Every morning, the air inside A-Ma Temple fills with the heady aroma of burning incense. Worshippers brandishing joss sticks wend their way between different altars, bowing an auspicious three times before each, as they have done for untold generations. Most prayers are directed to the sea goddess Mazu, though it’s unlikely many modern-day Macao people pray for safety in the ocean. These days they use bridges to cross the sea and have air-conditioned office jobs. Their troubles are more of the landlubber variety.

But prayer content aside, A-Ma feels remarkably like a portal to the past. The temple’s first iteration dates back to the 15th century. While much of A-Ma’s structure has been rebuilt over time, a bas-relief in the temple’s courtyard – featuring a Fujianese merchant junk – is believed to be original.

It’s not too hard to imagine the Ming dynasty fishermen who carved it praying reverently amidst the fragrant smoke. Those men were genuinely in need of a sea goddess’s intervention; in fact, they believed their lives depended on it. Mazu, of course, has been considered the protector of seafarers across much of Asia for almost a thousand years.

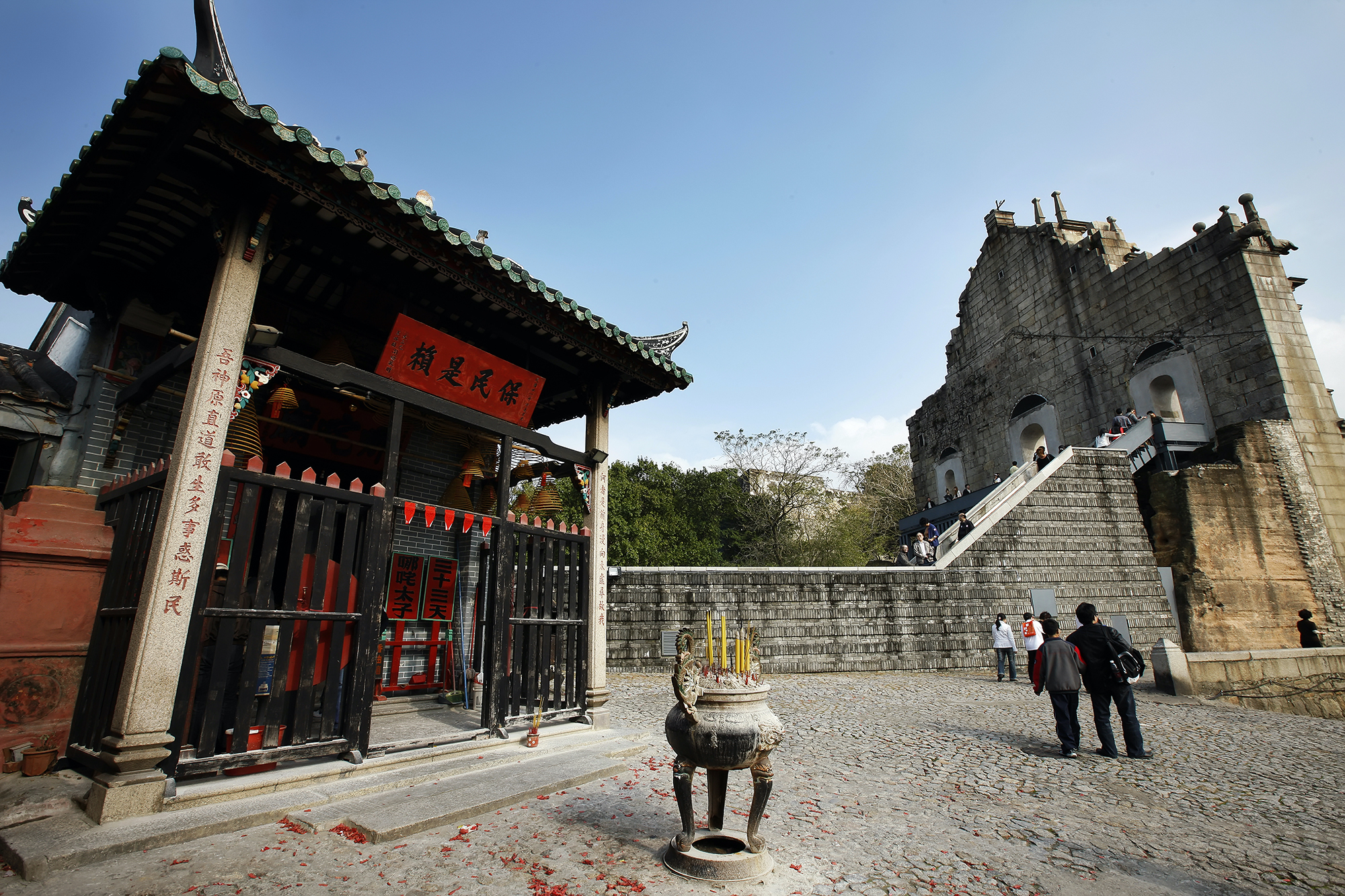

According to the Cultural Affairs Bureau, there are over 40 temples honouring Buddhist, Taoist, and Chinese folk deities atop the city’s tiny landmass – 29 in the Macao Peninsula, nine in Coloane and seven in Taipa. This includes three with UNESCO World Heritage status: A-Ma; Kuan Tai Temple, built in 1750; and little Na Tcha Temple, tucked behind the Ruins of St Paul. The latter was built in 1888, a few decades after the 17th-century cathedral burnt down following a typhoon – leaving only a skeletal façade, now an iconic symbol of Macao. That’s more temples per square kilometre than any other city in Greater China. Hong Kong, for instance, is home to around 600 temples, which makes 0.54 temples per square kilometre. Macao counts 1.25 per square kilometre.

