When Leong Chong Leng immigrated to Macao in 1978, he says most parents had one rule for their children: they could not take up martial arts, a practice associated with fights and crime.

The SAR has come a long way since then.

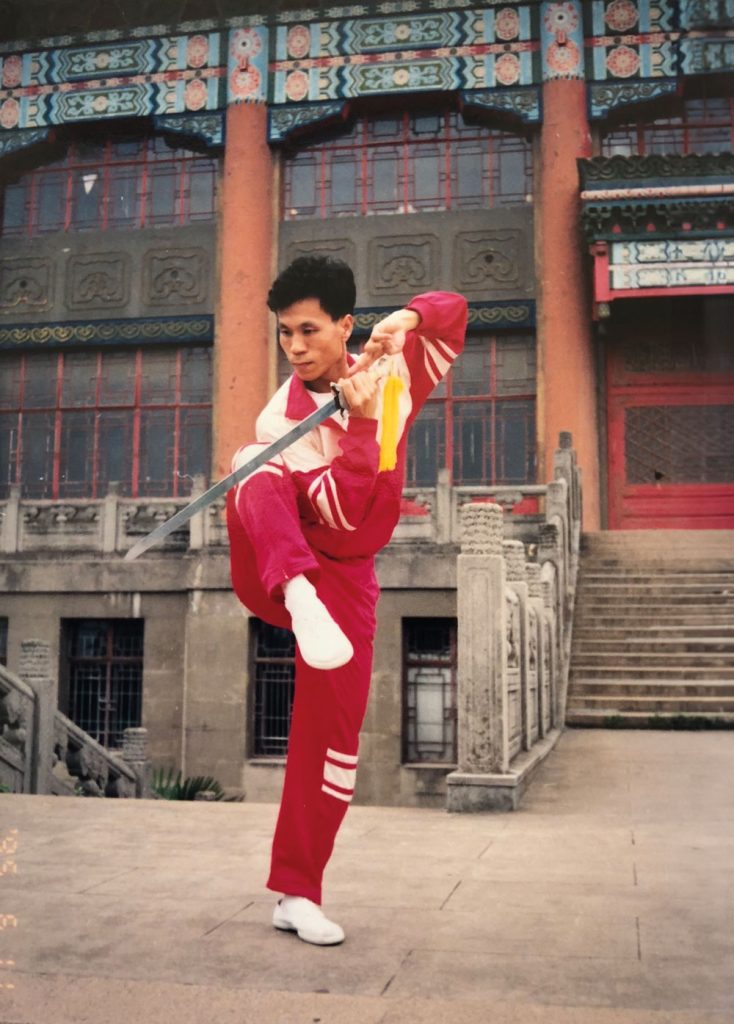

Martial arts have boomed in Macao. Whether it is tai chi or wing chun, a branch of kung fu preserved as an intangible cultural heritage, the different disciplines have courted many thousands of practitioners. Some, like Leong, a martial arts champion in the 1980s and 1990s, have even won global competitions as representatives of Macao.

It is in Leong’s sport of wushu where Macao has truly punched above its weight.

At the 19th Asian Games in Hangzhou last year, Macao won four medals in wushu, including one gold, as star athlete and Silver Lotus recipient Li Yi was crowned champion in women’s changquan, one of three wushu disciplines. Just weeks later, she became world champion in qiangshu at the 2023 World Wushu Championships in Dallas, Texas.

Her win in Dallas was one of 11 medals won by Macao – five gold, two silver and four bronze – placing the city in third place.

To compete with global powerhouses, Macao and its athletes have had to focus on sustainable progress. The city’s success in the sport is the result of discipline, dedication and steady investment. Not least the establishment of the Wushu General Association of Macau (WGAM).

A brief history of wushu

Wushu, meaning ‘martial technique,’ is a display- and contact-based competitive discipline based on several Chinese fighting techniques. As a sport, though, it is relatively young.

The development of organisations such as the Shanghai Jing Wu Physical Association and the inaugural Chinese National Wushu Games in Shanghai in the early 20th century helped to codify and modernise martial arts traditions. Later, the founding of the International Wushu Federation (IWUF) in 1990 created the first global governing body, which catalysed its growth outside the country. The sport has since expanded to 155 national federations under the IWUF, and it has twice been shortlisted for inclusion in the Olympic Games.

