Macao had a pivotal role in the spread of Western printing technology in the 18th and 19th centuries. We take a look at why.

It is one of the most important inventions in the modern history of man. Without the printing press, there would be no Scientific Revolution or Renaissance. Books or newspapers would not have been created easily and efficiently and then distributed around the world, sharing knowledge and scientific discoveries with anyone who could read. This invention began a cultural revolution with a global effect.

Spreading from Europe through trade routes to the East, it was the Portuguese trading post of Macao that moved this technology throughout East Asia during the 18th and 19th centuries, making the city a major contributor in bringing printing to the world. This pivotal period in the region’s history was explored in the ‘Macao’s Role in the Spread of Western Printing Technology across the East’ exhibition earlier this summer at Senado Library. Here, rare original prints of books, periodicals and newspapers in five languages gave a fascinating glimpse into the past, telling the story of great entrepreneurship in Macao, which helped revolutionise the spread of information in the East.

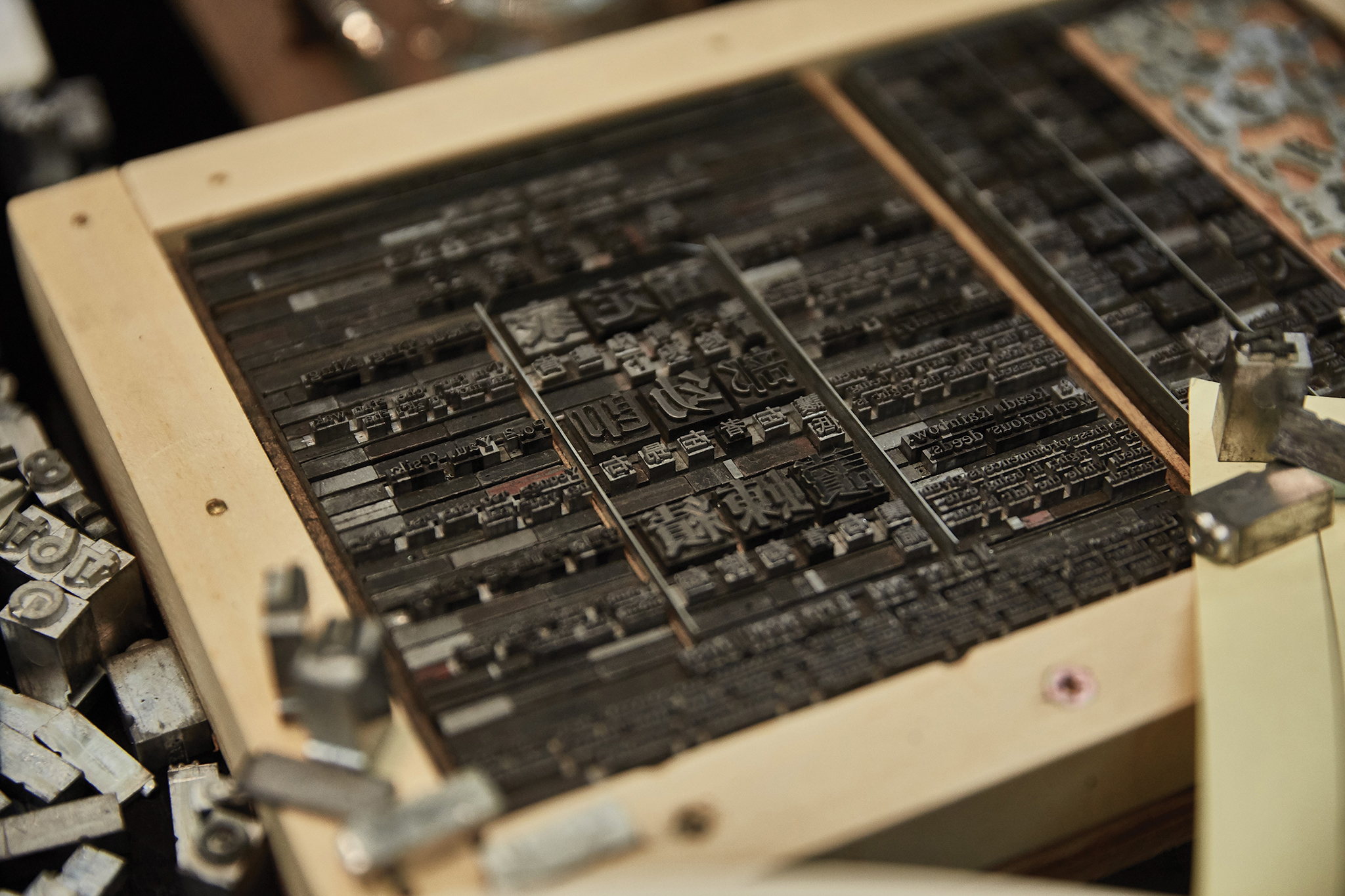

Native people from Macao worked alongside British, American and French missionaries to create leaden moveable-type Chinese characters, leading to the further spread of the technology throughout China. But, more than a thousand years prior, the first printing blocks were carved out of wood in China.

From China to Europe

The mechanical printing press was invented in 1450 by a goldsmith’s son, Johannes Gutenberg, in the German town of Mainz. He introduced the revolutionary concept of movable type and the printing press to Europe, which was revolutionary, with Gutenberg playing a pivotal role in putting the necessary elements together for the creation and proliferation of this technology.

