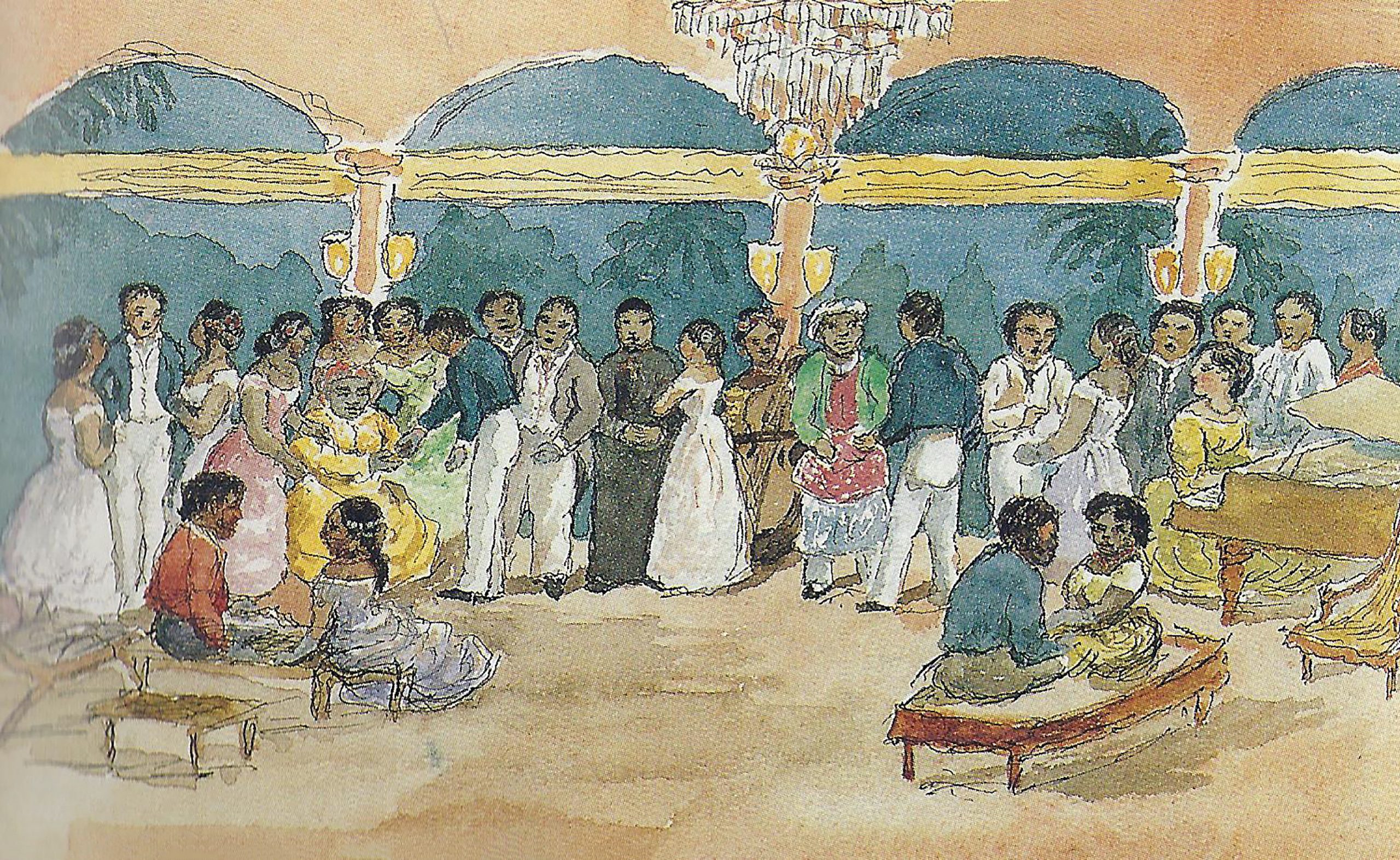

Upon arriving, d’Almeida set up his clinic near the shore on Beach Road; now known as Raffles Place, building his home a short distance away. This large mansion would become known as a meeting place for Singapore’s best artists and musicians and d’Almeida became renowned for his fabulous soirées, even directing plays in his home that would often star many of his 20 sons and daughters. These events would regularly be recorded for prosperity in the form of paintings and illustrations, which were often featured in the newspapers of English India.

