TEXT Richard Lee

We all know about Macao’s ‘tangible’ heritage – its physical historical remains like the Ruins of St Paul’s. But what about its ‘intangible’ heritage – old stories, traditions and customs? Every year, the city is doing more to protect and promote this ‘unseen’ history.

Macao’s heritage has been forming for more than 450 years. Since 1557, when Portugal was granted the territory by China as a trading post, the city has created its own unique and fascinating history – one modelled by heavy Chinese and Portuguese influences, as well as influences from many countries and cultures in between.

For years, locals and tourists alike have been able to admire relics from the past like the Ruins of St Paul’s, the Guia Lighthouse and some of the oldest temples for miles around, such as the A-Ma Temple in São Lourenço, which was built in 1488 and proves that Macao’s heritage stretches back even beyond the past 450 years. These monuments to a bygone era still colour the city, attracting throngs of tourists and creating a metropolis that mixes its modern adeptly with its uniquely historical.

Nowadays, the stucco-clad walls of the Fortaleza do Monte – Mount Fortress, which stands above the Ruins of St Paul’s and houses the Macao Museum – that once dominated the surrounding land are a main focus of the ‘Historic Centre of Macao’, one of the most important UNESCO World Heritage sites of its type. The Historic Centre was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2005 and covers culturally and historically important sites like the Moorish Barracks, Senado Square and St Joseph’s Seminary and Church.

It is difficult to understand the city’s past or present without taking the Catholic heritage into account, especially given the heavy involvement of Catholic churches in charitable organisations.

But all that is what you can see. It’s Macao’s ‘tangible’ heritage. What’s equally important is all the history you can’t see – the ‘intangible’ heritage. The stories, the traditions, the beliefs and the customs. And now there is special attention in the SAR on this side of heritage, which also attracts tourists and reminds locals about the territory’s past. This is the untouchable history of Macao that the government, among other bodies, is keen to preserve.

Not all heritage is created equal

Mariana Pereira is an expert on heritage and archaeology. She is a PhD researcher at the UK’s Cambridge University but she knows Macao and its history extremely well and has previously worked in the city’s heritage sector. Pereira says that the city’s heritage management framework is based on UNESCO’s recognition of the two types of cultural heritage – ‘tangible’ and ‘intangible’. She says that most people are familiar with what UNESCO terms as ‘tangible’ heritage – the physical remains of history, whether historic buildings or objects.

However, for Dr Priscilla Roberts, the associate professor at the City University of Macau’s Faculty of Business – who also doubles as a specialist on Asian history, previously holding the title of associate professor of history at the University of Hong Kong – Macao’s tangible heritage isn’t just about the main buildings that make up UNESCO’s list. Its tangible heritage includes all the ‘temples, churches, houses, shops, forts, tiles on street signs, mosaics, tiny Chinese shrines, the Leal Senado building and its associated library, lighthouses, administrative buildings and pawn shops’.

Macao’s tangible heritage is protected by the Cultural Heritage Protection Law (No 11/2013) which the government’s Department of Cultural Heritage is responsible for enforcing. However, Article 71 of this law also defines what intangible heritage should be protected. Under Article 71, intangible heritage includes oral traditions, artistic expressions, religious practices and events and practices related to nature and traditional crafts. What actual examples fall within these broad areas, though, is decided through 30-day public consultations conducted under Article 79 of the law – and the list is always subject to change. As of the last public consultation, just last year, bamboo scaffolding, as well as beliefs and customs associated with two Chinese folk deities, Tou Tei and Chu Tai Sin, have now come and gone from the list. But many important examples of intangible heritage have stayed the course…

Religion and faith

It is estimated that, out of a population which is creeping towards the 680,000 mark, there are about 30,000 Catholics living in Macao. For them, the rich Catholic history of the city is of huge importance – as it is to the throngs of Catholic tourists who visit the territory every year. There are also more than 8,000 Protestants residing in the city. It is – as Dr Roberts notes – ‘difficult to understand the city’s past or present without taking the Catholic heritage into account, especially given the heavy involvement of Catholic churches in charitable organisations’.

The Portuguese brought a strong Catholic presence into Macao as early as the 16th century. The city became home to Catholic missionaries and, over time, the churches and cathedrals that have come to dominate the cityscape were built. Since the 18th century the proportion of Catholics in the city has been declining but that does not mean its heritage should not be protected, whether tangible or intangible.

