A few decades ago, children in Macao didn’t turn to their phones, tablets or TVs for entertainment after school. Instead they rushed to the nearest street vendor selling dough sculptures.

Included as one of Macao’s 70 ‘Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage’ items, dough sculptures originated from northern China, and can be traced back to the Han dynasty (202 – 220 BC).

Dough sculptures in the past were mainly used as edible ornaments, decorations or religious figurines in worship rituals, weddings and harvest celebrations. In this folk art, dough is steamed, dyed and sculpted into figurines of Chinese deities, historical figures and more.

In the 20th century, they became popular toys for children. Today, however, only a few people still make dough sculptures. Macao-born Lam Iok Hoi is one of them – and he might be the only one doing it as a professional artist. Although the 73-year-old spent his whole life working as a chef, Lam no longer toils in the kitchen. Now he keeps his hands busy preserving this dying art.

DEVELOPING PERSISTENCE

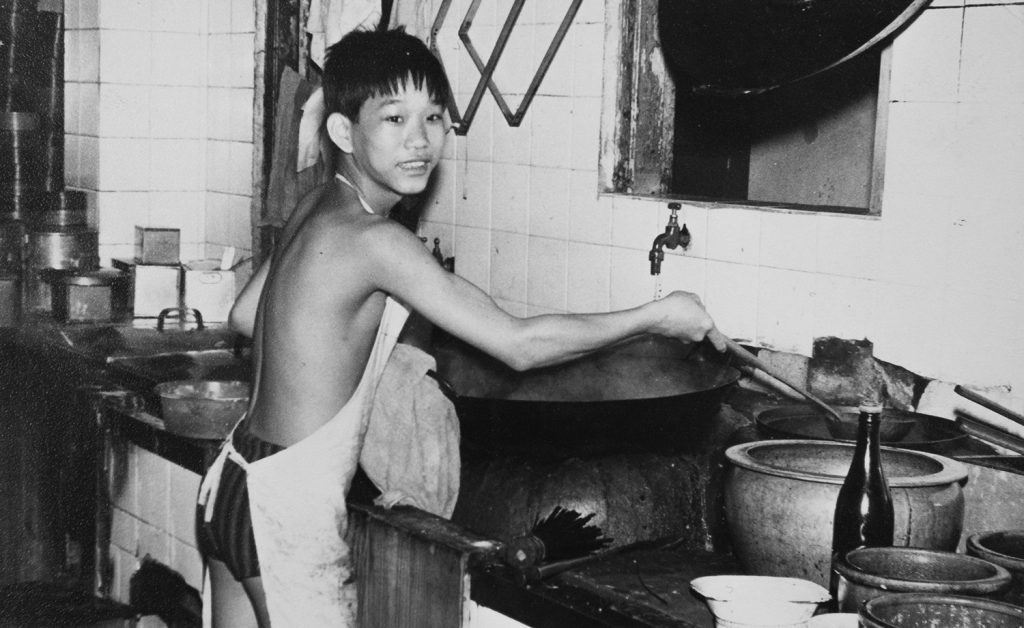

Lam had a challenging early life. He lost his mother when he was only 3 years old, and his father passed away not long after, forcing him to grow up in an orphanage in Macao. By the time he was 13, he’d already begun working in a Chinese restaurant – an age that might seem young now, but was common in the early 1960s, when Lam was coming of age.

He started out cleaning the restaurant’s kitchen and toilet before moving up to cleaning utensils. Eventually, he began to learn how to make dim sum. By the time he was 17, he was living by himself, making ends meet. “I didn’t think about anything at that time. No matter how hard [the work] was, it was for me to survive. I just focused on living and making it,” he says.

While other children rushed to buy dough sculptures after school, he did not have that luxury. But in a twist, while his childhood shaped his persistence, his career would spark his interest in dough sculptures.