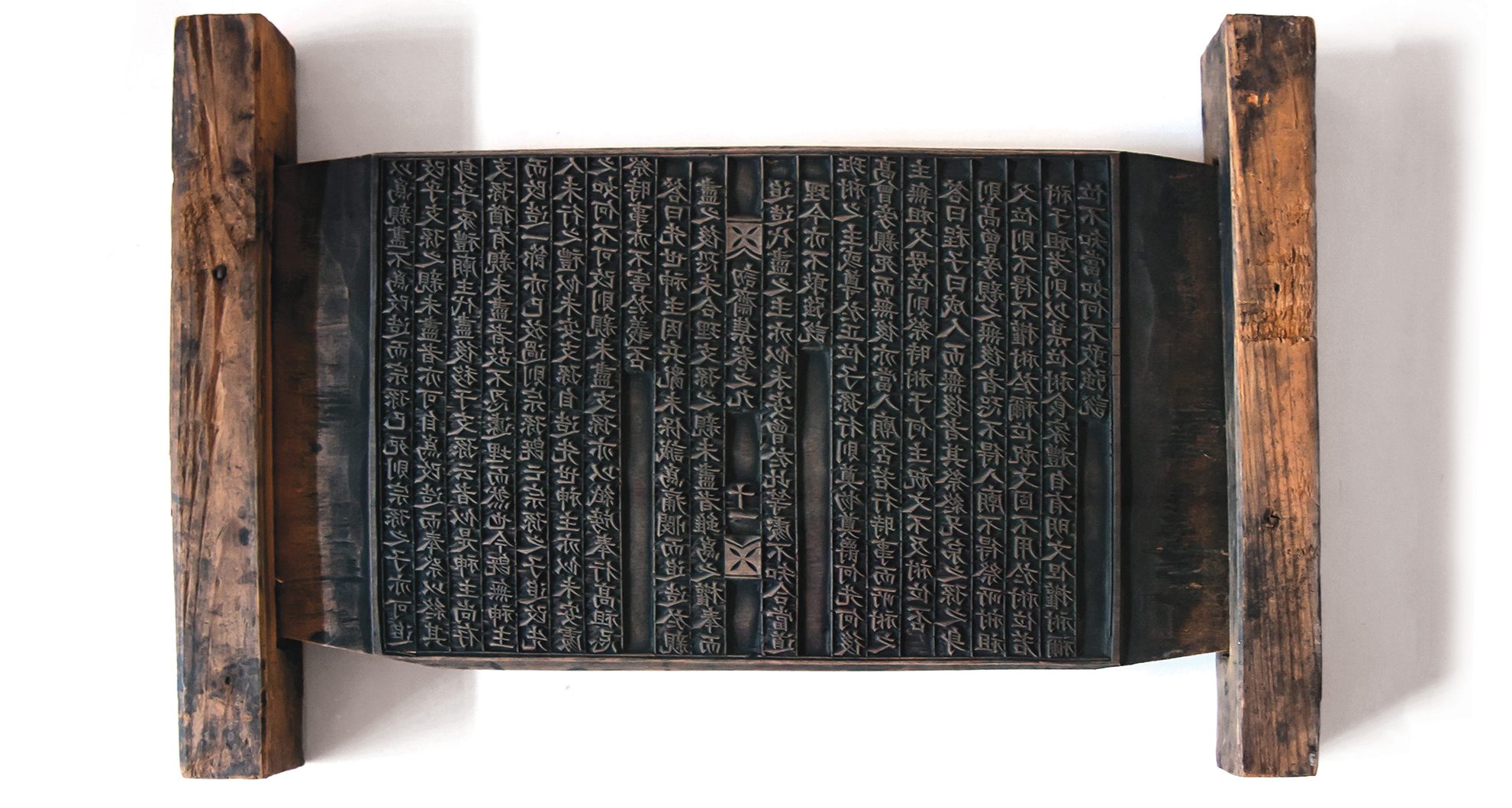

However, more than a millennia earlier, around 200AD, the foundations were being laid by Buddhist monks in China. Intricate carved wooden blocks set ink to paper using a method known as block printing. A woodblock from the period survives at the Ningxia Museum, Yinchuan, in northern China. It was discovered in 1990 in Ningxia’s Hongfo Pagoda.

During the Song Dynasty (960-1279AD), between 1041 and 1048, Chinese artisan Bi Sheng invented movable type, allowing for faster, more accurate printing using precisely cut clay blocks. The technology developed, spreading to the Korean peninsula, where it was used for centuries. Eventually, this printing technology made its way to Europe through the traders of the Silk Road.

Tom Christensen is a prolific author who served as the director of publications at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco for 16 years. The self-confessed ‘typehead’ is an expert in early printing technology. He explains that ink and block printing unquestionably travelled from China to the West. “At the time of the Goryeo Dynasty [in Korea],” he says, “the Mongol empire stretched all the way from Korea to Eastern Europe. There is plenty of evidence of lively economic and cultural exchange across this vast empire. It would be surprising if awareness of Asian cast printing did not reach Europe.”

In 15th century Europe, xylographic printing with wooden blocks was common although many manuscripts were still copied out by hand, a much slower method executed with great pride by the scribes of the time. The expense that was involved made books the preserve of the ruling classes.

Meanwhile, Gutenberg was working on a way to speed up this process. He broke down the blocks into individual characters and symbols and cast them in tin and lead. He developed a machine, adapted from a wine press, to automate the pressing of the blocks on to the paper – far more efficient than pressing individual letters by hand. Hundreds of pages could be printed at a time, saving hours of painstaking typesetting that was previously required to produce just one page.

In 2008, Alan May, the foremost expert in Gutenberg’s invention, reproduced a 15th century Gutenberg press from old drawings for a documentary starring Stephen Fry on British television. May explains: “Gutenberg’s genius was to bring together a number of separate technologies into a workable system, including devising a means of making type, constructing a press that could be used for printing, making a printable ink and using paper rather than vellum as his substrate.”

