The exhibition explores some of the themes that characterise Renaissance art (14th to 17th centuries) from the human form to movement, light and shade and costume.

Thanks to a collaboration between the British Museum and the Macao Museum of Art, the people of Macao have their first chance to see rare drawings from the Italian Renaissance, including some by three of the world’s most famous artists: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

This handpicked collection of 52 drawings by 42 different masters from 1470 to 1580, on loan from the British Museum (BM), offers a rare glimpse into the artistic process underpinning one of the most transformational periods in art history. Opened 11 April, the exhibition runs to 30 June.

“Drawings were intended as private working studies for the use of the artist and his assistants in the studio,” said Sarah Vowles, the exhibition curator from the BM. “They were not meant to be circulated among those outside this circle, and it is this very fact which makes them so intriguing, as they offer an insight into the thoughts and decision-making process of their creators.”

She said that it is a miracle that these delicate pieces had survived more than 500 years. “They have been preserved in portfolios, in drawers and albums with no light. That tells us about the care and love of their collectors.”

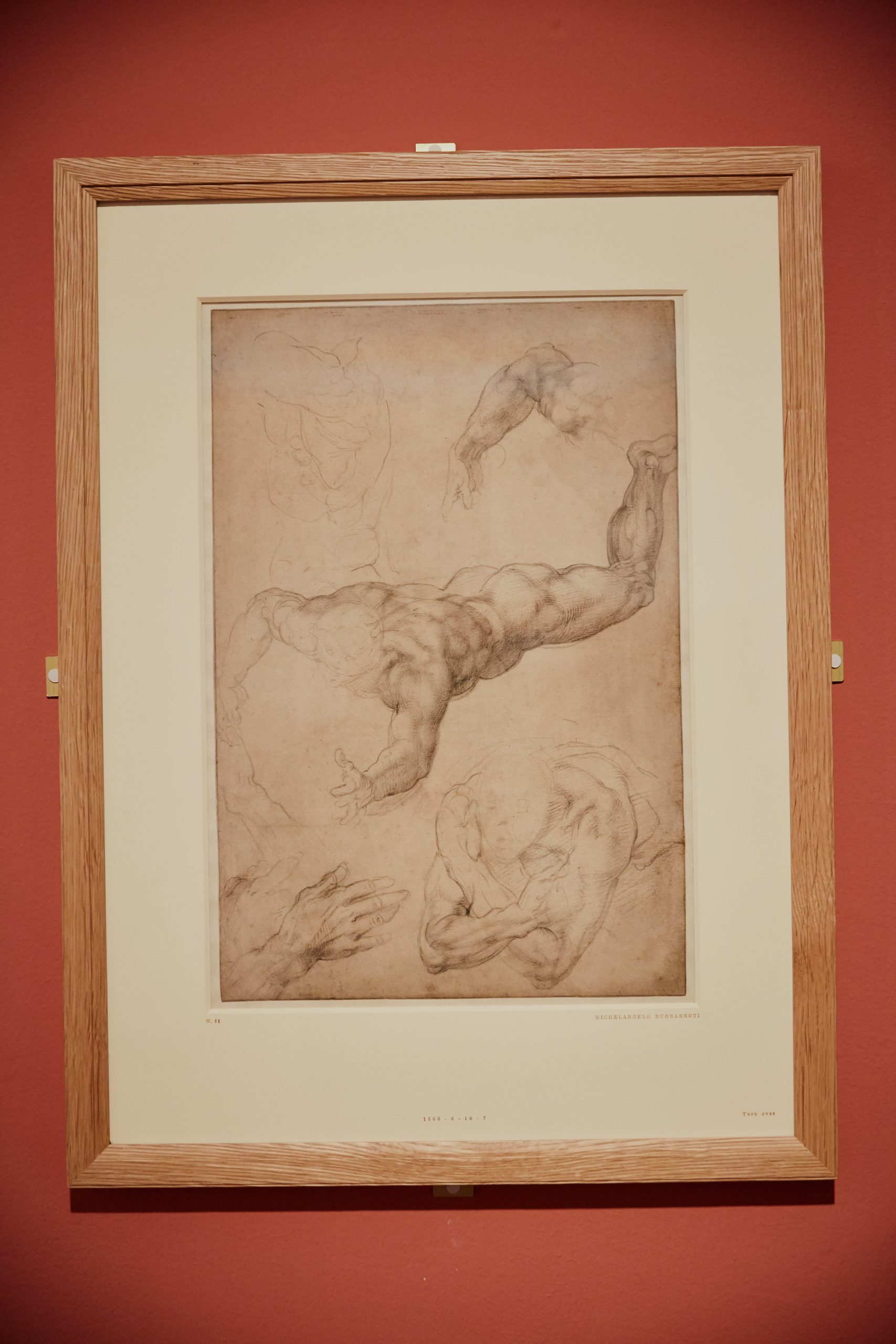

Among the collection is a drawing of a male figure, made by Michelangelo in preparation for an angel in the Last Judgement, a sprawling fresco adorning the altar wall of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel. “He had to get everything right in advance, because fresco is a challenging technique. Since it must be painted onto wet plaster, which dries very quickly, the artist only has one chance.”

Next to it are two caricatures by Leonardo da Vinci, among the earliest works of this kind. “These eccentric works have always been very popular with visitors and collectors,” commented Vowles.

Then there is a drawing by Michelangelo of the Annunciation, the moment when the archangel Gabriel tells Mary she is to give birth to the Son of God. “Michelangelo was an intensely spiritual man and here he tries to show the psychology of Mary as she is given this astonishing news,” Vowles explained. “You can see how he combines the majesty and dignity of her figure with vulnerability and surprise. It is a remarkably intimate conception of the scene.”

Global reach

Founded in 1753, the British Museum was the first institution to be established as a public museum and it remains one of the great museums of the world. With the exception of the two World Wars, it has remained in operation and free to the public since opening in 1759. The collection boasts eight million pieces, ranging from rock tools used by our ancestors in Africa around 1.8 million years ago to contemporary art works, and it continues to actively collect.

