TEXT João Guedes

This year marks the 450th anniversary of the founding of Santa Casa da Misericórdia, the city’s oldest institute that offers social services to members of Macao’s society.

Afonso de Albuquerque, the great strategist of Portuguese expansion in the Far East, made it clear that Malacca was the final frontier for the crown he served. Anyone wanting to venture beyond that point could count on their own forces and ambitions, but not the caravels or the protection of Portuguese arms.

The stance taken by the grand admiral of the Indies helps explain some situations otherwise hard to understand nowadays. For example, the first Portuguese navigators to reach the shores of China actually arrived in junks bought or leased from Chinese merchants in the ports of Southeast Asia, not Portuguese vessels.

Macao’s Santa Casa da Misericórdia (Holy House of Mercy) was founded in 1569, more than a decade before a formal government, the Leal Senado, was established in 1583. The Jesuits (Society of Jesus) built Monte Fort and ensured that it was garrisoned with artillery and highly competent gunners, to judge from one shot by Father Jerónimo Ró (a doctor of mathematics who eventually served in the Beijing astronomical observatory), a direct hit against a force of Dutch invaders who fled the field in panic, never to return.

But the truth was just that: long before Macao became a national concern of the Portuguese Crown (which only appointed the first governor, Francisco de Mascarenhas in 1623), it was primarily a private initiative of merchants and the Jesuits.

For the far-ranging companions of St Ignatius of Loyola, Macao served as a base from which Japan and China could be won over to the Catholic faith. Safely ensconced in the Pearl River estuary, it was also a refuge and ideal location for trade, religious propagation and other operations in the delta region and the vast China Sea beyond, with its roving population of fugitive adventurers and pirates so well portrayed by Fernão Mendes Pinto in his 16th-century chronicle Peregrinaçao (Pilgrimmage).

It describes, for example, the Japanese smugglers who visited the annual fair in Canton (now Guangzhou) to trade silver, silk and spices, disguising themselves as Portuguese so the Chinese authorities wouldn’t realise who they were. That provides a possible explanation for some of the exotic countenances featured on Japan’s famous nanban screens. Indeed, the Middle Kingdom and the Land of the Rising Sun had broken off relations, and the Portuguese sought to benefit from the quarrel.

The profits were worth every effort, though it must be stated that the prevailing Wild West atmosphere was also marked by sudden reversals of fortune. That had happened to the early 16th-century trading community in Ningbo – the Liampó described by Mendes Pinto – which quickly achieved heights of grandeur but then paid a terrible price for its various abuses.

In just five hours, it was razed to the ground by imperial troops who rendered the harbour unusable and spared none of the nearly 300 Portuguese and allied families who lived there.

Similar incidents occurred elsewhere along the Chinese coast, auguring a black future for the Portuguese presence in these Oriental seas. One result was a plethora of destitute widows and orphans, a major concern for the Jesuits, who were otherwise more interested in organising and consolidating their continually imperilled presence in the Far East. They did not want to run the risk of establishing formal settlements that might similarly be swept from the map due to the all too frequent sins of pride, ostentation, and ignorance associated with the search for instant profits.

Revered caretaker, organiser

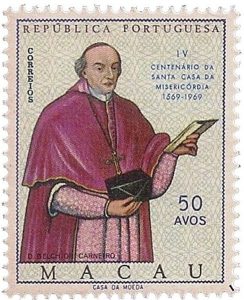

The aged and elegant building of Santa Casa da Misericórdia stands today in Macao’s main square, housing an institution that still pursues its original mission of protecting the poor and destitute. The reputation of this venerable institution is only rivalled by that its founder, the Jesuit bishop Dom Belchior Carneiro Leitão, who was tasked with overseeing the new Chinese diocese in the early years of its existence.

Carneiro is a major figure in the history of the Catholic Church in China, and not just for shepherding souls. Indeed, he shaped the political, administrative, social and religious structure of Macao so indelibly that even today his mark is felt, despite numerous social, urban, and political transformations over the last four and a half centuries.

Only a bare outline of this prelate’s life can be sketched as an in-depth study by a biographer has yet to appear, despite numerous citations over the course of history.

It is a known fact that he was born in 1516 in Coimbra, Portugal, and that after completing his education he became the first rector of the Jesuit college in Évora.

In 1555, Pope Julius III named him titular bishop of Nicaea (in modern-day Turkey) and coadjutor of Ethiopia; unable to travel there, he went instead to Macao to take charge of the nascent diocese of China and Japan. On the way, he stopped in Southeast Asia, informing its titular bishop that Malacca would no longer have ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the rest of ‘extreme Asia’.