One such example of Catholic intangible heritage is the religious procession. There are multiple processions throughout the calendar, including the annual Procession of Our Lady of Fátima, which takes place on 13 May every year. Macao’s Catholic population can be seen swaying into the dark night through a sea of glimmering electronic candles and phone screens during the procession. A small white figure with hands clasped in prayer is carried and she snakes her way above thick crowds of people in a magnificent spectacle.

The small white figure is a statue of the Virgin Mary and the procession winds its way from St Dominic’s Church, through the Nam Van and Sai Van areas, and finishes at the Chapel of Our Lady of Penha, at the top of Penha Hill, where a solemn religious ceremony is held. The event recalls the apparitions of the Virgin Mary to three shepherd children in 1917 in the central Portuguese town of Fátima. The appearance of Our Lady at Fatima culminated in, later that year, also in Fátima, the ‘Miracle of the Sun’, when the sun was said to have danced and changed colours in front of a crowd of more than 30,000 people. It was a moment which validated the faith of many Catholics.

The Procession of Our Lady of Fátima has a similar effect every year in modern Macao as it binds Catholic Macao residents with, as Pereira explains, immigrants and visitors, such as people from the Philippines who, united in faith, also carry the colourful tradition into the night. In all, Macao’s Catholic processions are, as Dr Roberts muses, the modern ‘expressions of deeply felt religious beliefs’.

Beliefs and traditions can disappear or fade away slowly in the modern world.

Traditional Chinese cultural and religious beliefs are just as important when it comes to Macao’s heritage. Na Tcha Temple, built in 1888, is a Chinese folk religion temple in St Anthony’s Parish – the first of two Na Tcha Temples in the city – dedicated to the worship of the deity Na Tcha. The chairman of the Na Tcha Temple Association is Ip Tat and he says that after the transfer of administration from Portugal to China took place in 1999, ‘more and more festivals were protected’ and ‘Macao citizens started to pay more attention to all kinds of culture, including traditional Chinese beliefs’. In modern Macao, Ip muses that ‘Chinese faith is integral to the city’ and that ‘there are a lot of travellers who go to Macao just to visit the temples and churches’. For Dr Roberts, this belief can be seen ‘in terms of daily observances, small shrines and offerings to the gods’ across the city.

For Ip, who grew up going to Macao’s temples, ‘they are not just about belief’. He says that the temples create the communities that organise traditional and social events, for instance. He says: “It is all about going to temples for meals, chatting and watching Chinese opera.” One such major annual traditional and social event happens on the eighth day of the fourth lunar month – the Festival of the Drunken Dragon. It begins at the Kuan Tai Temple near Senado Square, where men perform a drunken dance with the wooden head and tail of a dragon which is showered in liquor and sparkles in the sun as the streets erupt with the shrill rhythmic clang of gongs and the dull beat of drums. They then parade through Macao to the Inner Harbour and drink alcohol until they drop.

The origin of the festival, as Ip notes, are uncertain. It is likely that the tradition originated in China for, as Dr Roberts says, ‘Macao is also part of southern China – it’s not surprising if its heritage is closely related to the region’. Some believe the festival has its legendary origins in Guangdong’s old Xiangshan county, which was renamed the county of Zhongshan around 100 years ago. One story tells of a dragon that was struck dead by a man who had been given courage by alcohol. The beast lunged from a river at a collection of villagers who were pleading to a statue of Buddha to be cured of a great plague. On drinking the river water, reddened with the dragon’s blood, the villagers found themselves cured of the disease.

Subsequently, it is believed, the Festival of the Drunken Dragon was established to ward off plague. As it spread to Macao, reckons Ip, it grew from the preserve of the city’s fishmongers and soon became a major cultural event. Today, says Ip, the festival begins with fishmongers gathering on the eve of the procession to eat a ‘dragon boat longevity meal’ together. On the morning of the procession, as the dance begins, ‘dragon boat longevity rice’ – rice that brings peace and prosperity to the tens of thousands of people who consume it – is distributed outside Kuan Tai Temple. The rice, the dance, the atmosphere and the crowds – it all makes for a unique Macao experience, one that is also protected as a great example of the intangible heritage on show in the city.

Food and drink

Some would say food is a religion in itself – however, as a protected item of intangible heritage in Macao, it is in a completely separate category to faith. It is held, though, in equally high regard as one of the city’s most important examples of intangible heritage due to its unique background and taste. Macao has enjoyed nearly five centuries of culinary history, which, as Pereira notes, has been constructed from the many different cultures that have passed through the city. As the Portuguese moved to Macao, so too did their ingredients – the spiced pork and pepper chouriço sausage, olives, dried salted cod and many other foods, all of which can still be found in and around the city. Portuguese dishes were also imported, like clams in white wine and ‘arroz de marisco’, or seafood rice, and they serve as the bedrock of Macanese cuisine. Both of these dishes are still served at restaurants like Portuguese establishment A Lorcha, near the A-Ma Temple.

