TEXT Catarina Mesquita and Mariana César de Sá

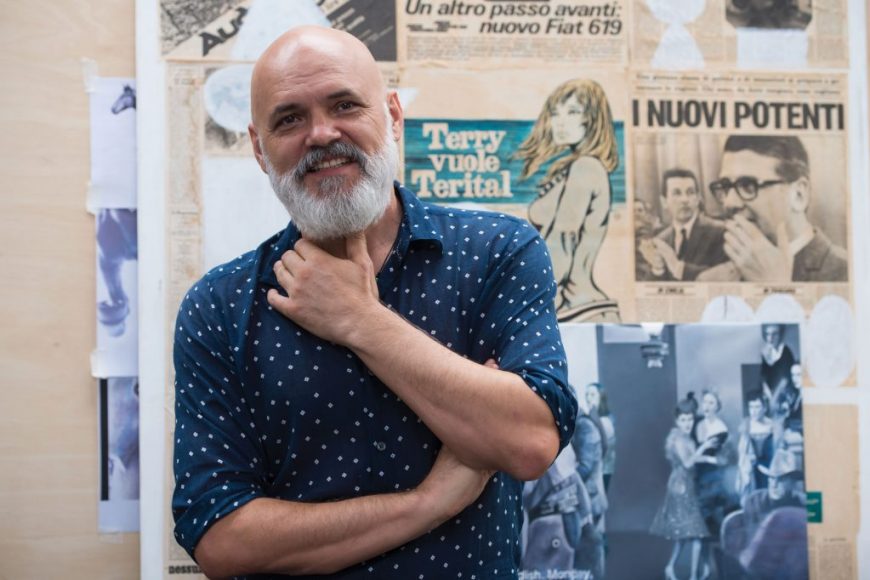

Konstantin Bessmertny presents his largest exhibition to date – Ad Lib – at the Macao Museum of Art

Russian-born artist Konstantin Bessmertny has resided in Macao since 1992, becoming a fixture in the local art scene. In November 2016, his artistic vision came to fruition with the advent of an exhibition that was finally put together after a very long time.

What is the objective of the exhibition Ad Lib. What are you trying to achieve?

The objective of the exhibition is per usual: a challenge for the artist. Life is getting one challenge after another: the bigger the challenge, the more interesting the life of the artist.

This exhibition is the result of many years of work, probably five or so. One of the works dates from almost 13 years ago, and the last one was exhibited in London 10 years ago, but most of the works are recent and reserved solely for this show. A few years ago, I began convincing Macau Museum to allow me to vandalise their space, and I’m happy to use it now.

Can you tell us about the project 365?

365 was meant to be mere discipline. It started as a simple exercise where I would begin every morning with one sketch, photography or whatever else using the same-‑sized paper. I cut the papers and arranged them on their corresponding dates. The 15th of September marked the end of Mid-‑Autumn Festival holiday and the beginning of my work. The first week of the exercise was sort of an adjustment, but after some weeks, I realised this could be a sort of project, and so I started working on it as an artistic project.

In the end, it was quite interesting to me, and I’ve received suggestions to organise it as a limited edition show. This is the second time I have had all the pieces together in one place, and I feel like I should start another one.

Is it hard to stay creative for 365 days of the year?

No. I have a large sketchbook, and I do sketches every day. Even at night time, I have it close to me. Sometimes I even sketch with my eyes closed so I don’t forget the next morning, and then during the day, I go back to it. It’s very easy for me to create every day. The 365 project is just a way to better organise and present pieces as a collective artwork.

Your works have many historical references. Which historical moment has had the most impact on your work?

I don’t have just one moment. I like history: I read books and listen to audiobooks in the car. On the way here I was listening to a piece on the liberation of slaves in Russia and the United States of America.

If I had to pick one historical reference regarding Russia, it would be perestroika, because it was a recent event and a nice period in the country’s history. Some time ago I had difficulties understanding Gorbachev’s policies, but now I think he could be the most progressive politician of the 20th century.

