TEXT Lucian Hoi

Macao will soon boldly go where it has never gone before: space. The city’s first satellite is getting ready for launch and it should put the SAR on the global space technology map while also giving crucial geomagnetic data that will benefit the whole world.

Before 1957, the night sky had barely been touched by humankind. But on 4 October that year, the Soviet Union successfully launched the world’s first artificial satellite into space and history was forever changed. Sputnik 1 was about the size of a beach ball and took around 98 minutes to orbit the Earth on its elliptical path. It carried no scientific instruments, however it did send radio signals back to the ground for a short period, meaning there was nevertheless much to learn from the first man-made object to orbit the planet.

Since that iconic day, thousands of artificial satellites have been launched into space and it is believed that there are now more than 2,000 of them orbiting the Earth that are fully operational. And, like Sputnik, they all perform one or many functions that help us down on the ground to learn about the planet, the solar system and the universe as a whole. Some experts predict many thousands more will be launched over the coming years as private companies send satellites up into the sky like technology entrepreneur and SpaceX boss Elon Musk did in March as he sent a sixth load of 60 Starlink satellites into orbit. However, not only has the number of satellites in orbit surged over the past few decades but also the number of countries and regions behind this space odyssey. And this elite list of backers will soon welcome a new name: Macao.

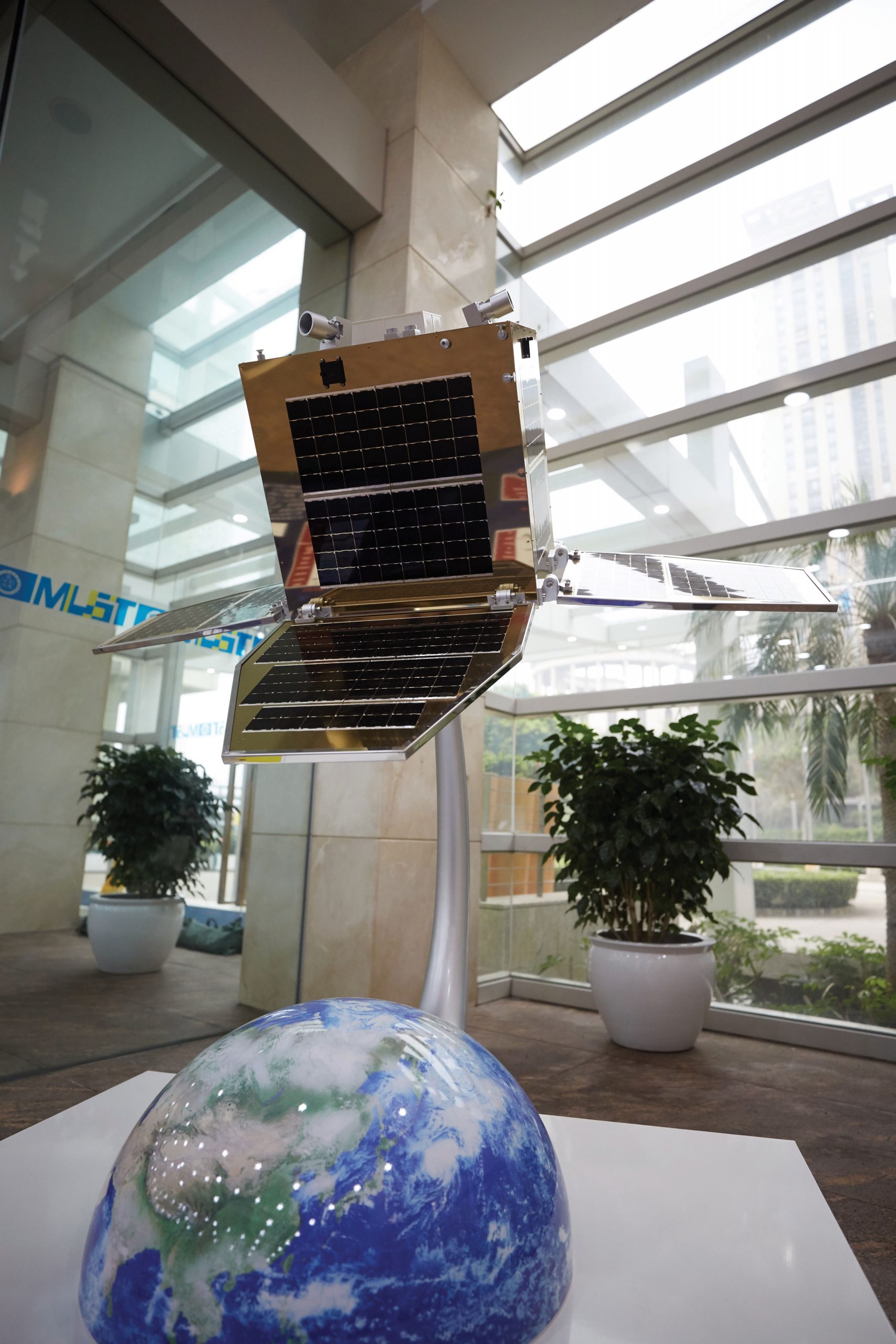

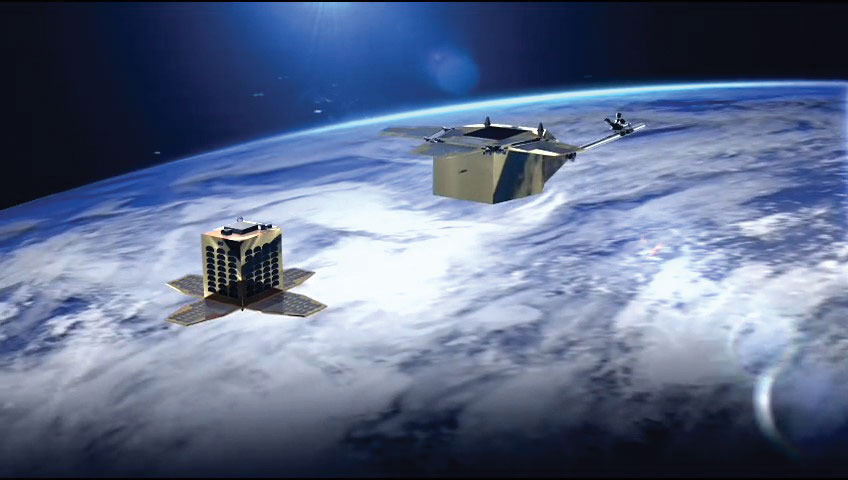

With support from the local and central governments, the State Key Laboratory of Lunar and Planetary Science (SKLplanets) at the Macau University of Science and Technology (MUST) has been developing the city’s first satellite – named Macao Science 1 – since 2018. The world’s first and only scientific exploration satellite to be placed in a near-equatorial orbit to monitor the geomagnetic field and space environment of the near-equator South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA), the project marks a milestone for the local development of aerospace technology.

