Over 100 documents of the Chapas Sínicas offer a window into many aspects of Qing‐era Macao.

A pioneering Jesuit Chinese priest meticulously documenting the spending of his church in eastern China. A famous voyager, known as China’s Marco Polo, trying to recover a loan from his Portuguese debtor. A Robin Hood‐style pirate in the South China Sea surrendering to the Qing government.

These colourful episodes and everyday realities of life in China under the Manchus come alive in over 100 historical records from the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) being exhibited in Macao this year. The selected pieces come from the collection of Chapas Sínicas (Chinese Sheets), a trove of 3,600 documents related to Macao, including more than 1,500 items of correspondence exchanged between Chinese and Portuguese officials, dating from 1693 to 1886.

On 30 October 2017, UNESCO inscribed the records on the Memory of the World

Register, an international initiative dedicated to protecting the documentary heritage of humanity. The Archives of Macao and the National Archive of Torre do Tombo of Portugal jointly nominated them for this honour.

“The UNESCO recognition is of great significance – it underscores Macao’s historical role in EastWest exchange,” said Zhang Wenqin, professor of History of Sino‐Foreign Relations at Sun Yat‐sen University. Zhang has done extensive research and written many books about this invaluable collection of historical documents.

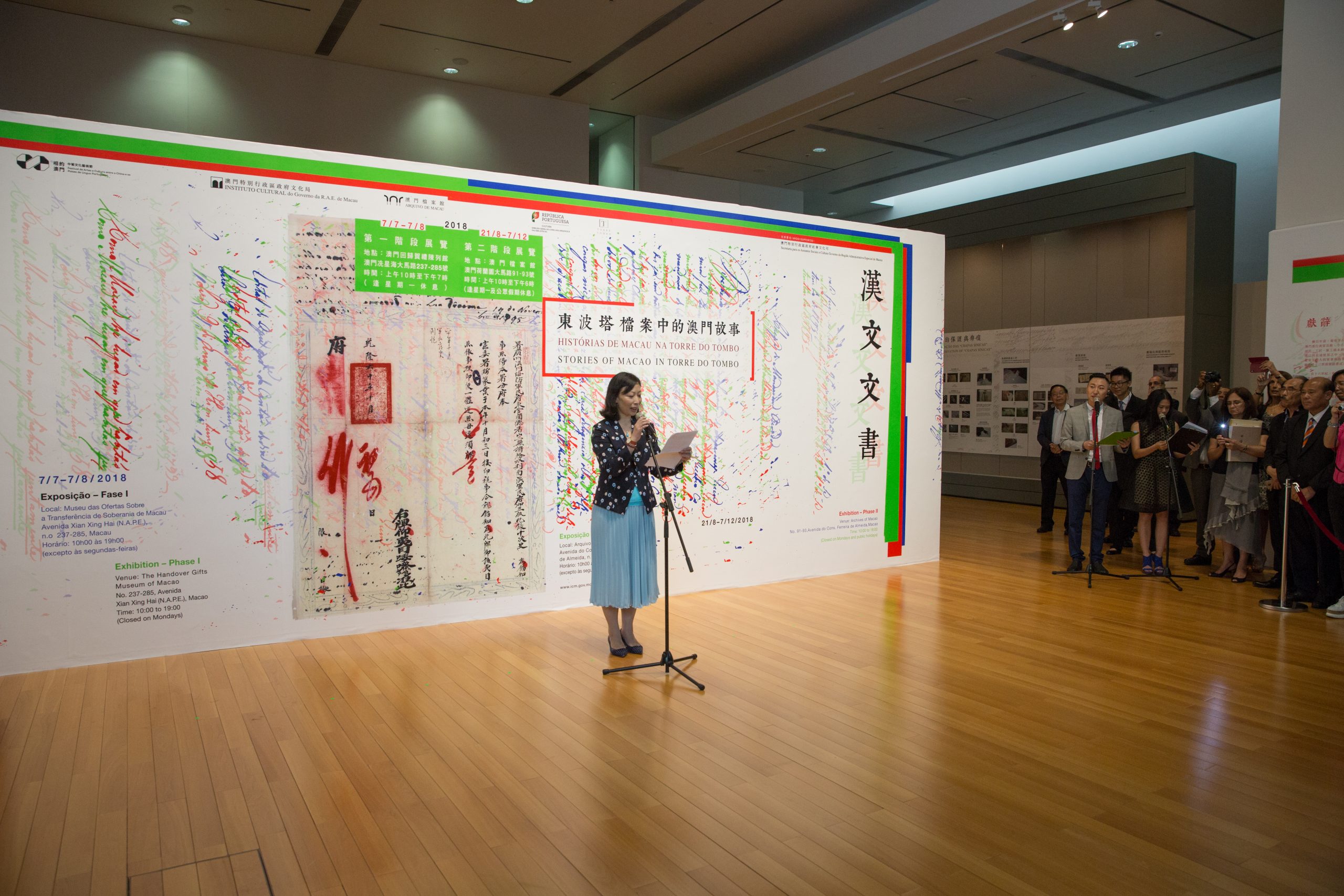

The public can examine these precious documents up close at Chapas Sínicas – Stories of Macao in Torre do Tombo, which ran 6 July to 7 August at the Handover Gifts Museum. Now the exhibition has moved to the Archives of Macao, where it will remain on display from 21 August to 7 December.

The two‐phase exhibition is part of the inaugural “Encounter in Macao – Arts and Cultural Festival between China and Portuguese‐ speaking Countries,” a series of themed events in July. The Cultural Affairs Bureau (IC), which organised the festival, lauded the Chapas Sínicas collection as “[helping] to construct a vivid picture of Macao during the Qing dynasty.”