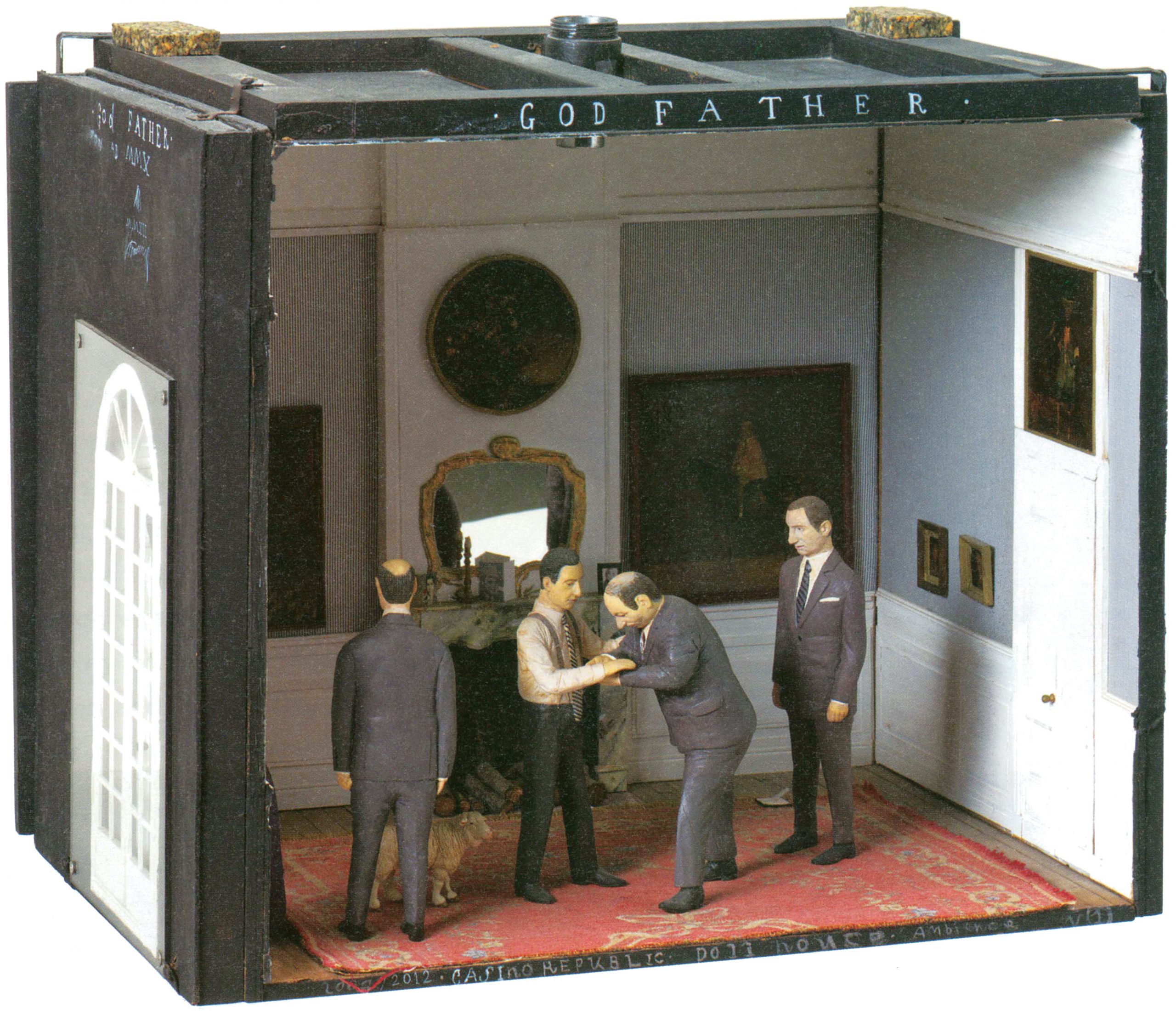

If there were a fire in the museum and you had only one minute to leave, what work would you take with you?

