Whether they’re fleeing a revolution, looking for decent domestic work or even preparing to launch a Grand Prix, Indonesians have been migrating to Macao for more than half a century. Welcome to a vibrant community that has been integral in building our city.

When it comes to China’s SARs, Hong Kong is usually championed as being the multicultural melting pot. However, Macao should not be forgotten as it is also home to an incredibly diverse mix of cultures. Out of the 658,900 people living in the city, a total of 193,470 are classed as non-permanent residents. And out of these, the biggest group is the Mainland Chinese – 62.3 per cent of all non-permanent residents. Next comes Filipinos – 17 per cent – and then the Vietnamese at 7.7 per cent. But how many Indonesians do we have here? The answer: a lot more than you would perhaps expect.

Macao’s Indonesian community makes up three per cent of all non-permanent residents, which may not sound much but that’s actually around 5,761 people. And that doesn’t include the thousands more with Indonesian heritage who are permanent residents, some of them descendents of families who have lived in the city for generations. The Indonesian community is an important backbone to Macao and we can see this colourful culture across the city, from the restaurants to the domestic helpers.

Two distinct groups form the Indonesian community – those who’ve been in Macao for a number of generations and those who have come in recent years as economic migrants. Those who have been here for years are often ethnic Chinese who left Indonesia in the 1950s and 60s when it gained independence and underwent restructuring. Due to anti-Chinese sentiments, Chinese-Indonesians became targets of violence, with many being forced to remain as Indonesian citizens. There were limitations set on their businesses, making it illegal for non-indigenous people to trade in rural areas. Indigenous Indonesians – or ‘Pribumi’ – were seen, at the time, as more important to groups like Chinese-Indonesians, who had once been granted privileged economic and social status under Dutch rule. Because of growing negative feelings towards this subgroup – as well as the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 – many youths chose to leave for China. Many of them came to Macao.

Speaking our language

One man who came to China in the 1950s is the president of the Executive Board for the Macao Association for the Promotion of Exchange between Asia-Pacific and Latin America (MAPEAL) and polyglot – he speaks 13 languages – Gary Ngai Mei Cheong. Born in 1932 in Semarang, the capital of Indonesia’s Central Java province, to a sixth generation Chinese-Indonesian family that originated from Fujian province in southeast China, Ngai’s background personifies Macao’s Indonesian community – multicultural and diverse.

With a knack for learning languages since boyhood, Ngai easily picked up Dutch from his father and teachers, then Mandarin and Javanese from his mother. He also learned English and Japanese in school, as well as Bahasa, which became the national language after Indonesia gained independence in 1945. When the PRC was established in 1949, however, Chinese communities abroad were full of feelings of patriotism, with the teachers in Ngai’s Mandarin-based secondary school encouraging students to return to the ‘motherland’. He was inspired and left for China in 1950 despite some of his greater family opposing his decision.

Ngai soon wound up in Beijing and it wasn’t long before he was being trained as an interpreter due to his linguistic skills. He graduated from Renmin (People’s) University in 1956 and then worked as one of the country’s senior interpreters for leaders like Peng Zhen and Deng Xiaoping. He even translated for the PRC’s founding father Mao Zedong, an experience he says felt ‘normal’ due to the sheer amount of other interpreters who would all work simultaneously. At this time, he also learned French, German, Italian, Swedish, Norwegian and Danish on his own, translating in those languages as well, through the guidance of native language experts and self-study.