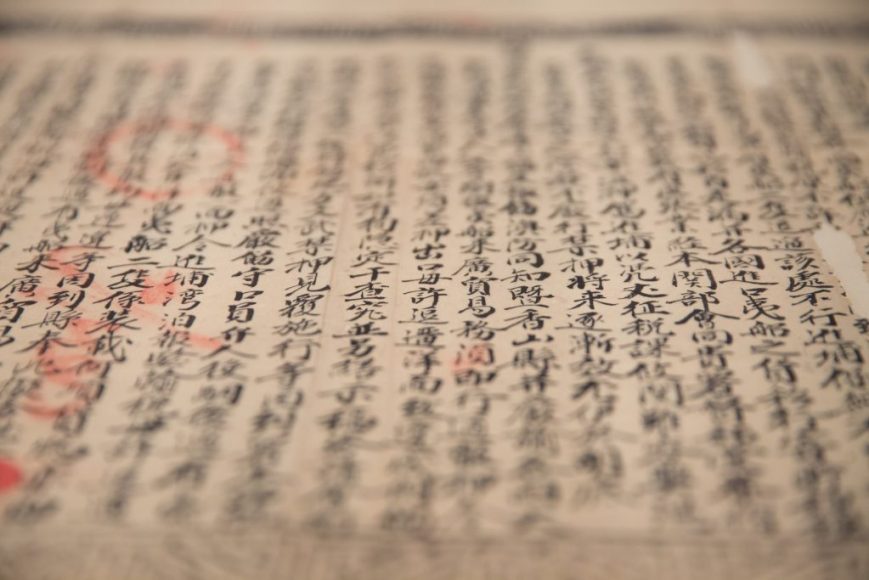

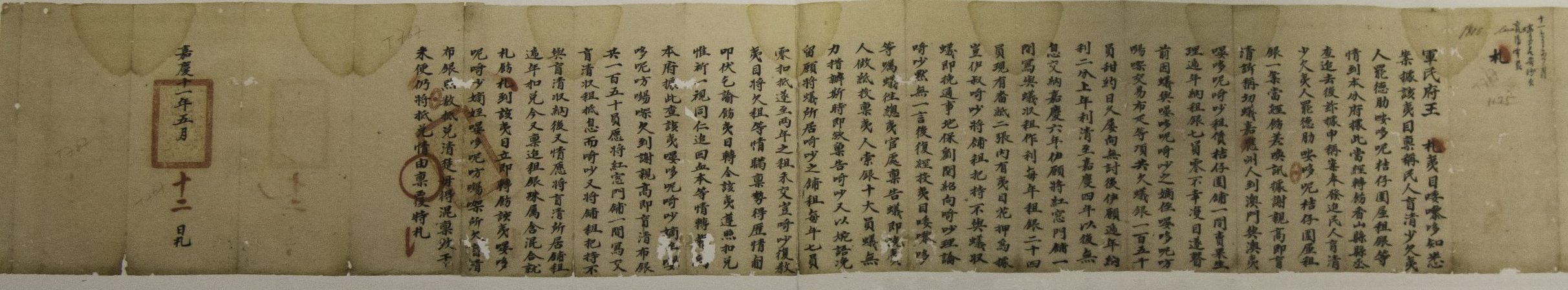

This most precious record of nearly 200 years of Macao’s history has been preserved in the Torredo Tombo in Lisbon for more than a century. The documents, many written in traditional Chinese ink on bamboo paper, describe the conditions of people’s lives, society, urban development, and trade and commerce during the period.

Reading through the various documents, one can sense the significance of Macao to the world at the time. Macao was connected through its sea trade to Britain, France, Russia, the United States, and many other countries. According to Mok Ian Ian, president of the IC, the collection represents part of an “epic memory of the world that spans ancient and modern times, and links China and the West.”