While some countries in Africa and Asia have called for the return of objects held in the collections of major European museums, Vowles contends that the BM is committed to researching and establishing the circumstances in which its objects were acquired.

She also points to touring exhibitions like the one at the Macao Museum of Art (MAM), as well as the museum’s training, outreach, events and community programmes, as examples of their effort to share the vast BM collection with the world (only about one per cent of the pieces are on display at any one time).

“We allow visitors from across the world to encounter their own cultures within the context of the whole history of the world,” Vowles said. Six million people visit the museum each year, and many more access the collection through “the most detailed online database of any museum.”

Last October, the BM opened a shop at the Ping An Financial Centre in Shenzhen. It is committed to sharing its extensive collection and, in 2018, loaned 4,700 objects to other museums in Britain and overseas – more than any other museum, Vowles noted.

About 18 months ago, MAM approached the BM about the possibility of collaborating to present this exhibition of drawings. “The exhibition went to Suzhou Museum in 2015,” she said. “We added three more drawings especially for Macao, including the drawing for the Last Judgement.” The BM has around 50,000 drawings, dating from the 14th century up through the present day.

With one of the best collections of Italian Renaissance drawings in the world, choosing which to include was a challenge. Vowles and her colleagues decided to focus on introducing Chinese visitors to some of the great names of Western art history. “But we had to make a careful selection of our drawings. Due to the fragility of these works, they can only be exhibited for a total of 12 months every 10 years.”

Organised into six themes – the Human Figure, Movement, Light, Costume and Drapery, the Natural World, and Storytelling – the selected pieces allow visitors to follow the training of a young Renaissance artist, and to understand the primacy of drawing in the artistic processes of the time. “You can see how the artists develop their skills through this increasing complexity.”

Before the Renaissance, almost all art was religious. Yet, during the 15th and 16th centuries, artists and scholars begin to engage passionately with relics of the classical world.

Sarah Vowles

Vowles believes this exhibition will have particular resonance with Chinese audiences: “[They] have a great affinity with works on paper, due to their rich artistic heritage which includes paintings on paper scrolls and beautiful calligraphy.”

Recapturing reality

The Renaissance saw a revolution in art. “Before the Renaissance, almost all art was religious,” said Vowles. “Yet, during the 15th and 16th centuries, artists and scholars begin to engage passionately with relics of the classical world. Wealthy connoisseurs assembled collections of Roman statues, which were often made available for study, and we see increased popularity of classical mythological subjects in art.