As a tradition, though, wushu has existed perhaps for millennia. The IWUF believes its history goes as far back as the Bronze Age (3000 to 1200 BC).

Even so, the martial arts did not arrive in Macao until the late Qing dynasty (circa 1644-1911). Later, when the imperial Japanese army invaded China, many Chinese residents fled to Macao, bringing wushu with them. They established schools, and soon the martial art took off.

How Macao became a hotbed for wushu talent

In 1982, Ho Yin, the father of Macao’s first chief executive, Edmund Ho, set out to establish a wushu association to elevate the martial arts. Ho passed away in 1983, putting the project on hold, but his son would bring his vision to life. On 28 June 1988, the WGAM was founded.

“The martial arts world has always been a patriotic community,” explains Leong, who today coaches wushu and is a vice president of the WGAM. By uniting athletes in an official organisation, “[wushu practitioners] would be able to support the nation in times of need.”

Despite its martial roots, wushu has largely grown as an artform.

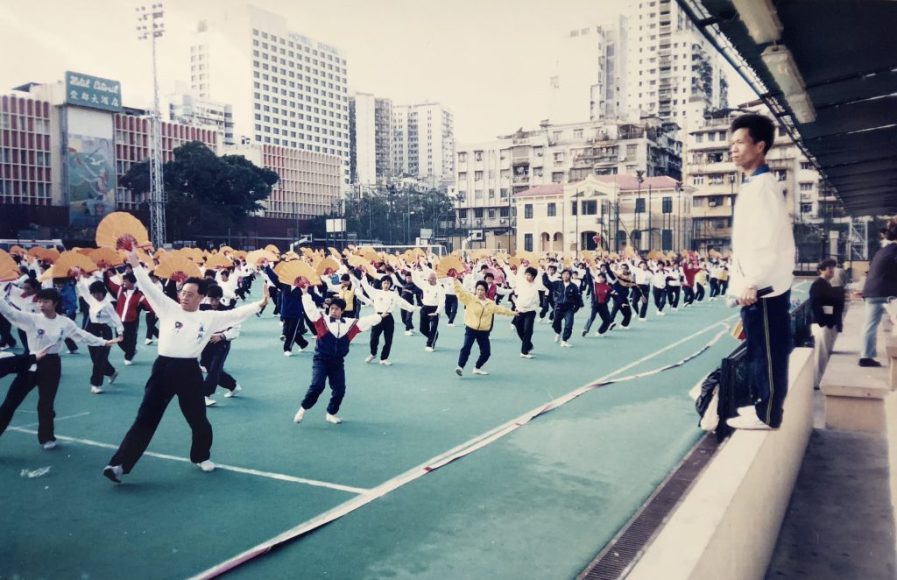

For years, the different practitioners and their institutions would gather for the annual National Day Celebration on 1 October. They would perform and compete at Cinema Alegria, or the Campo dos Operários (a sports ground where the Grand Lisboa now stands), or the Tap Seac Football Ground, which was replaced with Tap Seac Square in 2007.

Wushu masters in Macao such as Chiu Chuk Kai, known for the ‘praying mantis’ style; Man Chong Kong, a proponent of Choy Li Fut, one of the city’s most popular forms of wushu; and Lei Man Iam, a teacher of Chen-style tai chi, have illuminated its diversity, fluidity and complexity.

These events and teachers helped to establish wushu as a sport of purity, focus and discipline.

When the WGAM was founded, the city’s leading athletes and emerging talents had more formal competitions and pathways to develop. Today, with 118 affiliated organisations and close to 10,000 members, the WGAM plays an indispensable role in competitive wushu in Macao.