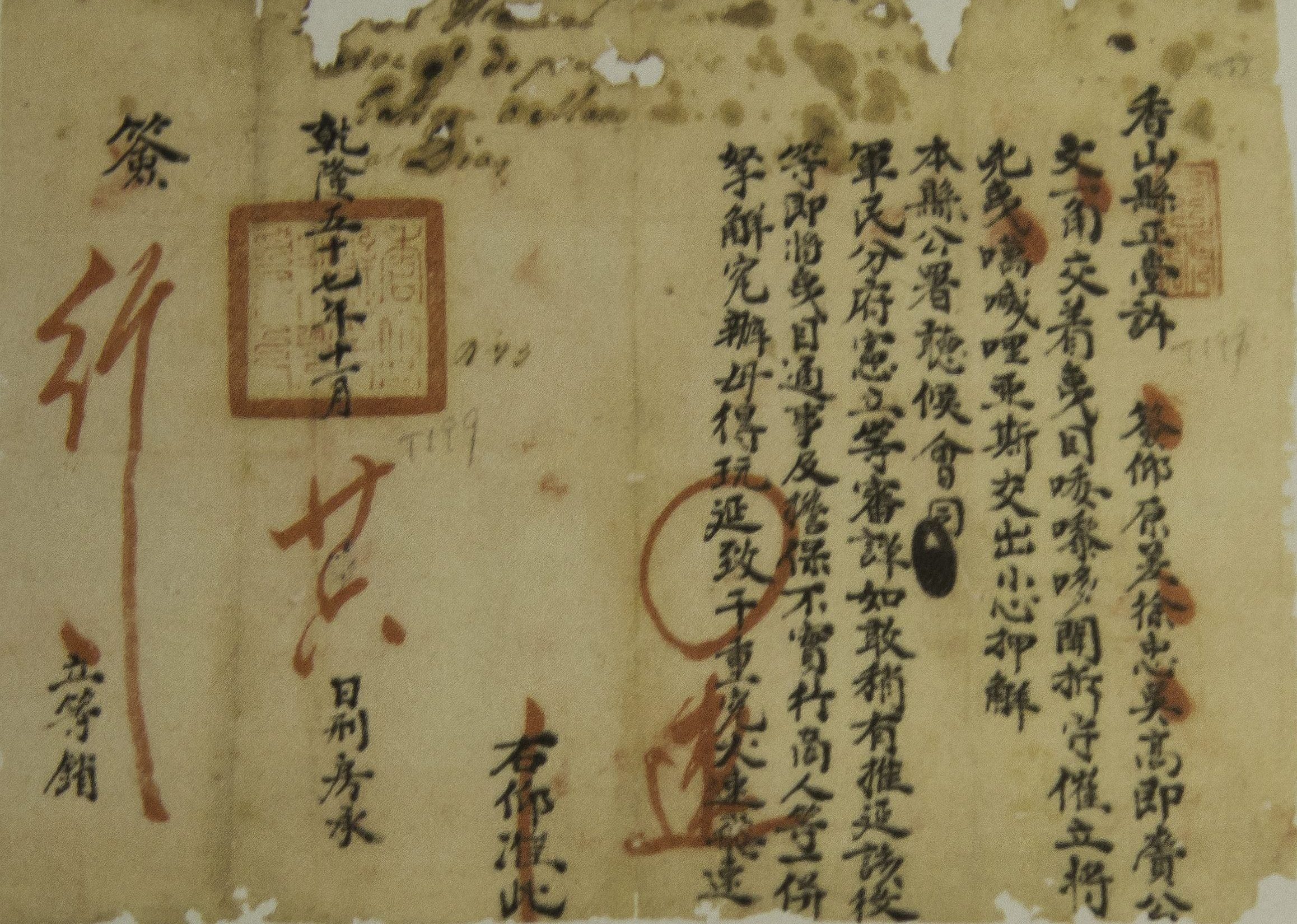

Throughout the centuries, these precious documents were kept by the Senate (Senado) of Macao. Many of the documents are letters sent between the procurators of the Senate, sub‐ ‐prefects of Macao, magistrates of Xiangshan, and other Chinese officials. Xiangshan, encompassing today’s Zhongshan and Zhuhai, was the county adjacent to Macao in imperial times.