I would probably take the dollhouse. Not that I like it, but I spent and wasted so much time on it that I would be valuing my time. The car I couldn’t take because it’s too heavy, and the paintings I would have to dismantle. The dollhouse is the smallest and the easiest to carry; at the same time, it is the most complicated piece in the exhibition.

Since the opening, what has been the public reception so far?

I am so used to empty spaces in museums that I was impressed with the response. I have seen a lot of people, especially young people and teenagers, so I’m happy. I think they are looking for something that I managed to touch upon which is a compliment that gives me confidence in what I’m doing.

Was the Macau Museum of Art open to the content of your work featuring a lot of political figures which can be a quite sensitive subject?

Yes. Despite the variety of subjects, I never felt that I had to censure myself or received any external censure. I had some doubts whether some works could be exhibited, but at the same time, even I have my limits. For example, I can’t insult politicians or celebrities, and I don’t want to vandalise something that might be sacred for others. As an artist, you work on the frontier dividing acceptable from unacceptable. I try not to get as close as possible to this line because there are many other honest ways to do your work without inciting too much attention crossing those boundaries.

Do you have any artistic references or inspirations?

In life, there is always someone who comes along and kind of guides you. I have a big gallery of characters and artists who inspire me. I am always discovering more, for example, I recently discovered an aspect of Salvador Dali’s work that I found interesting, and it makes me wonder whether he is one of the most underestimated artists of the 20th century.

What’s next for you?

Sometimes you don’t want to share your plans because you don’t want to spoil and ruin them, but I have a lot of on-going projects: one is on hold in London due to Brexit, and I would love to do something in Moscow, Beijing and Shanghai, which are all on my list.

KONSTANTIN BESSMERTNY

THE CULT(URE) OF IRONY, SARCASM AND CREATIVITY

António Conceição Júnior, Cultural Consultant of Macau Museum of Art

One could argue that among the roles an artist embodies, that of ethical advocate intervening at a social level is of paramount importance. This is undoubtedly the underlying purpose of the works presented in Konstantin Bessmertny’s exhibition Ad Lib (short for “ad libitum,” Latin for “at one’s pleasure”).

Ad Lib is possibly the most important exhibition put on by a resident artist of Macao since the 1980s. This landmark show boldly challenges the city’s cultural institutions, namely the Macau Museum of Art: who will be the next artist capable of such a feat of the eye and the mind? In the shadow of this monumental exhibition, painting itself may become a banality, even a vulgarity.

What has become frustratingly obvious in light of this exhibition is the general failure to understand high art in Macao. The prevailing notion is that, indeed, anyone can paint, so the general public perceives Ad Lib as merely “another painting exhibition,” that is, another attempt at fulfilling the exercise of painting. What a pity that very few seem to appreciate that beyond the highly learned and immensely skilled artists of the Tang dynasty or the Renaissance, there is yet a vast universe of worldly experience and culture.

SARCASM

The clear problem of the outlawing of insult is that too many things can be interpreted as such. Criticism, ridicule, sarcasm, merely stating an alternative point of view to the orthodoxy, can be interpreted as insult.

Rowan Atkinson (Actor)

In order to understand Bessmertny’s work, it is imperative to be familiar with his toolbox and the instruments with which he constructs his artistic universe. His is a fluid and flexible toolbox; instruments are brought in according to the needs of the artist. This sort of pragmatism, coupled with his immense capacity to appropriate objects, is one of the defining characteristics of Bessmertny’s body of work.

In a similar vein to the assemblages by Pablo Picasso, namely, Bull’s Head (1942) and She‑Goat (1950), Bessmertny selects an object his mind’s eye finds useful and creates a piece imbued with humour, irony, sarcasm and above all, the capacity to provoke and defy the austerity of art. His work is often a paradigm of a keen observation by philosopher and intellectual Marshall McLuhan: ” It is possible to deal with the entire environment as a work of art.”

