TEXT Leonor Sá Machado

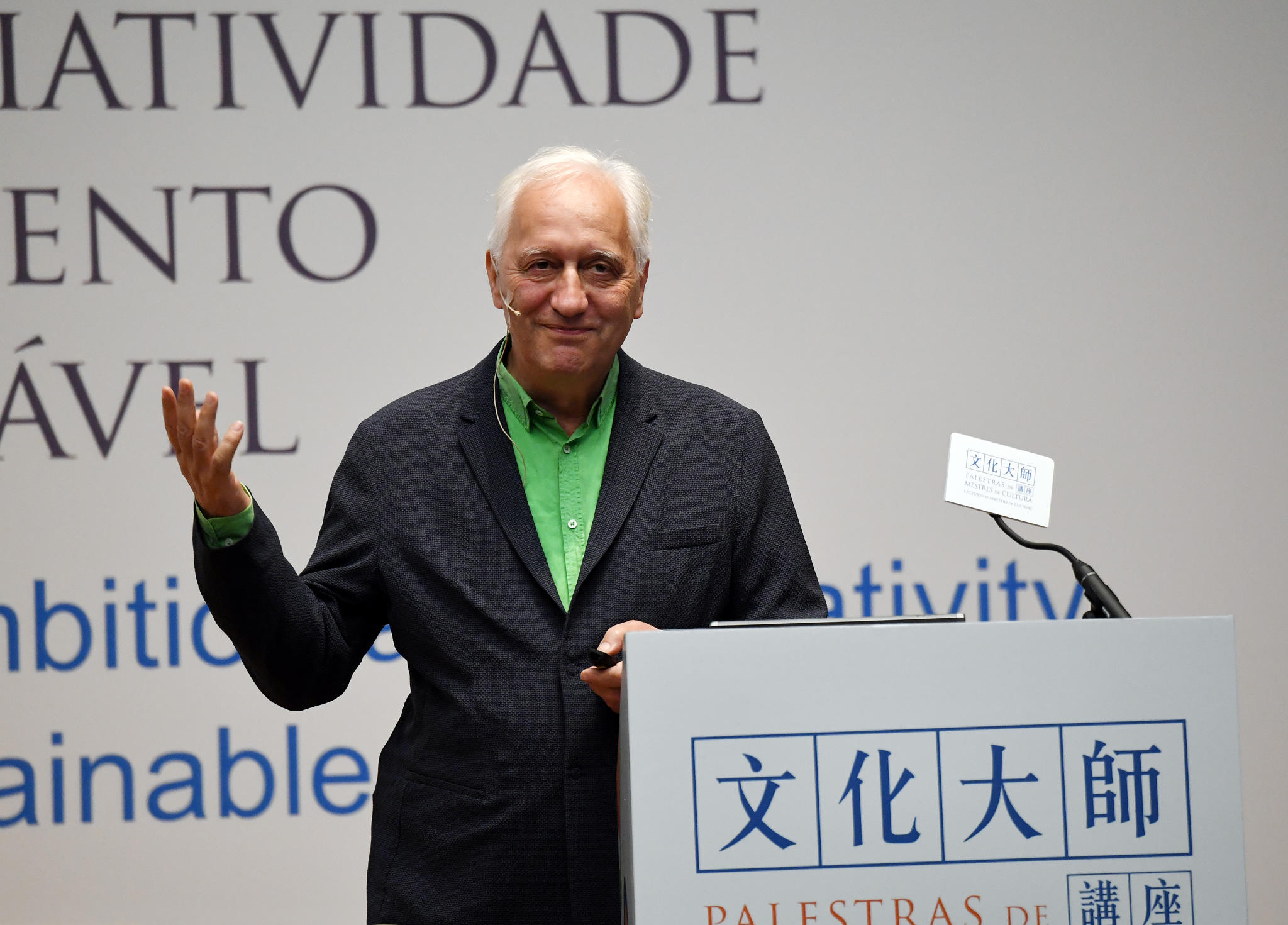

Urban planner Charles Landry contemplates on the path to a greater Macao, which he believes involves more investment from casino operators, a closer relationship between local residents and government authorities, and improved urban planning

Urban development specialist Charles Landry visited Macao last month. On this visit to the territory, his third, Landry spent much of this time observing the city on foot, strolling through local districts including Old Taipa Village and Portas do Cerco.