From obscurity to publication

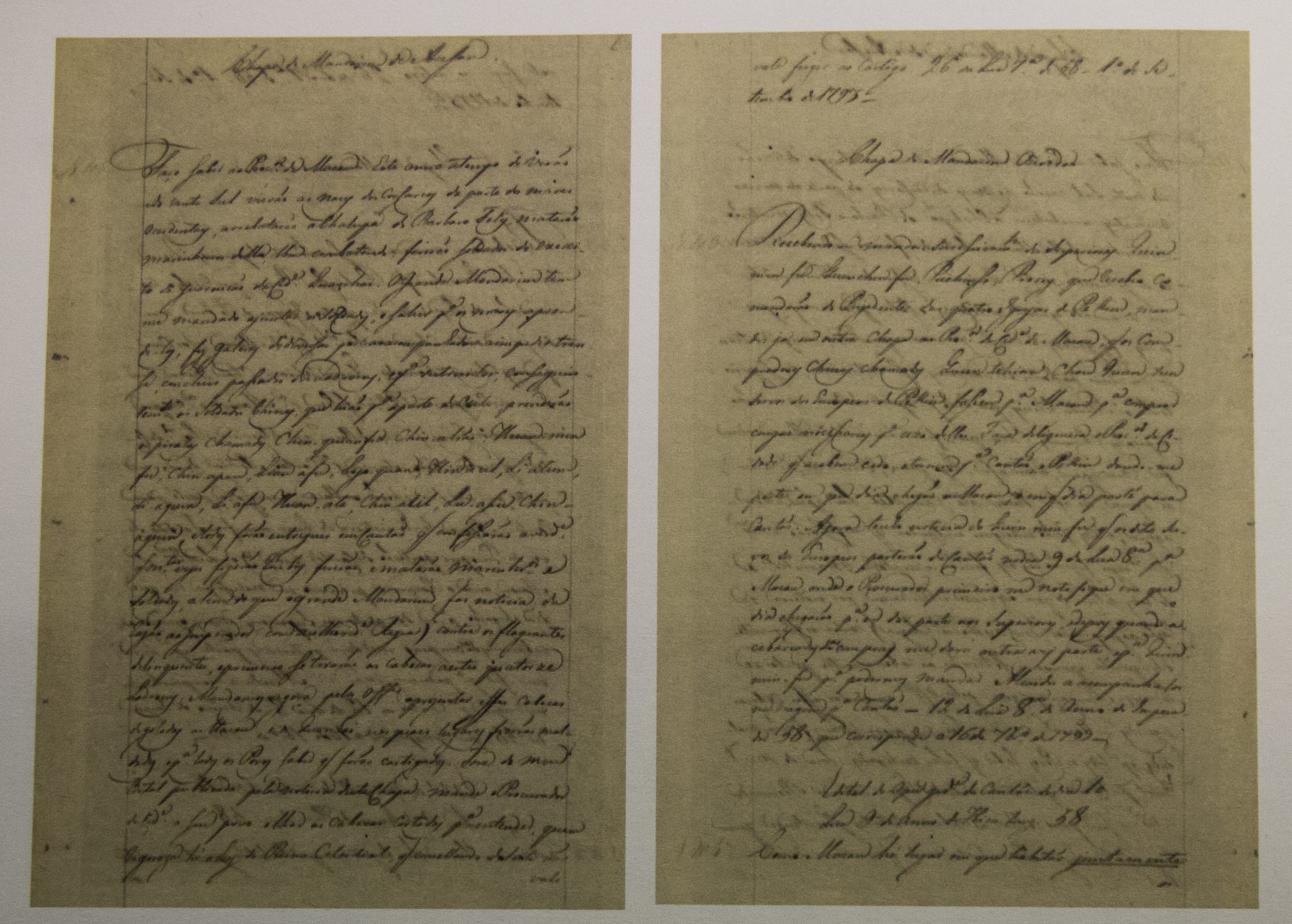

The records were later brought to Portugal and, by the end of the 19th century, were transferred to the National Archive of Torre do Tombo. For over half a century, the documents sat undisturbed in their boxes. Their Portuguese custodians had no linguistic expertise to decipher the mystery of these voluminous scrolls, but sensed their value and kept them safe in the Archivist’s room.

Even during the worst of the World Wars, the archives remained untouched by the destruction that swept across Europe as Portugal was neither invaded nor occupied. In the summer of 1952, Fang Hao, a Jesuit priest and professor of history at Taiwan University, visited the Torre do Tombo. Well known for his expertise in Sino‐ ‐Western transportation, Fang realised at once the importance of the Chapas Sínicas despite a lack of organisation or classification. His findings would attract the interest of Chinese scholars around the world.

In an article he later wrote, Fang said of his time in Lisbon: “I saw JM da Silva Marques, the director of the Archive. I cannot describe how warm was his welcome to me. He had worked there for 30 years and knew that there had been no one who had been able to make use of this material. He begged me to make a record.”

On 3 July, Fang started work,at a speed of one article every three minutes, recording the year, month and date, the author and recipient, the content and the most important details. Many documents had been damaged by insects and were difficult to read, and yet, he managed to increase his speed to one article