Cousins Dr Tânia and Dr Sara Évora, both from Macao, have been fighting COVID-19 in Portugal for the past five months. They once felt ‘real fear’ but have now adapted to the challenge of life on the frontline.

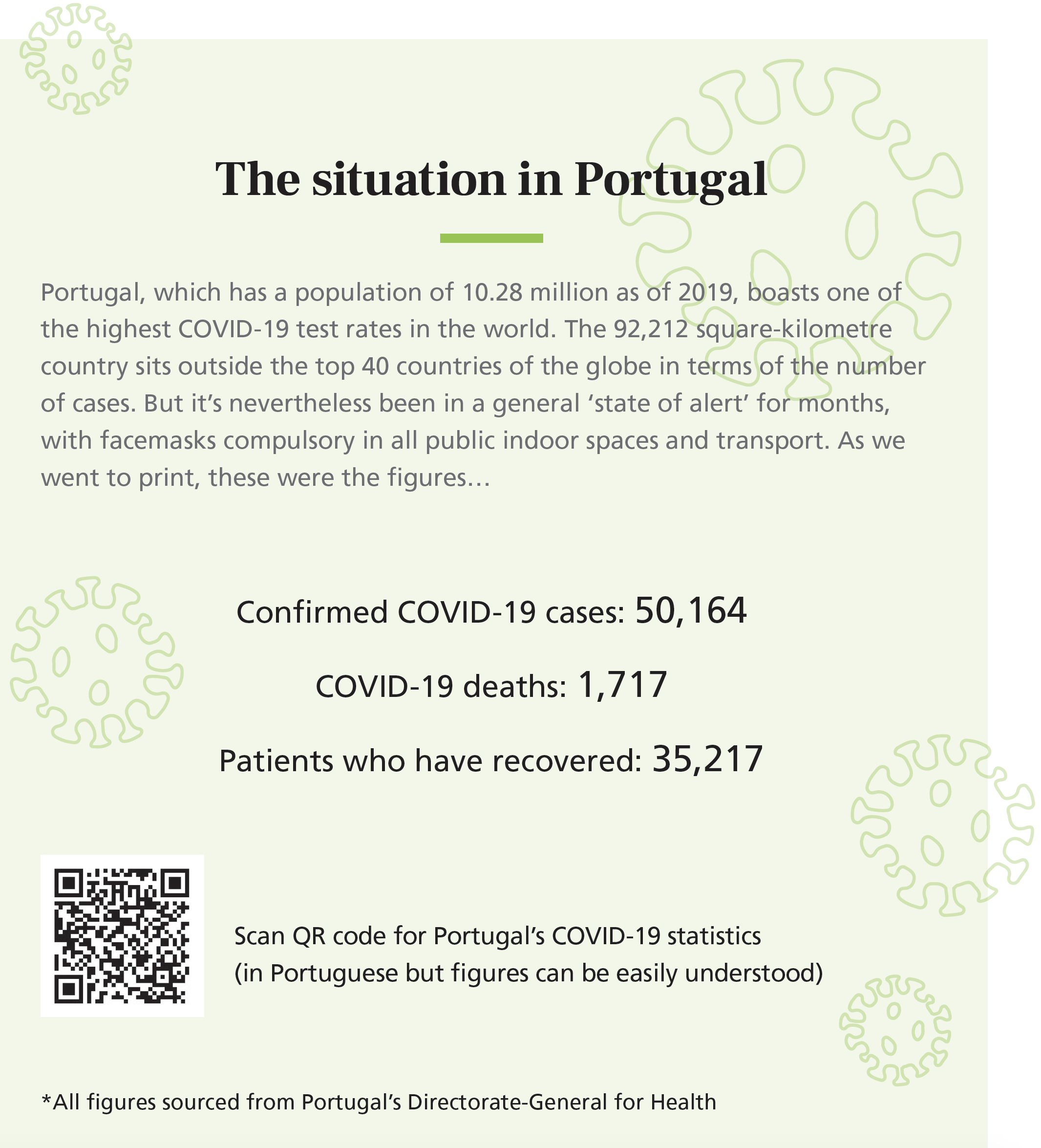

The COVID-19 pandemic has been raging on for more than six months now and when it will all be over is anyone’s guess. Macao has fought a successful battle against the virus, however many European countries have not been so lucky. And that includes Portugal, which, as we went to print, had more than 50,000 confirmed cases and had experienced more than 1,700 deaths. Life has been tough on the frontlines for the nation’s medical staff.

Two cousins who are originally from Macao are among those thousands of medical personnel on Portugal’s frontlines. Dr Tânia Évora and Dr Sara Évora have been battling the virus in medical zones in and around Lisbon since the first cases were recorded in the country on 2 March. Dr Tânia, based at a Family Healthcare Unity centre in the Costa do Estoril, a coastal area to the west of Lisbon, and Dr Sara, based at an FHU centre in the parish of Matriz in the district of Évora, which is about an hour to the east of Lisbon and shares the cousins’ family name, have not had it as tough as many medical professionals in the big hospitals but it’s nevertheless been a challenging time for them.

Due to the Portuguese government’s restrictions on social gatherings as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the cousins meet us in Poets Park on the outskirts of Lisbon and describe their lives on the frontlines over the past five months. In the hospitals, doctors have been dealing with the severe cases and the deaths. But the Évoras only deal with ‘patients with light to moderate symptoms who don’t need to be admitted to hospital’, says Dr Sara, who adds that these patients ‘make up about 80 to 85 per cent of all the cases in Portugal’. “In this country,” she says, “we have around 1,900 patients per family doctor. We need to care for the positive and suspected COVID-19 patients – who we deal with every day – but we also need to continue our care for the other patients too. It’s a challenging time for all of us.”

