TEXT António Bilrero

After centuries as the hub connecting China to the Portuguese‐speaking world, Macao views language as the next frontier for exchange between the two worlds. Three institutions – University of Macau, Macao Polytechnic Institute, and the Instituto Português do Oriente – stand at the heart of this effort, providing Portuguese language training in Macao and support to the Economic & Trade Cooperation and Human Resources Portal, a valuable tool facilitating economic and trade cooperation between China and Portuguese‐speaking countries (PSC).

Speaking in separate conversations, the relevant directors from all three institutions agreed: the Portuguese language has a promising future in China and will play a crucial role in consolidating relations between the world’s second biggest economy and the eight countries (in addition to Macao) that make up the Portuguese‐speaking world. In China, interest in learning Portuguese has exploded like no other language in recent years. As the home of Portuguese in the East, Macao has a central role to play in this growing trend – even more so if Portuguese‐speaking people seek to learn Chinese, the most widely spoken language in the world.

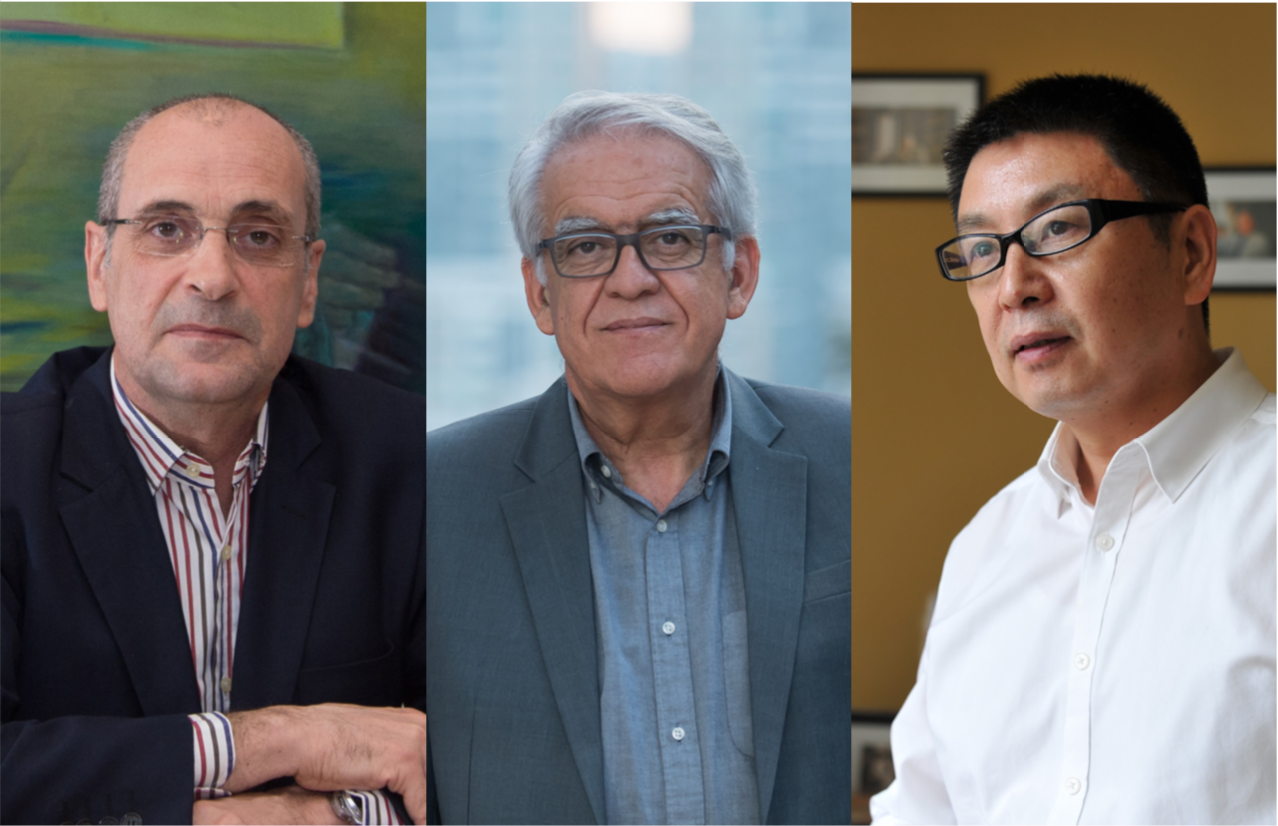

Although each framed the language’s recent growth in different terms, Professor Yao Jing Ming, head of the Portuguese Department of the University of Macau (UM); Professor Carlos Ascenso André, director of the Portuguese Language Teaching and Research Centre at Macao Polytechnic Institute (IPM); and Dr. João Laurentino Neves, director of the Instituto Português do Oriente (IPOR) share an optimistic outlook on the future of Portuguese in the Far East.

Rise of Portuguese in China

For Dr. Neves, one of the decisive vectors for strengthening and expanding Portuguese in the Far East centres on the role of local authorities is in its dissemination.

“Today more institutions are offering Portuguese, there are more conditions for learning Portuguese in Macao, and above all there’s a lot of support from the authorities for learning,” he said. “Altogether this has had a major impact on teaching the language.”

Professor André recognised in turn that the Portuguese language “still has a lot of room to grow” in China, although he did acknowledge “from a realistic standpoint” that “Portuguese will always be a minority language for teaching in China, after English, Russian or Japanese.”

“However,” he added, “I believe that Portuguese can one day reach the level of 10,000 higher education students in China [current numbers are around 4,000].” André sees public demand in higher education as a primary driver for adoption of Portuguese language programmes at the secondary school level. He noted that “there are nearly 200 university professors working in the area in China – six years ago there were less than 20.”