every two minutes. But the priest had other duties; Fang left Lisbon on 14 July, less than two weeks after beginning the project. Even at his rapid pace,there was still much work left to do. He proposed to Director da Silva that he hire two Chinese students in Spain to complete the work, but the Archive had no budget for this.

Fortunately, numerous Chinese and Portuguese scholars followed Fang to conduct research on the collection, including: Pu Hsin‐ ‐Hsien, Isaú Santos, Lau Fong, Tang Si Peng, Li Dechao, Zhang Wenqin, Jin Guoping, Wu Zhiliang, and Antonio Vasconcelos de Saldanha. Each contributed to the cataloguing, transcription, arrangement, and study of the collection.

A full survey of the documents was not conducted for another 30 years, when former director of the Archives of Macao, Isaú Santos, went to Lisbon in the late 1980s. He took microfilms of the documents, catalogued them, and began the long and difficult task of preparing them for publication.

In 1995, using a version on microfilm, the IC published a catalogue of the Chapas Sínicas

in Chinese and Portuguese. The Macao Foundation published the Chinese and Portuguese records in 1999 and 2000 respectively.

The Chinese version was released in two volumes of 1,200 pages, by Zhang and Lau Fong, the current director of Archives of Macao. The Portuguese version, by Jin Guoping and Wu Zhiliang, was much longer at 4,000 pages in eight volumes.

A priest, a voyager, and a pirate

Although only a fraction of the Chapas Sínicas, the more than 100 documents selected for the exhibition offer visitors a window into so many aspects of Qing‐era Macao.