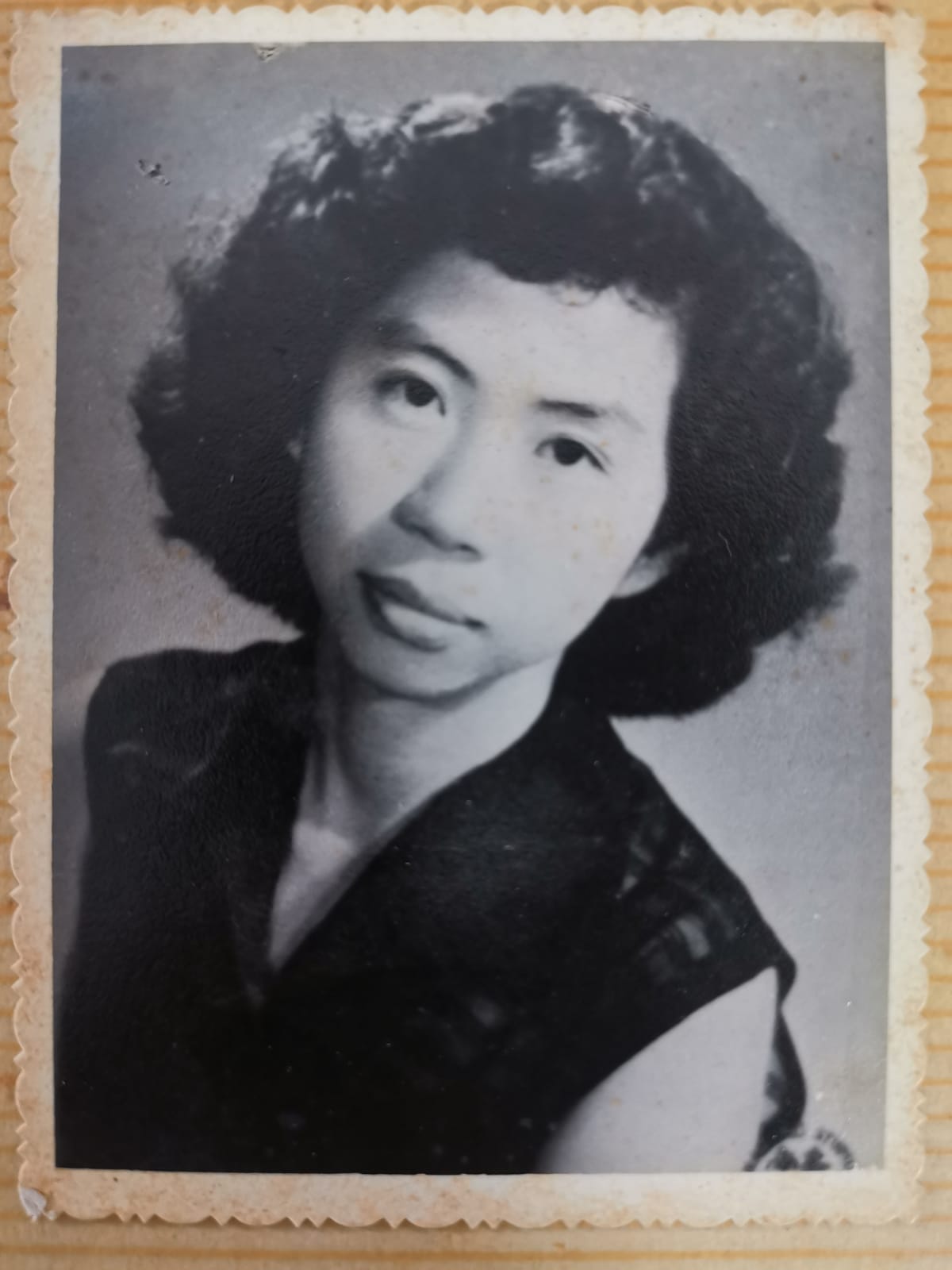

In 1961, Ngai married Molly, an Indonesian-Chinese woman from the capital of Indonesia’s North Sumatra province, Medan, who, in 1951, also moved to China. Earning only small wages every month until 1979, the couple found it difficult, especially when Molly fell pregnant. “She hardly had any milk,” says Ngai. During the Cultural Revolution, between 1966 and 1976, the family spent four years living in Heilongjiang, China’s northernmost province, in a cowshed, braving harsh winters.

Ngai’s mother-in-law escaped to Macao after the anti-Chinese riots in Indonesia in 1965 and 1966. In 1978, his wife and two children joined her – she joined the Overseas Chinese Association of Macao, an organisation Ngai became an advisor for – in the city to look after her. He joined them later, aged 47, facing a new life. “It was hard at the beginning,” he says. “Macao was a small place and I could not find a job.” However, Ngai, ever the linguist, soon learned Portuguese and Cantonese.

