TEXT Morse Lei, Executive Director of CSR Macao

The government intends to support the development of an integrated organic waste valorisation strategy for Macao, by reviewing Macao’s existing waste recycling programme.

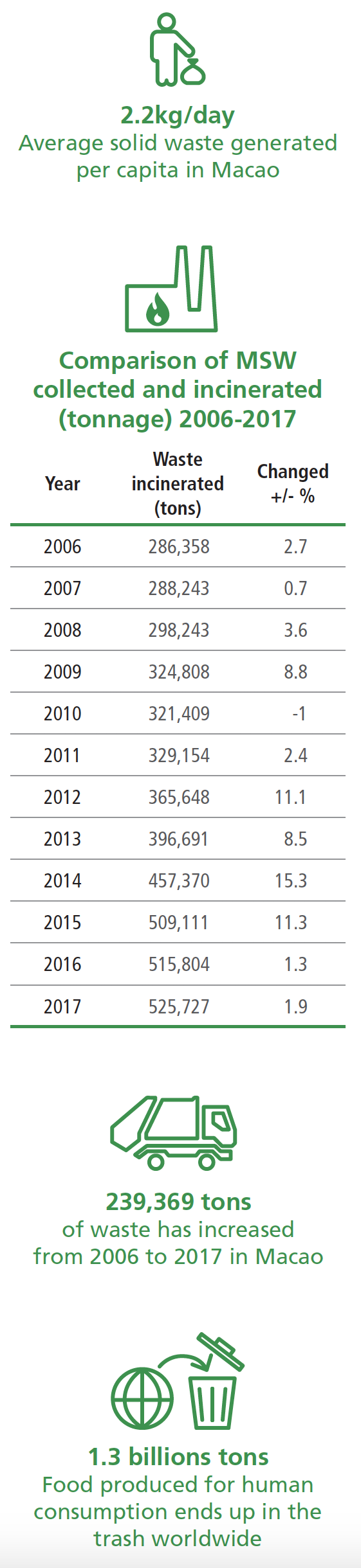

For such a small city, Macao generates a lot of waste. Between 2006 and 2017, the amount of municipal solid waste (MSW) generated in the city increased by a whopping 83.5 per cent – more than three times the population increase during the same period.

This increase has been attributed to the city’s rapid economic development and to the lack of alternative waste management valorisation strategies – schemes to reuse, recycle or compost waste into something of value, such as raw materials. In 2017, the average per capita rate of solid waste generated was 2.2 kg per day, up nearly 44 per cent from 2006.

More than half of that waste is organic, biodegradable waste derived from plants or animals, most of which is food thrown out by residents and commercial entities. This isn’t unique to Macao: each year, roughly one‑third of food – around 1.3 billion tons – produced for human consumption worldwide ends up in the trash.

