It’s no secret that Macao is a fast-evolving city. Less than 20 years ago, for instance, one of its most visited areas – the 5.2-square-kilometre Cotai – didn’t even exist. Nor did any of its towering integrated resorts. But with development comes casualties. A lot of structures that generations of Macao people grew up taking for granted have vanished. The Macau Power Station in Areia Preta. Taipa’s landmark cotton mill, with its distinctive sawtooth roof. The iconic seafront Hotel Caravela, on Avenida da República.

Conservation is becoming more and more important to the city. Fortunately, a sizable swathe of Macao Peninsula’s historic architecture is protected by its UNESCO World Heritage status. But what about the structures that are already lost, and all the memories associated with them?

This is the question Macao’s creatives and curators are working hard to answer. In different ways, these people are the city’s self-appointed history keepers.

Ho Tai On: bearing witness

Over seven decades, the antique shop owner Ho Tai On has watched his hometown transform from sleepy fishing village into a vibrant resort city. In 2005, he felt compelled to start documenting the city’s changing face.

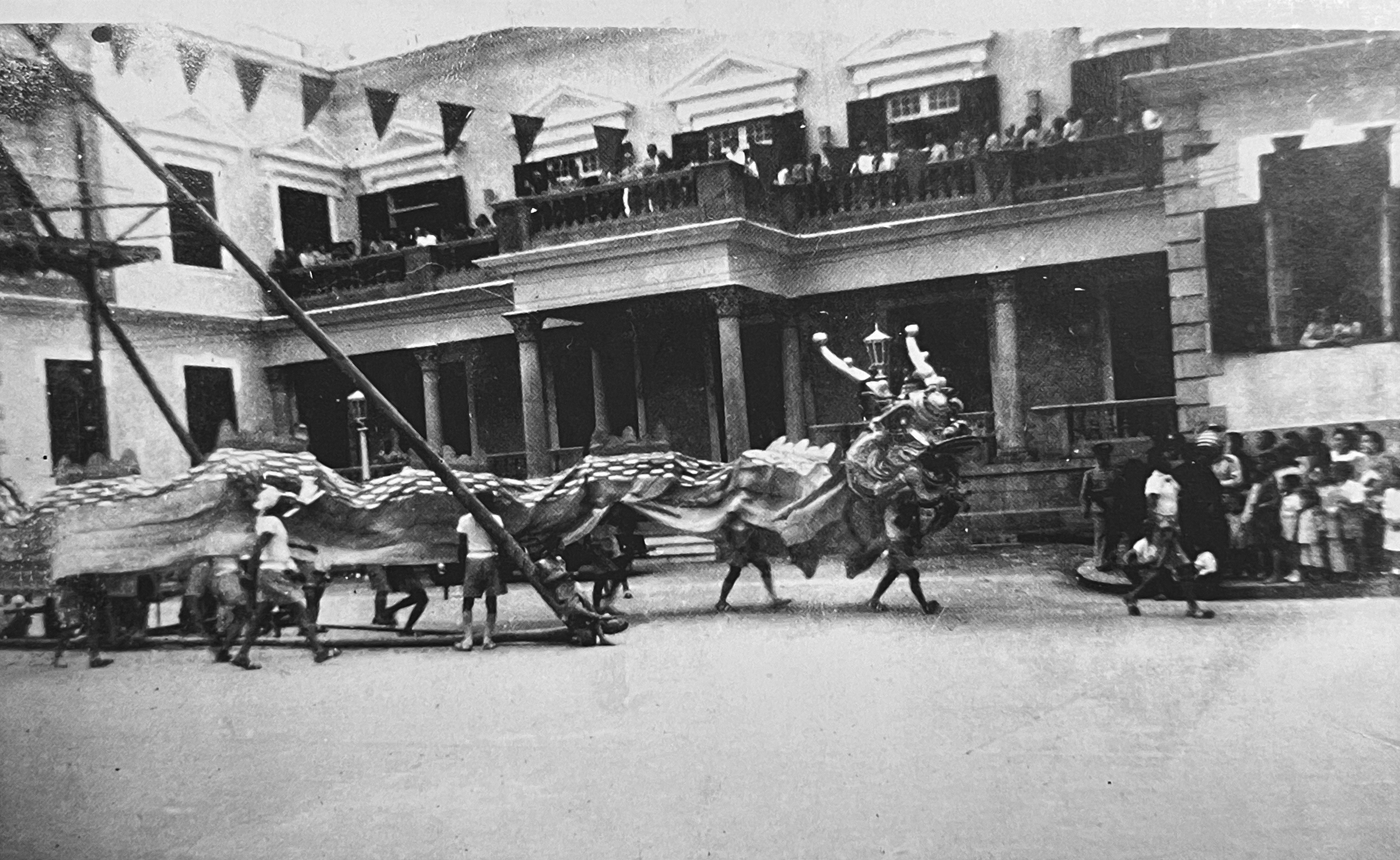

Ho does this through turning old photographs of Macao into postcard series and books. The 73-year-old’s first book, The Past and Present of the Inner Harbour, was published in 2007. Sponsored by the Cultural Affairs Bureau, the book is a guide to historical trails around what was once the city’s fabled main port.

Over the years, Ho has broadened his postcard project to include black and white photos he takes himself using his Canon cameras. “I use black and white to give a sense of ancientness,” he says. “Because the pictures I take now, in the future, will be considered the past.”

