“A woman without talent is virtuous.” This feudal saying from the Ming dynasty is shocking today, but raised few eyebrows a century ago. It wasn’t until the early 1900s that foot binding – a painful form of female suppression – began to die out in China. Foot binding was fought against by Christian missionaries and Chinese reformists. One of the latter was Zhang Shoubo, later known as Master Guanben. He is one of the key figures in this story.

In 1924, Master Guanben established the Kong Tac Lam Temple – Macao’s first Buddhist college for women. Located at a quiet intersection near Senado Square, the college also served as a safe harbour for monks and intellectuals fleeing the mainland during World Wars I and II. Over the decades, as more opportunities for women emerged, the temple’s role has evolved. It’s been a place for monks (of any gender) to study and practise Buddhism since the 1980s. Master Guanben died in 1946.

In May this year, the temple’s extraordinary collection of manuscripts, rare books, scriptures, photos, paintings, and letters – known as the Kong Tac Lam Temple archives – was inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of World Register. The archives’ oldest entry is Buddhist scriptures dating back to 1645.

The more than 6,000 pieces of archival material were accumulated by Master Guanben during his own extensive travels, as well as by other thought leaders associated with the temple. Many of these esteemed men and women were directly involved in raising the social status of women in Macao, the mainland, and beyond.

A scholar’s encounter

Helen Ieong Hoi Keng is the other key figure. She is the woman behind Kong Tac Lam Temple’s UNESCO status, as well as Master Guanben’s recognition as an advocate of early feminism. Now president of the Macau Documentation and Information Society, Ieong has spent decades working intimately with the territory’s archival documents. It was during her doctoral thesis (on the written records shaping Macao’s unique characteristics) in the early 2000s that Ieong first encountered the temple’s trove of material.

She was studying records kept by Macao’s Catholic Dioceses at the time, and realised it would be interesting to compare them with historical documents from another religion. Having heard about old volumes of Buddhist scripture being kept in the Kong Tac Lam Temple, Ieong sought permission from the current abbot, Master Jiecheng, to examine them. He willingly granted her access.