Despite the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Professor Zhang Keke, who is the chair professor and director of SKLplanets, finds time to speak to us about the project on MUST’s campus, which is almost deserted as we meet during lockdown. And although he wears a facemask throughout our interview – only taking it off for a photoshoot – it’s clear he is hugely excited about Macao Science 1. “There has possibly never been a scientific research project in Macao that will have such an enormous impact nationally and globally,” he tells us.

There has possibly never been a scientific research project in Macao that will have such an enormous impact nationally and globally.

Prof Zhang has more than three decades’ worth of experience in planetary physics and astronomy, so his words carry great weight. He has worked at a range of universities and research institutions during his life and he has also headed up multiple research projects in the US, UK and China over his acclaimed career, including a stint as director of the Centre for Geophysical and Astrophysical Fluid Dynamics College at the UK’s University of Exeter. The professor, who received a Royal Astronomical Society Group Achievement Award for his work in magnetohydrodynamics as part of a team in 2013, was appointed director of SKLplanets in July 2018. He is now the chief scientist on the satellite initiative. “This project,” he says, “is of paramount importance: Macao needs it and so does Mainland China and the rest of the world.”

Protective umbrella

To get a clear grasp of the significance of Macao Science 1, the geomagnetic field – the magnetic field of the Earth – first needs to be understood. In the words of Prof Zhang, this field serves as ‘an umbrella’ to protect us and all life on the Earth from solar wind, a continuous stream of charged particles released from the Sun. “The geomagnetic field is key to the survival of mankind,” says the renowned astrophysicist. “You can’t see it but it is everywhere. It is also crucial in our daily life nowadays when it comes to national defence, mining, space weather forecasting, navigation and so on.”

