The government’s draft urban master plan for the development of Macao over the next 20 years was unveiled in early September. Ahead of next year’s final document, we speak with the experts and break down what plans are being proposed for the city by 2040.

In early September, a document was published by Macao’s government that quite literally will change the face of the city over the next 20 years. The long-awaited new Urban Master Plan was released in draft form, kicking off a 60-day public consultation period that started on 4 September and ended on 2 November. It was an important moment in the history of the SAR and, once the public’s views have been digested and the plan is finalised next year, it will define how Macao will develop between now and 2040.

The new draft Urban Master Plan which we shall call the master plan from here on was launched by the government during a special press conference. It’s a plan that’s been in the pipeline for almost six years and it proposes that Macao be divided into clearly defined areas such as residential, tourism, green leisure and industrial. It also prioritises habitation and public infrastructure developments, and estimates that by 2040, the city’s population will reach 808,000 from the around 650,000 it stands at now. It also expects the city’s total land area to go up from today’s 32.9 square kilometres to 36.8 and labels percentages of the land to different categories, such as 23 per cent for public infrastructure and 22 per cent for residential purposes.

Ever since it was launched a few weeks ago, experts have praised large parts of it for its forward-thinking. Some say that there needs to be more detail in there but they consider it ‘an essential document’ for the future of the SAR, adequately setting the guidelines for the city’s future development. So what lies within the pages of this crucial planning document and what do the experts think about it?

Open plan

One of the most important goals of the master plan is to improve the quality of life for all of Macao’s residents over the coming years. The plan introduces groundbreaking concepts for the city’s future development, such as the division of the Macao SAR into defined areas for residential, tourism, green leisure, industrial and diversified industries purposes, with housing and public infrastructure development having priority. This city-zoning is highlighted as ‘crucial’ by architect and urban planner Nuno Soares, a member of the Architects Association of Macau’s board of directors – a sentiment shared by Alfred Seng Fat Wong, associate professor of the electromechanical engineering department in the University of Macau’s Faculty of Science and Technology.

The master plan proposes that Macao’s land will be divided into eight designated zones. A total of 22 per cent of the land will be for residential use and 23 per cent will be for public infrastructure. A total of 18 per cent will be for ‘ecological conservation’, 13 per cent will be for tourism and entertainment, 10 per cent will be for public facilities, eight per cent will be ‘green areas’, four per cent will be for commercial use and, last but not least, the remaining two per cent will be for industrial use.

Soares is the founder and principal architect at local firm Urban Practice, as well as both the architecture programme co-ordinator at the University of Saint Joseph and founder and director of Macao-based non-profit organisation CURB, which stands for the Centre for Architecture and Urbanism. He emphasises that, in the master plan, ‘there is a principle of organising the territory into areas’ and that each of these areas ‘will have its existing character reinforced’. “I think it will be greatly advantageous for people to live in neighbourhoods that will have a less generic and more idiosyncratic character,” he says. “This is one of the key strategies of the plan and I believe it’s a good principle.”

Experts have emphasised the relevance of some of the land use principles and spatial distribution announced by the authorities that are intended, amongst other things, to optimise the balance between employment and housing areas. The government has introduced this principle in an attempt to weigh up the development between the peninsula and the islands, as well as to reorganise the city so that residents have fewer transportation needs, thus reducing time-consuming trips between home, work and school, and decreasing traffic pressure and the need for parking spaces. The plan also proposes the safeguarding of 21 visual corridors – fixed envelopes of space that must be unobstructed to the sky – to help protect the views of the Historic Centre of Macao as well as to preserve Macao’s ‘mountain, sea and city’ relationship.

The government’s Land, Public Works and Transport Bureau (DSSOPT) entrusted Hong Kong company Ove Arup & Partners with the preparation of the plan, which covers the Macao Peninsula, the islands of Taipa and Coloane, the city’s new landfills, the checkpoint on the artificial island of the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge (HZMB) and the 85 square kilometres of maritime area under the jurisdiction of Macao. The public consultation on the plan lasted for 60 days and, following this process, the final document is expected to summarise the views expressed during the consultation. It will also include opinions from the Urban Planning Council (CPU) and a final report will be drafted by the DSSOPT and submitted to Chief Executive Ho Iat Seng by next September.

