Down a narrow street in central Macao, close to Avenida de Almeida Ribeiro is the Lu Ban Carpentry Exhibition, dedicated to Lu Ban, a master carpenter, engineer and inventor who lived 2,500 years ago and is generally known as China’s patron of builders and contractors.

The museum, which opened in 2015, sits on the original site of a temple dedicated to Lu. Built in 1840, local carpenters would visit the temple before embarking on new projects to seek his blessing, bowing before his statue and burning incense. Twice a year, a Daoist priest conducted a ceremony at which food was distributed to the community in Lu’s name.

On the museum’s second floor, above the temple, is the office of the Macao Carpentry Trade Union (MCTU). In 2012, the union approached the government’s Cultural Affairs Bureau (IC) and proposed transforming the site into a museum. “We agreed with the carpenters that the history of the trade is a valuable part of the city’s culture and should be preserved and on display to the public. Currently, there are only a handful of carpenters left in Macao, and fewer young people want to enter the profession. We fear that one day there will be none left in the city,” says Daisy Chao Hong Peng, senior technician at the IC’s Department of Cultural Heritage. “We want to show people the traditional wisdom and skills of Macao’s carpenters. The exhibition is also a very informative source for research,” she adds.

The IC invested MOP5.2 million to restore the temple and pull together an exhibition displaying Lu’s inventions. The exhibition also contains donated tools from retired local carpenters. “We have been using and applying these carpentry tools and skills for thousands of years,” says Vong Heng Cheong, director of the MCTU. “We would like to conserve and introduce them to the next generation before the skills become extinct.”

A historical trade threatened

Carpentry is one of Macao’s oldest professions. “Historically, wood was the main material for buildings and furniture,” says Chao. Raw material imported from the mainland and neighbouring regions was then transformed into a myriad of structural and household goods, including pillars, beams and floorboards for houses as well as chairs, beds, tables and other pieces of furniture.

At the peak of the profession, during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), there were roughly 2,000 carpenters in the city. But, like with many professions, competition from the mainland following the open‑door and reform policy of the early 1980s forced wages lower. Easier and cheaper access to timber also drove profits down, and it became progressively more difficult for local carpenters to compete.

Districts like Dachong in Zhongshan, on the western side of the Pearl River Delta, have become international hubs of mahogany furniture production, supplying both the domestic market and exporting overseas. These industry centres possess economies of scale and new technologies with which Macao simply cannot compete. These days, the majority of Macao residents and developers purchase their furniture from suppliers across the border in Zhuhai.

Another factor in the decline of local carpentry is the variety of materials now used in the production of furniture, such as aluminium, steel, plastic and rubber, which has reduced the demand for wood furniture.

Currently, there are roughly 100 working carpenters in the city, all between the ages of 40 and 60 years old. Few young people want to enter a profession whose prospects seem bleak. To encourage a resurgence of the trade, the MCTU has been offering training classes. This training programme is actually one of the major inspirations behind the museum.

As the city’s carpenters have retired, many have gifted their tools to the union. Rather than storing them away in a forgotten cupboard to rust and gather dust, displaying them is a testament to their trade and might inspire future generations to carry on the craft. More than 80 items are currently included in the exhibit, together with audio‑visual and interactive components. These tools are not merely instruments for making a piece of furniture; they are imbued with the personality of their users, and many even bear the names of those who once wielded them.

The exhibit also includes reproductions of ancient tools, such as a pump drill once used to bore small holes and a chalk line used to mark straight edges.

The king of carpentry

If preserving the history and contribution of Macao’s carpenters is one theme throughout the museum, the life and inventions of Lu Ban constitute another.

Born around 507 B.C., during the Spring or Autumn period of the Zhou dynasty, Lu entered into a family of craftsmen. In his hometown of Jinan, today the capital of Shandong province, he was an average student until Bao Laodong taught him how to work with wood. Suddenly, Lu had found his calling in life. Applying himself to his studies with newly‑gained focus, he became an outstanding civil engineer and craftsman.

Throughout his 60 years, Lu dabbled in a wide variety of work. He was even employed by Emperor of the Zhu dynasty to work on military campaigns (records do not say which one). He is also credited with numerous inventions that have been used by carpenters across China and internationally throughout history, including the drilling hook, saw, chisel and drill, mortise and tenon, chalk line, stone grinder and mill, rulers and dividers. The current exhibit provides illustrations and explanations of these and other inventions.