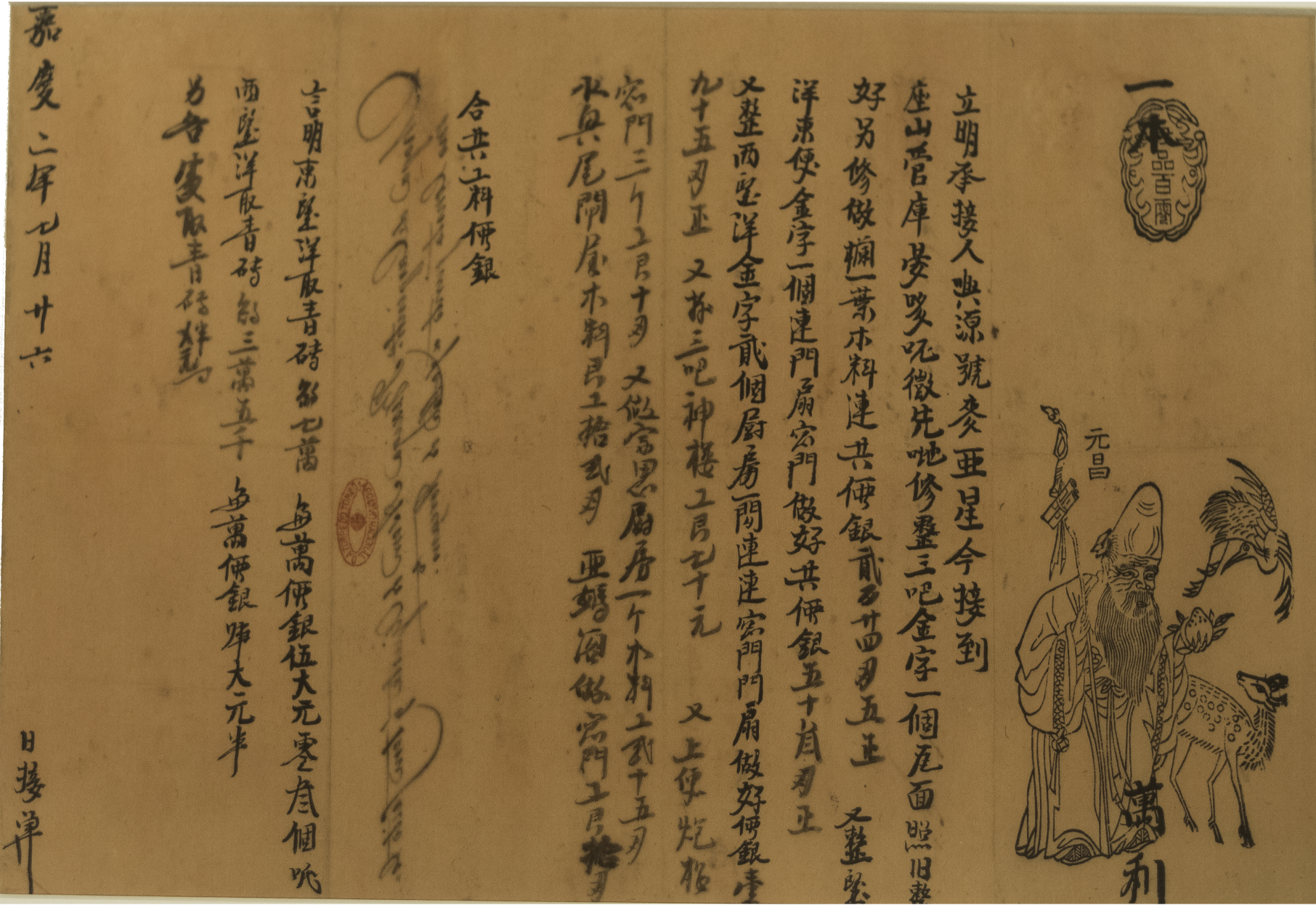

There’s an arrest warrant, issued in 1793 by the magistrate of Xiangshan, ordering a foreigner who killed a Chinese to be handed over to the Chinese authorities for trial. One letter, sent in 1804 by the commissioner of Customs in Macao, informs the procurator of Macao that foreign vessels leaving the city for Whampoa must have their licence with them. A contract reveals the Chinese contractor who did plaster and repair work on St Paul’s Church in 1797.