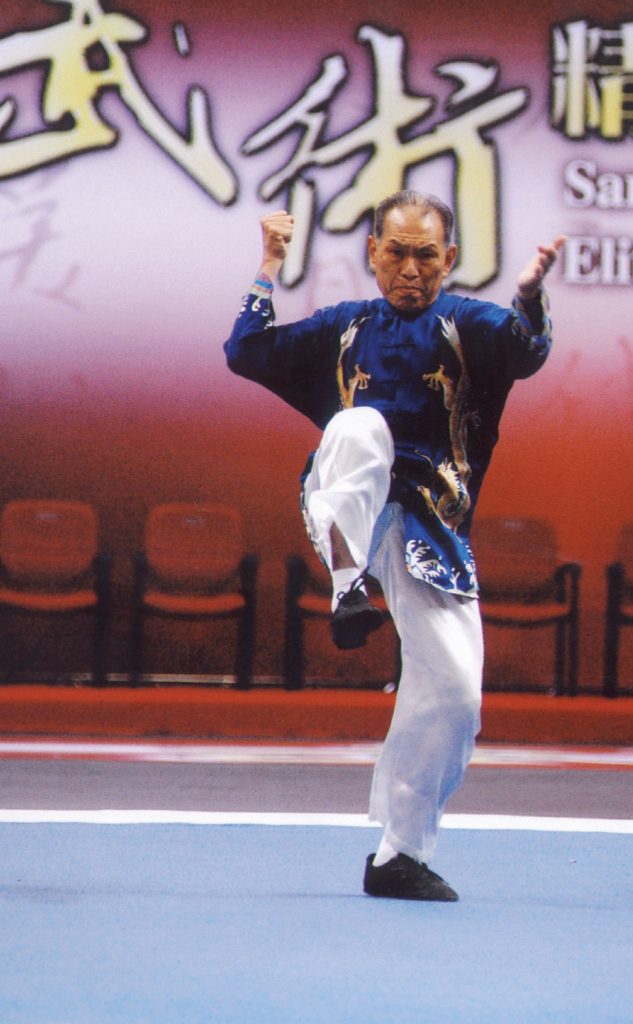

According to Leong, the association holds a number of regular competitions each year, including the Macau Wushu Championship and the Macau Junior Wushu Championship, both essential recruiting events for the junior and senior national teams. Leaders such as Leong do not solely focus on gold medal winners, either. The competitions, he explains, often bring candidates who display potential for excellence to the WGAM’s attention, even if they did not win gold.

Thanks to the WGAM, Macao has so far supported three Asian Games winners: Li Yi, as well as Jia Rui and Huang Junhua, who won gold in men’s wushu in 2010 and 2018, respectively.

Taking the next step

Success in any athletic endeavour requires commitment. Wushu is no different. “The hours are very long,” says Leong. Elite athletes train from 6 pm to 9 pm every night but Sunday all year long. “If you don’t train consistently, the physical gains from your earlier training will disappear,” he explains.

But Macao athletes have bought into the intense training programmes, and the WGAM in turn has provided new opportunities that have helped them reach new heights.

The teams regularly train with some of the best wushu athletes in the mainland. “Sometimes we train in Beijing, Fujian and the different provinces,” Leong says. “We do short-term training in whichever place has a higher level of wushu [mastery], especially during the summer.”

The Macao government has been essential for these off-site training trips, covering expenses for up to 30 athletes each time. The government has also given the association’s junior and senior martial artists access to its Athlete Training and Development Centre, where they can train using top class facilities and equipment. The Sports Bureau collaborated with the WGAM to establish the Macau Wushu Youth Academy as well. This academy launched in 2007 and has proven itself vital to training Macao’s next generation of wushu talent.

The investments have paid off beyond Macao’s recent run of medals on the global stage.

Wushu’s image has evolved since Leong arrived. The WGAM has stressed wude (武德), the martial arts code of conduct, to frame its inherent sense of camaraderie and respect for others. By promoting the benefits of wushu, tai chi and other martial arts on the body and the mind, the WGAM has helped Macao residents improve their well-being. Martial arts are not solely the domain of elite athletes; rather, they can be the foundation for a healthy and active lifestyle.

Wushu may be young as a competitive sport, but it is growing rapidly. A wushu tournament took place alongside the 2008 Olympics in Beijing as an unofficial sport – the first time the International Olympic Committee allowed such an event, owing to its cultural significance. In 2026, it will debut at the Youth Olympic Games held in Dakar, Senegal. The Olympic Committee has promised to deliberate on the sport’s future in the Olympic Games following that event.

It is clear that wushu is on the rise. Thanks to the government’s continued investment in the sport, Macao athletes could soon add more impressive international titles to their growing mantle of medals, though they cannot yet compete in the Olympics due to Macao’s status as a non-member of the International Olympic Committee.