A koala named GranPa, who happens to be a retired astronaut, and young Zoe the dingo enjoy chatting about science on their farm in the vast Australian Outback. One day, they notice the sunlight is fading well before dusk. To find out what’s blocking the sun’s rays, the pair journey into outer space – meeting GranPa’s old alien nemesis along the way.

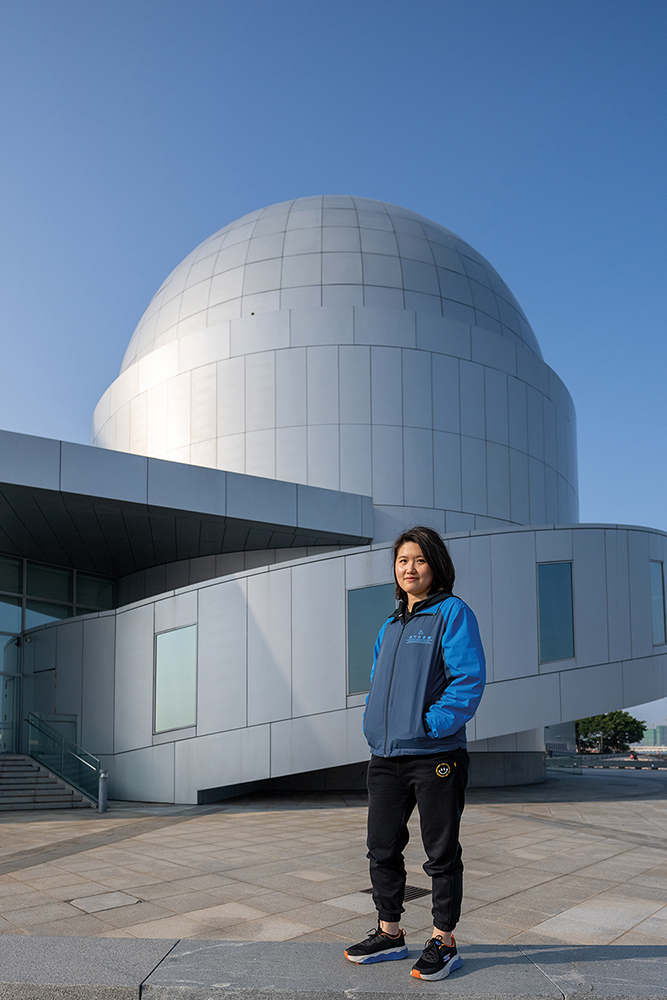

GranPa and Zoe are cartoon characters, in case that wasn’t obvious. They star in one of the Macao Science Center (MSC) planetarium’s five science-themed movie offerings. It is most popular, according to MSC planetarium officer Luisa Mak, a Macao-born scientist who majored in physics at a university in the United Kingdom.

These are ‘full-dome’ movies, displayed across the 127-seater planetarium’s 15-metre-diameter replica of the night sky. Audiences are physically immersed in the story as the dome’s screen – reaching up to the ceiling and taking up a quarter of the back wall – gives an almost 360-degree view. These movie screenings at the planetarium began when the Macao Science Center opened in December 2009.

All MSC’s full-dome movies are designed to appeal to children and spark an interest in science. They’re animated and run for about 30 minutes. While the movies are played through the planetarium’s audio system in Cantonese, each seat is equipped with headphones and interactive controls that allow viewers to choose Mandarin, English or (for select movies) another language if they prefer.

Back in 2010, Macao’s planetarium was awarded the Guinness World Record for having the highest 3D resolution in the world: 8,000 x 8,000 pixels. During Sky Show displays, its 12 digital projectors use space agencies’ data – such as from the NASA Exoplanet Archive and Sloan Digital Sky Survey – to show any documented object in the universe. The local planetarium also shows images taken by the James Webb Space Telescope, the new and largest optical space telescope that was launched on 25 December 2021.

While digital projectors haven’t yet achieved the brightness and clarity of older-style planetariums’ analogue projectors, those ‘star-ball’ systems can only show objects that are visible from Earth – and not in 3D.

Macao’s world record for 3D resolution has since been beaten. France’s La Coupole Planetarium, for example, boasts 10,000 x 10,000 pixels. But 38-year-old Mak says her planetarium’s full-dome movies draw more visitors than its Sky Shows, anyway. Their compelling storylines and offbeat characters are the venue’s biggest drawcard.