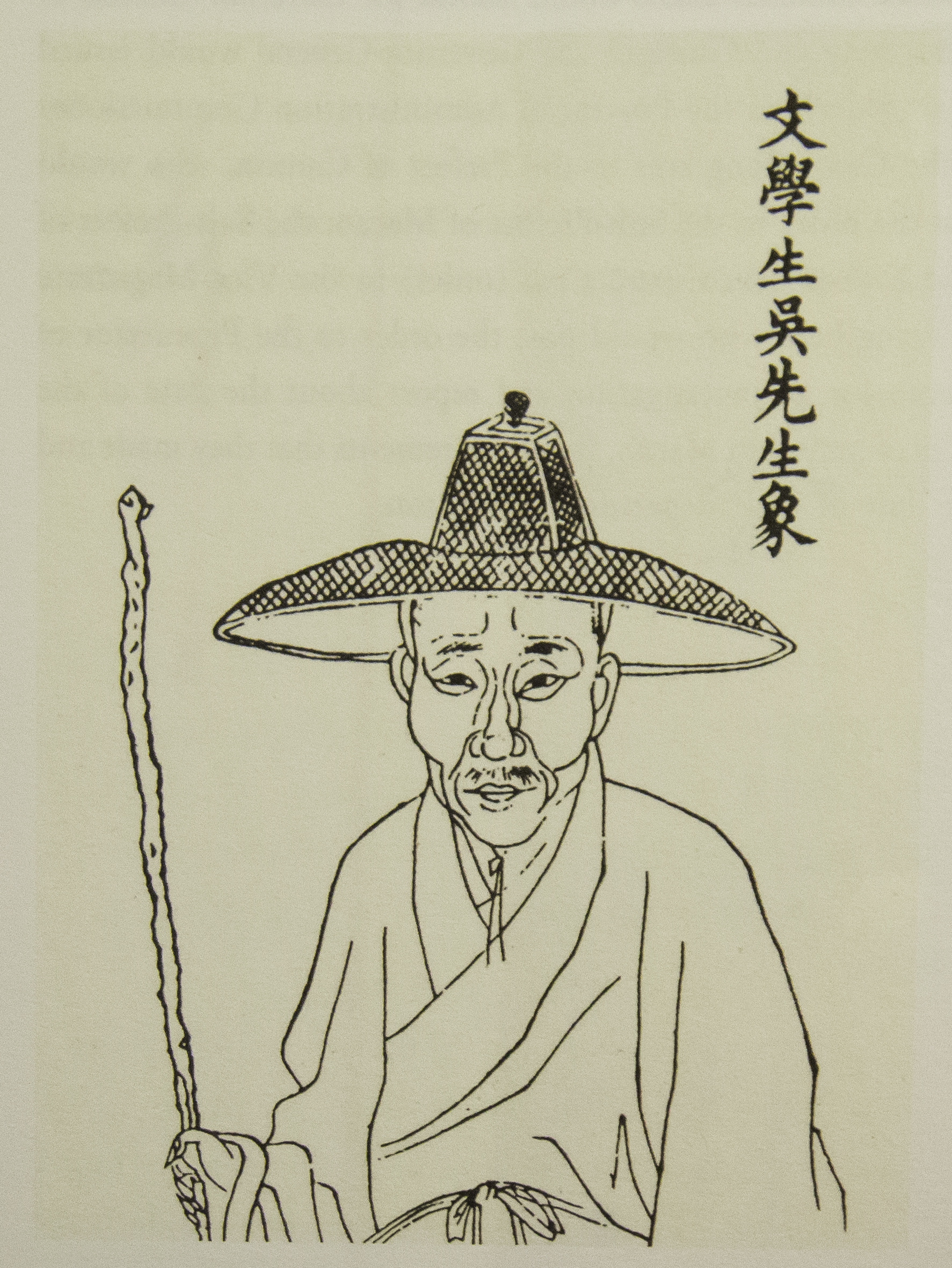

From this broad spectrum of stories, Zhang Wenqin highlighted the lives of three particularly interesting personalities. One is Wu Yu‐shan, also known as Wu Li, a gifted landscape painter and calligrapher, as well as one of the first ordained Chinese Jesuit priests. He studied at St Paul’s College in Macao from 1680 to 1683, then in 1688, he was consecrated a parish priest in Nanjing. Wu continued his missionary activities in Shanghai and Jiading until his death in 1718.

The Chapas Sínicas contain an account book kept by Wu for a church in Jiading, with entries for transactions related to food, supplies, tailoring, book stands, and repair works. “One most interesting detail,” Zhang noted, “was the record of Wu paying for Chinese medicine on two occasions when he was sick.”

The book runs to 231 pages; Wu was then serving as the parish priest of Jiading, the centre for the spread of Catholicism in the Jiangnan region of China. The second figure of note, Xie Qinggao, brings a taste of adventure – and the mundane difficulties faced by many Chinese of the day. The Chapas Sínicas contain five official records of a tenancy dispute between Xie and two Portuguese during 1806 and 1808.