Landry is founder of Comedia, a think tank focussing on urban change and development. He is also renowned for coining the term the creative city. In very simplistic terms, he explains that in order to effectively respond to modern urban change, creativity is required at every level of adaptation. Therefore, a culture of creativity must be nurtured in order to provide the most fruitful environment for harnessing all resources and potential to yield the most optimal outcome. For Landry, creativity is context‑driven throughout time. For example, “In the 19th century, we had to deal with public health, and solving those problems was a creative act,“ he explains in an interview with Macao Magazine.

According to Landry’s city categorisation system—City 1.0, City 2.0, and City 3.0—he deems Macao a “spectacularised city 2.0”, where, among other traits, architecture and design are mainly conceived for spectacular effect. And like other 2.0 cities, he sees Macao as needing to improve connectivity in general and to further a community‑driven mind‑set.

At a lecture he gave at Macao Science Centre entitled “Macao: A Culture of Ambition and Creativity as Catalysts for a Sustainable City,” Landry started by asking the audience to first envision the kind of city they want to live in. In order to successfully execute any plan, before all else, “It’s necessary to choose the model you want to follow,” he clarified. While some would like to live in a shiny metropolis, others prefer smaller, calmer cities or one that is more tech‑friendly and environmentally‑conscious. Urban planning is about defining how to achieve a specific goal; it does not define what that goal ought to be.

Regardless of personal preference, everyone can agree on one thing: Macao’s ambition. “Macao has been ambitious creating casinos, universities and metros, but is this what you want?” Landry wonders. Using contrasting cities Dubai and Buenos Aires as examples, the urban planner highlights the need to have a clear vision. In his experience, people want human scale architecture, a sense of place, affordable housing, and to feel that their city is “a city for all” growing with everybody’s help and connectivity. “What makes a great city, in my opinion, is an interweaving [of disciplines and areas of knowledge].”

How going corporate would help Macao thrive

Landry believes that for a city to grow, there has to be greater economic investment as well as increased development with regards to societal well‑being, although the two cannot both grow concurrently at the same rate.

The urban specialist urges casino operators to implement better corporate social responsibility (CSR) plans and put their enormous gaming revenues, which far exceed that of Las Vegas, to good use by supporting Macao’s social and cultural development. He also suggests employing more local companies and start‑ups in their supply chains. “There’s a vast set of skills involving what the casino operators do which has to do with creative economy.” When asked how one might inspire such big companies to action, Landry explains that external pressure is often effective, starting with citizen-led discourse.

Graphic designer and founder of Macao Creations, Wilson Lam, agrees that big, established companies ought to mentor and support smaller ones for the greater good of the city’s future. “Macao has its unique gambling hub going on and that’s all good and well but we should be using it as a stepping stone for the next city version.” Macao Creations is a branding and product design, sales, and manufacturing company based in the region. In addition to their own products, the company often showcases the work of local artists.

Building a city, not just a destination

Creating a destination, Landry argues, is different from creating a city. Destinations are a short‑term stay concept, whereas a city is meant to be sustainably liveable. He cautions against a collective apathy combined with a lack of creative vision, which would cripple progressive urban development. Within the urban planning community, there is growing concern that the ratio of spectators to makers is too high, that action is making way more and more for passivity. Landry fears that “people don’t acknowledge the resources Macao has”, but is encouraged by the region’s ability to transform when the proper resources are utilised, pointing to the St. Lazarus neighbourhood, which has been attracting more visitors following its revival.

What if a city’s population could actively participate in its evolution, bringing imagination to life and contributing to a safer, cleaner, and more liveable environment? This might sound utopian, but it is in fact a reality for many cities, Macao included.