Chinese-Indonesian people are one of the forces that built Macao.

Ngai’s first job, however, was at public broadcaster TDM as a translator in the newsroom, eventually working his way up to the role of deputy director of programmes for its Chinese radio channel. He also became a technical adviser to Macao’s last governor, Vasco Joaquim Rocha Vieira, in the period running up to the 1999 handover of administration. As part of that role, he compiled the Chinese news every day, giving Vieira and the Portuguese government local perspectives.

“I do not regret my decision to go to China,” says Ngai, who has been a pillar of the community in Macao for many years, with roles such as associate director of the Cultural Affairs Bureau, founder of the Macau Sino-Latin Foundation and vice-president of the now defunct Macau Social Sciences Association all under his belt, among many other high profile positions. “On the positive side, I really understood China from the top to the bottom and I made a contribution to the new state. On the negative side, we suffered a lot. I never considered moving back to Indonesia, where I have many relatives. Anti-Chinese sentiment remains and what could I do there?”

“Being an Indonesian-Chinese,” continues Ngai, “we’ve been trying our best to keep our cultural identity, which contains excerpts of both cultures.” He describes Macao as having a unique identity to those of its neighbours – ‘Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Shanghai and other Chinese cities’ – a point where East meets West, with a bridge to Latin-speaking countries as well. “It is a city not only of gaming but of culture,” he concludes.

Food, glorious food

Another couple of Indonesians who also personify Macao’s Indonesian community are the founders and owners of the popular Medan Indonesian Restaurant on Rua de Marques de Oliveira in St Anthony’s Parish. Sisters Lee Kam Chi and Lee Iok Pui – who are 13 years apart in age and didn’t grow up in the same house together – left Indonesia for China in the 1960s, both prepared to never return to their homeland, leaving their families behind them.

Lee Kam Chi is now 94 years old and her sister is 81 years old – but they still have a hand in their restaurant, whose most popular dishes include ‘nasi kuning’ – assorted yellow ginger rice – and ‘nasi uduk’ – assorted pandan rice – as well as the classic Hainan chicken rice. However, it hasn’t been an easy road for the siblings. When they arrived in China, Lee Kam Chi worked as a maths and Chinese teacher in Foshan, while Lee Iok Pui studied at Jinan University for a degree in mining and geological engineering. After she graduated in 1962, she joined her sister in Foshan.

When the Cultural Revolution began and the political environment in China became unstable, Lee Kam Chi decided to come to Macao alone to seek new opportunities. After she found a small place to stay in, her brother arrived to join her with his two children in tow. Lee Kam Chi tried her hand in different sectors like teaching, accountancy and even tailoring but all didn’t work out because she couldn’t speak Cantonese at that time. However, when she was younger and still in Indonesia, she liked being in the kitchen to observe meals being prepared. Chefs liked her curiosity and enthusiasm to learn, so they taught her.

Lee Kam Chi, therefore, decided to play to her Indonesian roots and open a restaurant in Macao. Medan, named after her hometown, was born on 2 September 1972 at 20 Rua de Silva Mendes. It wasn’t easy, though – Macao was home to many Indonesian restaurants at the time, so the industry was fiercely competitive. Lee Kam Chi was also new to the city and couldn’t get the help she needed, so she had to settle with Medan being a self-service snack store until 1974. In 1975, however, her sister joined her from Foshan, where she had been working as an administrator, and together the sisters moved their store to Avenida de Horta e Costa in 1976, launching the full-blown restaurant and bringing with them their distinctive Indonesian flavoured desserts and pastries.

At the time, Lee Kam Chi’s nephew Lee Chi Kan – one of her brother’s sons – was only seven years old. As he recalls, while growing up, he and his fouryear-old brother would help at the restaurant when they had no classes, waiting on customers and manning the cash register. But the hard work of cooking and creating the dishes went entirely to the two restaurant owners, with Lee Iok Pui also on the day-to-day operations and customer relations, and Lee Kam Chi responsible for production and quality management.