“Portuguese is currently studied in all provinces on the Chinese coast. Of course, there are differences. There’s no symmetry: it’s studied in universities, public and private institutions and schools. But it’s studied in the country from North to South.”

He therefore believes that “in China no language will grow so much as Portuguese.” Such growth, he added, “is quite unprecedented in the world, so suddenly, in less than ten years.”

This rapid growth in interest and institutional support lead Neves to conclude that this is a “good time” for the Portuguese language in the Far East. “The talk in favour of Portuguese teaching, of strengthening the Portuguese language in state organisations, schools and multilateral institutions, that political aspect up to the local authorities has had a major impact” on the increased interest in learning the language, he argued.

Carlos Ascenso André, director of the Portuguese Language Teaching and Research Centre at Macao Polytechnic Institute (Middle)

Yao Jing Ming, head of the Portuguese Department of the University of Macau (Right)

Photos by Cheong Kam Ka

He therefore sees no major reason to doubt that a “lot of leeway will be given to Portuguese language learning.”

“The indicators tell us that on the one hand there is demand for Portuguese as a language of communication and on the other that there is very strong demand for a language used in specific areas, namely the world of business and administration,” he explained.

“All this gives us an idea that the Portuguese language’s vitality is very strong and that it is apparently rooted in the major activity sectors of a community like Macao.”

I believe that Portuguese can one day reach the level of 10,000 higher education students in China [current numbers are around 4,000].

Carlos Ascenso André

Building bridges for cultural exchange

The political support touted by Dr. Neves, while crucial to success, is not enough on its own. Fully realising the potential of Portuguese language learning in China will require the development of relationships across borders, connecting teachers and students with the opportunities and support they need.

Professor Yao emphasised the importance of first‐hand experience for students, noting that “to learn a language well you have to be familiar with its culture.” To this end, the University of Macau signed agreements with universities from Portugal, Brazil, and other Portuguese‐speaking countries that afford its students the opportunity to study abroad. That cooperation, he said, “aims to be consolidated in the near future.”