BABEL, a local non‑profit, is doing precisely this. According to its website, the cultural organisation’s mission is “to generate learning opportunities in the fields of contemporary art, architecture, and environment. BABEL is conceived as a museum without walls and aims to work in between cultures and across disciplines.” By creating activities and live events where interaction is key, BABEL draw upon the public space as their stage, transforming spectators into actors.

Art curator Margarida Saraiva and architect Tiago Quadros founded BABEL in 2013. “We created the association because we felt there was a set of issues related to contemporary art, architecture, and the environment which needed to be discussed under different formats,” Quadros explains. He also underlines the need to curate different audiences, advocating for a strong education component in the form of workshops and exchange programmes with foreign schools.

Macau Architecture Promenade (MAP), one of their recent projects, debúted in 2015. The idea behind the endeavour is to foster people’s interest in contemporary art and architecture by making use of public spaces: gardens, conference venues, libraries and even walls, streets, and stairways. BABEL organised 30 international and local artists into more than 20 activities held throughout October, the international month of architecture. “The idea of MAP is to bring art into the public space,” says Quadros. However, he expresses frustration at the difficulty of putting on some of the activities due to bureaucracy and a “generalised inhibition (within local society) regarding the use of public space.” To eradicate this inhibition, he believes it is important to “break habits” and open people’s eyes to the endless possibilities.

Integrated oases add a cohesive sense of urban belonging

Landry advocates that a city like Macao should establish leisure and entertainment spaces for its residents, what he calls little “oases”. The idea, he explains, is to design different areas where people go to enjoy themselves and relax in contrast with other parts of the urban cityscape which are driven by commercialism and tourism. “Isn’t city making about a hundred small things rather than one big icon?” Landry questions.

The specialist points to the square surrounding St. Francis Xavier Church in Coloane Village which has green areas, a fountain, and some benches. “There should be ten times more places like these because a city like Macao needs zones of encounter.” Quadros concurs, adding that these public spaces should be without barriers. “Taipa Park, for example, is a public complex with several infrastructures, but it is surrounded by a huge steel railing which gives the idea of enclosure.”

According to local architect Carlos Marreiros, the existence of large public squares is one of the most profound identity traits of the Chinese metropolis. In the case of Macao, the city needs only provide the space. “People will do the rest.” Thus far, the region’s typology has supported his thesis. Marreiros cites Senado Square as a good example, with commercial spaces occupying ground floor units and residential units above. This identity trait of the large public space, the architect argues, should harness Landry’s theory regarding urban connection. “Macao had this connection [between people and places] once, but not anymore. I agree we should recover this sense of relationship; one could accomplish this with the pedestrianisation of some streets, for example.” The same goes for the Cotai Strip area, according to Landry: “The difference between a street and a strip is huge and [Cotai Strip] could be pedestrian‑friendly.”

The key, Landry argues, is creating a balance between different environments and mindsets rather than having them coexist in separate vacuums. This is one of the fundamental differences between ‘The City 2.0’ and ‘The City 3.0’. In both models, technology and enterprise hubs may comprise, for example, a garden, a pool and an alfresco shopping centre. But city 2.0 is more tech‑driven, keeping innovation campuses away from the city centre, whereas 3.0 mixes them all together, providing a sense of closeness and belonging.

Giving the people what they want

According to Marreiros, “[Macao] residents are now more aware and critical than ever, and that is a good thing.” The Macanese architect believes the community should be directly involved in the city’s development. “Macao is a city that really depends on the government, and that is not something you change overnight.” However, he believes there is also a strong sense of change that has to come from within the community: “People have to take a critical stand for the sake of their city.” For people to do so, he explains, decision‑makers have to be open‑minded and interactive, showing residents that their demands are being heard. “Real estate demand is so high that urban planners don’t even have to worry about fitting activities into their infrastructures; the community does it for them.”

Architect Rui Leão agrees: the community truly matters, and to that end, there is, he underlines, a group of citizens starting to take a critical stand on behalf of their city’s health and beauty. “There has to be more openness for people’s opinions because they are the ones who live and experience the city.” Leão surveyed several residents currently living in some of Macao’s oldest neighbourhoods who expressed that they, too, are interested in seeing these places revitalised. “There is a willingness to do so.” The architect is President of the International Council of Portuguese Speaking Architects (CIALP), created in 2011.