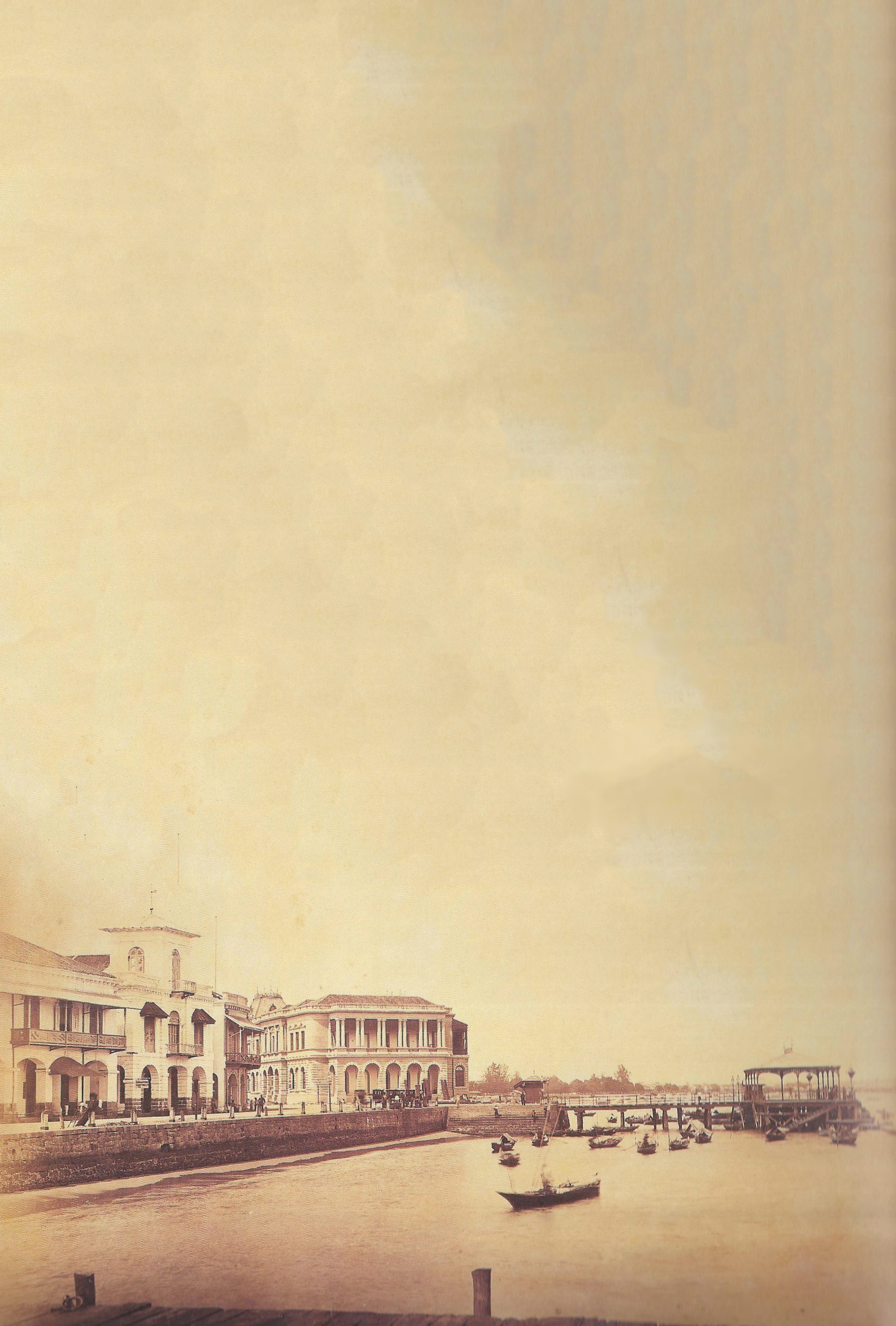

Alongside hosting famous parties and developing Singapore’s early healthcare infrastructure, d’Almeida also devoted time to general trade, creating the firm of Almeida and Sons.

The company had its own private quay, eventually opening branches throughout the region, including Macao, and extending as far as distant Germany, where one of his sons went on to settle. However, d’Almeida found that running the business took time away from his true passions for science and medicine, and he eventually handed over commercial management of the business to his eldest sons Joaquim and José.

This freed up his time for scientific study, with botany becoming his field of choice. D’Almeida began research of the Gutta‑percha tree with another reputed scientist, William Montgomerie, who had arrived in Singapore in 1819 as a military surgeon. But, like his Portuguese colleague, his activities extended far beyond medicine; at one point, he held the roles of Magistrate and even Sheriff of Singapore.

Together the scientists initiated what would later become Singapore’s botanical garden, located in a swampy area of the city. Gradually drained and propagated with new species, in 2015 it was recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The two scientists’ work focused on the capacity for industrial use of gutta‑percha latex, due to its elastic properties. Their experiments led to the early discovery that it could be applied in surgery, specifically for dental moulding and filling. This work led Montgomerie to India, where the latex was registered with Calcutta Medical Board.

Even though it was developed for surgical medicine, its first application was actually in the telecommunications industry, used to insulate underwater telegraph cables laid by England for the first time in 1845. Later it was used in the manufacture of golf balls.

The Gutta‑percha latex’s industrial use declined with the further development of plastics and synthetic resins, however, it is still used today in dentistry, helping to seal dental canals and prevent infection.

As was the fashion of that time, D’Almeida’s experiments also included crossing species in order to test their possibly industrial use. Among others, he experimented with vanilla, cloves and the cochineal, in addition to devoting time to the import of birds, namely quail. All these species can be still seen today in the city‑state’s botanical garden, including a banana‑tree species that resulted from his cross‑breeding. The pisang d’Almeida, (d’Almeida banana) is now cultivated across Southeast Asia.

Sadly, the public figure of D’Almeida was long left in historical oblivion. His progressive political outlook put him at odds with the Catholic Church, even though he had actively worked with Father Pinto Maia to further its establishment and consolidation in Singapore. Therefore, subsequent ecclesiastical biographers did what they could to downplay his figure.

However, during his time he did obtain due recognition. He was decorated with the Order of Christ by Portugal, raised to the title of Counsellor of Queen Maria II and named Consul‑General of the Straits; the region extending from Malacca to Singapore.

The services he rendered to Spain likewise earned him the title of Knight of the Order of Carlos III, while Great Britain granted him the honorific of Sir, the only foreign title recognised in Singapore.

Therefore, it is not surprising that on his death on 27 October 1850, there was an outpouring of grief unprecedented in Singapore’s history, with the city‑state’s most prominent figures from all ethnic groups, along with all other citizens able to make the journey, attending his burial ceremony at the Catholic cemetery of Fort Canning.