In award-winning Polaris 3D, for example, a penguin from the South Pole named James meets Vladimir the polar bear – hailing from the North Pole – on a slab of ice in the Arctic. The two creatures become fast friends as they discuss their respective regions at the opposite ends of the Earth. Polaris addresses concepts like the Earth’s tilted axis, different types of planets, and why there’s ice in the solar system.

The more traditional Sky Shows – narrated tours of time and space – do remain an important part of the planetarium’s offering. These journeys introduce audiences to various objects within and beyond our solar system, including planets, stars, constellations and galaxies.

“We can show models of the solar system and star constellations; we can fly from Earth to the outer galaxies using virtual reality-like technology,” says Mak. “Our system also predicts what might happen in the solar system, or the universe, in the future. Things like solar eclipses. The planetarium can simulate these events for viewers.”

The next generation of scientists

In 2019, nearly 80,000 people stopped by the planetarium’s NAPE waterfront premises – 11 percent of MSC’s total visitors. Even during the Covid years, the planetarium drew around 50,000 people annually.

Most visitors are school students, usually accompanied by parents. Weekends are the busiest time, attracting people all the way from Hong Kong and the mainland.

“Interest in science among locals is certainly growing,” says Mak. “Our wish is that when they go to the university, they will choose science subjects.”

Afterall, these are subjects ever-present in our daily lives. There is science in everything, Mak notes.

“For example, our mobile phones and all the technologies we use every day are part of science.”

In a bid to get more Macao youngsters signing up for science degrees, MSC teams up with local primary and secondary schools. It launched its Science Popularisation and Education Programme for Students scheme in November 2022, welcoming 99 separate classes – from various schools in Macao – across the inaugural two-month-long programme. Each visit aligned with students’ school syllabus and included a visit to the planetarium, which Mak says is always a highlight.

“Instead of just reading books, these students can learn science in a more fun way in order to make them more interested in it,” she says.

For the star-struck general public, the planetarium hosts a walk-in Starry Night programme. This is a lecture series held inside the planetarium, and participants sometimes get a chance to observe the real night sky using one or two giant telescopes set up outside by planetarium staff – CFF Telescopes Classic Cassegrain 350mm and Sky-Watcher StarGate 20’’ SynScan Dobsonian.

Over the past three years, Covid-19 restrictions made the Starry Night sessions difficult. Lectures would often be cancelled, or shifted online. Macao’s open borders mean the events are, again, in person. In July, for example, Hong Kong-based Lydia Lung, from the astronomical NGO AstroLink, is scheduled to present a fascinating history of space suits.

Last year, the planetarium participated in “Science Dreams in Light and Shadow”. This was a national tour of ‘scientist spirit films’ celebrating Chinese pioneers in science, as organised by the Chinese Association of Natural Science Museums.

The six movies introduced viewers to the likes of female astronomer Ye Shuhua, born in 1927, who is best-known for her groundbreaking work in the 1960s measuring Universal Time (which reflects the Earth’s rotation).

“Macao people should be proud of these Chinese scientists who overcame their difficulties and patiently experimented over and over again until they made their discoveries,” Mak stresses. “We want to share this spirit with our youngsters.”

The films are still available to be viewed at the planetarium, though only with a special group booking.

A user review

Five-year-old Jonas Wong, from Hong Kong, recently visited Macao’s planetarium with his parents. He gives a rave review of the place, saying he enjoyed the way the solar system was depicted using 3D effects.

“I learned lots about the universe and sun,” he enthused.

The kindergartener saw the full-dome movie GranPa & Zoe; he readily affirmed that the Australian characters were “so cute”. What will warm Mak’s heart most, however, is Wong’s assertion that he learned something new about science.

“We want kids to leave the planetarium realising that science is not boring; it is interesting, and we can learn it through entertainment,” she says.

Five facts about planetariums

1 – The world’s first planetarium (pictured) was a clockwork model of the solar system, known as an orrery. It was built between 1774-1781 by Eise Jeltes Eisinga, an amateur astronomer from the present-day Netherlands. Eisinga constructed the orrery in his own home, now a museum called the Royal Eise Eisinga Planetarium.

2 – This year marks the 100th anniversary of the world’s first planetarium projector – first lit up in Germany in August 1923.

3 – Planetarium domes tend to be in the shape of a perfect half-sphere.

4 – Contrary to what many think, most planetariums still only offer 2D displays of the night sky. Macao’s offers both 2D and 3D displays.

5 – The disposable 3D glasses used in ordinary cinemas are not effective in planetariums offering 3D night sky displays and shows. Rather, planetariums use special electronic 3D glasses that are able to block information meant for one eye from the other.