TEXT Karen Araño Tagulao, Institute of Science and Environment, University of St. Joseph

Mangroves serve as roots of the sea, they protect our shorelines and are a nursery ground for our biodiversity.

Take a trip along the bicycle track areas on the Taipa waterfront on Avenida dos Jogos da Ásia Oriental or the Lotus Cycling Track along Avenida Marginal Flor de Lotus in Cotai, and you’re sure to spot the clusters of trees and other plants along the coastline. You may not know, however, that these are mangrove forests, one of the most ecologically valuable ecosystems in the world. Join us for an exploration of this local treasure, and uncover a world full of mystery and dynamics, the world of mangroves!

The word mangrove originates from the Portuguese word mangue or Spanish word mangle meaning “tree” and the English word “grove” for a group of trees. Known in Chinese as 紅樹林 (red forest), mangroves are a special group of trees, shrubs, and other plants that thrive in coastal saline and brackish waters, particularly along the fringes of estuaries and lagoons. This means that the mangroves are able to tolerate salty water brought about by fluctuations in tides and river flow, ranging from being partially submerged during high tide to exposed at low tide. Other plants would struggle to survive in such a harsh and changing environment, but mangroves have developed many physiological (functioning) and morphological (physical) adaptations that make them quite unique.

These physical adaptations tend to be the most distinguishing features for ordinary people first encountering mangroves.

Each forest is a maze of roots and branches wriggling out of very soft, and sometimes smelly, mud. To survive in the changing water conditions along the coast, mangroves like those in Macao have developed “breathing roots” called pneumatophores, which look like fingers protruding above the soil surface. Other mangroves have prop or stilt‐like roots which not only allow for “breathing” but also provide support from the impacts of tides and waves.

We don’t often think of plants as needing to breathe, but plant roots need oxygen for respiration to stay healthy. This

is difficult in a mangrove forest where the soft, water‐saturated soil limits gas exchange, making the soil oxygen poor. Pneumatophores allow mangroves to get the oxygen they need, and the widely spread horizontal roots they grow, help anchor the plants in unstable mud.

That mud may not smell very nice – many liken it to the smell of rotten eggs – but it’s natural and temporary, not at all a cause of worry. The smell is from sulphur dioxide produced by the anaerobic bacteria that decompose the dead plants and animals in the anoxic, or oxygen poor, soil.

Mangroves have also developed strategies to deal with the salt in their environment. For most plants, even the relatively lower salinity of brackish water would reduce growth at best, and kill at worst. Not mangrove species! They can excrete salts from their leaves or exclude salt from entering their roots when taking in water – some do both.

While mangroves would happily grow in freshwater, their ability to tolerate salt gives them a competitive advantage over other types of plants.

Another very interesting adaptation of some mangroves species is the ability of seeds to germinate while still with the parent tree, called vivipary. These candle or pen‐shaped seeds can float and attach to sediments, taking root where water is shallow enough. This process helps mangroves propagate and survive in the very unstable intertidal environment.