The university hopes “to create a mechanism allowing students to obtain their licenciatura (Bachelor) degrees in Macao, and then go on to universities in Portugal and Brazil to continue their studies at master’s level,” he revealed.

For Yao, creating this educational pathway means that “the master’s degrees in Portuguese‐speaking countries will be very effective for students, and very attractive for those who want to learn Portuguese and Portuguese‐ ‐language culture.”

Professor André focuses more on teachers and building connections with mainland China in his role as director of the Portuguese Language Teaching and Research Centre at Macao Polytechnic Institute.

The recent boom in Portuguese language learning in China – now offered at 35 Chinese universities, versus barely a half‐dozen a decade ago – proved difficult to keep pace with, as André explained: “There were and are some problems in recruiting teachers and with material and inter‐institutional relations, and dialogue with the Portuguese‐language countries.

“When it all began there were only three or four universities; there was no way to produce professors who could support that growth.” Of the 200 current professors, 140 are Chinese, while the rest are mostly Portuguese along with several Brazilians.

Such a limited pool of candidates, André noted, created issues: “Those teachers are very good at speaking Portuguese, they have excellent proficiency, unparalleled generosity, huge amounts of enthusiasm… but speaking Portuguese well does not make you a good foreign language professor.”

To improve their efficacy as educators, “these young Chinese needed support. And that support means training.” Providing this type of ongoing teacher training is a central focus of IPM’s Portuguese Language Teaching and Research Centre – and its “biggest asset,” according to André. “We don’t train people to become teachers, we provide training to actual teachers.”

Centring Macao

Despite centuries of Portuguese rule before the handover in 1999, little Portuguese is spoken on the streets of Macao; less than 10 per cent of the population claim fluency in the language. Neves downplayed this, noting that the goal of the efforts to promote Portuguese language teaching is not to reproduce here “the situation of a country where Portuguese is the official language.”

“It’s unreasonable to think that way,” he argued. “What’s Yao Jing Ming, head of the Portuguese Department of the University of Macau fundamental is the Portuguese language’s presence in strategic sectors of activity of the society, economy, and administration – and yes, that’s a concern.

We would like the Portuguese language to be present for whoever wants it, so that any citizen can have access to it.” Yao countered that this emphasis on Portuguese language training – appropriate given the much larger population of Chinese speakers – should not preclude efforts to engage the rest of Macao.

“Bilingual training cannot be just for the Chinese. Our view on this matter has to be expanded. It has to evolve to bring Portuguese and Macanese into the bilingual training plan,” he said. “They also live in this bilingual environment.”

That’s why Yao believes the government should create a plan that would “include Chinese heading to Portugal and Brazil, for example, while also encouraging Portuguese and Macanese to learn Chinese in mainland China, Taiwan, or Macao.”

He considers it vital to motivate “Portuguese and Macanese to learn Chinese.”

“That is the way to effectively create more bilingual personnel, making Macao the hub for that training. In other words,” he explained, “an action line in both directions and with three actors: Chinese, Portuguese and Macanese.”

The primary focus, however, remains on the Portuguese language, and how accelerating dissemination in Macao, and China more broadly, serves long‐term political and economic goals.

“If Macao is effectively able to play the role reserved for it by the central government” – to be a platform connecting mainland China and PSC – “then it will have a more brilliant future, because many people who want to learn Portuguese will choose to do so here.” Neves concurred: “Macao should serve to anchor Portuguese language training in the Asia‐Pacific region,” he said, recalling that in the Belt and Road political initiative “there’s also an aspect associated to the Portuguese language.”

Portal supports Portuguese language training

Portal supports Portuguese language training All three institutions University of Macau, Macao Polytechnic Institute, and the Instituto Português do Oriente are developing the necessary capacity to facilitate the expansion of Portuguese language learning.

