Checkmate! When Macao resident Herman Ho was in his first year of university in Taipei, he didn’t have anyone to play chess with, so he spent his free time taking on computerised opponents. That is, until he stumbled upon Taiwan’s chess federation about a year later. Not only did Ho develop new friends who shared a passion for chess, but the community of local players also helped Ho unleash his potential and led him to a career in the sport.

Back in his hometown, Ho hoped to find the same buzzing community that he enjoyed in Taipei. He joined the Grupo de Xadrez de Macau (GXM) – known in English as the Macau Chess Federation – and has been its permanent secretary for the past 10 years. As the secretary, he has been trying to recruit more young people to play, but until recently, interest has been scant.

Compared to mainstream sports like football, volleyball and basketball, chess has never been very popular in Macao. “The most important thing is not to push or develop the sport but to keep it,” says Ho. “I just want to find people to join the chess federation and our activities. I’m not asking much – just for chess to survive.”

If the past two years are any indication, Ho might be in luck. With pandemic rules restricting travel, many people in the city have picked up new hobbies, including chess, and withdrawn from team or contact sports. At the same time, more young people have been joining the federation’s chess tournaments and casual matches, and a Finnish chess pro has started up two growing chess clubs at a local school. With this renewed momentum, there might be a chance for chess to establish deeper and more lasting roots in the city.

Finding an opening in Macao

GXM began as a small club in the 1980s and joined the International Chess Federation (FIDE) in 1994. Despite its four-decade-long legacy in the city and international standing, the federation still falls behind peers in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore when it comes to size and stability.

According to Ho, GXM currently has around 50 active members, most of whom are teenagers, who play casual matches and participate in tournaments. By comparison, Taiwan’s federation – which only became active in 2003 – has more than 1,000 members. “Chess gets more popular every year there, because in Taiwan, parents push their children to learn different activities, through which [they] can win prizes and additional marks to help them get into better universities,” he points out. “[Parents] are even willing to pay for their children’s activities, whereas in Macao, many people don’t want to pay.”

In Hong Kong, Ho says, the local chess federation also “has new members every year and its level is always improving. But in Macao, we always have the same people [joining our activities].”

Sometimes, GXM also loses familiar faces due to life pressures that force talented young players to stop playing chess competitively. It’s common, he says, for great players to take jobs in Macao’s gaming sector and stop attending tournaments due to family and work obligations. And so the federation frequently finds itself facing a brain drain, as young talents shift focus to their studies or career. “Normally, after graduating [from school] … they leave the city to study overseas, so only a few continue to join the federation’s activities,” says Ho.

“Especially now that the economy is getting worse due to the pandemic, I can understand that everyone has to take care of their living [situation] rather than spending extra time and money [on] chess.”

Ho also points out that Macao’s relatively small population makes it harder to find and cultivate chess pros. Despite these complicating factors, chess has enjoyed something of a revival recently. During the pandemic, many people looked for new hobbies that challenge the mind, calm the nerves and are relatively easy to enjoy while social distancing.

Since chess requires only two people to play, it attracted many new and returning players. In addition, the federation has been able to hold games and even some tournaments during the pandemic, unlike many team or contact sports.

GXM has seen three times the number of participants at its tournaments and casual games in the past two years when compared with pre-Covid-19 turnouts. At the group’s last two Rapid Tournaments – a series of 10-minute matches held on 23 and 30 April – more than 30 people joined each event, and the youngest participant was six years old.

“In the past, only 10 people would join,” says Ho. “Maybe [it’s] because there are not many other activities [available during the pandemic].”

New energy from an international master

Prior to the pandemic, GXM regularly sent teams to international tournaments. The last time a Macao team attended an event overseas was in 2018, at the Chess Olympiad held in Batumi, Georgia.

Due to ongoing travel restrictions, the federation hopes to make the most of the local momentum with its annual Macao Open, held every October. Among those looking forward to the event is Macao’s top-ranked competitor, Heikki Kalevi Lehtinen, who always goes to watch the matches.

Although he isn’t playing this year, the 42-year-old father of three competed in the Macao Open twice, in 2015 and 2019, and won both times. He also holds Macao’s highest Elo rating – a skill-level rating system in chess – of 2389. (As a reference point, chess Grandmaster Magnus Carlsen from Norway currently holds the world’s highest Elo rating of 2882, and the highest level possible is 3400 – a level only computers have achieved.)

Born in Tampere, Finland, Lehtinen learned to play chess when he was just five years old, competing against his older brother, father and grandfather. Lehtinen joined his first competition when he was seven and represented Finland for the first time at 10 in the 1991 Nordic Junior Championships held in the Faroe Islands, where he won the bronze medal.

Lehtinen continued to represent his country in national, regional and international chess events for many years, and in 2004, he achieved the title of International Master, the second-highest chess title, behind only grandmaster.