Global forest, local flora

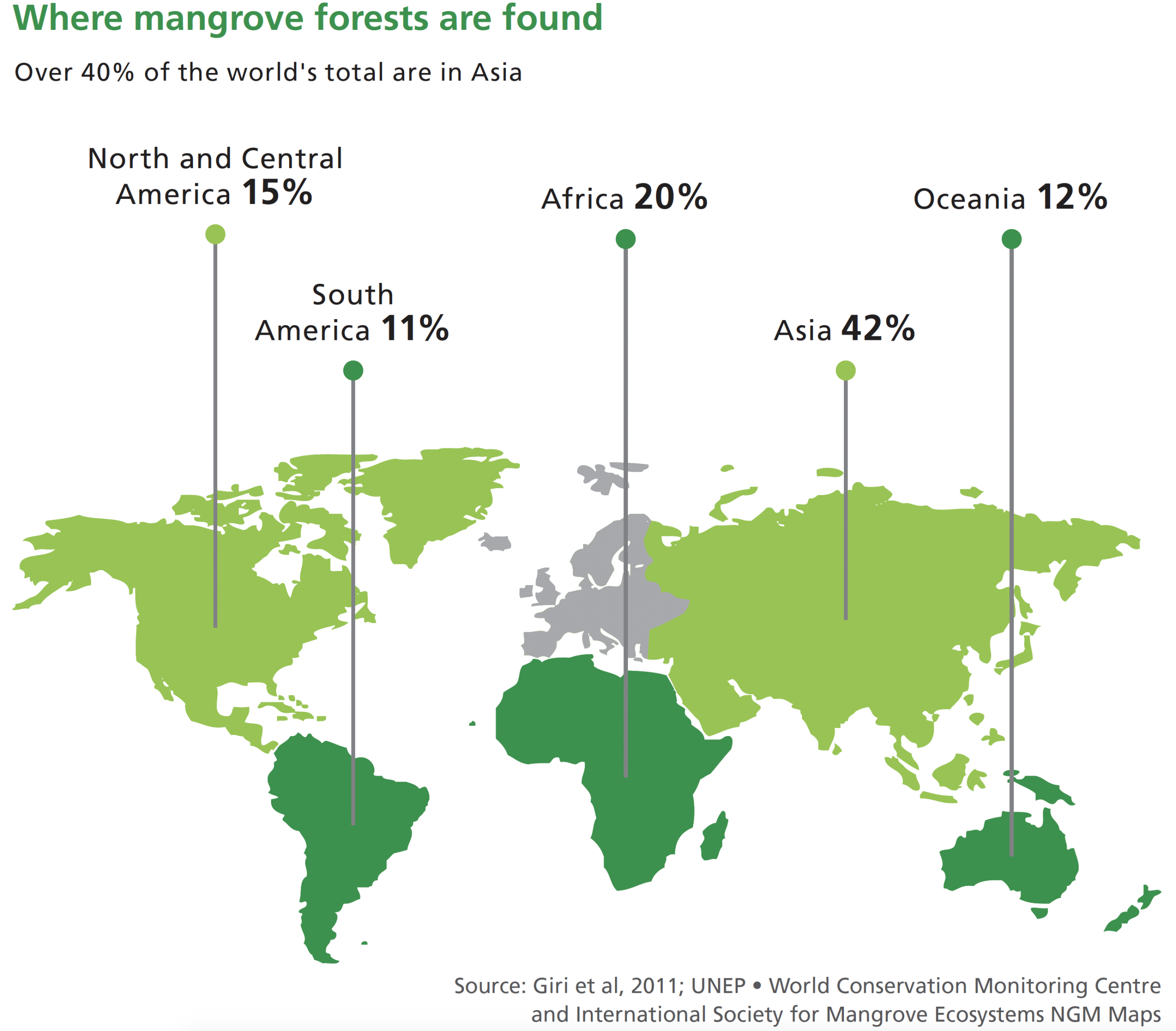

These remarkable adaptations allow mangrove forests to grow in sheltered tropical and subtropical coastal areas in 123 countries and territories around the world. Did you know that most mangroves – 42 per cent – are found in Asia? The rest are in Africa (20 per cent), North and Central America (15 per cent), South America (11 per cent), and Oceania (12 per cent).