Pereira explains that as Portugal grew as a trading empire, so too did its access to new ingredients. Cinnamon, saffron, pepper, chilli and cloves all travelled across the world with the Portuguese, many of these spices ending up in Macao as did the different recipes and cooking methods from across the Portuguese territories. It is probable, though debated, that African chicken, still a popular dish in Macao, originated in the Portuguese territories in Africa before it was brought to Macao. The dish personifies the culinary fusion that makes up Macanese cuisine – the pepper hails from Portugal, the peanuts from Africa, the spice from China and the coconut from India, with the cooking techniques learned from those lands.

Macanese gastronomy is primarily based on cooking methods from Portugal but it incorporates styles and ingredients from Africa, India, Malaysia, China and other places across the globe. It takes some of the best of each and was allowed to develop over time in an independent and unique manner. Pereira says that Asian foods really helped to shape its style, especially ingredients like Malaysian coconut milk, Indian spices, Southeast Asian ginger and tumeric, as well as the introduction of curry. Chinese ingredients were, of course, of prime importance to shaping the cuisine, as was the introduction of Yue cuisine, the culinary style of Guangdong province. Macanese gastronomy survives today and is repeatedly promoted and supported by the government as an important part of the city’s heritage.

What marks Macanese gastronomy as unique, explains Pereira, is not actually the abundance of different cuisines but how they interact with each other. She says that, as the Portuguese settled in Macao, they married people from all over Asia and beyond – from places like Japan, India, Malaysia, Africa and China. As families became ethnically mixed, so did their food. Different culinary traditions began to merge to create new dishes. Portuguese dishes were changed to use local ingredients in place of imported ingredients that were hard to find at a particular time in the city.

Over the years, the unique and eclectic Macanese cuisine developed, including the British-inspired ground meat dish of minchi, which is beautifully flavoured with molasses and soy sauce. Then there’s stir-fried curry crab, pork chop buns, egg tarts and ‘pato de cabidela’, a stew made by cooking duck in red wine and its own blood. For Pereira, the nature of Macao as a trading hub has created a food that exists nowhere else in the world. She says that it’s this unique fusion of cuisines from around the world – which, for a few patacas, anyone can experience – that led to UNESCO, just over two years ago, to recognise Macao as a Creative City of Gastronomy, an honour that also helps to protect and promote this deliciously intangible piece of Macao’s heritage.

Art and soul

In the serene gloom of a small Macao theatre lies a black stage on which a puddle of light illuminates a painted wall and a couple of haphazard chairs. A handful of players gesture excitedly as they strut back and forth across the space, acting out their stories for the expectant audience. As the crowd intently listens, they hear the players speak in a language that sounds like a mish-mash of Cantonese, Portuguese and English. Welcome to one of the Macao theatres that stages traditional plays and welcome to a dialogue that is not made up of three languages at all – these actors are speaking Patuá, the traditional language of Macao.

As Pereira explains, Patuá initially developed among the descendants of mixed Portuguese and Asian families in Macao in the 16th century. It was once widely spoken and evolved as other languages do, merging words from lands like India and Malaysia into the Portuguese and local Cantonese hybrid language. By the 19th century, however, Cantonese was much more widely spoken in Macao, as was English, which was entering the city from Hong Kong. What was once the language of trade in the city was, by the 1950s and 60s, as Pereira puts it, ‘no longer considered to be Portuguese proper’. Today, only a handful of people speak the language in Macao – UNESCO, over the past few years, has even estimated as few as 50 people speak it, deeming it a critically endangered language in the process.

Pereira says that ‘modern Patuá differs in many ways to past Patuá’ due to the natural evolution of the language and the fact that it is now only used by a small number of people and doesn’t serve the important cultural role that it once did. “The people in Macao no longer use it to communicate,” she says. “It’s also no longer used in schools. But if people don’t think the language is important any more then we can’t make communities speak it if they don’t want to. But we can record it in a register if people, one day, want to go back to it and learn it. It would be so sad if it disappeared, though. Every language is a way of perceiving the world so a world view is gone when a language fades away.”