The Lu Ban lock

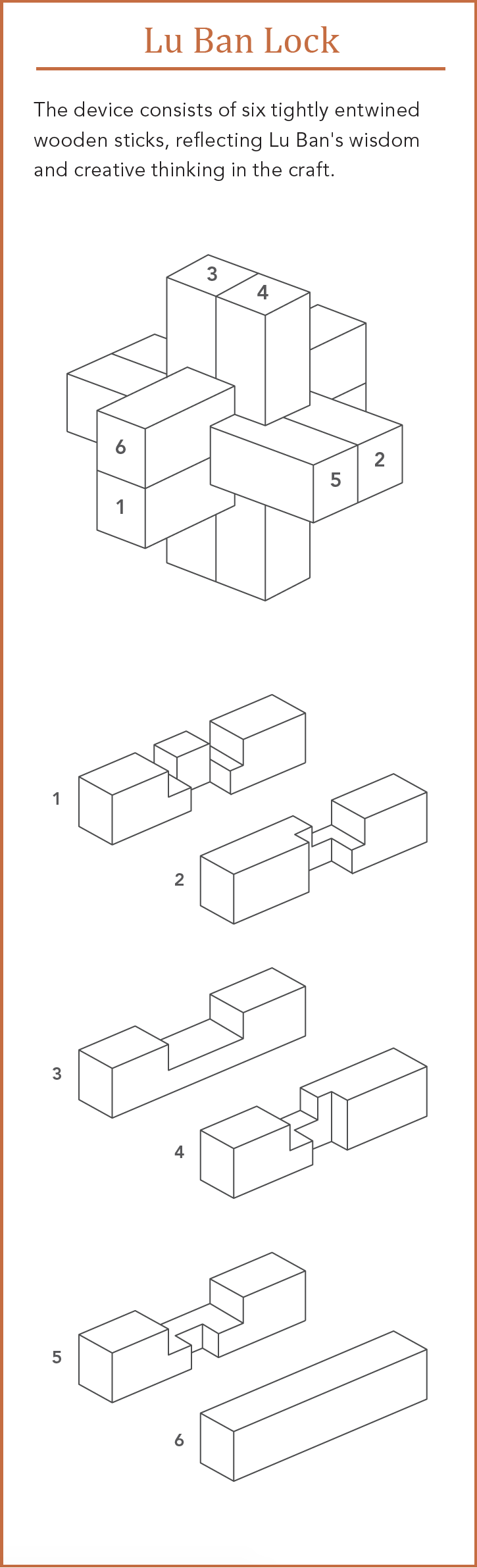

The largest piece in the museum, and arguably one of the most interesting, is the Lu Ban lock, which consists solely of several blocks of wood joined together. Quite easy to disassemble, it requires patience and understanding to put it back together. “There were no nails in Lu’s time, so he had to work without,” explains Chao. “Nails rust. So, if you do not have any, the pieces last longer.” Using a mortise and tenon technique attributed to Lu by some, a carpenter does not need nails; this particular technique is used throughout traditional, historic architecture. Toy versions of the lock are given to visiting children who are invited to reassemble it.

In 2014, Premier Li Keqiang presented German Chancellor Angela Merkel with a Lu Ban lock at an economic and technological forum in Berlin. “I hope the two countries can solve difficulties with intelligence and expand their future,” he added, acknowledging that while conflicts would inevitably arise over the course of the relationship, he looked forward to resolving them with the same patience and ingenuity required to assemble and reassemble the lock.

In China, Lu attained legendary status: woodworkers built temples in his honour, worshipping him like a saint. To this day, he is still considered the protector and patron of the profession. Festivals in his honour are held every year in Yunnan and Sichuan provinces, and many places (Luban waterway in Zhongsha island in Hainan, Luban strait in Sandui township in Sichuan, Luban township in Renhuai city in Guizhou, Luban lane in Chongwen district of Beijing) and buildings bear his name. The Chinese Architects Association bestows a Lu Ban Award annually for outstanding design (of buildings).

The Macao temple holds a ceremony, performed by Daoist priests, in his honour on the 13th day of the 6th month and the 20th day of the 12th month of the lunar calendar. Participants burn incense in front of his statue and prepare rice which is given to local carpenters and residents in Lu’s name.

A historic temple restored

The original temple, a single‑storey building, was constructed in 1840. In 1946, a second storey was added to house the MCTU.

The restoration work to return the building to its original state, carried out in 2013 by the IC, was no simple matter. The main challenges were damage due to dampness and deterioration of the brickwork. “We found the building to be very wet, with water coming up from the ground as well as dampness from the climate,” says Chao. “Water had come up the walls and some of the brick had decayed.” To draw the water out, the IC used an effective waterproofing method to remove excess water and salt buildup. Decaying bricks were also replaced and then waterproofed. Thanks to their efforts, residents and visitors alike can learn about the life of China’s master carpenter and the long line of craftsmen he inspired throughout history.

The museum attracts about 50 visitors a day, including organised tour groups. It is located on the Rua de Camilo Pessanha, off the Avenida de Almeida Ribeiro, the main street that runs through downtown Macao. Only a short walk from Leal Senado Square, the museum is easily accessible to tourists and is open every day, including public holidays, except Wednesdays. Admission is free of charge.