“Bringing these technologies together into a commercially workable system for making books had an astounding impact on the medieval world and did much to kickstart the Renaissance,” May adds. He also says that by 1500, there were around 1,000 printing presses in operation in Western Europe with an output of over eight million books. “This figure,” he says, “continued to grow exponentially over the next three centuries.”

This was a revolution as impactful as the rise of the internet today – and it would continue to change the way information was stored and disseminated for centuries. Yet, mechanical presses remained unknown in East Asia. Instead, printing was a laborious process of pressing the back of the paper on to an inked block by manual ‘rubbing’ with a hand tool. But how did this technology finally reach Macao and travel further into Asia?

Printing technology returns to Asia

In the latter half of the 15th century, Gutenberg-type machines were spreading all over Europe. Rapidly improving versions of the inventor’s original printing press enabled an explosion in publishing. Christensen explains: “Although European print technology was first developed in Germany, Venice was the most multicultural city in Europe at the time – and the most literate – producing printed texts not only in Latin and Italian but also in Arabic – including a Koran – Greek, Armenian and other languages. Venice was the gateway to Asia.”

Travellers, traders, settlers and missionaries all had reasons to mass-print books and ledgers. And so presses started to spread through trade routes. The first printing press in Asia arrived in Goa in 1556. Onwards through the colonies, the new printing methods gradually spread across the globe – however, printing was still extremely expensive and remained the preserve of the colonial powers.

It was a missionary party from Japan that took the printing press further into Asia. From Goa, their next stop was Macao. And thus, printing technology, in a more sophisticated form, returned to the land where it had been invented over a thousand years earlier. Yves Camus explains in his paper, ‘Macau and the Jesuits’: “A printing press was to be shipped to Japan and another to Macao in 1595, a copy of which is still exhibited in the Macao Museum. The printing press has been the source of many pastorally useful catechetical materials, translations of Eastern or Western classics and other scholarly publications.”