Ho sells the postcards at his own small shop, Fu Kei, in Beco dos Faitiões in the Inner Harbour – along with antiques and vintage Macao memorabilia. Each set of postcards is more than a simple record of what’s been lost. Rather, the images depict how changes throughout history have shaped 2023 Macao.

Nam Van Lake, the Macau Grand Prix, local schools, and the now-defunct Yat Yuen Canidrome have their own sets. So does the Workers’ Stadium, which used to be where the Grand Lisboa is today. It’s been relocated near the Macao-Zhuhai Border Gate.

Many subjects of Ho’s postcards have disappeared completely. The rose-coloured Hotel Caravela started off as prominent Macanese businessman Bernardino de Senna Fernandes’ personal home, then got converted into a popular hotel in the 1950s. It was demolished in 1979.

“Photography makes it easy to understand history through visualisation,” Ho says. “If you are a local here, having lived and grown up here, there is no reason to not know and explore the history and the culture behind this city.” He likes to think both locals and tourists can use his work to explore Macao’s streets and their storied context.

YiiMa: an artistic interpretation of the past

YiiMa is the collective name of a local artistic duo, Ung Vai Meng and Chan Hin Io. Both share Ho’s view that people in Macao should know the city’s past.

The pair have collaborated for years to create art in the form of photography, videos, sculptures, literature and performance art pieces – all depicting missing links between Macao’s past, present and future. YiiMa means ‘the twins’ in Mandarin and refers to how close the two men have grown as they’ve worked alongside each other.

Sixty-five-year-old Ung is a Macao-born painter and conceptual artist who’s held high-level roles at the Macao Museum of Art (MAM) and the Cultural Affairs Bureau. Chan is a photographer who was born in Zhongshan, in the mainland, in 1964, and moved to Macao in the ‘90s. He’s always been interested in photography, and became passionate about documenting his adopted home’s evolution with his camera.

Since 2009, Chan has published more than 10 photography books on Macao. He’s also held solo exhibitions in Australia and Europe. His photos can be found at MAM, the Macao Foundation, the Archives of Macao and Lisbon’s Belém Culture Centre.

The men’s work was featured at the 2022 Venice Biennale, in Italy, and is currently on display at the Tap Seac Gallery in Tap Seac Square. That exhibition, titled “Allegory of Dreams: On the Way to the International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia” will be at Tap Seac until 21 May and offers a glimpse of Macao’s hidden corners and fading memories.

One photo from the project shows an alley near the YiiMa art studio. In the 19th century, this was a market for human labourers – Chinese people who were shipped off to various parts of the world to dig for gold. “These people imagined there’d be, like, a mountain of gold,” says Ung. “When they got to those places, their working conditions were not as they imagined. They were treated cruelly and many of them even died.”

Macao’s labour trade lasted until 1874. Destinations included San Francisco and Los Angeles in the United States, as well as Melbourne in Australia.

Another part of Ung and Chan’s project involved photographing the interiors of local family’s homes. “We chose different families and studied their stories,” Ung explains. “So, through the exhibitions, people can understand what happened in Macao.”

Lúcia Lemos: Macao needs memory storage

Those structural losers are one reason Creative Macau founder Lúcia Lemos believes the city needs more dedicated places preserving Macao’s unique history. “Many people want to know the history of Macao, and it’s a city that thinks memories are important – so we need to have places to keep those memories,” the 68-year-old says. “Museums work as a storage for our memories. As more and more things disappear over time, our memories will fade. No memory means no history.”

Macao already has several good museums and exhibition venues, of course, including the newly opened Iec Long Firecracker Factory. The Cultural Affairs Bureau has transformed the long-abandoned industrial site into a museum showcasing one of Macao’s major industries of the 20th century.

There’s also the Macao Museum, near the Ruins of St Paul’s, offering many views of Macao’s history. But Lemos wants more. “For example, we should have a museum of photography that can store old photographs of Macao,” she says.

Lemos moved to Macao from Portugal in 1982, with her Macanese husband and baby daughter. The city was not as metropolitan as it is today. It was occupied mostly by the Chinese, Portuguese and Macanese, as well as some Filipinos – and people lived in small flats as opposed to the big residential buildings you see everywhere now. “We could hear conversations and the neighbours shouting from the other apartments,” Lemos recalls.

Creative Macau is a non-profit organisation helping creative industries become sustainable. Its current office is in the Macao Cultural Centre, in NAPE. When Lemos moved to Macao, the neighbourhood had not been built – it was an empty expanse of reclaimed land used for fairs and special events.

Lemos is now a mother to three adults and, in a way, the city grew alongside her family. She describes the process behind this growth as a “chaotic mess” that’s resulted in something great. Living conditions in Macao have improved as its economy has grown. Locals can afford to buy property and send their children to schools abroad.

“As people travel more, they become more open to working with others and less afraid of new things,” Lemos says. After 1999, there were more subsidies available for children, the elderly, health, education, and the arts. “The government nowadays gives millions to art and cultural projects. They didn’t have that kind of money before,” Lemos underlines.

Ho, Lemos, Chan and Ung all agree that Macao’s history must be cherished, and feel – in their own ways – a responsibility to get the past chronicled for younger generations.

“The past is an experience and we can learn a lot from it,” says Ung. “We try to reconstruct those memories. Even if the actual memories don’t exist anymore, at least they exist in images.”