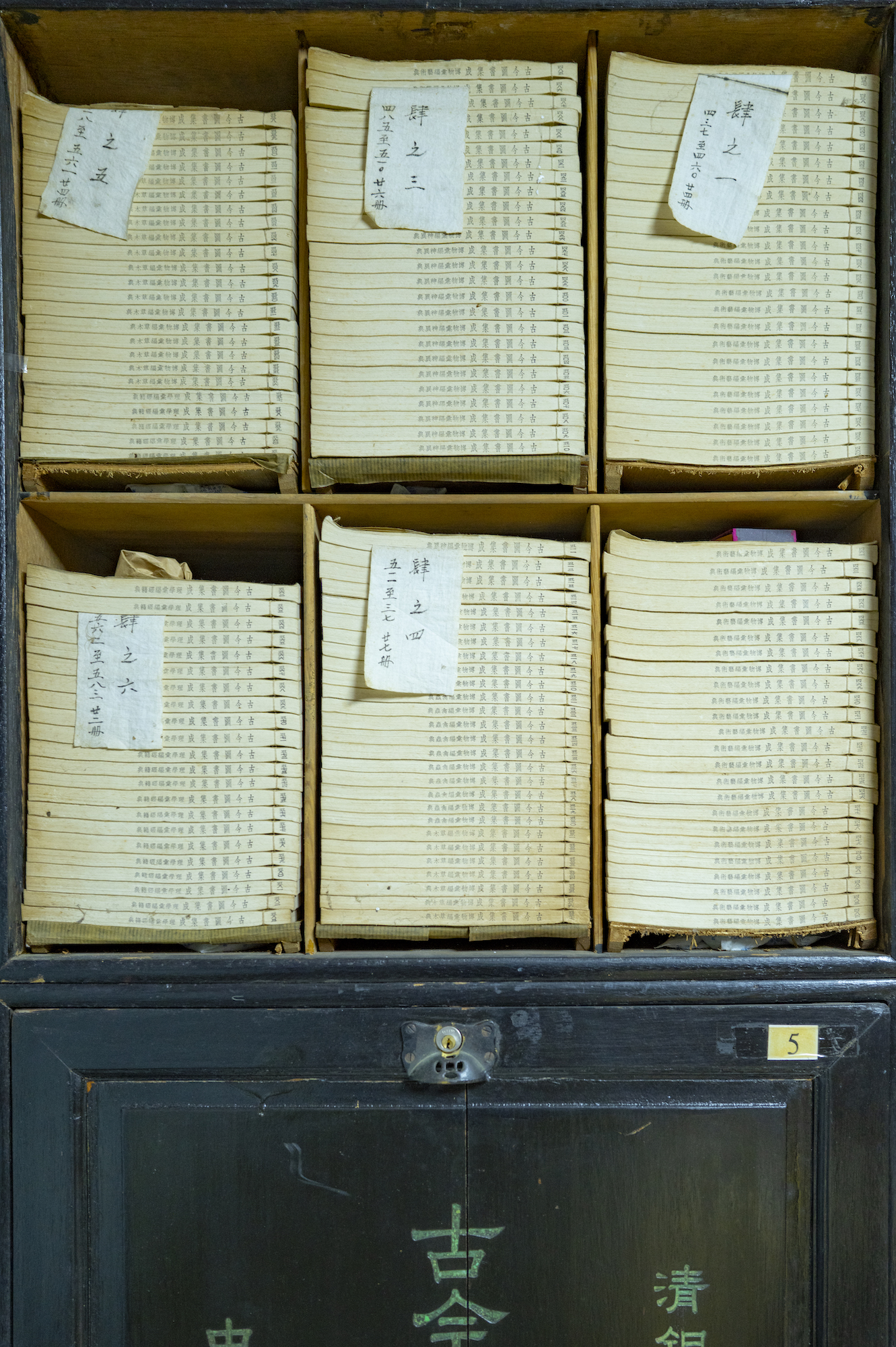

“When I went to the shelves of books, they were arranged very neatly, but without any serial numbers,” Ieong recalls. “I took a long time to peruse them and [it turned out] they were invaluable pieces.”

She says the discovery was a “happy surprise”. Until then, the archivist had associated temples with religious rituals – not written records that related to her work.

Master Jiecheng allowed Ieong to spend as much time as she liked with the archives. “He was very open-minded and allowed me to study them,” she describes. Before long, she found herself on a mission: to get the Kong Tac Lam archives inscribed on the Memory of World Register for Asia-Pacific.

Before making the application to UNESCO, with the help of the temple’s monks, Ieong and her team of three archival experts spent years sorting out the thousands of incredibly rare and unique documents. They arranged them into 10 categories, including general theories, doctrines, history, scriptures, and Chinese and global Buddhist lineages. They also created serial numbers for everything they archived, noting publication years and locations when possible.

While the team uncovered a great many valuable religious texts, Ieong decided to base her application from the perspective of women’s liberation.

“Due to the efforts of intellectuals, like Master Guanben, involved with the Kong Tac Lam Temple, women’s social status could be elevated,” is how Ieong explains her decision.

The Kong Tac Lam Temple archives were inscribed into the Memory of the World Register for Asia-Pacific in 2016 for its outstanding regional value. Since then, UNESCO has deemed the archives qualified to meet the higher bar of outstanding global value.

Master Guanben: becoming a Buddhist and founding a school

Zhang Shoubo was born in Xiangshan County (now known as Zhongshan County), Guangdong Province, in the late 1860s. An educated man, Zhang moved to Macao in 1894 and set about disseminating reformist ideas. He started clubs where people could learn to read Chinese and speak foreign languages; he taught public speaking and publishing. Zhang also encouraged Macao people to stop smoking opium (a major scourge at the time) and, notably, cease the ancient practice of binding women’s feet.

He was deeply influenced by progressive intellectuals of the time, including Liang Qichao, Zheng Guanying, and Kang Youwei (who founded the Foot Emancipation Society in 1887). These men played leading roles in women’s liberation and the Hundred Days’ Reform of 1898. Zhang counted them as his personal friends.

Life threw some curveballs at Zhang, which is how he became involved in Buddhism. When the Hundred Days’ Reform (a bid to modernise China’s political, educational, and military systems) failed, and his own attempts at running a business foundered – Zhang sought a more spiritual path. He became a Buddhist monk in 1914 and changed his name to Master Guanben.