The replica remains in the museum to this day, one of the earliest examples of Gutenberg’s movable-type printing presses in the Far East. A representative of the museum tells the story of the original: “After its arrival in Japan, many Japanese characters were added to the heavy machine which was quick to fall into disuse. It was sold to Augustinian fathers in Manila and has since been lost.”

Spreading across the East

At the time, the Chinese Ming government and the ruling government of Macao were not keen on this newfound spread of information. Hardly a book or newspaper was printed. José Maria Braga, an early 20th century historian and scholar, son of ‘Hongkong Telegraph’ manager José Pedro Braga, who appears in our feature on the Portuguese community in Hong Kong on p70, recounts in his book ‘The Beginnings of Printing at Macau’: “It was not until two hundred years later that printing again began at Macao save a few books produced by the xylographic process.”

Newspaper printing started in 1822 with the ‘Abelha da China’ periodical, which literally means ‘China Bee’, that ran for just over a year. The recent exhibition at the Senado Library showcased original prints of the Macao gazette, as well as Latin-Chinese and Chinese-Portuguese dictionaries from the period.

At this early stage, we can already see how readily presses were moved around the region. ‘The Canton Register’, one of the earliest newspapers, was printed for six months of the year in Canton and then, at the end of every trading period when the merchants had to leave Canton, it was published in Macao. Then, 1841 saw the cession of Hong Kong to the British. Printers started to move their operations to the new territory at this point to fulfil the demand for newspapers and financial journals in this growing trading port. This marked the beginning of the spread of modern printing technology across the Pearl River Delta.

Dr Stella Lee Shuk Yee, who curated the Senado Library exhibition, holds a PhD in Literature and Art from Jinan University in Guangzhou and currently works as a researcher of rare books in foreign languages at the Macao Public Library. She talks us through the exhibits with pride and enthusiasm. She reveals: “Printing was a way to make money for many of the people in Macao of the time. From 1843, Macao was declining as Hong Kong was building up. English speaking missionaries would travel to Hong Kong for business, so Macao was losing the role of the business hub for the West.” Dr Lee adds that ‘several newspapers appeared in Hong Kong’ due to good relations between the English and the French and Portuguese.

Dr Lee wears gloves to protect the delicate pages of the relics as she turns them and adds: “Education was important as printing was a great job to have. The Macao people found opportunities as translators from English to Chinese. Doing business as a secretary in Hong Kong was a good job to have.”

A treaty between Portugal and China in 1888 warmed relations in the region and newspaper printing started to spread into China, through word of mouth and personal connections. “1893 saw the first casting of Chinese movable type,” says Dr Lee. “There were more Chinese characters and more interest in the technology throughout China. The spread was accelerated by London missionaries [from the London Missionary Society]. With the industrial revolution in full swing, the English were moving everything from handmade to mass production.”

Showing us books printed in the late 19th century, Dr Lee tells the story of Wong To, a Macanese printing expert who helped London missionaries translate and print books in Chinese, until they closed their company. Then he grasped the opportunity and bought the press himself. “He became a tycoon in printing in Hong Kong and, then, Shanghai,” says Dr Lee. “He was the first journalist who published a Chinese newspaper. He was from Shanghai and printing was booming, so he returned and made his name as a big tycoon.”

In the early 20th century, Western printing was spreading throughout China but political tensions, once again, took their toll in Macao. Dr Lee explains: “Political problems with the Ch’ing (Qing) government meant many people in Macao fled to other European colonies such as Jakarta, Malacca and Singapore, where they built new printing equipment or used old machines from Canton.”

She continues: “Many Asian countries had a close relationship with Macao because whenever something didn’t work in one place, they would move to another place. Macao was a place of shelter for many people.” This movement between colonial outposts accounts for the further spread of Western printing technology throughout the East from Macao.

A nation of entrepreneurs

Macao’s role in the spread of printing technology is a story of the territory’s entrepreneurship in shaping the future of the East. Economic, political and religious factors interplayed to deliver Gutenberg’s invention throughout the region. Macao acted as a place of shelter for many and a hub of business to the West.

As we prepare to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the SAR in December, the rare books and precious periodicals in this collection are a testament to the enduring spirit of this city, so influential in regional and world history. Macao most certainly played a vital role in a technological revolution that transformed human history and how we read, record and communicate.