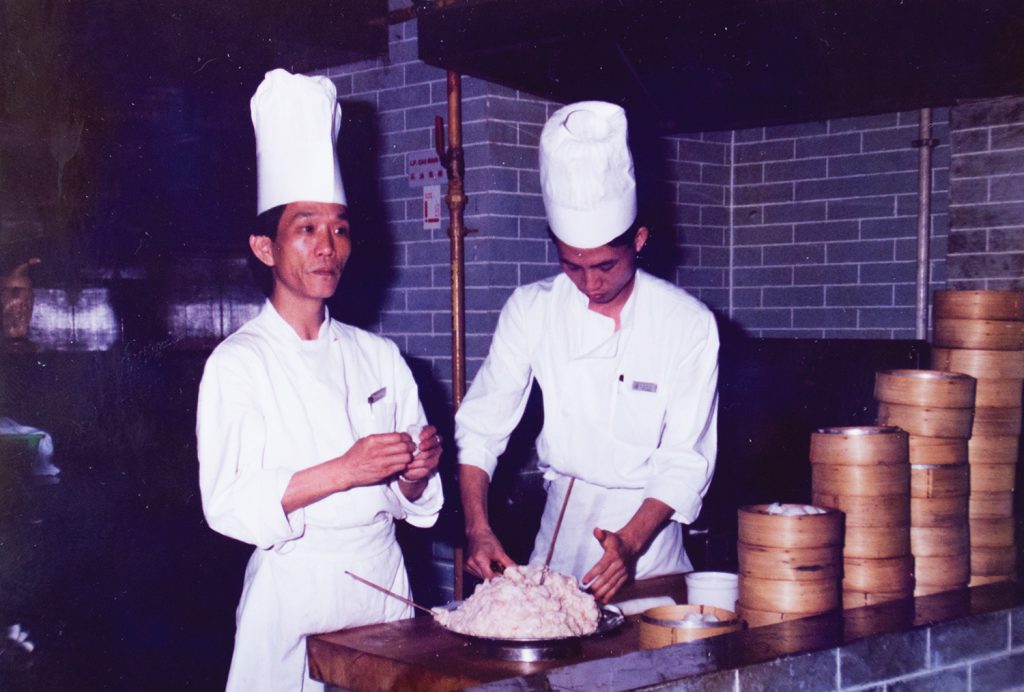

Over the years, Lam worked his way up the ranks, moving from local restaurants like Dak Loi, Diamond Restaurant and Golden Crown Restaurants that were popular in the 1960s to Zhuhai Gongbei Palace Hotel and the five-star Yindo Hotel Zhuhai, where he was the Dim Sum Head Chef for 10 years. He also worked at Mondial Hotel, Hotel Lisboa’s Portas do Sol restaurant, Casa Real Hotel and the Zi Yat Heen restaurant at Four Seasons Macao, where he had a brief stint in 2010 as the restaurant’s Second Dim Sum Chef shortly before he retired.

In the mid-1980s, in the heart of his career as a chef, he began to make dough sculptures as garnishes for his dim sum dishes. “As a chef, besides the cooking techniques, we must also make our dishes more attractive, so I had to keep coming up with new ideas,” he says.

“I learned to make dough sculptures by myself, and I kept on practising purely for my dim sum dishes.” In time, however, this work-driven pursuit became something more. Eventually, a desire to keep the dough sculpture tradition alive drove Lam to do more with the forgotten practice.

RELIVING CHILDHOOD MEMORIES

After Lam retired as a chef about a decade ago, he started making dough sculptures more regularly, dedicating himself to promoting the art. He made a name for himself doing it, too. Soon, he started teaching workshops in Macao to help others learn the craft, earning the support of the Cultural Affairs Bureau in the process. He has even garnered a measure of fame for his work in the surrounding regions. He says he has travelled across cities like Zhuhai, Dongguan, Foshan and Guangzhou, as well as Hong Kong, to make his sculptures at events like bazaars, festivals and carnivals, or workshops.

“I like making the dough sculptures as an artist more than as a chef because I can show different types of figurines rather than just food-related sculptures,” says Lam. Those include figurines of dragon dance teams and Chinese deities, such as Guan Gong (a military general during China’s late Eastern Han dynasty), Zhong Kui (the ‘vanquisher of ghosts and evil beings’, often seen as a large man with a big black beard and bulging eyes) and the Cloth-Sack Monk (also known as the Laughing Buddha).

“When I made dough sculptures as garnishes, I would only get praise from some of the restaurant guests, but now doing it as an artist, teaching children in workshops, I get to earn money,” Lam admits.

Lam has so far taught around 2,000 children in the workshops he’s led over the past 10 years (usually, he leads about 15 each year). All his students have been children, from the very young to teenagers. “The children have subsidies [for art workshops] from the government. Adults wouldn’t pay to learn this,” he jokes.

But Lam admits that he loves teaching children anyway. “They are open-minded and pure. Children follow instructions and they are naturally happy, so it makes me happy to teach them.”

He has even been invited to lead workshops in the mainland, where he says he’s found a deeply engaged audience. “The students in the mainland have to pay to join workshops so most of them will really attend the classes, whereas in Macao most workshops are sponsored by the government,” he says. “[Here] students often only register and do not turn up to classes.”

FROM NORTHERN CHINA TO MACAO

A long time ago in northern China, the dough sculptures, beautiful as they were, could actually be eaten, a feature that still existed in Macao’s dough sculptures a few decades back. But people these days add preservatives to the dough.

According to Lam, most dough sculptures these days are purposely made inedible so they can last longer than they did long ago, when they were made with plain dough and natural food colouring. Now they can be kept for up to 20 years if placed in an acrylic box to avoid humidity. They are also used purely for decorations these days.

“People don’t want to throw the sculptures away after being used [once] just for a short period of time,” he says.

Even though the traditions have changed in modern times, Lam intends to see this dying artform preserved in Macao, both the time-honoured techniques and history. But it may be a tough mission. He says most of his students are not interested in making traditional figurines like the ones Lam grew up with. “They prefer to learn how to make something like Hello Kitty,” the fictional Japanese Bobtail cat character, he says.

Personally, Lam prefers teaching how to make traditional dough sculptures – the kinds he continues to make in his free time.

“This art has more than 2,000 years of history. My hope is to get more people to learn it and pass it down [to future generations].”

Despite his best efforts, Lam is not sure about its future in his hometown, where few seem interested in even buying a small dough sculpture for MOP 30-90, let alone bigger ones that can cost a couple of hundred of patacas each.

Lam also notes that there is not an association to officially promote the craft. “Nobody else is doing this. I’m the only one [trying to preserve this as a craft] so there is no association for it. Sometimes, I’m invited by the government to join exhibitions, but I always join without any association support,” he says.

“There are some multi-art associations in Macao, but none include the art of making dough sculptures.”

Nevertheless, Lam has no intention to give up his mission. “Hopefully, among the students I have taught, there will be some who will continue preserving this art so that it can be passed down.”

He also hopes that the government will continue to support its promotion in Macao to generate interest among the generations to come, which include his two young grandchildren.

“Neither of my two sons know anything about this art, but my grandson and granddaughter know a little bit about making dough sculptures,” so there may be hope for its future after all, he says.

This art of dough sculptures could be a cheap hobby for people to pursue now, as the pandemic continues to force many of us to shelter at home. Even though in-person workshops might be suspended, you can still have fun at home with family, learning to make the dough while experimenting with your sculptures.

“Of course, it takes time for your creations to become good, [but] it’s easy to make the dough and it’s not that hard to learn to make the sculptures,” Lam says.