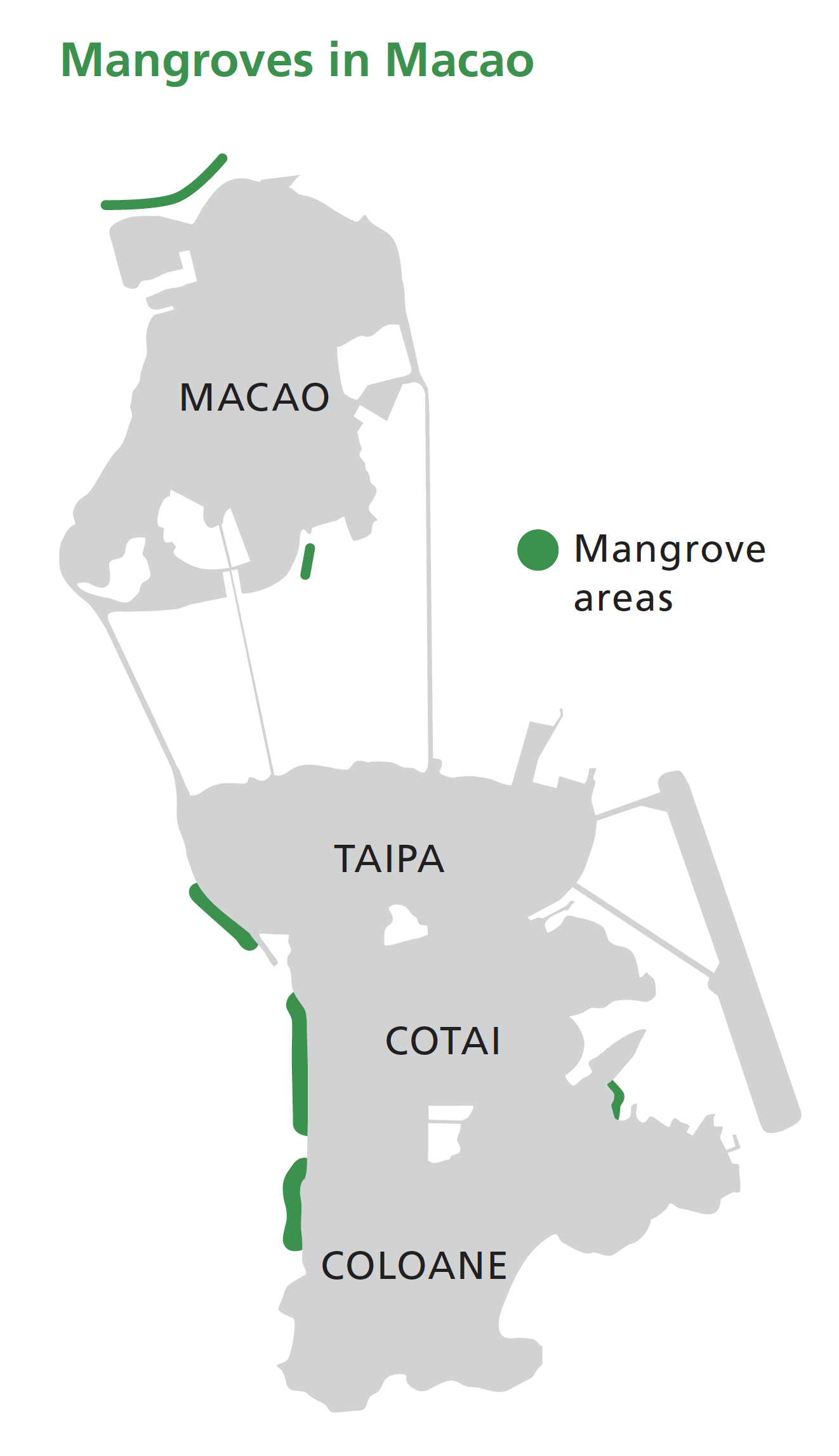

Macao, despite its small size and highly urbanised environment, is home to a healthy stand of mangrove forest along approximately four kilometres of the Taipa‐Coloane coastline. The majority of these mangroves grow within the 40‐hectare Ecological Zone II in Cotai managed by the Environmental Protection Bureau. Some patches can also be found in a small protected area in the eastern side of Coloane as well as Macao Peninsula. It is quite amazing to see an ecosystem like mangroves growing alongside the glitz and glamour of a city like Macao.

Mangroves in Macao

But why is the whole 50‐kilometre coastline of Macao not covered with mangroves? It is because not all coastal areas are a good fit for these forests. Mangroves can only grow in areas protected from high‐energy waves, but they need some tidal activity to bring in nutrients, aerate the soil, and stabilise salt levels in the sediment. That’s why we don’t see mangroves on the beaches of Hac Sa or Sai Van or along the rocky shores in Coloane.

Now that we know what mangroves are and where we can find them, which species grow in Macao? Mangrove plants are taxonomically diverse, meaning they are not necessarily closely related or belong to the same family, but share similar

functions and adaptations. There are more than 70 mangrove species worldwide – each suited to different biogeographical regions, estuary locations, and intertidal positions – and six species right here in Macao.

The smallest of these is the mangrove fern, Acrostichum aureum, which is very sparse and mostly found closer to the land than the sea, together with other mangrove associates. One of the most dominant landward species is Acanthus ilicifolius, a shrub commonly referred to as sea holly because of its spiny stems and serrated leaves. In springtime, these shrubs blossom into a beautiful field of purple and white flowers, a rare natural delight in a city like Macao.

The smallest of these is the mangrove fern, Acrostichum aureum, which is very sparse and mostly found closer to the land than the sea, together with other mangrove associates. One of the most dominant landward species is Acanthus ilicifolius, a shrub commonly referred to as sea holly because of its spiny stems and serrated leaves. In springtime, these shrubs blossom into a beautiful field of purple and white flowers, a rare natural delight in a city like Macao.