Bessmertny has built his toolbox upon a unique foundation, choosing Macao as his creative environment and base from which he constructs different scenarios of one reality, seasoning each iteration with different condiments. This artistic equation is rather like a loose recipe to a grande boeuffe (a big feast).

THE SPECTACLE OF LIFE

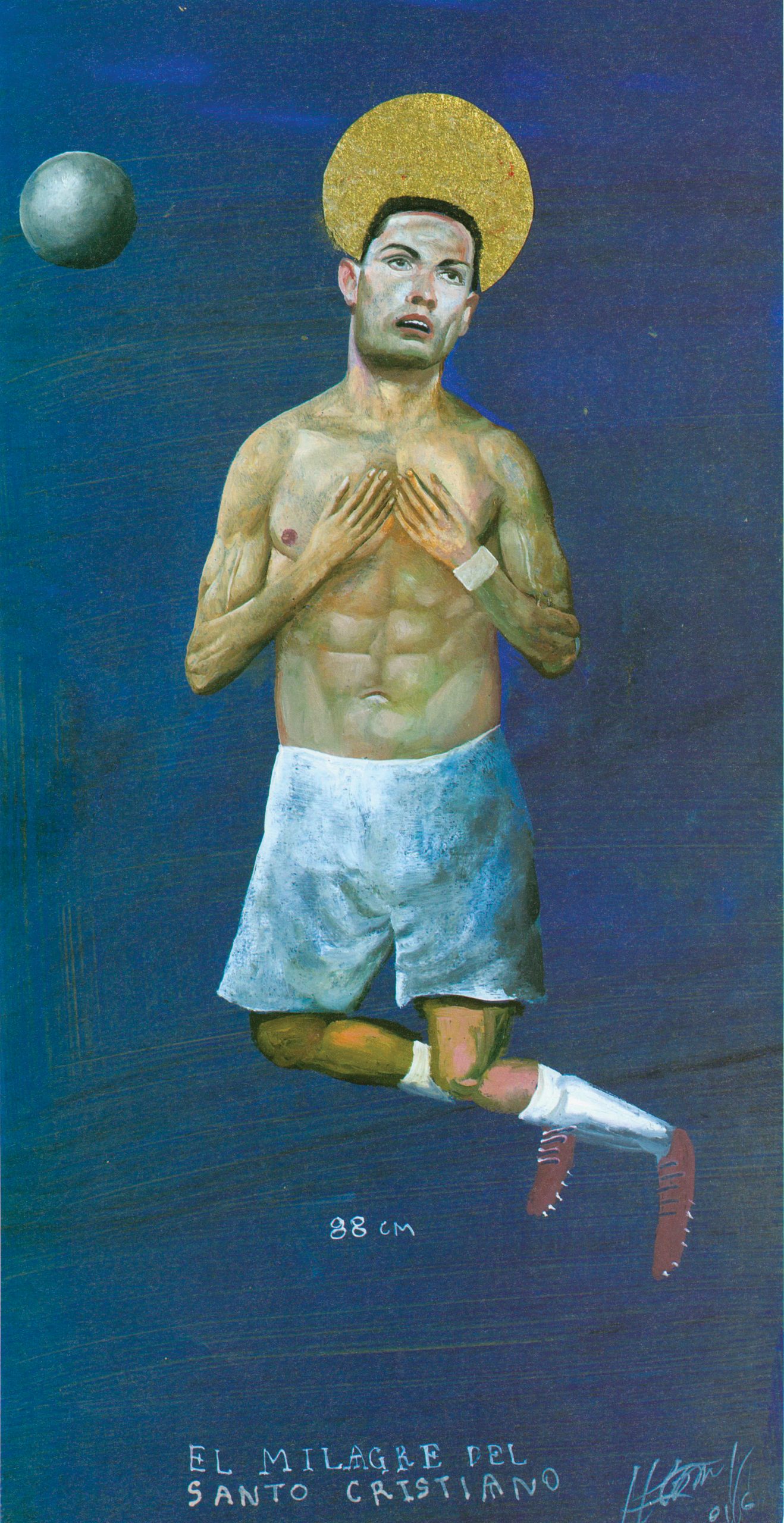

One of Bessmertny’s prevailing themes is the distortion or transformation of an object of desire into an object of parody and decorative functionality.

