In the southeast of the Cabo Verde archipelago, on the island of Boa Vista, lies a tropical paradise. White sand, turquoise water, and warm, West African sunshine. This is Ervatão beach, a few hundred kilometres off the coast of Senegal. Not only a holiday destination for humans, thousands of sea turtles make an annual pilgrimage to these shores – as their ancestors have done for millennia.

Between July and September each year, more than 3,000 of the dinosaur-era reptiles emerge from the ocean to lay their eggs at Ervatão. It is one of the world’s three biggest sea turtle nesting sites, along with the US state of Florida, and Oman.

A sea turtle’s nesting ritual lasts about two hours, and happens in the relative cool of night. Female turtles, some weighing up to 150 kg, heave themselves out of the water to seek dry sand for their nest. Using only their hind legs, they dig the holes in which they’ll deposit up to 80 eggs. Each turtle repeats this process between two to eight times during nesting season. Then, maternal duties complete, she’ll return to her unencumbered life in the coastal waters of West Africa.

Of the six species of sea turtles that live in the Atlantic Ocean, five are found in Cabo Verde. Green turtles are known locally as “pardas”; raised-hull turtles; olive ridley turtles; leatherback turtles; and, the most common at Ervatão, loggerhead turtles. Collectively, these species made about 200,000 nests across Cabo Verdean beaches in 2020 – a dramatic increase since 2015, when just 11,000 nests were counted.

Portuguese sailors visiting the islands in the 15th century mentioned an abundance of turtles in their logbooks. So did Charles Darwin. Cabo Verde was his first stop after setting sail from England on the Beagle. Darwin spent about three weeks on the island, before heading for Brazil.

The turtles he saw in 1831 were most likely forebears of the latest batch of babies – who will return in about 20 years’ time, to lay eggs of their own. It’s turtle tradition to return to the beach where they themselves hatched, to bring forth the next generation. This is hardwired into their DNA.

When you see the thousands of tiny hatchlings racing towards the sea during summer (mainly August) in Cabo Verde, it’s easy to forget that these creatures are at risk of extinction. But speak to some of the older Ervatão beach locals, and they’ll describe nights where the sand itself appeared to be shifting, there were that many baby turtles on the move.

Their odds aren’t great, however. Only about two out of 1,000 sea turtle hatchlings live to reach breeding age (the ones that make it can live on beyond 100 years of age).

The first problem is that sea turtles have many predators. Their eggs are a treat for ghost crabs and birds, stray dogs and feral cats, and even humans. People have hunted sea turtles for thousands of years. While they are now globally protected, sea turtles still attract poachers and are part of the multi-billion-dollar market for illegally traded wildlife.

Sea turtles’ beautiful shells remain sought-after for decorative purposes, while their eggs and meat are considered delicacies. Certain cultures in Asia even believe sea turtle products have aphrodisiac properties, though there is no scientific evidence for this. Where there’s demand, there’s supply. Poorer inhabitants of Cabo Verde can be tempted to hunt and sell sea turtles to make money. Local scientists see poaching as a serious threat to the species.

Another major reason behind its endangered status is habitat loss. At Ervatão, for example, hotels and resorts springing up along the shoreline – as well as thousands of tourists, mainly from Europe – have hijacked sea turtles’ ancestral nesting grounds over the past few decades.

Tourism is the biggest money maker in Cabo Verde, a developing Portuguese-speaking country of about 600,000 people. While construction projects that help the country meet tourism demand aid Cabo Verde’s struggling economy, they’re terrible for sea turtles. Not only is there less space and more hazards, but heavy machinery compacts the sand and soil – making it impossible for turtles to dig holes. Bright, electric lights from buildings also deter the lumbering reptiles, who prefer digging nests by starlight alone.

All this development means Ervatão’s sea turtles have been relegated to isolated and inhospitable pockets of coastline, when they used to have vast stretches of sand to themselves.