So why are mangroves known as “red forests” in Chinese? Some say that the name originates from the red dye once made from the aptly‐named red mangrove, Rhizophora. Although Rhizophora is not present in Macao, the city is home to Aegiceras corniculatum, commonly known as the river mangrove, which has a reddish petiole or leafstalk. There are also grey mangroves, exemplified by Avicennia marina, a very common species that can be seen from the mid‐ to seaward mangrove margins in Macao.

Kandelia obovata and Sonneratia apetala are both easily propagated, making them popular for mangrove restoration projects.

Have you ever seen a plant with long candle or pen‐ ‐like structures hanging fromits branches? This is K. obovata, known locally as “water pen,” and its viviparous seeds.

While the K.obovata and the other species are native to Macao, the mangrove apple, S. apetala, is another story. Originally from Bangladesh, it came to Macao by way of mainland China. Its resiliency and fast growth rate make the mangrove apple well‐suited to restoration, but there are concerns because it is also invasive and might outcompete native species in the area.

Beneficial ecosystem

So what if there are mangroves here in Macao? Why should we care? Well, for a long time, people didn’t care. The soft mud and sulphurous smell gave mangroves a bad reputation; many labelled them “wastelands” of little or no value. But over the years, researchers have shown that mangroves provide a wide range of benefits to the ecosystem and to humans.

The mangroves of Macao contribute significantly to local biodiversity. How can that be with only six plant species? For one, mangroves provide homes and shelter to many plants and animals, both terrestrial and aquatic. Local birds live there, and many migratory birds, including the endangered black‐faced spoonbill, winter in the mangroves. They also serve as breeding and nursery grounds for various aquatic animals including fish, crustaceans, and molluscs.

But mangroves do more for humans than provide a great bird‐watching experience. They also help make Macao a cleaner, safer environment. Because of its geographic location and hydrographic processes in the area, pollution of the coastal waters can be an issue in Macao. Mangroves, sometimes called “natural wastewater treatment facilities” due to their ability to filter pollutants such as heavy metals, help improve the quality of coastal waters. They trap sediments, leaving water clearer, and uptake nutrients. Their ability to trap pollutants helps protect adjacent areas, lessening the damage to marine life.

Mangroves, together with seagrasses and salt marshes, are also receiving more attention worldwide because of their role

in climate change mitigation and adaptation. In a coastal city like Macao, vulnerable to impacts of storm surges, mangroves can help physically protect the coastline by acting as a “green wall,” buffering the impact of strong waves. This helps prevent and reduce coastal erosion while also providing a measure of protection to people and property in coastal areas. We need only look back on the devastation wrought by flood waters during Super Typhoon Hato last year to see the value of investing in a natural barrier against storm surge.

Moreover, because of their unique root system and soil conditions, mangroves far outpace terrestrial forests in their ability to capture and store large quantities of carbon. Much of this carbon is stored belowground in the soil and dead roots, minimizing their carbon release into the atmosphere. They also filter air pollution, which can be an issue in Macao, and supply oxygen for the city.

Mangroves, sometimes called “natural wastewater treatment facilities” due to their ability to filter pollutants, help improve the quality of coastal waters.

Mil Homens

Habitat under threat

Despite their proven value, mangroves have long been marginalised and face constant threat worldwide. More than 35 per cent are already gone, and an estimated 1–3 per cent of global area is lost each year. This is primarily attributed to human activities such as the clearing of mangrove forests for aquaculture or the impact of rapid development in coastal areas. But there is cause for hope.

Researchers have estimated that rates of decline in some areas in the world have recently lessened because of improved conservation measures, and many communities are investing in restoration. What about Macao and its mangroves? For those who lived here before the rapid modernisation, you may remember how Taipa looked when mangroves occupied the now freshwater wetland in front of the Old Taipa Houses‐Museum.

During the reclamation, the mangrove plants were transplanted from that area to their current home, Ecological Zone II in Cotai. Our forests are generally in good health, but still vulnerable to pressures from the rapid and massive development adjacent to where they live.

How can we help? We can prevent further destruction of mangrove forests by not polluting their habitat and restoring mangrove forests by planting nursery raised seedlings.

Some parts of the coastlines in Taipa and Coloane are being planted by the government, but there are still other potential sites for restoration around Macao, Cotai, and Coloane. There is hope, that through scientific research, public education and awareness, as well as cooperation of both the government and the local community, Macao’s mangroves will continue to thrive and expand.

The next time you visit Macao’s coastline, remember these remarkable mangroves and how much they give back to us – and consider what you can do to help protect these natural treasures for years to come.