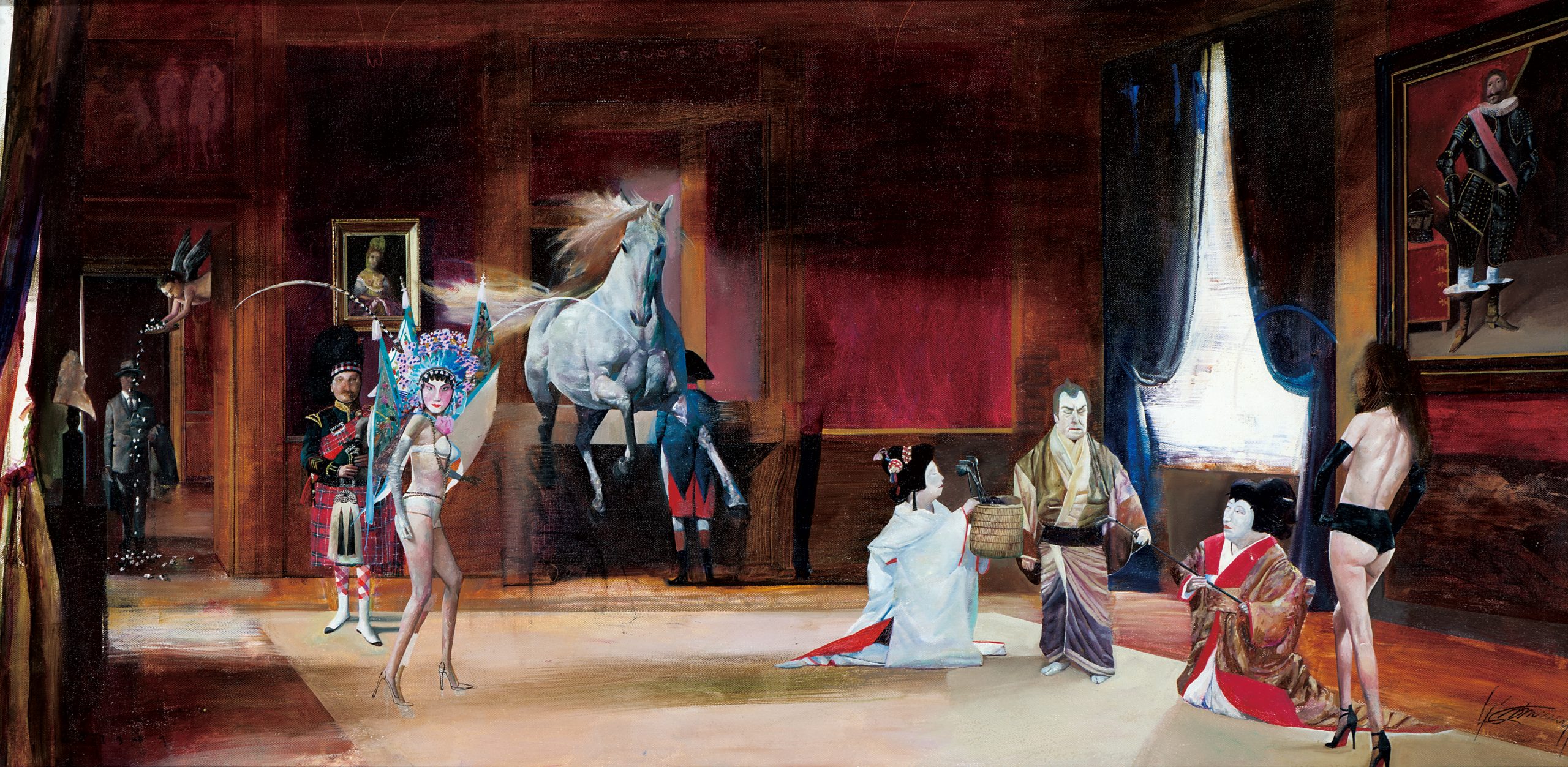

Indeed, his works embody the narrative of Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa’s Notes on the Death of Culture: “The civilisation of the spectacle has not just administered the coup de grâce to the old culture; it is also destroying one of its most sublime manifestations and achievements: eroticism.” Revolving around this theme of eroticism, Bessmertny’s paintings often depict scenes of cultural misappropriations in an absolute feast to both the eye and the mind. Scenarios centred around imaginary personalities as well as royalty are especially provocative, for example, his magnificent rendition of L’État c’est Moi featuring King Louis XIV. In this work depicting kitsch culture bordering on the bizarre, each character is misplaced and out of context, resulting in a parody of the power of money or status quo. This conclusion unifies all the works in the current exhibition.