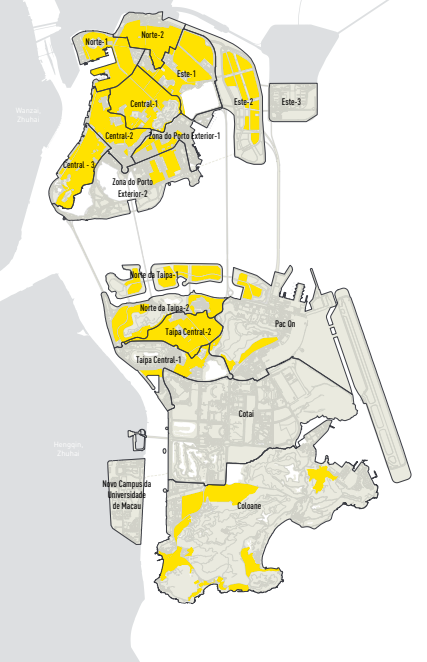

The master plan establishes the positioning of Macao’s urban development not just locally and regionally but nationally too. It looks at the further integration of the city into the Greater Bay Area (GBA) – the ‘megalopolis’ zone in the south of the country that’s made up of nine cities and the Macao and Hong Kong SARs – and China as a whole. It also divides the city into 18 planning districts, including in the North, Eastern and Central districts, as well as in the Outer Harbour, Taipa, Cotai, Colane and the University of Macau (UM) New Campus districts. Each one of these zones will have a specific development plan tailored to them in the future.

The plan aims to promote Macao’s development in tandem with the GBA and to maximise the geographical advantages of nearby Zhuhai and Hengqin Island – as well as the opportunities offered by the new HZMB – by balancing the development of the city. Four ‘belts’ of development are assigned to Macao in the plan – the ‘Historical Coastal Area’ belt, the ‘One River, Two Margins Co-operation’ belt, the ‘Knowledge, Industry, Science’ belt and the ‘Resilient Green’ belt. These belts speak for themselves, however the ‘One River, Two Margins’ belt is part of plans for deeper co-operation within the GBA. It covers an area where urban developments will be based on transport network expansions for a plethora of reasons including the goal for people to travel between Macao and the main cities in Guangdong province within an hour.

Putting the housing in order

The master plan proposes that residential areas will account for 22 per cent of Macao’s total land area. This is a five per cent increase from the current 17 per cent and shows how important the issue of housing is for the government over the next 20 years. Macao’s population is predicted to rise by more than 150,000 people by 2040 so the proposed increase in housing is intended to satisfy the demand for accommodation by the new population.

Soares labels the plan’s drive for more economic and social housing as ‘positive’. He also picks up on the way the plan treats housing in the city as a whole and the environment that surrounds the housing zones. He says: “The master plan introduces a general improvement of the urban space, which will bring benefits to different residential areas. We will have more green areas and we will have a better-organised transport network. All of this will bring advantages to these residential areas and I think those are aspects that are objectively expressed in the plan and that will contribute to an improvement in the housing field.”

New land reclamation areas had already been announced prior to the master plan, however, they are also obviously an important part of it. There are five main newly reclaimed land sections in the city, with housing for around 162,000 residents planned on some of the land. The largest piece of land – Zone A, an artificial island of 1.38 square kilometres that’s connected to the Macao terminal of the HZMB – is expected to accommodate some 32,000 housing units in the future, with 28,000 of them to be used for public housing.

The master plan introduces a general improvement of the urban space, which will bring benefits to different residential areas. We will have more green areas and we will have a better organised transport network.

– Nuno Soares

With all this extra housing comes the headache of making sure that the density of the residential areas is balanced across the SAR and that traffic problems don’t occur as a result of any imbalances. The plan addresses this. According to the government, there are, on average, about 20,000 people per square kilometre in Macao, with the local population mainly concentrated in the northern part of the peninsula and in downtown Taipa. But the plan notes that areas like Horta e Costa and Ouvidor Arriaga are about 4.5 times more populated than the average and a couple of neighbourhoods like Tamagnini Barbosa, Areia Preta and Iao Hon are up to seven times the average. Notably, these districts are all on the peninsula in northern Macao and yet many of the jobs are in the entertainment resorts which are in and around Cotai on the island in the south of the city, thus resulting in an urban distribution with ‘residential areas in the north and jobs in the south’. The situation creates a daily north to south pendulum traffic movement – but the urban master plan addresses the issue.