When the sisters first launched Medan as a restaurant, most of its customers were fellow ChineseIndonesians. But as the eatery grew in popularity, the sisters slowly began to see a steady stream of locals chowing down on their dishes. They say that some locals began to come in three or four times a week. As they were conveniently located near a number of schools, many of the sisters’ customers were also students. Many students based overseas today also continue the tradition of visiting Medan as soon as they arrive back on home soil for the flavours they missed while they were away.

“It wasn’t easy when I first started the business,” admits Lee Kam Chi, who, along with her sister, has lived in Macao ever since the launch of her restaurant. But, she says, through the support of the restaurant’s customers and Lee’s own growing family, they were able to succeed. She says that, at the beginning, she only paid about MOP 150 a month during the 1970s to cover the restaurant’s rent. However, she notes that, obviously, that cost has risen dramatically over the years – adding, she says, to the challenges of owning a restaurant without actually owning the property. But, she concedes, over the eatery’s 47 years and through countless hardships, the shop has survived and become an indispensable part of the community, familiar to both new and old Indonesians in Macao.

Here’s Johnny

Johnny Sitou, chairman of the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce Macao and vice-president of the Association of Returned Overseas Chinese Macau, was one of the people behind this year’s Indonesian Culinary and Cultural Carnival – the first festival of its kind in the city, attended by hundreds of people. It was a colourful – and tasty – affair that served to champion not only Indonesian cuisine but the city’s Indonesian community. Held near the Taipa Houses Museum between 20 and 23 September, the event – jointly organised by the Association of Returned Overseas Chinese Macau and the Indonesian Consulate General in Hong Kong and Macao – saw residents and visitors experiencing the best Indonesian food, as well as live music and dance, and stalls including Indonesian art and crafts.

Sitou has an interesting story behind him. His entire family fled to Macao from Indonesia in 1965 and 1966 when he was just three years old. They had to flee because his father was a personal assistant to the then President, Sukarno, who was put under house arrest in 1967 following the mid-60s political turmoil before dying of kidney failure, still under house arrest, in 1970. In the few years leading up to 1967, the situation was too dangerous for Sitou’s family, so they had no choice but to take flight. According to Sitou, this was an incredibly difficult time for his father because he had been used to holding a high position in the Indonesian government. The family were also unable to take any money with them when they fled for Macao. This took a mental toll on Sitou’s father but, after a time, his dad started a business and ‘the situation got better’.

“During the 60s, many [Indonesian immigrants in Macao] became taxi drivers,” recalls Sitou. “Some of them also opened restaurants and some of them worked in the construction business.” Sitou says his family’s situation was not unique, as many Chinese-Indonesians went through a similar ordeal. However, he notes these people gradually became integral to Macao society as a whole.

Newcomers to the domestic scene

In more recent years, Macao’s Indonesian population has grown due to the influx of domestic helpers from the country, many who arrive on limited-term contracts. Unlike before, these new migrants mostly come from Java and Sumatra – and they are not of Chinese ethnicity. Macao’s Indonesian domestic helpers used to be a vulnerable community as there were few places to go with complaints or to get support due to the fact there was no local Indonesian consulate.

Macao’s Peduli – Indonesian Migrant Workers Concern Group was created in 2004. It is one of three organisations supporting Indonesian migrants and their rights in the city, alongside the Indonesian Migrant Workers’ Union, created in 2008, and the Jaringan Buruh Migran Indonesia, created in 2018. As George Young – one of Peduli’s founders – shares, the word ‘peduli’ simply means ‘care’, as the organisation was created to provide support for Indonesian migrant workers who may be experiencing problems, like passport troubles. Since there was, until fairly recently, no guarantee of protection due to the absence of an Indonesian consulate, Peduli stepped in whenever it could to dissipate any conflicts or to protect the migrants.

However, when the Indonesian Consulate General in Hong Kong also began to serve those workers in Macao in January 2017, Peduli’s function from mediator morphed to that of community builder, occasionally performing at local events when invited. Ari Widyawati, one of Peduli’s traditional dance performers, notes how grateful they are when receiving invitations to perform at events, usually practicing three times a week. “We finish our work at 9pm,” she says, “and we take a rest for one hour. So we have practice at 10pm until 12 midnight.” If the dances aren’t ready, says Widyawati, they find more time to practice.