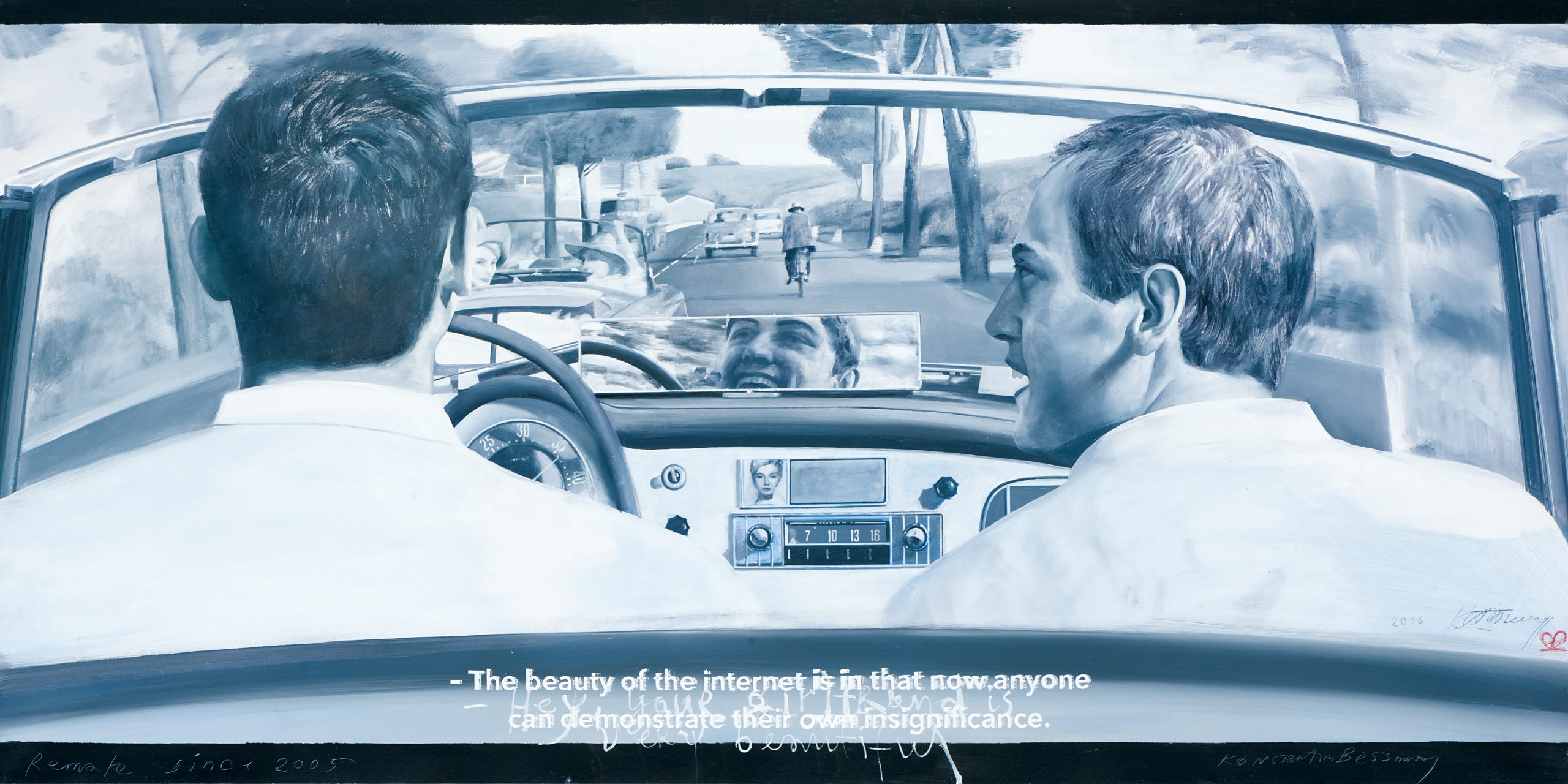

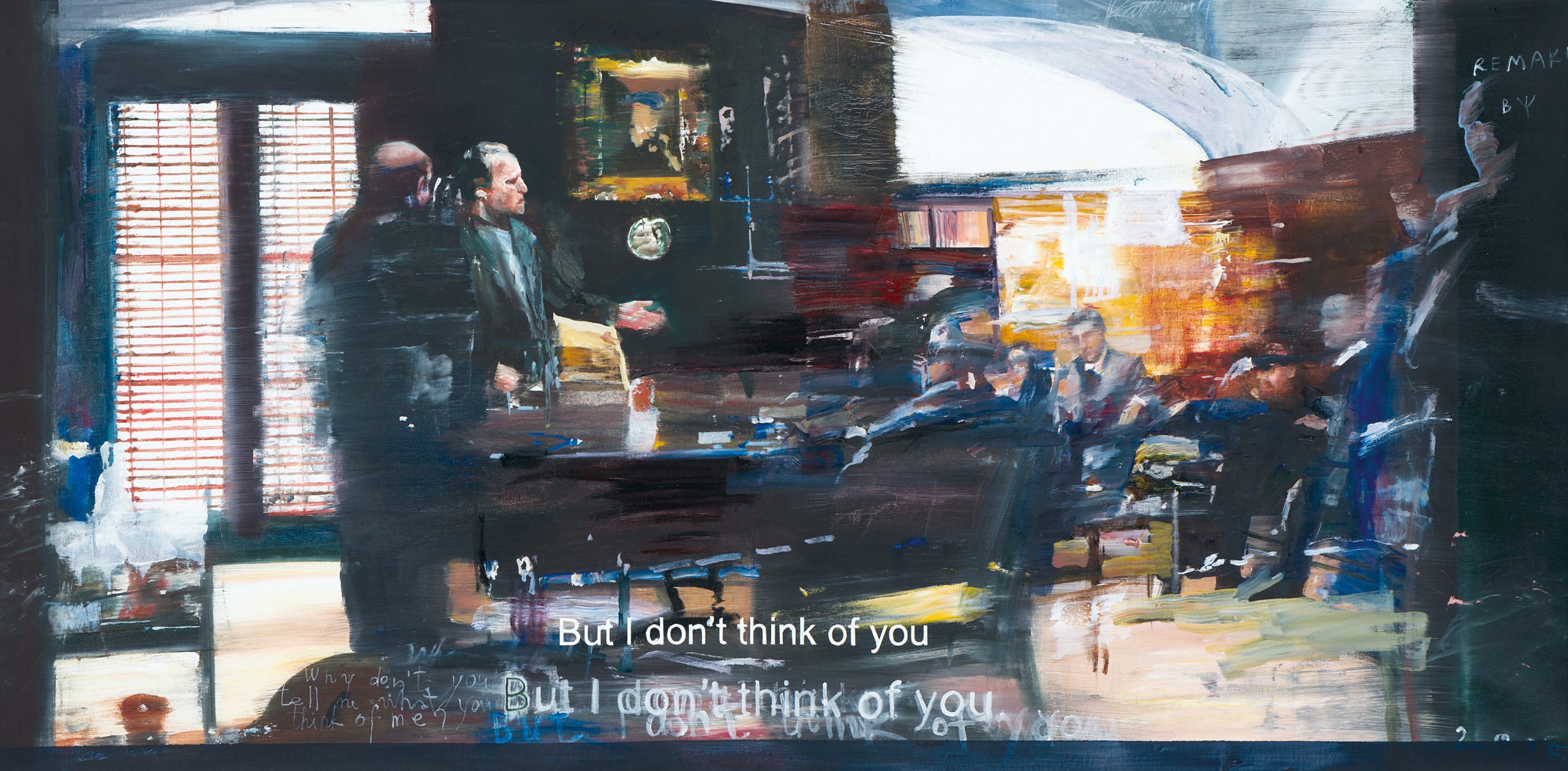

THE OIL OF CINEMATOGRAPHY

In the late 1960s, Portuguese painter Artur Bual prophesied that the artistic language of the future would be the cinema. Bessmertny inverts this prophecy by referencing cinematic scenes to demonstrate inflation of ego across society, in Macao and abroad.

His metaphors are corrosive phrases that read like subtitles: photograms transcribed in oil onto canvases in the format of a cinemascope. Historically, as ego grows, so too does the desire for power. Conversely, the insignificance of the majority of uneventful human lives becomes exaggerated. Bessmertny’s works are metaphors to the banality of materialism left to individual interpretation. His cinematographic paintings destroy the vanity of his characters who represent iconic symbols of ignorants unaware of their own limitations. Bessmertny is the Jean de La Fontaine, 17th‑century French fabulist, of the 21st century.