Interestingly, the issue of the Zone A land reclamation area and possible traffic problems came up on 4 November during a session where the government briefed lawmakers about the master plan. In the meeting, Secretary for Transport and Public Works Raimundo do Rosário said that the authority aimed for the construction of some 23,000 public housing units to get off the ground by 2024. He admitted that Zone A would be a densely populated area where about 100,000 residents were expected to live, adding that therefore a traffic issue in the area – and its traffic links with the rest of the city – could be expected. He said the government will need to tackle this issue as efficiently as possible.

The master plan says that the use of land in residential areas is expected to be compatible with other purposes, such as commerce and community equipment for collective use. Schools and other educational facilities also come under this, as do cultural and health facilities, to ‘improve the quality of life for citizens and create a livable community’, according to the plan. In fact, commercial areas come hand-in-hand with some of the housing areas, although the plan does also highlight that the total ratio of commercial areas will increase from the current one per cent to four per cent of the city’s total land area. On top of this, there will also be urban renewal works prioritised in areas with a larger concentration of older buildings and a higher population density, starting with the Tamagnini Barbosa, Areia Preta, Iao Hon, Horta e Costa, San Kiu, Conselheiro Ferreira de Almeida and Ferreira do Amaral neighbourhoods.

In order to create conditions for people to work in the areas where they live – as well as to create more job opportunities overall – the plan also proposes the development of more commercial areas on the Macao Peninsula. This includes plans for commercial zones at the Border Gate, on the artificial island of the HZMB checkpoint, in the Zone A reclaimed area and on the east side of the Zone B reclaimed area. In addition, more housing areas will be developed in newly reclaimed areas in Taipa and Coloane, such as in the Zone C reclaimed area and in the vicinity of the village of Cheok Ka and Seac Pai Van. In short, all of these plans show the emphasis the government is putting on creating conditions for people to be able to work in the areas in which they live.

While the master plan creates ‘non-urban’ areas and doesn’t allow construction in protected areas – such as the hills of Coloane Island, Barra and Penha – the document also shows an increase in the amount of land allocated to construction works in Coloane. For instance, the plan shows that Alto de Coloane – the highest point of Macao at 172.4 metres above sea level – will see a cluster of residential buildings constructed on its slopes. This includes high-rises as well as standalone housing – and this has raised some concerns across the city. Soares considers that the dimension and density of the area designated for construction is not appropriate for Coloane, which is partially classified as an ecological conservation area.

On a map that defines the use of each plot of Macao’s future 36.8 square kilometres, the Alto de Coloane area appears in yellow, which means it is destined to be a residential area. “It’s probably not yet very detailed,” says Soares, “but what we can see in the master plan consultation document is worrying because it shows a large increase in the construction area, with a typology that is dense and not adjusted to the surrounding urban context.” Soares refers to the proposed expansion in the construction area in Coloane village and Alto de Coloane – however, during a September meeting, Raimundo do Rosário flagged up that detailed plans for the proposed projects, which would address concerns over any negative effects of the schemes, will follow the master plan.

Despite some criticism over certain housing projects in the plan, many people in the city have welcomed its forward-thinking initiative. Soares says that the plan may ‘not have much detail yet’ but it should still be reviewed by residents ‘as a strategic document’. He says that it ‘introduces good principles’ when it comes to shaping the city’s next 20 years of development. Soares, though, also admits that ‘the challenges are huge’ and ‘therefore there is a need to work harder’ in the plan’s detailing to ensure ‘each of these challenges is addressed in an objective way in order to turn them into opportunities and future results’ which would ‘effectively achieve the master plan’s goal’. “The goal is to improve the quality of life in Macao,” he says, “and that can only be achieved by improving the quality of housing.”

Soares and Wong also highlight the creation of industrial zones – which will make up two per cent of all the land use in the city – as ‘another good principle’ in the master plan. In the plan, the government proposes to transfer the various industrial buildings dispersed across the city to a proposed four zones – the Zhuhai-Macao Cross-Border Industrial Zone in Ilha Verde, the northern section of Pac On in Taipa, Coloane’s Concórdia Industrial Park and Ka Ho in Coloane. “This idea of concentrating industrial buildings in four specific locations,” says Soares, “and in trying to reduce the potential conflict between housing and industry, is good. Also, in areas where there is industry in the residential context, the master plan includes the conversion of industrial buildings into residential buildings. We still have to see how this will be done. But it is a good principle to avoid industry in residential areas. It makes sense.”