“There was also an important technical shift. From the beginning of the 15th century, new technologies led to the establishment of a paper-making industry in Italy, based on techniques originally imported from China. From the 1460s, with the introduction of the printing press from Germany, there was increased demand for a more plentiful and cheaper supply of paper. Thanks to the greater availability of paper, drawing became an increasingly common and central aspect of a young artist’s training – and, crucially, more drawings could be preserved.”

By studying through drawing, artists learned to render light and shade to create relief, the convincing fall of drapery, and the accurate structure of the human body. “For Leonardo da Vinci, especially, drawings were an absolutely essential tool with which to understand the workings of the human body and countless aspects of nature – from the beating of a bird’s wing to the flow of water,” she said.

Renaissance artists created for the first time the illusion of three-dimensional space on two-dimensional materials. The development of linear perspective in the Early Renaissance allowed for more naturalistic and engaging images, while the Mannerist style of the High Renaissance turned the same techniques toward creating artificial extremes.

In his introduction to the exhibition, British Museum Director Hartwig Fischer described how “the exhibition underlines how the perfection of the finished work, whether in paint or some other medium, depended on many hours of preparation in the artist’s studio through making drawing after drawing.”

Hartwig offered up a Titian piece as an example. The black and white chalk study on blue paper “allows us to share the moment when the Venetian master found the angle of the head, and the distribution of light, that expresses the fervent joy of one of the saints watching the figure of the Virgin Mary carried to heaven on a cloud above his head,” Fischer said.

Other drawings included in the exhibition demonstrate the blossoming of subject matter in this period, particularly from Titian’s fellow Mannerist painters. A drawing by Giulio Romano depicts an ostrich, an extremely rare bird in Europe at that time; he likely saw it in the menagerie of his patron, the Duke of Mantua. It exemplifies the thirst for knowledge, and the fascination of exotic cultures, that characterised this intellectually fertile period.

Another drawing shows a mulberry tree, from which farmers pick leaves to feed their silkworms. Silk Road traders had brought silk fabrics from China since antiquity, but in the 15th century, Florence developed its own important centre of silk production.

“Taddeo Zuccaro painted this scene of silk manufacture in the dressing room of Cardinal Farnese, one of the great Renaissance patrons. This is a preparatory study for that painting. As the Cardinal got dressed in his expensive robes, he could be reminded of how these valuable fabrics came to be produced,” Vowles said.

In Italy at that time, she explained, there were strict rules governing who could wear which kinds of fabrics and what colours; they signified the status of the wearer. Cardinals such as Farnese dressed in crimson and scarlet; very wealthy laymen in Venice wore black, which was the most expensive of all pigments.

The exhibition also features a rare drawing of a female nude by Rosso Fiorentino. The customs of the Renaissance prevented respectable women from posing in the nude. “In Italy, artists might have to resort to hiring a prostitute to model nude. However, this could be expensive and, since most figures were ultimately clothed, painters often used male models to pose for female figures, later adapting them in the paintings – with various degrees of success,” said Vowles.

These drawings, while commonly produced at the time, only survived to the present day because they were donated to friends or patrons and kept in studios as works of reference. By the 16th century, connoisseurs began to collect drawings for their beauty or for aesthetic reasons.

Modern take on old masters

Students from the Creative Industries Faculty of the University of Saint Joseph embraced the transitory nature of most preparatory drawings in their homages to the three most famous artists on display: Raphael, Michelangelo, and Leonardo da Vinci.

Rather than paper, the sculptures are fashioned out of one of the most common materials of this era: plastic. After the exhibition, the pieces will be melted down and re-used.

Margarida Saraiva, resident curator of MAM, explained that they “wanted to involve the students in the process. This is an important moment, with the museum celebrating its 20th anniversary this year. It is rare for us to have works by some of the most famous artists in the world.”

This year also marks the 500th anniversary of the passing of Leonardo; the exhibition opened in April to mark his birthday, on 15 April.

Visitors can browse the exhibition on their own or take advantage of guided tours with Saraiva, hands-on tours to the 3D printing section, drawing workshops, courses, and special activities for children, the blind and visually impaired.