Brazilian jiu-jitsu – the most popular martial art in Brazil – is edging its way into the mainstream. It’s got a slew of big names hooked, including Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and entrepreneur Elon Musk. It’s even got a small yet passionate following in Macao. There are at least five Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ) black belts in the city, according to Tiago Afonso, the co-founder of Macao’s most prominent BJJ academy.

Jiu-jitsu’s roots are in ancient Japan, though the art was formalised around the 17th century. That’s when it evolved into a distinct unarmed fighting style practised by samurai on the battlefield. Techniques include takedowns, leg sweeps, joint locks, and chokeholds; in other words, grappling. A literal translation of ‘gentle art’, jiu-jitsu’s name belies the fact that samurai used it to kill. The ‘gentleness’ came in the form of using leverage and strategy over brute force. The original jiu-jitsu fighters were known for effectiveness against armed opponents.

In the wake of the samurai era, in the late 1800s, jiu-jitsu was reinvented by a man named Kanō Jigorō. Kanō began learning the techniques as a child, to defend himself against bullies, and went on to become a highly revered martial arts teacher in Japan. He developed a less lethal style of jiu-jitsu. Submission was the aim, not death. In the 1880s, Kanō founded a brand new martial art: judo.

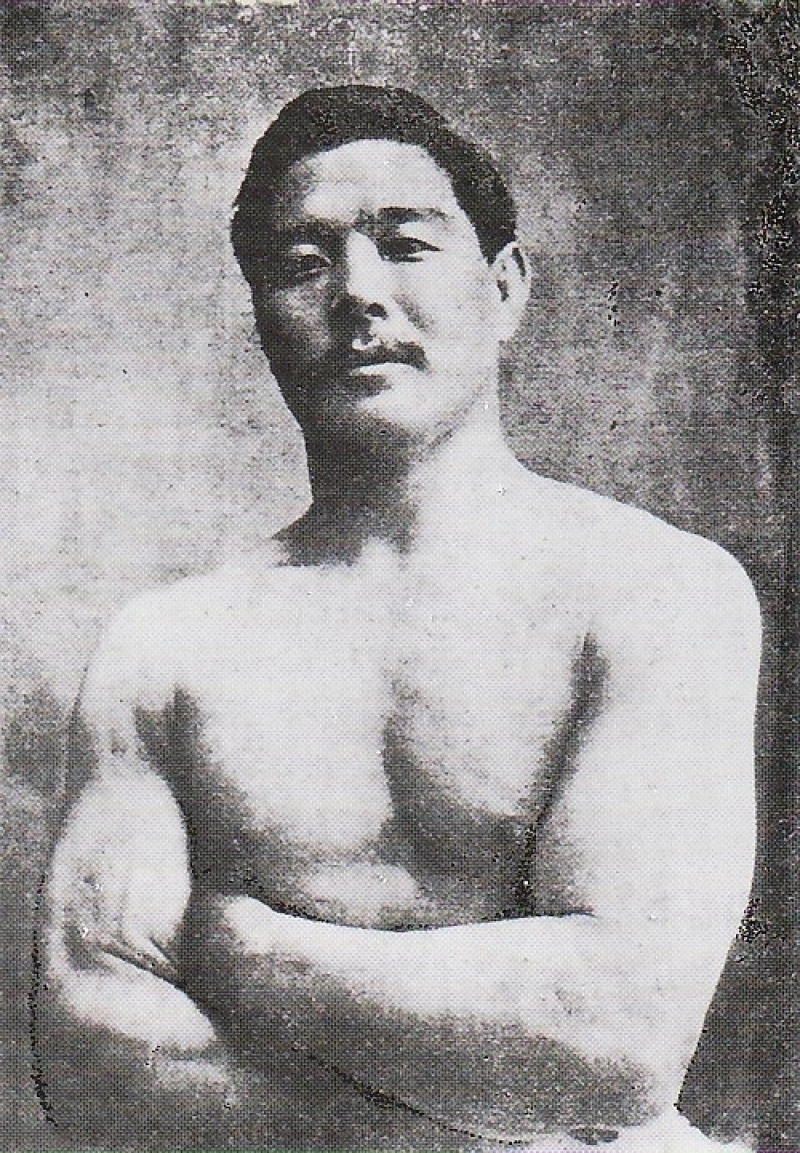

It was Kanō’s protegee, Mitsuyu Maeda, who took jiu-jitsu to Brazil. Born in 1878 and an exceptional martial artist, Maeda was sent abroad to promote Japan’s martial arts. He first travelled to the US in 1904. A few years later, the Portuguese dubbed him ‘Conde Koma’ – Conde being Portuguese for ‘Count’, and koma, short for the Japanese word komaru, meaning ‘in trouble’ (ie the state any opponent of Maeda would find himself in).

Maeda reached Brazil in 1914 and proceeded to impress a prominent businessman named Gastão Gracie with his jiu-jitsu skills. The men became friends; Gracie sent his 14-year-old son, Carlos, to learn martial arts under Maeda. Maeda convinced him that practising jiu-jitsu would help the wayward Carlos gain self-confidence and focus his energies.

He was right. In 1925, Carlos established the Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Academy in Rio de Janeiro. He and his four brothers are credited with developing the sport now known as Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

The major difference between BJJ and its parent sport (or, art) is that the latter uses more attacking techniques. BJJ focuses on defence, and is all about getting your opponent to the ground without causing them undue pain. As such, they have morphed into separate sports, with different rules. Many traditional jiu-jitsu moves are banned in BJJ competitions, for example.