Going public

The housing topic is undoubtedly one of the main issues in the master plan. But perhaps more complicated is the issue of public infrastructure, which will account for 23 per cent of Macao’s total land area over the next 20 years. Public infrastructure covers the facilities, structures, equipment, institutions and services that are essential to the economy and quality of life in a city, such as bridges, roads, water supplies, electric grids, schools, hospitals, courts, parks and beaches. This is why, by 2040, the plan estimates there will be even more land used for public infrastructure than housing.

Natural disaster prevention falls under the category of public infrastructure. It’s one of the priorities of the plan and proposed schemes to protect the city in the event of a disaster like a typhoon include revitalising the Inner Harbour area, with some of the docks and piers to be transformed into commercial areas in the future. There are also plans for a natural disaster prevention system to be established in the SAR over the coming years to prevent flooding in the city’s low-lying areas.

Other public infrastructure proposals in the master plan include greater investments in the city’s public transport network in order to integrate pedestrian mobility, as well as improvements to both the Light Rapid Transit (LRT) and bus systems. The plan also notes that Macao’s pedestrian system and its use of ‘green transport’ will be promoted in the future to encourage a reduction in the use of private transport. Alfred Seng Fat Wong praises a project that’s noted in the plan to introduce more sustainable transport over the coming years such as cycling and walking. “The plan is good,” he says, “as it tries to use some human-based transport, like cycling and walking, as well as the LRT, to reduce the amount of vehicles on the roads.” Wong adds that the plan ‘needs more detail on how it intends to attract people to use a combination of these sustainable transport methods’.

The government aims to improve links between Macao and the GBA, thus allowing traffic movement between the cities within one hour, as part of Macao’s regional integration. The plan proposes to reinforce the city’s transport system and ensure a permanent connection network at the main border crossing points, such as the ‘Gongbei’ Border Gate, reclamation land Zone A, the former Cotai checkpoint and the Taipa Ferry Terminal. It outlines the creation of ‘transport hubs’ or interchanges that link urban, sea and air transportation to allow faster movement from Macao to the surrounding region and also to international destinations.

In order to achieve those goals, all sorts of transport schemes are noted in the master plan, many of which are already well underway. The fourth bridge project between Taipa and the newly reclaimed Zone A is in the document, as is the new LRT East Line which will connect the Pac On area to the Border Gate while passing through the HZMB and all of Zone A. In the plan, the government also aims to increase transport links between the city’s international airport – which will itself undergo much expansion – and maritime transport via the Taipa Maritime Terminal, LRT system and HZMB port.

Wong says that Macao’s transport infrastructure is ‘key for its future development’. The professor underlines the importance of the city’s ‘cross-boundary transportation networks and facilities’ alongside the introduction of innovative technologies when it comes to facilitating traffic between Macao and the Mainland. “Transportation development is very important if we want to attract people to and from the Greater Bay Area to Macao,” he says, adding that the expansion of the city’s LRT system over the coming years ‘is crucial’ to that aim. Wong also praises the fact that Macao will be linked, in the future, to the high-speed rail network in China following the construction of an underwater tunnel to the border post on Hengqin Island as part of the development of the LRT. “The Macao government has given priority to the extension of the LRT system,” he says, “but I also hope it will consider extending the LRT lines to Iao Hon and the Inner Harbour once these neighbourhoods are revitalised.”

Going green

The environment is also a top priority in the master plan. About eight per cent of 2040’s 36.8-square-kilometre total land area will be allocated as green areas and public leisure spaces while a massive 18 per cent of the land area will be used for ecological conservation purposes. Considering that the local population is expected to reach 808,000 people, the government estimates that there will be at least 3.6 square metres of green space and public leisure areas per capita by 2040. Add the ecological conservation areas to that calculation and these green zones increase to 12 square metres per person.

Where will the bulk of these green zones go, though? According to the plan, the green and public leisure spaces are expected to increase in the northern and eastern areas of Macao’s peninsula, as well as in north Taipa and around the Outer Harbour. The plan also reveals that a 41-hectare reclamation area will be created between Areia Preta and the newly reclaimed Zone A. Plans for developments at the Outer Harbour intend to take advantage of Macao’s extensive coastline in order to provide the public with leisure areas. As a result, a continuous green space will be created in the extreme south of Macao, with highlights being a 4.8-hectare coastal garden to the south of Nam Van Lake and a 6.2-hectare coastal garden to the south of a new commercial area also in the vicinity. The Nam Van and Sai Van lakes will also interconnect in order to create a new, much larger leisure area.