The traditional dancers also gather for big Islamic festivals like May’s Eid al-Fitr, also called the ‘Festival of Breaking the Fast’, the holiday that Muslims celebrate to mark the end of Ramadan, and July’s Eid al-Adha, also called the ‘Festival of the Sacrifice’, an Islamic holiday honouring the willingness of Ibrahim to sacrifice his son as an act of obedience to God’s command. They celebrate with other ethnic groups at the Macau Mosque – the only mosque in the city – in Ramal Dos Mouros. In Macao, there are five purely Indonesian Muslim groups – Halaqoh, Matim, YPW, Irsyad and Jemaah Masjid. Peduli president Siti Romlah Jamat – also known as Jus Jus Romlah – says the association has existed for 10 years, with their birthday every year coinciding with Indonesian Independence Day on 17 August.

A community to celebrate

The influx of domestic helpers has only further strengthened Macao’s Indonesian community. And the community was certainly on full show at September’s Indonesian Culinary and Cultural Carnival, an event that brought many Indonesians together, some even shocking each other when they found they shared the same heritage.

One man who attended was Gilbert Humphrey, better known as Beto Bebeto, the host of Macao’s only Indonesian radio show, TDM’s ‘Kumbang Toh!’ programme. Humphrey comes from excellent Indonesian stock, his great-grandfather being the driving force behind the Macau Grand Prix, the late Theodore ‘Teddy’ Yip Tak Lei. Teddy Yip, who was instrumental in developing the city as the tourist destination it is today as well as being a Formula One team owner in the 1970s and brother-in-law to gaming magnate Stanley Ho, was born in Medan with Hakka ancestry but arrived in Macao in the 1940s. His legally adopted son Willy Yip Hing Wah – also Yip’s biological nephew and Humphrey’s grandfather – was invited to move to Macao in the early 1960s. As a result, Willy Yip moved his whole family to the city from Indonesia and helped grow their family business.

Humphrey took the time at the carnival to seek out Lee Kam Chi so they could swap stories about their families over the generations in Macao. Lee Kam Chi also showed off her restaurant’s cuisine to visitors during the event and she and her family also received praise from Sitou during the carnival’s opening ceremony for Medan as it is Macao’s longest standing Indonesian restaurant.

“I would say [ChineseIndonesians] are one of the forces that built Macao,” said Sitou at the start of the carnival. He likens them to ethnically Chinese immigrants from Myanmar and Cambodia, who similarly came to Macao in the 1950s and 60s during politically tough times in their homelands and who also contributed greatly to Macao’s growth and development. “So many Chinese people chose to leave their countries,” he concluded, “and settle down either in China, Macao or Hong Kong.”

The carnival showed off Macao’s Indonesian community to the public – and it showed how colourful, lively and important it is to the city. Organisers hope it will become an annual event, so every year locals and tourists alike can discover one of the city’s most important ethnic communities. A community that brought you a restaurant like Medan, a radio programme like ‘Kumbang Toh!’, the city’s famous Grand Prix and a host of people who are committed to protecting and preserving their culture for future generations to come.

Indonesia: the facts

Number of Indonesian non-permanent residents in Macao in 2008

3,478

Number of Indonesian non-permanent residents in Macao in 2019

5,761

Population of Indonesia in November 2019

271.7 million

Percentage of the country that is Muslim

87.1%

Percentage of the world’s Muslim population living in Indonesia

12.6%

World ranking in terms of population

4th biggest

Official language

Bahasa Indonesia (However, more than 700 languages are spoken in Indonesia, including English, Dutch and local dialects like Javanese)

Big Indonesian festivals

Eid al-Adha and Eid al-Fitr, plus Nyepi, the Day of Silence, in Bali

The day Indonesia became an independent country

17 August 1945

National dish

Nasi goreng

National bird

Elang jawa

(the Javan hawk-eagle)

Flag colours

Red over white

Bahasa Indonesian for ‘I love Macao’

‘Aku cinta Macau’