Today, the Gracie family remains heavily involved in BJJ. There are between 150,000 to 200,000 BJJ black belts worldwide, according to available statistics, and most are based in Brazil. While BJJ is not an Olympic sport, the International Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Federation organises annual World Championship tournaments. Many BJJ jiujiteiro (a Portuguese word meaning ‘jiu-jitsu addict’) also practise mixed martial arts (MMA) – which incorporates BJJ techniques.

Brazilian jiu-jitsu in Macao

Two trained lawyers believe they are Macao’s first BJJ black belts. That’s Tiago Afonso and his friend, Luís Serafim. The pair received their belts together in 2015, from the Hong Kong-based BJJ and MMA teacher Rodrigo Caporal.

Afonso and Serafim first met in 2007, at a mutual friend’s birthday party. They quickly got talking about their shared passion for BJJ. “The next weekend, Luís was going to a BJJ class and asked if I wanted to join,” Afonso, now 51, says. “I was like sure and I’ve never stopped training since.”

That same year, the pair co-founded the Macau BJJ academy with three others in Taipa Village. It was rebranded as Atos Macau in 2019 (Atos is an international Brazilian jiu-jitsu franchise).

While basic BJJ was already being practised in the city, through a few fitness centres, Afonso says his living room-sized gym was the birthplace of Macao’s BJJ community. The early days were tough, he recalls, with just two students and no official coach. Anyone who turned up for a lesson was going to be learning from YouTube.

But Afonso and Serafim persevered. Their fledgling club’s first competition was in 2009, at the Hong Kong BJJ Open. The team from Macao placed third. An impressive feat, given the circumstances.

Atos Macau now has almost 60 registered members, including about 20 under-18s, and four instructors (Afonso, Serafim, and two brown belts). Afonso quit being a lawyer in 2019, to teach BJJ full-time. Serafim starts teaching BJJ at 6:30 am, then heads off to his desk job.

“Jiu-jitsu drastically changed my life,” Afonso says. Teaching martial arts is obviously a different lifestyle to a nine-to-five office job, but Afonso, a father of one, says the camaraderie fostered through training has led to important friendships, too.

“We try to kill each other during classes,” he jokes. “But through that, we do a lot of bonding.”

At Atos Macau, belt progression is determined through sparring sessions rather than exams. Mere survival is enough to earn a white belt. Proficient submission earns you a blue belt, the next level up. Then there’s purple, then brown, and finally black. With enough time and dedication, Afonso says it takes about 10 years to reach the highest level.

Very few people make it, however. “I think from all the people that start practising jiu-jitsu, less than 1 percent reach the level of black belt,” he notes.

For most BJJ practitioners, becoming a black belt is not the point. Some learn it, like Kanō Jigorō, for self-defence. Others do it to keep fit, or for stress relief. Personal growth is a big motivator; as is the discipline and focus BJJ instils. It’s fun, too, bordering on addictive. Afonso describes BJJ as “a bug” people catch because once they start they become obsessed.

‘It’s part of my life now’

Macao-born Elsa Sousa is a BJJ blue belt at Atos Macau. She first got into martial arts at her local fitness centre, doing a Muay Thai class in 2020. One day she noticed a new class was being offered: Brazilian jiu-jitsu. Sousa, who is in her 30s, was intrigued.

“I had no idea what it was and ended up trying one of the classes,” she says. “It happened to be a graduation class, where everyone got their belt.”

Sousa went home and researched belt levels. The next morning, she went out and bought herself a kimono (traditional Japanese robes worn by BJJ practitioners). While she now says signing up to learn BJJ was the best decision she’s ever made, Sousa admits she felt a bit lost during her first few months of classes.

“It’s not like a pilates class where you can join in and just decide you like it… BJJ is a process,” Sousa, who switched to Afonso’s academy later in 2020, explains.

She says BJJ empowers her to overcome obstacles, both on and off the training mat. The sport is designed to minimise a person’s size and strength advantages, giving petite practitioners like Sousa the skills needed to overpower larger combatants.

“It gives me at least a chance to beat the odds, and that translates into my day-to-day life,” she says.

Sousa’s passion for BJJ has already taken her to competitions in many places in Asia. She’s eager for more. “My aim is to get into more tournaments because I think it’s fun,” she says. “It’s also an opportunity for me to practise my jiu-jitsu with other girls of different sizes, since I don’t get to train with a lot of girls here.”

Getting women into BJJ can be challenging; Sousa thinks it’s because it’s a ‘fighting’ sport with a lot of close contact. So far, she’s only managed to convince one female friend to join her.

Steve Lam is another BJJ evangelist. Previously involved in fencing, the 33-year-old workforce analyst discovered BJJ in 2013. He caught the bug quickly and has risen to the rank of brown belt.

“Over the past 10 years, I fell in love with the sport – it’s part of my life now,” he says. “It lets me constantly challenge myself, break through limitations, and make myself stronger.”

Lam has competed extensively, throughout Greater China as well as in Abu Dhabi, Turkmenistan, Vietnam, Thailand and Japan.

“My next goal is to earn a black belt, and then I want to become the world Brazilian jiu-jitsu champion,” he says, with seriousness.

Lam urges people of any age to give BJJ a try. Plenty of people start later in life, he points out, citing the late US chef Anthony Bourdain – who began training in his 50s. “It’s a growing sport and I hope more and more people will know about BJJ in the future,” Lam says.

While the BJJ community in Macao is small, this martial art’s popularity is growing throughout the region. In 2021, China established the China Jiu-Jitsu Council – which promotes BJJ, as well as traditional Japanese jiu-jitsu. According to China Daily, the country’s BJJ practitioners currently number about 30,000.

Afonso is looking forward to seeing how the scene develops in Macao. “Right now the objective is to keep growing, keep the community spirit alive, and to leave a little bit of… let’s say a legacy,” he says.