North Taipa is destined for housing and ecological conservation purposes, combining residential neighbourhoods with the natural landscape. The plan also aims to establish a new commercial area in north Taipa, with a view to promoting a balance between professional occupation and housing, as well as the transformation of the coastal shoreline into a leisure area. Therefore, there will be cycle paths installed in these areas which will form an integral part of the main Taipa cycle path, creating a green and low-carbon community neighbourhood here. For the whole of Macao, the plan encourages the incorporation of ecological principles of low-carbon emissions and recycling in the new development zones.

Coast to coast

Developing Macao’s coastal areas in order to maximise the use of their green areas while also protecting the local ecosystem is one of the main goals set out in the master plan. Professor and biologist David Gonçalves, who is also the dean of the Institute of Science and Environment at the University of Saint Joseph, supports the government’s drive to create this balance. He identifies some of the main challenges faced by Macao in terms of coastal areas protection and development, saying that one of the SAR’s priorities is to ‘develop systems for effective coastal protection from extreme events such as flooding from storm surge – so frequent in Macao, in particular during typhoons’. He believes that the government’s emphasis on developing Macao’s coastal areas will go some way to developing such protection systems. The plan introduces measures to help solve the severe flooding in low-lying areas caused by disasters like typhoons and rainstorms by proposing the construction of tidal dams, water reservoirs and pumping stations. These measures could prevent flooding, drain areas and also store water. Gonçalves adds that these measures could also include natural solutions, such as mangrove planting.

Macao’s coastline is 76.7 kilometres in length and the master plan proposes to increase the amount of public leisure areas that lie along it. Gonçalves applauds this move and says there’s a need ‘to turn the city to the water’ – meaning to encourage residents to spend more leisure time next to the sea – ‘by developing leisure areas for the population near the coastline’. He also says, though, that the city must ‘protect natural coastal ecosystems and vulnerable species that inhabit the coastal waters and land, such as birds and marine mammals’. He believes that ‘the restoration of once-abundant coastal ecosystems, such as mangroves’ could serve all these purposes. “Mangrove forests are effective coastal barriers against flooding,” he says. “They are hotspots of biodiversity and they store carbon, thus contributing to the mitigation of global warming. They promote cleaner air and water and are prime areas for the population to enjoy a close contact with nature. So the priority should be to identify key coastal areas for the protection and restoration of natural ecosystems, both above and underwater.”

Environmentalist Joe Chan also applauds the master plan for the many ways it deals with Macao’s green future on land. But he notes that ‘there are sections mentioning how to boost the economic function of the ocean’ but ‘we can’t see the long-term perspective of marine ecosystem conservation or how to optimise the natural habitat for marine creatures’. He adds: “In some ways, it causes us to worry about the sustainability of ocean conservation [in Macao] in the future.”

Chan does commend the overall plan, though. “Generally speaking,” he says, “the master plan for the next 20 years of urban planning is an initial but essential step in building a sustainable city. I appreciate the government’s point of view when it comes to developing green zones for residents and tourists. And there are some great takeaways, such as Coloane, which, according to the plan, is not going to be completely urbanised in the future. I have worried about that for so long. Also, the way that recycling is treated in the plan, with specific areas for sorting and transporting the recycled materials, is to be praised. Recycling is an urgent problem in Macao and the government is dealing with it urgently. It’s now time to look forward to the next part over the coming months – many more details of specific projects.”

Overall, the master plan has been well received in Macao. Soares calls it an ‘important achievement’ and ‘good starting point’ while also noting that it ‘lacks detail’ and ‘leaves room for improvement’. He also reinforces that it’s just the start of all of these new projects on the horizon and the most important action right now is that the government listens to the public’s comments. “It’s so important that Macao’s citizens took part in the public consultation,” he says. “And now it’s equally important that their comments are understood by the government and the projects, when carried out, reflect the public’s opinion.”

“The main thing we have to say about this master plan,” continues Soares, “is that the government did very well in the sense of having a master plan. The Chief Executive made a commitment before the consultation document was published that the master plan is to be implemented. This is good news. It means that Macao’s urban development in the future will be co-ordinated by a plan.”