The language of Patuá is not recognised as an item of intangible heritage in Macao – but the art of Patuá theatre features prominently on the list. Since the 1930s, Patuá theatre has regularly passed satirical judgement on the shifting politics and social movements of the city as well as providing an animating or moving show for local theatre-goers. In recent years, theatrical company Dóci Papiaçam di Macao, which was founded in 1993, performs annually at May’s Macao Arts Festival using Patuá language performances to lightheartedly mock local traditions and events and, of course, to entertain. Pereira says these performances showcase the language, noting that they act as a focus for the community and experts alike to consider how Patuá should be safeguarded for future generations.

Macanese lawyer Henrique Miguel Rodrigues de Senna Fernandes is a playwright and director of Dóci Papiaçam di Macao. He says: “Patuá theatre gives diversity to the cultural panorama of the SAR. It reflects the multiculturalism which is the essence of Macao and that’s the concept the SAR cherishes and embraces. Through Patuá theatre, the audience can experience an environment where the context is neither Chinese nor Portuguese as it’s in a language that is genuinely from Macao.” The director says that Patuá theatre is a Western-style theatre that ‘relies highly on the language’ and ‘reflects the voice of the anonymous common citizen’ but there are always comedic elements like slapstick and satire. He says that Macao’s intangible heritage, including Patuá theatre, ‘tells how unique this tiny little city is from the rest of China’. “Heritage is a way to promote our sense of belonging,” he concludes. “In the age of globalisation, being different should always be cherished.”

Safeguarding the future

As Macao continues to evolve as a city, its tangible heritage will likewise change. Much tangible heritage already survives but, as Pereira notes, although ‘we safeguard older buildings’ with good examples of reuse such as Mount Fortress, with Macao Museum nestled within its walls, ‘some buildings are demolished’. “This is to do with the values we give to them,” she says. Ip adds: “The government does a very good job in protecting Macao’s heritage, however it should be everyone’s obligation to protect heritage. It isn’t much help if people just rely on several organisations and the government.”

Yet tangible heritage is only part of what makes Macao such a unique historical city. Even a cursory glance at some of Macao’s intangible heritage items shows how the city’s complex past is alive and well, even if you can’t ‘see’ many of the elements that make it up. But Pereira warns that even when items of intangible heritage are safeguarded, like in Macao, they can be ‘frozen or commercialised’, accruing stakeholders who could make protection complicated and traditions inauthentic. Moreover, as Ip laments, not all intangible heritage survives. “Beliefs and traditions can disappear or fade away slowly in the modern world,” he says.

As Macao puts greater emphasis on heritage tourism, intangible and tangible heritage are becoming intertwined. For example, when a temple is preserved, so are the festivals and traditions of the communities who use that building. Perhaps the sky-high bamboo scaffolds that cradle every Macanese construction sum it all up perfectly. Bamboo scaffolding is no longer present on the intangible heritage list because, some would say, it is not a remnant of Macao’s past. It is a living tradition that survives within the modern cityscape. This fusion of intangible and tangible heritage gives Macao a heritage to celebrate long into the future.