When he arrived in the new Portuguese city at the mouth of the Pearl River in 1568, Carneiro wasted no time. A year later, he had gathered enough money and commitment to establish China’s first Western-style hospital. Originally known as Santa Casa da Misericórdia, its eventually became St Raphael’s Hospital before closing in 1974 (the building now houses the Portuguese Consulate).

At the same time as he was setting up the hospital, the bishop established a leprosarium in the neighbourhood now known as São Lázaro (St Lazarus). Leprosy was then an endemic illness; more than just killing its victims, it condemned them to abject poverty and social exclusion for the rest of their lives, making no distinctions for class or ethnic group.

-

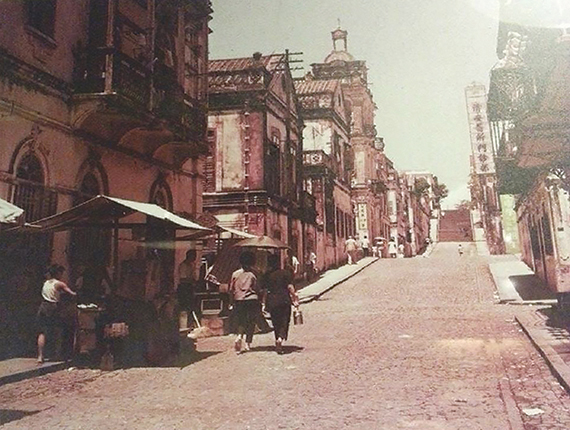

São Lázaro neighbourhood then | Photo by António Sanmarful -

São Lázaro neighbourhood in 2019 | Photo by António Sanmarful

The hospital, which began as a small dispensary that attended to all comers, was called I Yan Miu (Temple of Cures) by the Chinese. Much later, in the early 19th century, it would implement the first smallpox vaccination programmes in China.

Once Santa Casa’s inherent tasks of caring for people who were ill, poor, destitute or needy (as well as widows and matters involving the deceased and the absent) were consolidated, Carneiro began to pressure the citizens to organise themselves politically.

He insisted that a government was indispensable for guaranteeing order and social cohesion in the face of anarchy and chaos. The memory of Liampó was still fresh in mind; he claimed it had been caused by the lack of a government to check base instincts and prevent the kind of behaviour that inevitably leads to disaster.

The citizens accordingly established a form of government resembling the systems then used in Italian republics; others claimed similarities with the “cities of the Kingdom and of the State of India.” This question has yet to be given sufficient academic attention.

The Leal Senado was thus headed by two ordinary judges and three councillors elected by the most influential residents. For the next 45 years, Macao would be governed by the council of the Leal Senado, which would also represent Portugal before China.

Dom Belchior Carneiro Leitão died in Macao on 19 August 1583, following an asthma attack that the best physicians from St Paul’s College were unable to alleviate. He was 67 years old. The facts of his life outlined above are a matter of historical record; however, his crucial role in the territory’s early days is based more on tradition than academic rigour.

That tradition is indisputable: in the following centuries, a reliquary made of precious wood containing the skull and bones of Carneiro was placed on a table before each meeting of the confraternity of Santa Casa.

That ritual, which fell out of use in the 20th century, demonstrates how far his memory was revered. Whether he actually accomplished everything attributed to him is an open question. Indeed, his activities began to be questioned soon after the arrival of his successor in the diocese, Dom Leonardo de Sá, who was an apostolic inquisitor committed to purifying the faith of China’s Christians by fire if necessary, with no toleration for heterodoxy of any kind in religious matters.

When he arrived, many of Macao’s Portuguese residents were New Christians (converts or descendants of converts from Islam or Judaism in recent times). There were also Jews who practiced their faith openly, protected by the Jesuits, who counted numerous converts among their own members and sought to prevent any expansion of the Inquisition to Macao. They were able to resist, because the Society of Jesus was beyond diocesan control, solely and directly obeying the Pope. That helps explain the exalted role that tradition attributes to Carneiro, as opposed to the reservations of recorded history. Given the many lacunas, only new studies can shed light on the life of one of the most brilliant Portuguese Jesuits, an outstanding figure in the history of Macao.

Changing role in a changing city

Internal bickering about the question of rites would occupy the Macao Church in its early years, pitting those who defended acculturation (the Jesuits) against those who rejected any deviations from orthodox Catholicism (the Dominicans).

The controversy eventually led to the expulsion of the Company of Jesus and a failure of the Jesuits’ plan for China. But the power and prestige of Santa Casa da Misericórdia, the Holy House of Mercy, remained solidly intact.

Their close association with the Leal Senado meant the two were often confused; at times, the leaders of one institution headed the other as well. That circumstance was decisive for consolidating the financial structure of Santa Casa, to the point that it became a major banking institution of high repute in not just Macao but also the Philippines, Siam (now Thailand) and points beyond, with its fame even reaching the major financial centres of India.