So, overall, the government’s master plan has been welcomed in Macao and many people are awaiting the results of the public consultation and then how the projects within the pages of the plan will play out over the next 20 years. One thing is for sure, though: Macao is going to get bigger in terms of size and population. It’s expected that, as a result of this plan, it will also get better, whether that means in terms of housing projects, environmental schemes, transport initiatives or just the beauty of everyday life in this unique Asian city.

Lining up

The Light Rapid Transit (LRT) system in Macao – which only started life just under a year ago with the opening of its Taipa Line on 10 December – gets a good airing in the master plan. One interesting detail concerns the construction of the LRT’s East Line, which will be about 7.65 kilometres in length and will encompass six stations and rails, all to be built underground – although a date for the works to begin is yet to be released.

According to the Macao Light Rapid Transit Corporation, the north part of the East Line is set to run from the neighbouring area of the Border Gate, passing through the coastline in front of the Avenida Norte do Hipódromo and the Avenida da Ponte da Amizade to the New Urban Zone A. Extending south along the central greenway of Zone A, the line then crosses the sea and connects with the New Urban Zone E at Taipa. A station here will connect to the existing Taipa Ferry Terminal Station on the Taipa Line. Once the line is completed, the trip between the Border Gate and the Taipa Ferry Terminal is expected to take just 15 minutes, thus reducing the travelling time between Macao’s peninsula and Taipa. The LRT East Line will be built in the form of an underwater tunnel so it’ll be possible to keep it functioning during bad weather. The government estimates that the total number of passengers transported daily by the line may reach up to 80,000 in the future.

Turn up for the books

Macao Central Library project in Tap Seac Square

Proposals for Macao‘s Central Library are not detailed in the master plan but this exciting development is nevertheless worth mentioning as it will affect where local residents get their books out from over the coming years.

The government’s Cultural Affairs Bureau (IC) has chosen a new location for the Macao Central Library. Under previous plans, a new Central Library was going to open at the Old Court House site in Praia Grande but these plans have now been abandoned and it looks like it could now open on the plot of the former Hotel Estoril in Tap Seac Square. The IC has said that four architectural teams from across Europe have been invited to submit proposals of conceptual design and that the new plot ‘may attain a gross construction area of more than 10,000 square metres, becoming the largest library in Macao’. The IC has also said that it ‘initially considered to adjust the functions‘ of the existing library which ‘would mainly store the collection of information about Macao and historical documents, playing its role as a complement to the new Central Library in the future‘.

The Central Library was born on 28 September 1895 in St Augustine’s Church and was regularly moved across the city over the following years before finding a home in the Leal Senado Building in 1929. In 1983, it relocated to its current site next to Tap Seac Square – a 1,371 square metre site housing more than 92,000 volumes and providing seating for 271 people – and in 2007, the government announced that a new library would be built. Details of the new plot may mean this project is about to finally open a new chapter.

And there’s more

Here are five tidbits from the pages of the master plan. Go online to find out more…

- The master plan proposes to gradually convert the various industrial buildings along Avenida de Venceslau de Morais into office buildings, accommodation and commercial sites. The aim is to reduce the adverse impact of industrial activities on residents living in the area so as to increase their quality of life.

- The government intends to reuse the old Pac On industrial area and incentivise the swap from industrial activity to high technology, making good use of new plans to transform the area. The area serves as a major transport hub in Macao. Following the strategic opportunity brought by the expansion of Macau International Airport and the Taipa Ferry Terminal of Passengers, Pac On is expected to concentrate the main transport facilities and public infrastructures. The land here is intended for public infrastructure and ecological conservation areas.

- According to the master plan, the land plots reclaimed by the authorities near Nam Van Lake will be used to build government and administration buildings.

- Large sports areas are planned for the former canidrome area that used to see greyhound racing in Macao, as well as for reclaimed land Zone A. Also, a new ‘cultural installation’ will be developed on the south side of Zone A and in Lai Chi Vun village.

- The core of tourism and entertainment industries will continue in their current locations – the Cotai and ZAPE areas, as well as in the Inner Harbour, central Taipa and Coloane. Land use in tourist and entertainment areas will become incompatible with industrial purposes. The plan also suggests the creation of a ‘Historic Tourism Belt in the Coastal Zone’ of the Macao Peninsula.