Meanwhile, the Economic & Trade Co‐operation and Human Resources Portal serves as a useful hub for connecting and promoting bilingual speakers in Macao, China and the Portuguese‐speaking countries.

Launched in 2015 by the Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China and by the Secretariat for Economy and Finance of the Macao government, the portal is coordinated by Macao Trade and Investment Promotion Institute; Forum Macao serves as the special cooperation organisation for the project.

It operates as a tool for economic and trade cooperation between China and Portuguese‐speaking countries, providing a broad range of information services. Among them, the “Bilingual Personnel Database” and “Professional Service Providers” serve as a platform for companies to gain quick access to information about bilingual professionals with different areas of expertise such as translations, public relations, legal, accounting tourism and exhibition. Information of the service providers such as education backgrounds and current residency are also provided in the databases.

Meanwhile, bilingual professionals who wish to join the database are required to fill out the application form online in three languages: Chinese, Portuguese and English. Until now, the database has accumulated nearly 1,000 registrations from service providers based in mainland China, Macao and the PSC. The platforms created by the portal make it possible for quick pairings between clients and service providers, ensuring that language is no barrier to prospective partnerships and investments.

Companies can also access information through the portal on relevant countries, updates on conventions and exhibitions, as well as information on trade legislation, public relations, banking, and public works.

The origins of the portal project date back to the 4th Ministerial Conference of Forum Macao, held in November 2013 in Macao. Speaking at the conference, Chinese Vice Premier Wang Yang announced eight new measures to strengthen Macao’s positioning as a trade platform. One of the measures called for the creation of the Economic & Trade Co‐operation and Human Resources Portal, to serve as an information‐sharing platform for bilingual professionals and business cooperation, exchanges, and interaction between China and PSC.

Confucius Institute opens in Macao

In addition to its efforts to build exchanges with institutes in Portuguese‑speaking countries, the University of Macau is set to host a local branch of the Confucius Institute. Scheduled to open in the first half of this year, the institute will be headed by Hong Gang Jin, current dean of the university’s Faculty of Arts and Humanities.

Establishing a Confucius Institute in the territory will help Macao assert its position as an international platform for promoting Chinese language teaching abroad, especially in PSC.

The institute aims to leverage the advantages offered by Macao’s location, its status as a special administrative region, and its linguistic diversity to become a platform for Chinese language teaching. Promoting student exchanges with PSC will also be one of the goals of the Macao branch.

In creating the Confucius Institute project, China drew on the experience of countries such as the UK (British Council), France (Alliance Française), Germany (Goethe‑Institut), and Spain (Instituto Cervantes), all of which seek to promote their respective languages and cultures in the world.

Established in 2004, the Confucius Institute is a non‑profit educational institution based on the principle of cooperation between the People’s Republic of China and friendly countries and partners, with a well‑defined objective: to disseminate and improve understanding of Chinese language and culture.

Confucius Institutes around the world:

- 170 branches in 21 countries in the Americas, with 110 in the United States. At more than 500 classrooms, the US hosts more branches of the institute than any other country.

- 160 in 41 European countries. The UK hosts the most at 29, followed by Germany (19), France (17), and Russia (17).

- 115 in 33 Asian countries, with 23 located in South Korea.

- 48 in 32 African countries, with 5 branches in South Africa.

- 18 in 3 countries in Oceania, with the majority (14) in Australia.

With multiple branches in both Portugal and Brazil, recent years have seen the Confucius Institute expand into a number of Portuguese‑speaking countries in Africa. In Mozambique, Zhejiang Normal University partnered with Eduardo Mondlane University in Maputo in April 2012 to establish an institute.

A partnership between Harbin Normal University and Agostinho Neto University in Luanda brought the first Confucius Institute to Angola in February 2015. It also marked the first branch sponsored by a Chinese company, state‑owned investment giant CITIC Group. In December 2015, the University of Cabo Verde in Praia joined with Guangdong University of Foreign Studies to bring the project to the small island nation.