Local efforts revive sea turtle populations

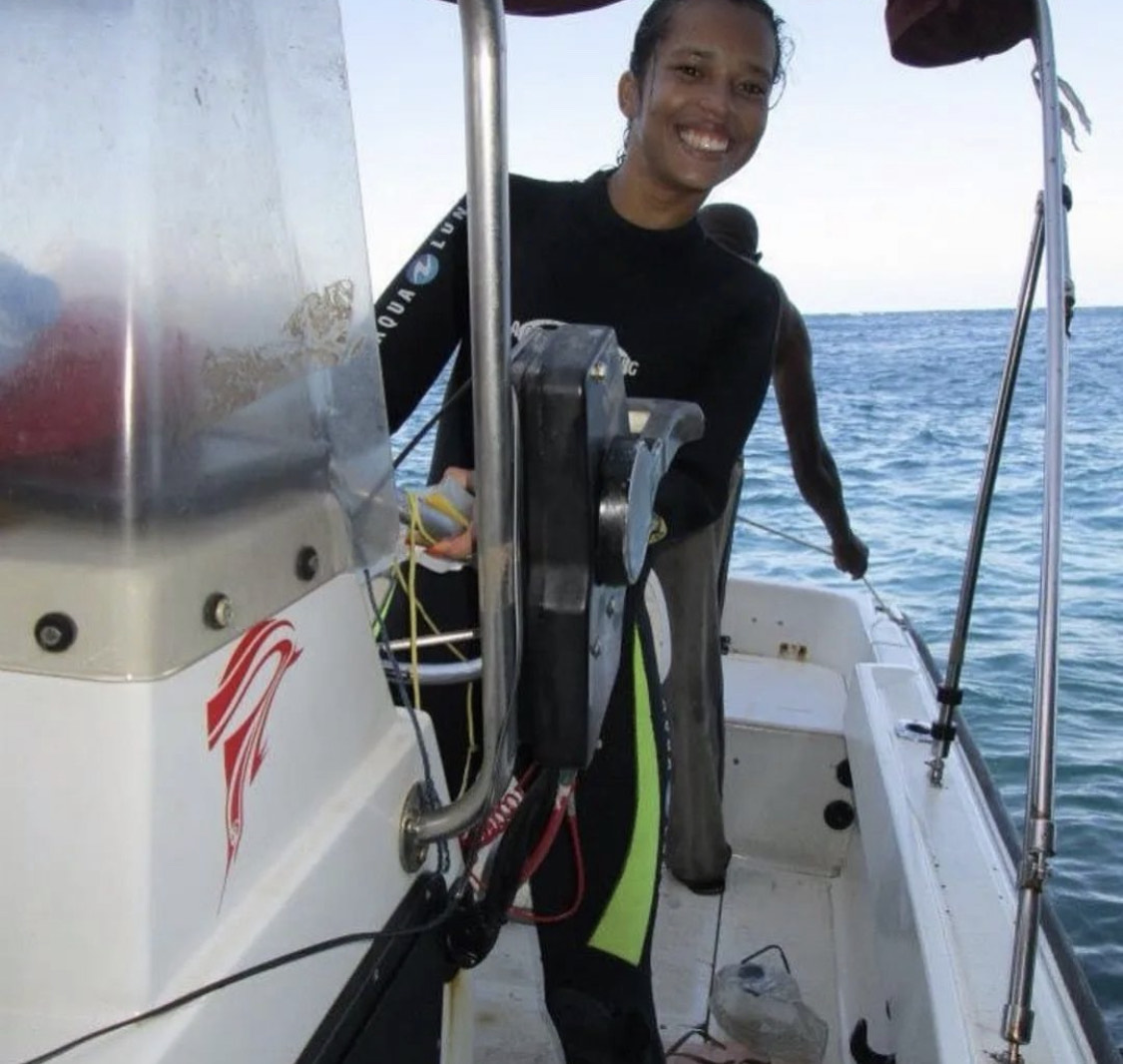

Not all human activity harms sea turtles, however. Local NGOs on all 10 of the country’s islands are doing everything they can to protect the precious species – efforts illustrated by the increasing numbers of nests. Biologist Patrícia Rocha, vice-president of an NGO called Biosfera, says awareness campaigns have made the country care more about wildlife conservation.

Some hotel operators are beginning to add red filters to their dazzling white lights, for example. They’re choosing to hold off hosting noisy activities at night, so as not to frighten turtle mums-to-be and hatchlings.

According to Rocha, the biggest boost to Cabo Verde’s sea turtle population has been diligent surveillance carried out by NGO workers. They, including Rocha herself, take it upon themselves to patrol beaches like Ervatão – and it’s led to a significant drop in poaching.

Rocha is proud of these developments: “There is a greater environmental awareness in our country”, she says.

Cabo Verde’s government has been developing legislation to protect sea turtles since the early 1990s. It also established the National Directorate for the Environment to coordinate civil society efforts to preserve sea turtle populations.

From a policy perspective, Rocha says the right laws are now in place. It’s illegal to possess, consume, or trade individual sea turtles, their meat and their eggs, for example. Laws also penalise the degradation or transformation of sea turtles’ natural habitat, as well as disturbances during their nesting season.

Nevertheless, Rocha says these laws “need to be put into practice with greater responsibility.” For example, to feed its building boom, there are Cabo Verdean companies harvesting sand from the country’s beaches to make concrete – which flouts legislation. There are communication gaps and not all authorities are on the same page when it comes to protecting turtles, Rocha notes.

“Despite some illegal capture of turtles, on land and at sea, our biggest concern has to do with the unbridled collection of sand on the nesting beaches – it is a problem that we have to solve.”

Another major, even more difficult problem is global warning. Warmer temperatures result in more female hatchlings, which Rocha explains leads to an off-kilter gender ratio that’s bad for breeding. She says that males stop developing at around 30 degrees Celsius, and that a spate of unusually hot summers have exceeded this temperature.

Humans and turtles, helping each other

Rocha believes that humans and turtles both have a place in Cabo Verde, and that the two often-at-odds populations can help each other. “It’s not that I put turtles in a prominent place, to the detriment of people,” she says. “But balance is key, as is having people on board with our conservation efforts.”

She points to the fact that sea turtles have become somewhat of a symbol of Cabo Verde. There are tour operators offering turtle watching excursions and many tourists visit specifically for this experience. When they cast around for souvenirs, there are sea turtle wood carvings, sea turtle t-shirts, and sea turtle fridge magnets galore. The perfect keepsake from a Cabo Verdean beach holiday.

Rocha says the challenge now is to keep turtles coming back, along with the tourists.