Xie had an extraordinary life. At the age of 18, he became a crew member on a Portuguese trading vessel after being rescued when his own vessel sank in the open sea. His voyages brought him to Portugal, Britain and beyond, enabling him to acquire foreign languages and a good knowledge of the geography, customs, and traditions of different countries.

Upon losing his eyesight, however, he returned to China and settled in Macao, where he made a living as a merchant and interpreter.

As the Chapas Sínicas records reveal, in 1793, Xie lent 150 yuan to a Portuguese named Antonio Fonseca; he failed to repay it despite many demands. In 1801, Fonseca signed a promise saying that Xie should collect the rent of his house as interest on the loan he had not repaid. The promise was broken, forcing Xie to write several times to the vice magistrate and magistrate of Xiangshan and the sub‐prefect of Macao. His efforts failed.

During the Qing dynasty, there were many cases of Portuguese civilians and officials trying to evict Chinese tenants and demolish their homes and shops in order to redevelop the land. In these cases, the Chinese officials cited the relevant regulations and said that existing tenancies should remain in force: eviction and rent increases were prohibited.

If the tenants did not pay rent, the Chinese officials would work to recover the arrears and the Portuguese could not send their slaves to evict the tenants. The public today can have a glimpse of such unfairness through the complaints detailed in these historic documents.

When Cheung formally surrendered on 20 April 1810, he handed over 280 ships, 2,000 guns, and more than 25,000 men. For their part, the Portuguese asked for no reward, which greatly impressed the Qing officials.

The third takes visitors to the high seas: Cheung Po Tsai, a pirate commander who later became a colonel in the Qing navy. Born in Jiangmen in 1783, he was abducted at 15 by a pirate. Pressed into piracy himself, his natural skill soon elevated him to a leadership position. But between September 1809 and January 1810, he suffered a series of defeats at the hands of the Portuguese navy in the Zhujiang River Estuary.

When Cheung formally surrendered on 20 April 1810, he handed over 280 ships, 2,000 guns, and more than 25,000 men. For their part, the Portuguese asked for no reward, which greatly impressed the Qing officials.

The Chapas Sínicas contain a number of documents relating to Cheung’s short but dramatic life. One is an official letter from the Qing government to the procurator of Macao, announcing the arrest and decapitation of the pirates, and ordering the public display of their heads to prove the rigour of the law of the Qing Emperor. Another is a letter from the magistrate of Xiangshan to the chief justice of Macao on Cheung’s capitulation.

After his surrender, Cheung settled in Macao and was appointed a captain in the Qing imperial navy, responsible for eradicating piracy. He reached the position of deputy general three years before his death in 1822; he was 39 years old. A street in Macao bore his name until it was destroyed during the Second Sino‐Japanese War.

Fight to protect the record

Preserving thousands of delicate documents is no mean feat and often involves mending the ravages of time. Dr Silvestre de Almeida Lacerda, general director of the General Directorate for Books, Archives and Libraries of Portugal, described the painstaking efforts taken to restore the centuries‐old scrolls to legible form to a lecture audience in Macao on 8 July.

“We have ten staff devoted exclusively to the project, with the help of Archives of Macao as well. We compare information obtained from both the Portuguese and Chinese translations,” he explained. “We believe some of the documents were first translated from Chinese into Latin before Portuguese, probably because the Church was involved in the translation in those days and Latin was a common language among Westerners.”

By 2015, Torre do Tombo had assessed 1,501 documents of the Chapas Sínicas and listed 1,606 preservation tasks for the individual records.

There are four classifications of the state of the documents: no damage, limited damage, damage not exceeding 50 per cent, and severe damage of more than 50 per cent. The damage was caused by rot and infestation by insects and moths, relatively common issues which can arise from everything from environmental factors to accidentally leaving a bookmark between the pages.

We believe some of the documents were first translated from Chinese into Latin before Portuguese, probably because the Church was involved in the translation in those days and Latin was a common language among Westerners.

Silvestre de Almeida Lacerda

The restored Chapas Sínicas documents have been digitised and made available online, providing valuable resources for scholars, researchers, and other interested readers. The collection from Torre do Tombo is only part of a much larger cultural trove: experts estimate there are nearly two million historical documents worldwide that relate to the history and culture of Macao.