Ten years later, Master Guanben transformed his own home into the Kong Tac Lam Temple and began admitting female students of Buddhism. “He wanted to establish a place to disseminate Buddhist teachings and promote women’s social status,” says Ieong, who has written a biography on Master Guanben. She suggests his interest in women’s rights stemmed from the fact there were an unusually large number of females in his family.

“There were always many women around him, including his mothers [Master Guanben grew up with both a birth mother and an adopted mother], two wives and several daughters. It meant he could think in their shoes.”

The temple also blended Buddhist principles with Confucian and Taoist thought, which both express high regard for maternal figures. Ieong believes these ideas contributed to Master Guanben’s interest in advancing women’s social status.

About 50 students lived at the spacious temple, along with Master Guanben and his family. Ieong says classes followed strict rules. She has read the original prospectus, which states that students must abstain from meat and avoid quarrelling with their classmates. No women who’d run away from home would be admitted.

Lessons mostly focussed on Buddhist teachings, though the women were also taught needlework and how to use an abacus for calculations. Aside from studying, there was housework. Ieong says schedules could be arduous. “They had to get up at 5 am and ring the morning bell, but there were different schedules for different times,” she says. “I once interviewed Master Wenzheng [a former abbot of the temple]; he told me they had to get up at 3:30 am.”

Each student was given 100 patacas to help support their family, allowing them to fully focus on studies. The temple was financially supported by many Buddhist followers, as well as prominent socialists who donated to the cause. Two supporters of note were businessman Chien Chao-nan – founder of the Nanyang Brothers Cigarettes Company and a relative of Master Guanben – and Lady Clara Cheung, the wife of businessman and philanthropist Sir Robert Ho Tung.

Lady Clara was an avid recruiter of female students for the temple. She also invited many renowned Buddhist monks to give talks at Kong Tac Lam, as well as at her mansion – now known as the Sir Robert Ho Tung Library – in São Lourenço.

Documenting friendships and history

Letters between the reformist Liang Qichao and Master Guanben are an important part of the Kong Tac Lam Temple archives. Ieong discovered them wrapped in old newspapers; even Liang’s granddaughter didn’t know of their existence, she says.

The earliest evidence of Liang and Master Guaben’s acquaintance is a petition signed during the 1895 Gongche Shangshu movement (a precursor to the Hundred Days’ Reform). Liang submitted this petition to Guangxu’s Emperor, urging him to stop China signing the Treaty of Shimonoseki with Japan. This was one of several unequal treaties imposed upon China during the late Qing dynasty,

which ultimately weakened its position in global affairs and sparked internal division. Liang’s name topped the list of scholars signing the petition; Master Guanben’s was number eight.

When the Hundred Days Reform failed in China, authorities from the Qing dynasty tried to kill Liang. Along with many other Chinese reformists at the time, he escaped to Japan. While there, Liang organised Chinese schools for his fellow émigrés’ children. In the Kong Tac Lam archives, an undated letter from Liang invites Master Guanben to visit Japan and help him run the Chinese schools there. Master Guanben heeded the call, spending time as principal at a Chinese school in Kobe before establishing Kong Tac Lam Temple in Macao.