Of course, given the attitude of his work, it is important that the artist possesses the capacity to parody himself, incorporating his self‑portrait within a critique of the art world that sustains him. In ridiculing the vampirism of the art world and himself, Bessmertny legitimises his authority to present his view and judgment of this world. The subtitle of his Godfather painting, “But I don’t think of you,” is an example of the juxtaposition of artist and medium.

The perception of power and its subsequent carnage, two overarching themes throughout his work, are subjectively interpreted in one of K.’s paintings featuring different iterations of the geisha.

REFLECTIONS ON THE FUNCTION OF PORTRAITURE

Aristotle stated, “The aim of Art is to present not the outward appearance of things, but their inner significance; for this, not the external manner and detail, constitutes true reality.”

Portrait painting carries a long tradition of depicting those in power, providing visual evidence of kings, queens and noblemen throughout history. These pieces, painted by innumerable artists from both East and West, were understood to be serious, well‑regarded and “well‑behaved” works of art.

Bessmertny spares no one in his depiction of the powerful, for example, depicting a contemporary Queen Victoria on a large canvas with long nails on her right hand, both hands and wrists decorated with bracelets, holding a fan and adorned with various ornaments throughout her dress. His treatment of two portraitures of Grigori Rasputine and Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin is along a similar vein. He is more interested in the great spectacle of life than the Aristocratic definition of portraiture, although he is far from being distanced from reality.

Ultimately, the task of deciphering Bessmertny’s imagination and creativity are left to the viewer, for good art is not easy to perceive. People must see beyond the surface, beyond the obvious to what lies beneath.