I wore a facemask in a supermarket in Portugal. People thought I had the virus. I felt a bit like an alien.

Dr Tânia says that ‘thanks to an intricate system put together quickly and efficiently on the part of the authorities’, the cousins have been able to deal with the virus patients as well as the regular ones out in the field. “We are routinely assigned to a COVID Dedicated Area [CDA] for a week, depending on our district,” she says, adding that these zones are in isolated locations and are often set up in temporary military-grade tents. She says that any member of the public who suspects they have caught the virus – either because they are showing symptoms or because they’ve been in contact with someone who’s tested positive – will be directed by their doctor or by personnel on Portugal’s 24-hour COVID hotline to visit a CDA.

Inside the CDA, says Dr Sara, the patient is tested and, if the results come back positive, professionals like the two doctors must follow up – meaning they need to ‘make daily individual phone calls’ to them, taking notes of their temperatures and the ‘overall state of their symptoms’. “In some cases,” adds Dr Tânia, “we might need to do house calls, although those are exceptions to the rule.” The cousins both agree that the job, under the circumstances, is anything but easy but it’s become a necessary part of life on the frontline.

“I felt real fear in the beginning,” admits Dr Tânia, who has a four-year-old daughter, “but it was not for myself. It was for my family – especially for my father and grandmother in Portugal because they are older and could be vulnerable to the virus. At home, my partner and I decided, after much consideration, that we were not ready to give up family life, so I have been extra careful when I get home to ensure that I do not bring anything back from my job. Some doctors opt to not go home when they’re working in the CDAs.”

For Dr Sara, there has been less pressure on her home life during the pandemic. “I live alone in Évora and my partner is staying in Lisbon,” she says. “I try to come to Lisbon every weekend, when possible. It has helped a lot that my father, who is still in Macao, has been relatively relaxed when it comes to this ordeal. The first time I spoke to him on the phone about this, he calmed me down. My main worry is our grandmother in Portugal, so I haven’t seen her since the lockdown started in March.”

Making a difference

Long before the pandemic began, both women chose to specialise in general and family medicine as they felt it gave them ‘the best tools to help make a difference’. “As family doctors,” says Dr Tânia, “we get to accompany patients during their lifetime. We are their first encounter with healthcare.

Medicine is in the cousins’ family. Dr Tânia’s father, Dr Humberto Évora, specialises in sports medicine and Dr Sara’s dad, Dr Mário Évora, is a cardiologist. Their family connection to Macao goes back to the 1940s when their maternal grandparents first arrived in the city from Cabo Verde, a Portuguese-speaking country in Africa. A few years later, the grandparents’ daughter and her husband joined them, bringing their first-born, Dr Humberto, with them. Dr Mário was born in the city shortly afterwards. Dr Tânia was born in Macao in 1985, however Dr Sara was born in Portugal and moved to the territory three years later, aged just six months old, as her side of the family had briefly relocated to Europe. Both women consider themselves to be ‘Macao-Portuguese’.

The doctors moved to Portugal to complete their medical degrees a few years ago. While Dr Tânia opted to live in the capital, Dr Sara moved to Évora. Both women undertook four-year residencies in Portugal, although Dr Sara spent a part of hers in Macao, finishing earlier this year. With medicine in their blood, it is not surprising that they both felt drawn to the subject from an early age.

Dr Tânia says she ‘wanted to be a doctor since she was a child, always asking her parents for books on health and the human body’. It was ‘slightly later’ when Dr Sara became interested in human medicine but she does admit she had ‘wanted to be a veterinarian since she was a little girl’.

Learning from Macao

Both cousins are thankful for their close connection to Macao as they claim they became ‘better informed during the initial phase of the pandemic’. “We felt we were two months ahead in terms of information,” says Dr Tânia. “This is not only because events developed earlier in Asia but the fact that we had lived through the SARS pandemic in 2002 also helped us calm down and face the problem head on.” The 35-year-old, at the start of the pandemic, went to the supermarket wearing a mask. She says people were afraid of her. “They thought I had the virus,” she says. “In their minds, why else would I be wearing a mask? This was about a month before the usage of masks indoors became mandatory in Portugal. I felt a bit like an alien.”

For Dr Sara, who is 32 years old, her close ties with Macao helped her feel more secure. “I remember that everyone at work was in a state of panic,” she says. “People who knew I had family in Macao often came to me for advice. Macao has dealt so effectively with COVID-19.” Both women were also pleased about another connection with Macao: when they were short of personal protective equipment (PPE), their families sent items like facemasks to them. In fact, Dr Mário Évora, who is the president of the Macau Cardiology Association’s board of directors, sent PPE like surgical masks, gloves and thermometers to the FHU in Matriz at one point. “We distributed them not only to staff,” says Dr Sara, “but also to kindergartens and elderly homes.”

“It’s been a scary time for people across the world,” says Dr Tânia. “It’s no different in Portugal. But there are signs of hope that the first part of the battle is being won and we all hope we will learn from it in the future. I’m just happy to have played my part.” “And so am I,” agrees Dr Sara. “We are thankful we became doctors and have been able to help save lives.”