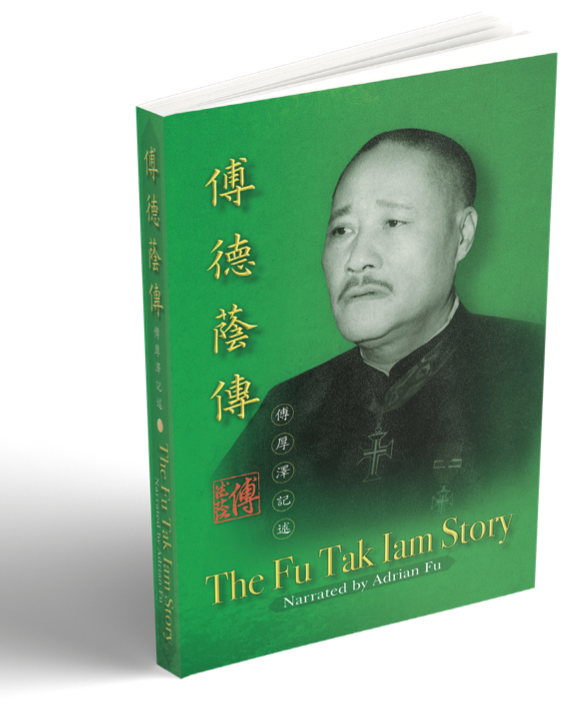

Adrian Fu depicted the story of Fu Tak Iam, his grandfather and Macao’s former gambling mogul, in a vivid bilingual biography.

In January 2019, Adrian Fu published a biography of his grandfather, Fu Tak Iam, whose company held the gambling franchise in Macao between 1937 and 1961, and who laid the foundation for his family’s business empire today.

“This book took three years to write,” said Fu in an interview in Hong Kong, where he lives. “My father died 13 years ago and I saw the many documents Grandfather left behind about his life. I learnt much I did not know.

“He spoke little and did not like to socialise. But each week he wrote letters, to his children, grandson, and business associates.” Fu had four wives, eight sons and seven daughters; Adrian’s father was the eldest son.

These letters proved a treasure trove of information about Fu’s life, family, and businesses. Adrian hired two mainland professors to study them and conduct supplementary research in Macao, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the mainland.

“The book is being published by our Fu Tak Iam Foundation with 2,000 copies in English and Chinese in the first printing,” he said. Adrian has registered his second foundation in Macao and plans to turn two houses here into a memorial for his grandfather, available for use by the foundation and other local NGOs. Such a move will require approval by the Macao government.

Cutting wood to Casino City

The story of Fu Tak Iam’s rise from rags to riches is the stuff of Hollywood films. Born in 1895 to a poor farming family in a village in Nanhai county, Foshan in Guangdong province, Fu had little formal schooling. He was eight years old when drought forced his father to leave the village for Hong Kong where he worked in a metal shop. Fu himself began working at an early age, first collecting and selling firewood to help support his family.

He made the journey to Hong Kong in 1908, just 14 years old, to help his father in the shop. Three years later, he took a job as a stoker in the boiler room of a British vessel, working a route between Hong Kong, Macao, Guangzhou, and ports in the Pearl River Delta.

“It was exhausting and dangerous work,” said Adrian. Fu used the two and a half years he spent with the company learning about mechanical engineering, but even then, gambling had already caught his fancy. He often spent his spare time wandering the streets and gambling when he could. One day, Fu was gambling in Central (Hong Kong) and got arrested after getting into a fight. “His father was very anxious about him.”

Sentenced to 10 months in prison, Fu made best use of the time in jail and learned much about gambling from the other inmates.

After leaving prison, Fu moved to cities in Guangdong and Guangxi and went into business: opium, gambling and firearms, all profitable sectors. He returned to Hong Kong flush with cash from his many ventures. While horse racing was the only legal form of gambling there, local governments in China turned a blind eye.

Fu met Huo Zhi-ting, president of the Guangdong Bank and founder of the Hong Nin Savings Bank of Hong Kong, in the early 1930s. Despite Fu losing out on his bid for the gambling franchise in Macao to Huo’s consortium, the two became friends. Huo admired Fu’s management of gambling and agreed to fund a large casino in Shenzhen aimed at punters from Hong Kong. Huo had the support of Chen Jitang, a warlord powerful in Guangdong.

There Fu built the largest casino in China, involving an investment of 10 million yuan. It attracted many gamblers from Hong Kong, just as intended, and badly affected the casinos of Macao. But in 1937, after Japan launched its all-out war on China, the Nationalist government banned gambling on the mainland. The Shenzhen casino was forced to close, resulting in heavy losses for its investors.

Winning Macao franchise

Fu returned to Macao just in time to make a second attempt at the franchise in the city. He partnered with Kou Ho-neng, who had made a fortune from a chain of pawnshops, to form the Tai Heng company. Their bid of 1.8 million patacas a year won in 1937; they promised three casinos, the largest in the newly renamed Hotel Central in downtown Macao.