Solid waste challenges

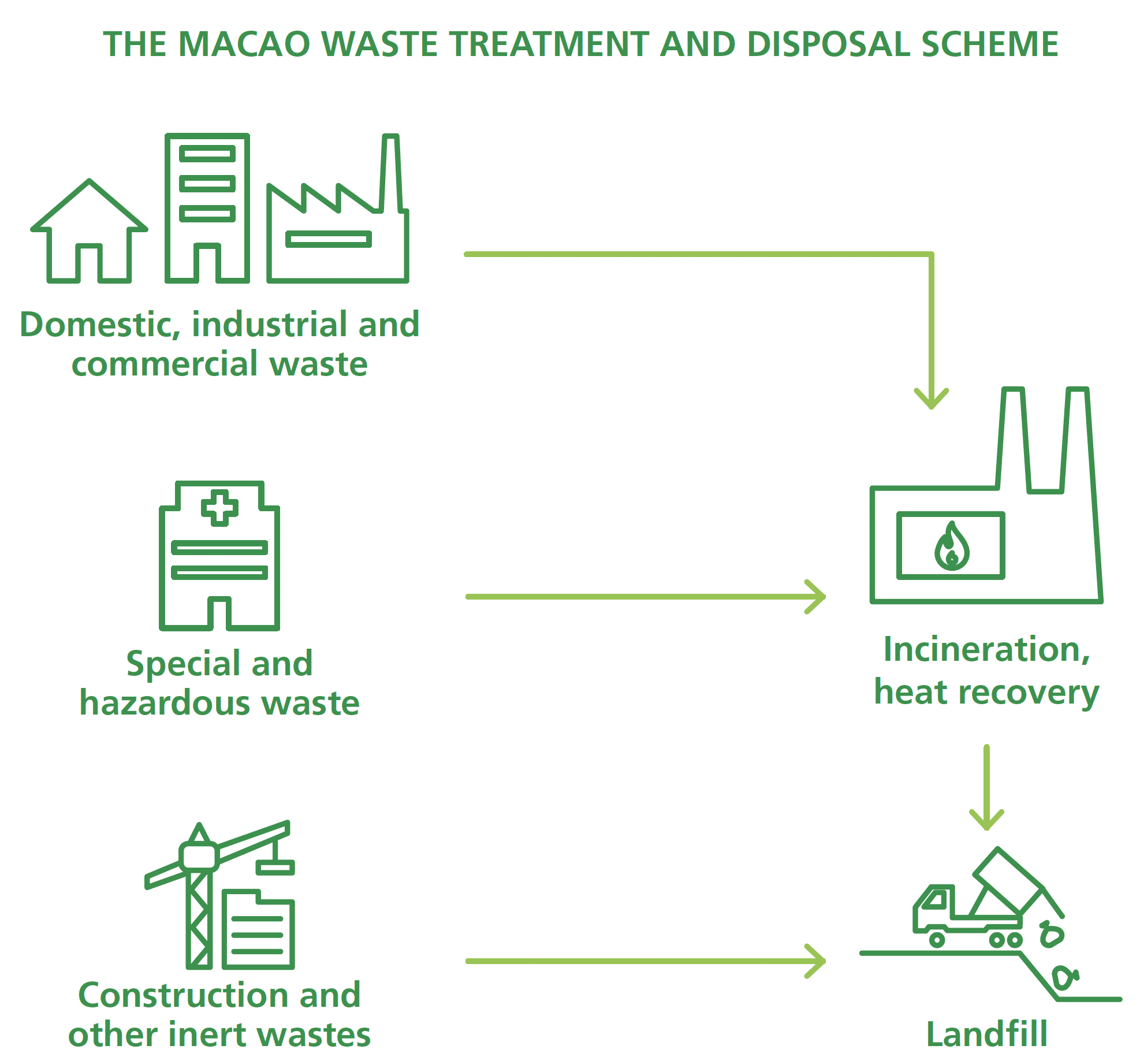

Macao MSW treatment is primarily focused on energy recovery by incineration, with the existing Macao Solid Waste Incineration Centre’s annual capacity at 630,720 tons. As the amount of MSW increases, the facility will soon reach design capacity, necessitating increased capacity and new strategies to tackle solid waste management.

Today, Macao sends most of its waste – including special waste with heat values (the energy produced through combustion) – to be incinerated for energy recovery. Non‑combustible special waste is treated at the Special Hazardous Waste Treatment Station with neutralisation or solidification, and further disposed together with inert construction waste at landfill. The lightweight fly ash and heavier bottom ash produced during incineration are also sent to the controlled landfill.

Within this scheme, the makeup of Macao MSW matters: having more than 50 per cent organic waste leads to a high moisture level that negatively impacts the performance of the incineration plant and the capacity utilisation of the local landfill.

One possible solution is organic waste valorisation by source separate collection and application of the latest technology, such as anaerobic digestion, which breaks down organic waste in an oxygen‑free environment to produce biogas and biofertilizers.

Processes like this could provide a critical tool in combatting the growing waste volumes being generated in the city. It would also offer a source of renewable energy and an organic soil conditioner.

Although Macao is currently composting its food waste, the daily tonnage is still less than 1 per cent of the organic waste generated. As such, the government intends to support the development of an integrated organic waste valorisation strategy for Macao, by reviewing Macao’s existing waste recycling programme.

It shall also consider some areas of focus for future efforts: developing a new methodology for source separation of organic waste; encouraging and implementing source separation of organic waste; treating all organic waste together; reducing the volume of MSW to be incinerated; jointly handling the municipal waste water sludge in circular technologies for energy recovery; reusing and valorising waste water; and lastly, using the digestate (product of anaerobic digestion) for composting to recover nutrients for soil amendment or solid fuel.

Producer‑pay system

Another method for tackling increased MSW is to reduce it at the source. Macao categorises MSW into industrial, commercial, and domestic waste. Collection for domestic waste is paid for by the government, at no charge to residents.

Conversely, industrial and commercial waste producers operate on a producer‑pay system which requires producers to pay collection companies directly. Since producers pay based on the amount of waste collected, there is a financial incentive to reduce waste generation.

With the increase in domestic waste, Macao should consider the producer‑pay system – more commonly known as pay‑as‑you‑throw – for all domestic waste producers.

Similar to the ‘polluter pays’ principle, this scheme encourages people in Macao to produce less waste and helps divert waste from landfill or incineration towards a circular economy. Where in a linear economy, products go from manufacture, to use, to waste, a circular economy works to reduce waste to a minimum and reuse, repair, and recycle existing products and materials.

A study conducted in 2016 found 95.7 per cent of Macao people reported a willingness to sort solid waste at home, if the government required them to do so.

The shift from extraction and consumption to renewal and restoration has been gaining ground in recent years, with countries around the world developing roadmaps for material recovery on a grand scale. This July, China signed a memorandum of understanding on the circular economy with the EU, paving the way for the two economies to co‑operate and coordinate their efforts to minimise waste and optimise resource use.

Macao appears similarly willing to work on a more local scale: a study conducted in 2016 found 95.7 per cent of Macao people reported a willingness to sort solid waste at home, if the government required them to do so. The pay‑as‑you‑throw scheme also netted an overwhelmingly positive response – 85.4 per cent – indicating that implementation of both would likely be embraced by the public.

Designing a new system

The existing collection practices in Macao rely on compaction containers or rear‑end loader compaction vehicles collecting mixed waste. While this approach does reduce the overall volume of waste, it also makes it far more difficult to sort waste afterwards.

Implementing a source separate collection method offers the simplest solution to extracting organic waste for valorisation. Charging people for collection based on the amount of waste they produce would also discourage avoidable food waste and minimise the food surplus.

This approach to organic waste sorting would complement the existing waste‑to‑energy treatment of incineration by reducing the moisture content in the waste, while also generating revenue through further valorisation. Biogas would add to energy recovery, rather than hindering the regular incineration process, and organic fertilisers could be used to improve soil quality rather than adding to the landfill.

A simple solution on paper, such a scheme nonetheless can only be achieved with a great investment in a strategic education and information for residents, with a supportive and inclusive approach. Should the Macao government adopt this possible solution to the issue of MSW in Macao, setting up a collection methodology and policy on how to implement Source Separate Organic Waste (SSOW) would be critical. Without adequate education and public campaigns for SSOW, targeted at both residents and commercial entities, this effort would not succeed.