In the 2008 Chess Olympiad in Dresden, Germany, he met his wife-to-be Annie, who represented Macao at the tournament. They married in 2010 and lived in Tampere until 2015, when they moved to Annie’s hometown of Macao. Now Lehtinen teaches mathematics at the School of the Nations (SON) and runs two after-school chess clubs.

Thanks to Lehtinen’s club, a new generation is starting to fall in love with the game. “It’s very popular among our students. Currently, we have 40 students in two different groups: middle [grades 6 to 8] and secondary schools [grades 9 to 12], Lehtinen says. “Students like to compete with each other. The rules in chess are easy to learn, so they enjoy playing chess during recess,” he adds.

Not surprisingly, Lehtinen and his wife have passed their love of chess on to their children: 10-year-old Anja, seven-year-old Elias and four-year-old Matias. The older two regularly join GXM’s tournaments and activities.

“One can play chess at any age. It’s a great way to develop concentration and logical thinking skills and helps players increase their creativity skills,” he says. “I’m encouraging my children to play but not pushing them to be too serious; it’s just a nice activity that’s good for them.”

Getting Macao’s youth on board

One of Lehtinen’s protégés at SON, 14-year-old Matthew Tse, started playing chess about two years ago. Lehtinen taught him to play, but Tse says he didn’t get hooked until his friends started playing, too.

The more Tse plays, the more he appreciates chess’s social and strategic qualities. “Chess improves my concentration and my calculation skills. I learned from chess that you have to be patient; if you are impatient, then you will most likely lose,” he explains.

As a promising sign for GXM, Tse says he can see himself playing for many years to come. “It has become a part of my life; I practice chess every day.”

Tse can rattle off his favourite players – Magnus Carlsen, Levy Rozman, Hikaru Nakamura and Eric Rosen – but respects his local mentor most. “I look up to Mr Heikki [Lehtinen] because he was the one that got me into chess and he is very inspirational for us students,” he says.

In addition to hosting chess clubs, Tse would love to see Macao schools invest in developing chess further. “I think many people my age are not into chess because it’s too much work for them. People my age are often busy studying or doing other activities,” Tse admits. But he thinks if schools encourage Macao students to give chess a try, they might be surprised by how much they enjoy it.

Apart from being a nice way to spend free time on a late afternoon or over holidays, chess tournaments tend to be social events, where players make new friends, like Ho did when he first got involved with the chess federation in Taiwan.

But it is the challenge of winning a game that perhaps attracts most players. For Ho, chess is also about sportsmanship and dealing with defeat – on and off the board. “In chess, there’s always a winner and loser,” he says, “and so you learn to accept loss, as is the case sometimes in life.”

Though he remains concerned about the game’s long-term popularity after the pandemic, Ho holds out hope that chess will grow in Macao – maybe not to the level it has in Taiwan or Hong Kong, but enough to give it a stronger foothold in society.

“[For instance] at the moment, we have around 10 students [who play chess]. Maybe two to three have the potential to develop further, but after graduating, maybe only one will keep playing chess,” says Ho. “I hope with more students taking an interest in chess, [that number will start to grow].”

Meet the Grand Masters

Get to know the five greatest chess players of all time according to www.chess.com.

Anatoly Karpov

Karpov was the World Champion from 1975-1985 then went on to become the FIDE World Champion from 1993-1999. In 1993, Kasparov broke away from FIDE and eventually became the subject of Tibor Karolyi’s two-volume work, Karpov’s Strategic Wins.

Bobby Fischer

Fischer was the first and only American world champion, and many consider him to be the most famous chess player in history. From 1970-1971, he won 20 consecutive games against world-class opposition – one of the game’s most impressive winning streaks. Adding another feather to his cap, Fischer’s book, My 60 Memorable Games, remains one of the best books on chess ever written.

Garry Kasparov

Kasparov held the world title from 1985-2000. He reached the top of the rankings in 1984 and, barring a few minor exceptions, remained the world’s No. 1 chess player until 2006. He reached his peak Elo rating of 2856 in 2000 – a record Magnus Carlsen surpassed in 2014.

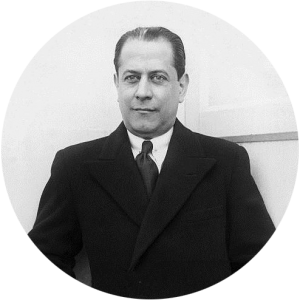

José Raúl Capablanca

Dubbed the ‘Human Chess Machine’ by many, Capablanca reigned as the World Champion from 1921-1927. He learned chess at age four and defeated Cuban champion Juan Corzo at 13. He’s best known for amassing a record 40 tournament wins and 23 draws during an unprecedented eight-year winning streak from 1916-1924.

Magnus Carlsen

The reigning world champion, Carlsen became the youngest player in history to reach the 2800-rating threshold in 2009. In 2014, he peaked at 2889, which is still the world record, and has been the world’s No. 1 player since 2011.

Some of the many benefits of chess, according to Heikki Kalevi Lehtinen:

- It improves memory focus and concentration

- It trains problem-solving and strategic thinking skills

- It develops better planning and creativity skills