Tai Heng would hold the gambling monopoly for the next 24 years. Their bid turned out to be an excellent investment, especially during World War II, when Macao was the only city in East Asia not under Japanese military occupation.

Thousands of wealthy people from Hong Kong, the mainland, and overseas took refuge there to escape the war. Japanese business people, officials, and military officers were also frequent visitors to the Hotel Central , patronising its bars and restaurants and the other casinos. There was little alternative entertainment. Fu used the profits to invest in passenger ships, the Number 16 pier, and trading.

After the fall of Hong Kong in December 1941, thousands of refugees flooded into the city, joining those from the mainland. The city struggled to cope, its population ballooning to around 700,000, more than four times what it was before the war. Food, medicine, and shelter were in short supply, leaving hundreds to die of starvation on the streets.

“During World War II, Grandfather did everything,” said Adrian. “He gave money to buy rice for the refugees. He also had a rice mill to provide a staple diet for them.

“He did not sleep at night. He stayed up until all the cash from the casinos had been collected and safely stored. He would sleep at four or five in the morning and get up at midday. He did not drink but smoked opium every day. He believed it was good for his health.”

Fu kept the Japanese officials at a distance, dealing with them indirectly through representatives. While technically unoccupied, Macao was hardly free from Japanese interference during the war.

Danger of wealth

Despite being one of the wealthiest men in Macao, Fu did not fear for his safety and usually had only one bodyguard. On 10 February 1948, he went into the Kun Iam Temple, leaving his driver outside. A group of armed men burst in and kidnapped him. They demanded a ransom of nine million Hong Kong dollars.

“They did not beat him up,” said Adrian. “He did not fear the kidnappers. They were people like him. He knew what they were like.”

The family turned to Ho Yin, a highly influential Chinese and colleague of Fu’s, to mediate negotiations for his release. With his help, the two sides agreed to a much-reduced ransom of 900,000 Hong Kong dollars, but when one of Fu’s children brought in the police, the deal fell apart.

Enraged, the kidnappers cut off the top of Fu’s right ear and sent it to his family as a warning. They also reverted to their original ransom demand, prompting the family to reach out to another mediator: the famous Cantonese opera star, Tang Wing Cheung. He got the ransom back down to 900,000 Hong Kong dollars; the family paid and Fu was released. Police eventually arrested a renegade Kuomintang soldier believed to be the ringleader; he was sentenced to 18 years in prison.

While unscathed psychologically, the experience did lead Fu to increase his own security: “From then on he carried a gun and was accompanied by two bodyguards.”

After World War II, Fu diversified his investments in Hong Kong, moving into property, shipping, construction, cinemas, and trading. He decided that the next generation should not follow him in the casino business; Adrian’s father had no interest in the sector. He was sent to Hong Kong in 1946 to set up an office there, establishing Kwong Hing Investment (KHI) Holdings the following year.

Preserving the family legacy

Fu was a workaholic, with little time for his four wives and 15 children, and little interest in socialising. He spoke little; his main method of communication was letters, which he wrote each week, to his children and employees, mostly with instructions on what to do.

“He was meticulous in his work, with detailed plans. He set up a company and made his sons the shareholders; his daughters did not go into the business. There was enormous pressure on my father as the oldest son who had to look after and educate his siblings,” Adrian explained. “Grandfather talked little to his children. My father both feared and respected him.”

Adrian was born in 1947. He attended schools in Hong Kong and visited his grandfather in Macao at Chinese New Year and during the school holidays. “He was kind to me. He talked to me and I listened,” Adrian reflected. Fu died in 1960 after a period of declining health; he was 65 years old.

Adrian’s father, Fu Yum Chiu, also established the Tak Kee Shipping & Trading Company in Hong Kong in 1947, diversifying early on into property development. The Furama Hotel stands as the flagship property development for the company, now part of KHI Holdings Group, which oversaw construction and management of the hotel. Opened in 1973, the property set a new standard for business hotels in Asia and yielded significant returns for investors when KHI exited in 1997.

The company remains family-owned, with Adrian Fu serving as the current chief executive. Under his leadership the company has held to the core values established by his father, emphasising conservatively managed growth and diversification.

Adrian also seeks to perpetuate his family’s legacy through the foundation named for his grandfather. Their work centres on two values: eliminating social injustice and prejudice through education, and improving the quality of life for those who are deprived. For Adrian, the foundation is “the most meaningful interpretation of my father’s love and respect for my grandfather” as well as “an effective tool to communicate our family history to future generations.”

Those in Macao interested in learning more about Fu Tak Iam can visit his former home, located at 28-34 Avenida da Republica and owned by the Fu Tak Yung Foundation, and read two marble tablets about his life housed in two pavilions on the property. Or they might pop over to the pavilion in Chong San Memorial Park on Guia Hill to read the tablet there.

For those looking to dive deeper into the biography of the gambling mogul, they can read the The Fu Tak Iam Story (踧德蔭頦), published by his namesake foundation.