Although our ancestors acknowledged the existence of the Earth’s magnetic field more than 1,000 years ago, satellites were only first deployed for monitoring and studying it about two decades ago. “Satellites could cover every corner of the Earth,” says Prof Zhang, “giving us more detailed information about the geomagnetic field from its structure and its origin to its changes [over time].” The latest example of sending up satellites to do just that was the Swarm mission – which was made up of a constellation of three satellites – that was launched by the European Space Agency in 2013. The satellites are still up in space studying the planet’s magnetic field. Macao Science 1, as Prof Zhang puts it, could ‘fill the blanks’ in the global study as it specifically focuses on the southern parts of the Atlantic Ocean, between South America and the southern tip of Africa, that make up the SAA.

The Earth’s magnetic field doesn’t just give us our north and south poles – it also protects us from solar winds and cosmic radiation. But scientists have found it is rapidly weakening and some believe it could soon flip, thus reversing the magnetic poles. This has happened before, with evidence it last happened almost 800,000 years ago. The region that gives scientists most concern is the SAA, which boasts a field so weak that it’s dangerous for satellites to enter it as the additional radiation it lets through could disrupt their electronics. Prof Zhang describes it as ‘a hole in the umbrella’ – hence the SKLplanets team’s great interest in this region. According to a spokesman for SKLplanets, Macao Science 1 could provide the team on the ground with highly accurate high-resolution and long-time vector magnetic data on the SAA, as well as information about the high-energy particles in the region. This data can then be applied to all sorts of diverse areas of scientific interest.

The China National Space Administration attaches great importance to Macao’s development in the field of space science and technology.

Macao Science 1 is made up of two major parts, each containing hi-tech equipment. Part A is the main section which consists of a 3.7-metre non-magnetic boom and an optical platform that sports graphics in the shape of a lotus to symbolise Macao. The total length of the satellite is more than eight metres and it weighs about 500 kilograms. It’s made up of an array of components, materials and parts like, says the team behind it, ‘the making of a vehicle’.

Multinational ties

Macao is a city with a land area of just over 30 square kilometres. It is known for its world-class services industry, its tourism and its unique culture. It is not known for its interest in space – but this project could change all that. And the city has had plenty of helping hands while it prepares to embark on its cosmic journey. The development of the satellite relies on the backing of – and collaboration with – Mainland China, which has ascended to become one of the world’s major aerospace powers. Executed by SKLplanets, the Macao project is co-organised by the China National Space Administration (CNSA), the Macao government and the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in Macao – and it has also received the support of the Macao Foundation and China Space Foundation. The CNSA and Macao’s government consolidated their partnership by inking an agreement in December which will expedite the project.

In a ceremony marking the signing of the partnership agreement in December, Zhang Kejian, director of the CNSA, noted in his remarks that the satellite project ‘opened a new chapter’ of co-operation between Macao and the Mainland when it comes to astronomical technology. “The China National Space Administration,” he said, “attaches great importance to Macao’s development in the field of space science and technology, and encourages the science and technology community in Hong Kong and Macao to participate in national space projects.”

Besides the Macao Science 1 project and the 2018 establishment of SKLplanets – the first and only State Key Laboratory in the nation in the field of astronomy and planetary sciences under the approval and governing of the Ministry of Science and Technology – MUST has a relatively long history of engaging in national space projects. For instance, its scholars and researchers have been part of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Programme, an ongoing series of robotic Moon missions initiated by the CNSA, since 2005. Liu Liang, president of MUST, noted in the December ceremony that Macao could play to its strengths and become ‘a global gateway’ for the Chinese astronomy and aerospace sector and ‘a bridge’ for exchanges between the Mainland and the international community.

Sharing a similar perspective, Prof Zhang says the satellite project has attracted the participation of renowned institutions and experts from across the world. “Without the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ [principle in Macao], there would not be Macao Science 1,” he says, adding that during the development of the project SKLplanets has joined forces with, for instance, Harvard University in the US, the Danish National Space Centre, the University of Leeds and the University of Exeter in the UK and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland (ETH Zurich), as well as other international institutions.