His partner Carlota Bruni suggests a different approach to resuscitating the region: “Tourists follow the tourism agencies’ routes and directions, so they only get to see the Ruins, Senado, and the Fortress, because that is what they are told to see. Then why don’t those agencies start including other streets and avenues in their itineraries?” Doing so, Bruni adds, would give new life to dying neighbourhoods which might inspire property owners to think about reinvesting in their assets.

Leão is also in favour of renewing the city centre, which most architects and residents alike would agree is quite neglected. “It has a lot of potential, but people are just waiting for it to fall apart.” He also advocates that the Fund for the Cultural and Creative Industries should adopt a broader approach when considering project proposals. “The evaluation method should consider many other factors besides profit margin,” for a start. Leão strongly believes that decision‑makers should take the city’s overall development into account when examining potential projects. “The fund should approve things which help reshape the city.”

There is a consensus among the city’s architects that there is an ever‑growing sense of demand from the population and an undeniable will from residents to revitalise their neighbourhoods, such as city centre. They, like local residents, believe Macao has the potential to become a happier, more liveable and dynamic city, within its constraints. “So why not give people what they want?” Leão asks.

A future of possibilities

One of the government’s long‑term goals is to transform Macao into a “cultural capital”, which Landry believes is entirely feasible. To achieve this, he encourages a stronger sense of interdisciplinary cooperation not only between big companies and start‑ups, government, and local entrepreneurs, but also with the community. Landry stresses the need to be open to new ideas, to invest and to experiment, perhaps looking to other cities—such as Helsinki in Finland—for practical models.

Landry, Leão, and Bruni have suggested several different ways of innovating and bringing creativity into the city, many of them requiring no monetary or time investment to implement.

Lam, of Macao Creations, expresses concern at Macao’s lack of diversity when it comes to an experienced and educated populous, due to the city’s yet nascent university‑level education system. “We [artists] try to do our best, but it is difficult to innovate. Decision‑makers should do something in terms of funding to promote art and education and inspire locals through access to the best training in the world.”

Drawing from present inspiration for the future

Landry concluded his lecture by pointing to some already creative aspects within Macao, praising Albergue SCM’s cultural hub as a good example of balancing the old and the new as well as Sir Robert Ho Tung’s restoration project for its contemporary outdoor design.

Although Bruni agrees that people appreciate these kinds of spots, she prefers a wider and more connected sense of urbanism rather than simply “planting a park with a sports pavilion, a pool, a garden, a running track, and a library in a single space.”

Landry’s cities

Landry’s City 1.0 is characterised by strong development of the industrial sector with an emphasis on factories and mechanisation. Its movement peaked between the 1960s and 1980s when wide‑spread road infrastructure boomed as personal vehicles became popular. “The management and organisational style is hierarchical and top down…vertical with strong departments, and there is little if any partnership.” Technology and creativity are set aside to prioritise mass production and infrastructure construction.

The 90s mark the development of City 2.0. These cities are more tech‑driven, valuing technology and science development hubs. Work environments become more open to new ideas, and the concept of collaboration within the work‑place starts to spread. Consumption is the main trend, with architecture and design playing a leading role in urban life. The population of 2.0 cities are more connected and assertive. “There is also a move to reflect human need and human scale. How people interact rises up the agenda…The city is less car‑dominated, walkability and pedestrian‑friendly street design with buildings close to the street become a priority, as do tree‑lined streets or boulevards, or street parking and hidden parking lots.”

The City 3.0 is mainly characterised by a strong interweaving between citizens, places, environments, attitudes and decisions. In 2.0 cities, tech hubs are built far from the city centre: City 3.0 puts it all together, creating different spaces with different mind‑sets in close proximity. Roads and streets are no longer solely for cars but also for people: large parks and promenades invite the public to enjoy the outdoors. The 3.0 city “can be called ‘soft urbanism’ as it takes into account the full sensory experience of the city. In making the city, it considers the emotional impact of how people experience the built fabric and thus is strongly concerned with the public realm, human scale and aesthetics.”