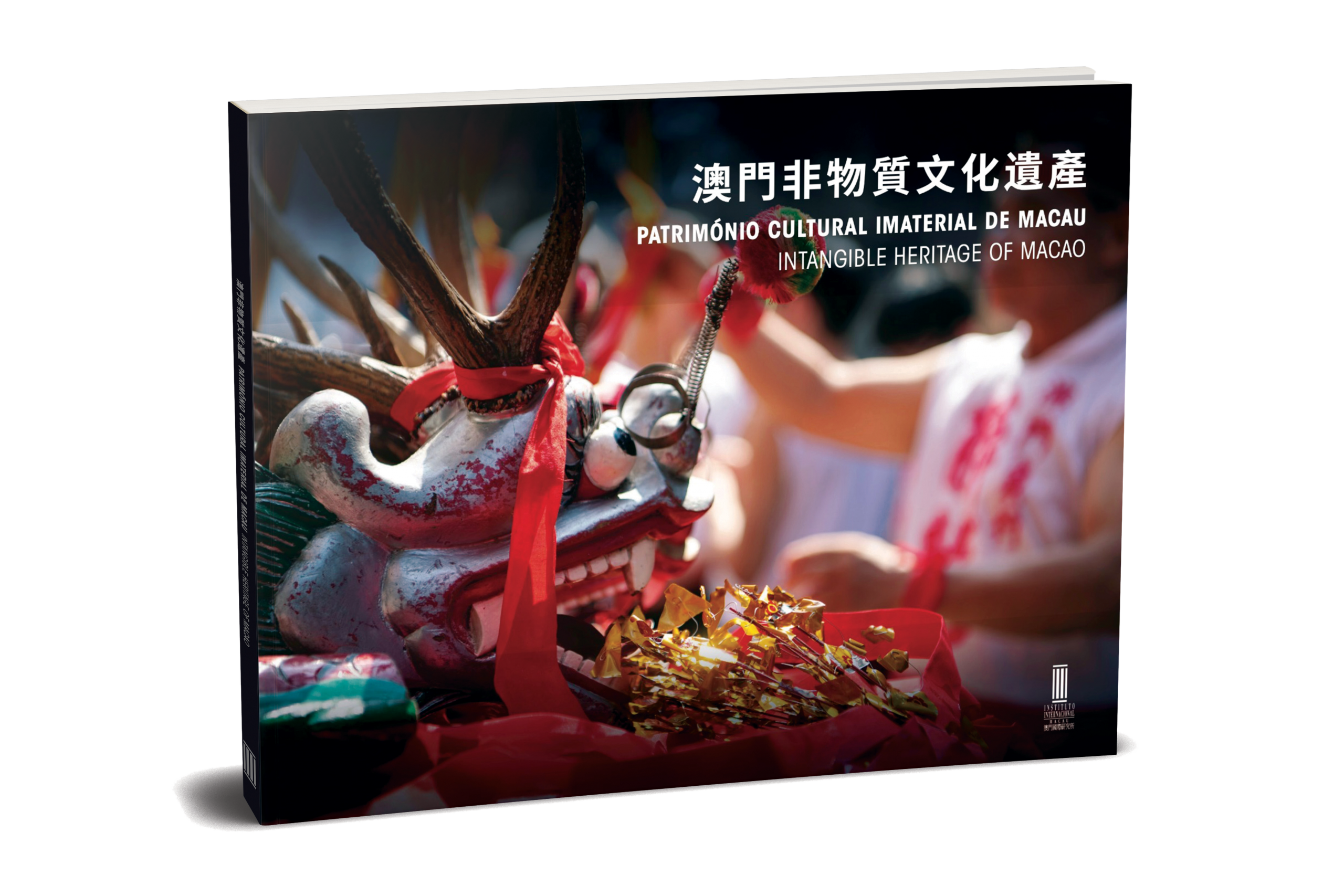

To help document Macao’s intangible heritage, the International Institute of Macau published a book on all 12 elements just last year. The trilingual book gives an introduction to each element coupled with an array of beautiful photography. It’s available on bit.ly/2uWCf5x.

Macao’s list of intangible heritage

The 12 items on the current list represent Macao’s unique past

The belief and customs of A-Ma

The traditional customs and beliefs that surround the patron goddess of fishermen, A-Ma, date back hundreds of years. According to legend, Macao may have drawn its name from her.

The belief and customs of Na Tcha

The beliefs and customs that surround the Na Tcha date back 300 years in Macao. The child-like god is believed to drive away demons and disasters and, according to legend, used to play on Mount Fortress.

Cantonese Naamyam

Cantonese Naamyam are stories, narrated and sung by the blind. In the 1950s, this art was popular in Macao, with stories performed regularly on the radio.

The Festival of the Drunken Dragon

The yearly Festival of the Drunken Dragon is traditionally celebrated by local fishmongers to bring prosperity in the coming year.

Herbal tea brewing

Brewed from traditional Chinese herbs in southern China, herbal tea has been used to prevent disease for centuries. Macao is known for its brewing and it exports herbal tea across the world.

Macanese gastronomy

For more than 400 years different ingredients and recipes entered Macao from Portugal,

China and across the world. As these ingredients and recipes combined, it produced the unique Macanese cuisine.

Patuá theatre

Patuá is a traditional Macanese language. Special theatrical performances are a great way to keep it alive.

The Procession of Our Lady of Fátima

The procession falls annually on 13 May, commemorating the supposed miraculous appearances of the Virgin Mary to three children in Portugal in 1917.

The Procession of the Passion of Our Lord, the God Jesus

Every Lent, this two-day procession, which dates back to 1708, takes place in Macao’s streets. It follows the form of the ‘Way of the Cross’, recalling the experiences of the passion and death of Jesus as depicted in the Bible.

Religious wooden figure carving

For more than a century, the art of carving sacred images in wood, such as depictions of Buddha, have been handed down from generation to generation in Macao. This skill survives today.

Taoist ritual music

Taoism is common across southern China, including in Macao. However, the ritual music that was created in Macao was so influenced by local culture that it is now unique within Taoist music traditions.

Yueju Opera

Surviving across southern China, including in Macao, Yueju Opera is famous for its bright costumes, traditional instruments and acrobatic performances.