Star trek

The development of satellites and space technology in Macao is beneficial, in general, to the city’s goal of diversifying its economy away from such heavy reliance on its glittering integrated gaming resorts. “Both the local administration and the central government have worked on steering Macao towards economic diversification,” says Prof Zhang, “but given its limited geographical size, the city could not just be another Shenzhen, with factories to manufacture goods. High technology is the way for the city to move forward and developing the area of astronomy does not require the need to have a lot of space, people and money.”

There are now nearly 100 scholars, researchers and postgraduate students in the SKLplanets team. The MUST team itself, which is made up of around 10 people, is headed by Prof Zhang and, along with leading figures from external institutions, it is in charge of the satellite project. Gathering experts from around the world, the team has great ambitions – launching Macao Science 1 is only the start of what the team envisages to turn the city into a global centre when it comes to geomagnetic field studies. “After the launch of the first satellite,” says Prof Zhang, “we plan to send three to four satellites in total to form a constellation which will monitor the geomagnetic field from different orbits, generating a huge amount of astronomical data.” To receive and process such data, the team plans to build a ground station and an astronomical data centre in the university. “Macao could dominate this area globally,” says Prof Zhang, “and we hope, in the future, any parties requiring relevant data will come to us.”

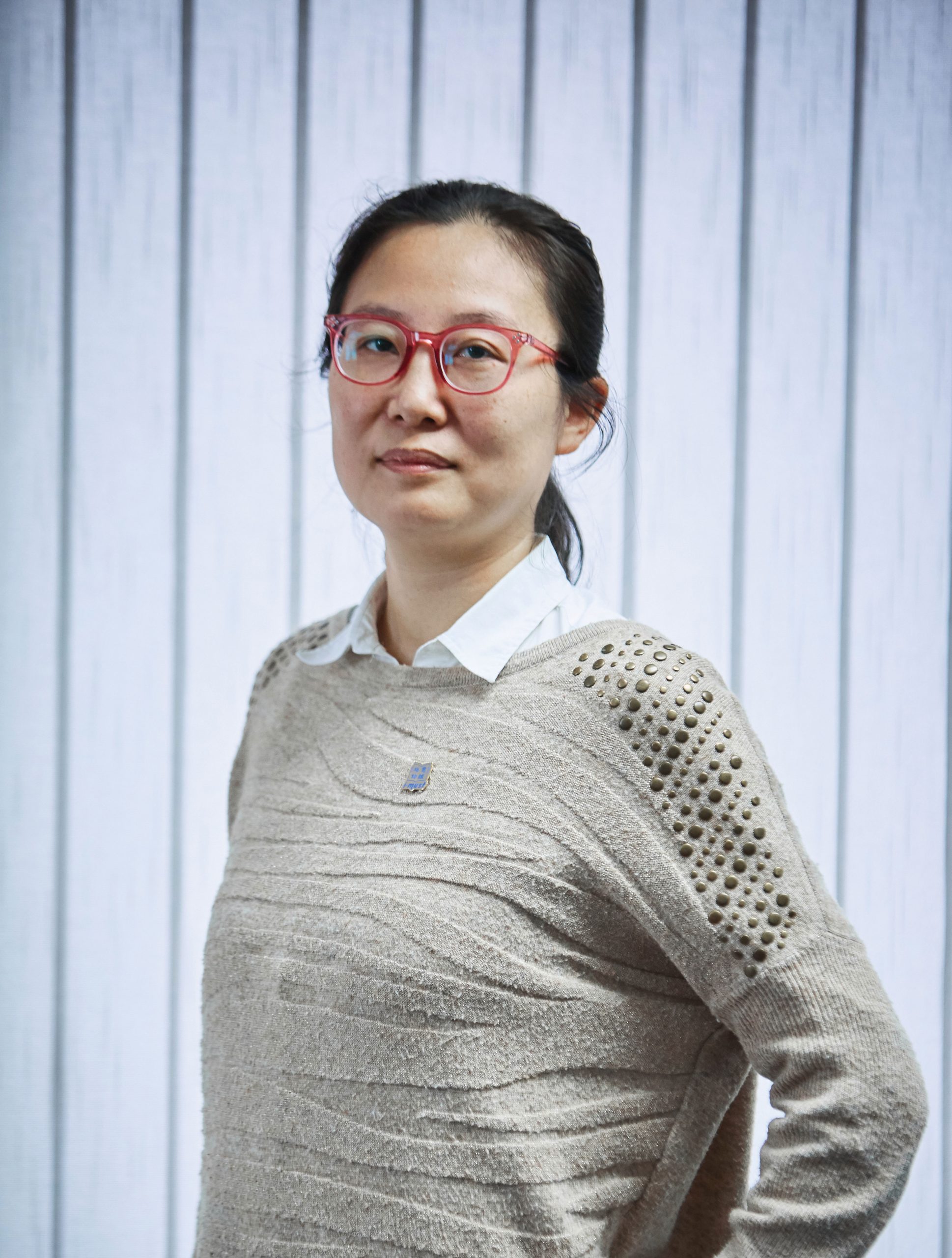

Xu Yi, assistant professor at SKLplanets, is part of the satellite team. Her recent work focuses on the application aspects of satellites as the team wants the project to participate in an entrepreneurship contest in nearby Hengqin for more funding. “We will receive a lot of data from the satellites,” she explains, “which could be processed and handled by AI [artificial intelligence] to develop different types of data products for the purposes of navigation and

other [applications].”

Launch date

When it comes to Macao Science 1, one big question remains: when will it take to the skies? The launch date, however, is yet to be finalised. In 2018, the proposal was made and the naming process was undertaken last year, with more than 1,100 people from the city submitting more than 1,500 possible names for the satellite over the period of a month. Finally, the name Macao Science 1 was chosen. The city’s first satellite was originally slated for launching from the Mainland some time next year. However, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has already hit the global economy hard so delays to the project might be expected.