That vigour eventually transformed the institution into a veritable bank which lent and managed fortunes, due to its role defending the assets of the deceased and absent. During a time marked by difficult and slow communication between Lisbon and the empire’s various capitals, Santa Casa thus became a faithful depositary of the inheritances of those who died in Macao without descendants, or those lost at sea.

Shipwrecks were frequent and each vessel that disappeared left dozens of family members without support, mainly women and children whose assets were managed by Santa Casa. There were also voluntary donations; perhaps the most famous was from Marta da Silva Van Mierop, a figure whose full-length oil portrait still occupies a prominent place in the main hall of Santa Casa.

The institution eventually began financing the fleet owners who launched the major maritime trading ventures. That naturally led Santa Casa to expand its interests to insurance activity, with the consequent creation of the Casa de Seguros de Macau (House of Insurance of Macao) in 1797.

But the high expectations generated by that company were actually the result of a financial bubble, to use today’s wording. It soon went bankrupt and its funds, like ships in a storm, were also lost, giving rise to the legend of the ‘Calcutta millions’ that writer and journalist José Campos e Sousa describes in one of his books, printed in 1936.

Over the course of the 19th century, Santa Casa gradually became involved in dubious ventures; its virtual disappearance from the marketplace would end the focus on financial matters. The crisis was aggravated by political changes resulting from Portugal’s Liberal Revolution of 1820.

The Crown began playing a more active role in Portugal’s social protection and health sector and Macao was naturally affected. From the period of Governor Ferreira do Amaral (1846–49), the Leal Senado was transformed into a government secretariat and the local business elites were distanced from power and lost interest in Santa Casa, which then had to struggle with an increasing lack of brothers. That situation lasted until 1905, when the local government granted itself the right to name the director, who would be aided by three assistants elected by the confreres.

Santa Casa was nevertheless able to ‘keep in step’ with the times, maintaining its care-related activities, particularly during the War of the Pacific (1879–1883), when Macao was forced to deal with a veritable flood of refugees that doubled the population.

The social support provided by the institution was only possible because, unlike all the other Catholic confraternities, it never limited its activity to mutual aid between members. Rather the contrary: from the very beginning, it was always open to all those in need. Santa Casa de Misericórdia, ever mindful of its Catholic and Portuguese underpinnings, remains an intrinsic landmark of Macao. In 2005, the building became part of the Historic Centre of Macao, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Modern relic

This year marks the 450th anniversary of Santa Casa da Misericórdia’s founding, and although the institution has undergone multiple evolutions in its long history, its guiding mission remains the same: compassionate care and charity responsive to the issues of the time, be it leprosy or shipwrecks or the challenges facing Macao people today.

Challenges like child and elder care, but opportunities as well – provided people have the support that they need. Santa Casa plans to offer that support and help to Macao residents looking to participate in the Greater Bay Area development, and to extend its social services via the Belt and Road Initiative.

It serves a cohesive role as well, bringing together Macao’s Portuguese residents, especially the Macanese, and helping to promote cultural exchanges and maintain Portuguese-Chinese friendship. This cross-cultural bridging, along with its welcoming of all people, regardless of race or religion, continues to contribute to the harmonious development of the city.

As leaders from the government and Santa Casa itself gathered to celebrate the 450th anniversary on 15 May, they were unanimous in their praise for the past – and in their hopes for the future of Macao’s oldest social welfare and charity institution.

An everlasting commitment

The Holy House of Mercy has continued its work caring for the needy in part by shifting to a modern, outreaching approach. This May, the institution became a first-time host of the International Congress of the Houses of Mercy, welcoming representatives of the Houses of Mercy in South America, Africa, and Europe to the city to explore issues of social welfare and medical policies.

The Macao institution is the last remaining Holy House of Mercy in Asia, with those in Japan, Korea, and Thailand closing down due to financial and political issues. Macao’s Holy House of Mercy currently boasts 350 active members and provides a wide range of charitable services through its non-profit facilities such as the Creche, a day-care centre for children; Our Lady of Mercy Home for the Elderly; and the Rehabilitation Centre for the Blind.

Promoting cultural industries is another area where it contributes, offering space in its old Albergue of the Macau Holy House of Mercy to local arts and cultural associations. Originally a sanctuary for elderly women, the 100-year-old Portuguese building has become a popular venue for exhibitions, workshops, and cultural events.

Its operating budget of more than MOP70 million (US$8.63 million) comes from multiple sources, including rental income, substantial corporate contributions and government subsidies, which account for about 25 per cent.