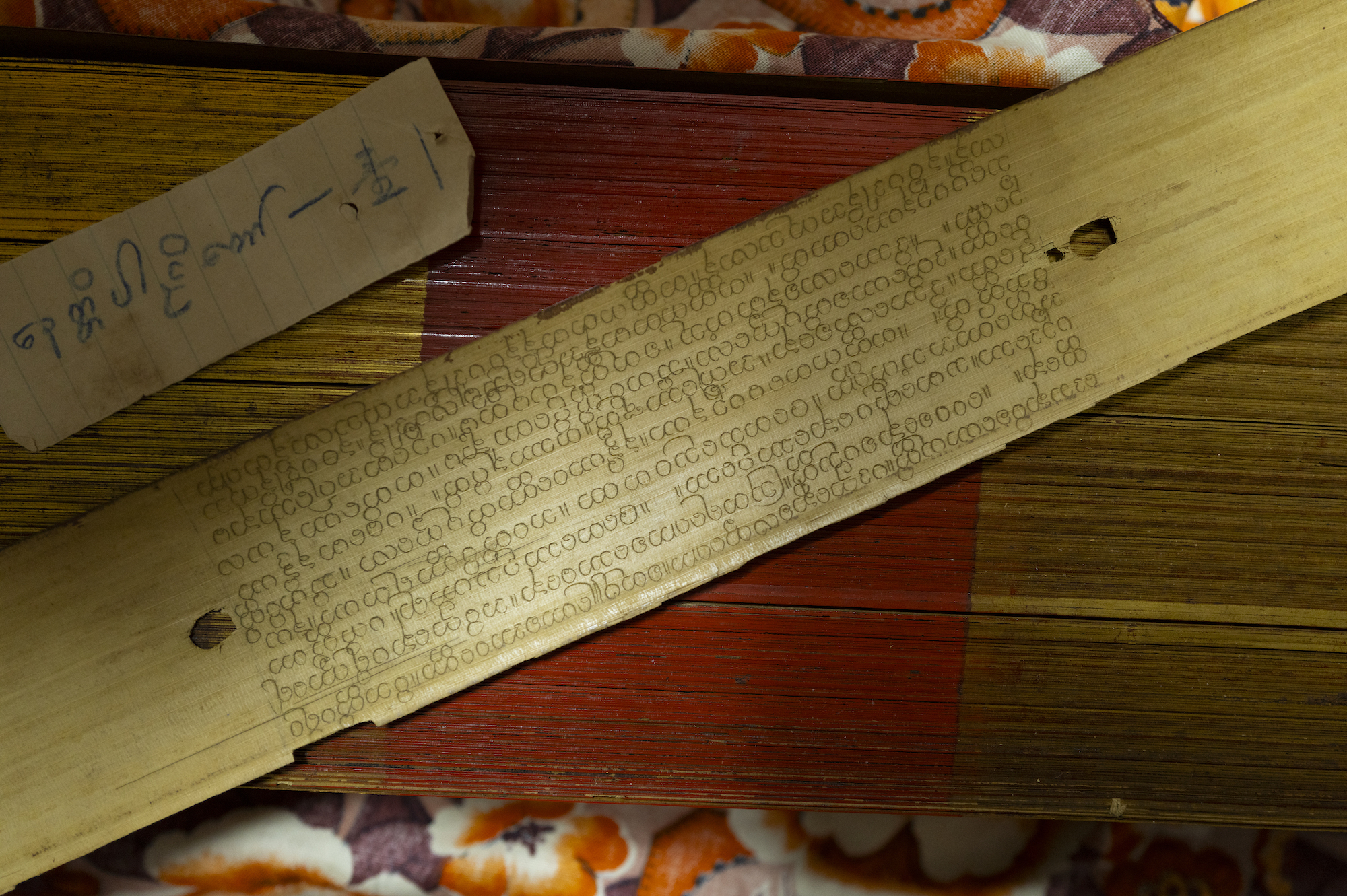

Buddhist scriptures inscribed on palm leaves are another of the archives’ treasures. These were written by monks on palm bark, likely in Burma, says Ieong. No one is sure when. To make these scriptures, which Ieong says are now worth a fortune, monks softened the bark by steaming it then inscribed their words using a knife. They’d use charcoal to darken the inscriptions. Both ends of the crispy bark strips are gilded, to prevent peeling.

“Master Jiecheng told me about these scriptures,” says Ieong. “He didn’t know why they turned out to be here [at the temple]. Perhaps they were brought to Macao when Master Guanben travelled around, especially in Burma. But we will likely never know.”

Window to the world

“Many intellectuals and monks undertook cultural exchanges in the temple, when they sheltered here during the wars,” says Ieong. “Afterwards, they left Macao and travelled the world – disseminating the knowledge they’d gained through experiences there.”

Those experiences, of course, included witnessing Master Guanben’s work to raise women’s social status through education.

Ever since the Kong Tac Lam archives made it to the UNESCO Memory of World Register for Asia-Pacific, the Macau Documentation and Information Society has been organising events to promote the temple as one of Macao’s hidden gems. Ieong sees the archives as providing foundations to Macao’s identity. “As Macao residents, we should understand our various cultures and find confidence and a sense of belonging in our cultures,” she says.

Today, Ieong continues her in-depth research into Master Guanben’s life, ideas, and legacy – all of which inspire her, she says. “Master Guanben was a selfless person. He was eager to contribute to society while also passionately preaching.”