“Concerning the progress of the satellite, we are now in the stage of design and signing relevant contracts,” says Prof Zhang. “I was 100 per cent sure it would be launched by the end of next year but that’s difficult to say now with the COVID-19 outbreak.” However, the works for the satellite, data centre, ground station and upgrade of the SKLplanets facilities will continue on regardless, according to the professor. “There have been different types of challenges for the project due to its complexity,” he says, “and this has required technical and administrative co-operation between all the involved parties. But, so far, I’ve not encountered any challenges that we can’t overcome. This project is highly regarded by the management of MUST, as well as fully supported by the SAR’s government.”

It’s safe to say that Prof Zhang is extremely upbeat about the prospect of developing satellites in Macao. “I hope,” he concludes, “when you come again to interview me in four or five years’ time, your phone will be using the data from our satellites.” With the unswerving support of the local and central governments, as well as the total commitment from experts in the field locally, nationally and globally, not to mention SKLplanets itself, Prof Zhang’s vision may soon become a reality. But he does bring us back down to Earth at the end of our interview, saying simply: “There is still a long way to go.”

Otherworldy experiences

SKLplanets at MUST has only been going for less than two years. But over this time, it has nevertheless been involved in much more than just the satellite project. “Our laboratory is still growing,” says Prof Zhang, “and we hope it will become a more efficient research institution.” According to the SKLplanets director, the laboratory has already been involved in the research and development of the nation’s first robotic mission to Mars, which is expected to send an orbiter, lander and rover to the Red Planet later this year. “The data collected and compiled during this mission will also be sent to our laboratory for analysis,” he says, “so that we can understand more about the structure, atmospheric conditions and other [aspects] of Mars.”

Mars is not the only planet in the solar system the CNSA has its eyes on. The administration also plans to launch a Jupiter explorer in the future – and that’s a mission that will see SKLplanets assisting in the research and development process, according to Prof Zhang. Since 2005, MUST has been involved in the Chinese Lunar Exploration Programme, which is an ongoing series of robotic Moon missions. Prof Zhang notes that his team will further help in the programme by studying some of the soil samples that are collected by Chang’e 5, a robotic lunar exploration which is scheduled for launch later this year. “We will carry out analysis on the soil samples from the Moon with our advanced equipment,” he says, “to shed more light on the Moon from its origin to its evolution.”

SKLplanets boasts five labs and centres in the areas of astrophysics and astrochemistry, small body physics, planetary environment simulation, high performance computing and science communications. Prof Zhang notes that his team is also working on setting up a new astrobiology lab which will see more studies done on one of the planet’s greatest unsolved mysteries: the origin of life.