Many have borne witness to the unfolding of Macao’s rich history. The city’s old-world temples currently provide stark contrast to the city’s glitzy casinos, which almost match them in number.

All the while, these temples have been active places of worship. Heritage expert Andre Lui notes that in much of today’s world, venerable, historically significant buildings like A-Ma are often demoted to tourist attractions.

In Macao, however, temples have remained an important part of local people’s daily lives. Lui is a registered architect, founder of CITA Planning & Design firm and a visiting assistant professor of architectural heritage at Macau University of Science and Technology.

“Visiting temples is deeply ingrained in the culture,” he explains. “Their preservation is, therefore, of the utmost significance.”

Diverse divinity

Some of Macao’s temples are Taoist. Others are Buddhist. Most, however, offer a seamless merging of the two religions – with pavilions dedicated to worthy figures from each. “It’s far more common to encounter temples that harbour both philosophies or religions under one roof,” affirms Lui. “That is the case with A-Ma.” Temples are built to honour (or harbour) gods, goddesses, warriors and Chinese folk heroes. There’s no limit to how many an especially popular entity will inspire: Mazu has five, for instance.

In terms of design, feng shui rules. As it does with anything built to the principles of traditional southern Chinese Lingnan architecture – the architectural style seen in the Lingnan region, which comprises the provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi, both located south of the Five Mountains. The Taoist concept of feng shui – which literally means ‘wind-water’ and implies the flow of vital energy – is all about enabling harmony between nature and man-made structures.

At A-Ma, for example, a series of small halls were built up a hillside to align with the temple’s main gate. The hill was not altered to accommodate the buildings, rather they exist in harmony with the natural landscape, explains Lui. “Between the pavilions built up the hill at A-Ma Temple you’ll see rocks and trees and other elements of nature mixed with the architectural structure. This is a Taoist feature.”

Lingnan architecture also imbues temple rooftops with meaning. “In ancient China, the architecture [of an edifice] reflects social hierarchy. Different rooftops reflect the social level of its owner or, in temples, rooftops reflect the level of its goddess,” Lui explains.

For example, A-Ma Temple has a wudian, or hipped roof – because Mazu is considered very high status. Tou Tei Temple, meanwhile, has a yingshan roof to shelter the relatively modest God of Land.

In terms of materials, many Macao temples are built with ‘blue brick’. According to architect and author Carlos Marreiros on ACE Macau (Architecture Culture Environment, Macau), a book published by the Polytechnic University of Milan, there are “unsubstantiated statements by some authors” that these bricks, made from a mixture of mud, straw and oyster shell lime, might have been brought over from Malacca by the Portuguese.

According to Marreiros, the ridges on temples’ roofs often boast intricate decorations depicting “mythological scenes, tales and historic narratives” made of either non-glazed or mainly glazed and multicoloured terracotta. Auspicious symbols such as dragons or carps can be seen over these ridges, “frequently centred by a cosmic pearl,” Marreiros writes.

Three temples embedded in Macao’s history

A-Ma’s original structure, of course, was built before Portuguese sailors and traders set foot on Macao’s shores. It’s a sprawling complex that’s been added onto, renovated and re-built since 1488. When the Portuguese first reached Macao in 1553, they heard locals using the term ‘A-Ma-Gau’, meaning ‘Bay of A-Ma’. They took this to be the name of the island they’d landed on, and started referring to it as ‘Amagau’, or ‘Amacao’, which eventually evolved into ‘Macao’.

The sea goddess Mazu’s origins are hazy, too. Some claim she was a 10th-century girl from Fujian Province who fell in love with a Taoism teacher. He taught her a special charm that allowed her to fall into a trance and save her father and brother from a shipwreck. Later, the girl is said to have committed suicide to escape an arranged marriage with an older man.

By the 12th century, fishermen were reporting Mazu had aided them in storms off the Fujian coast. As such, she became the venerated guardian of seafarers. In the 15th century, when Macao’s A-Ma temple was built, seafarers made up the bulk of the region’s population. According to lore, Mazu, who also goes by the name of Tin Hau, is matched in glory only by the Buddhist goddess of mercy – Kun Iam.

Kun Iam has her own sizable temple in Macao. Its first iteration dates back to the 13th century, built in Macao’s northern centre, and the current structure was completed in 1627.

Lin Fong Temple, also known as the Lotus Temple, is just 500 metres north of Kun Iam Temple and was built at the end of the 16th century. It was here where Lin Fong hosted Imperial Commissioner Lin Zexu during his campaign against opium. At the temple, Lin Zexu met with Portuguese Governor Adrião Acácio da Silveira Pinto – ordering him to ban the opium trade (and spare Macao the serious substance abuse problems plaguing Hong Kong). The commissioner threatened to cut off Macao’s access to basic food staples if Pinto didn’t oblige, which prompted the Portuguese to cease opium trading in the territory, shipping off the drug’s stock to the Philippines.

Today, a six-foot tall granite statue honouring Lin Zexu stands at Lin Fong Temple’s entrance. The Lin Zexu Memorial Museum resides within the temple’s spacious courtyard, offering insights into those troubled times.

Preservation efforts: not just Macao’s heritage

Macao’s older temples wouldn’t be here without significant investments into their preservation. Most temples – including those three – are managed by non-governmental temple associations, funded both by donations and the Macao government. They carry out day-to-day maintenance and minor repairs. More in-depth restoration projects are handled by the Department of Cultural Heritage, part of the government’s Cultural Affairs Bureau (ICM).

ICM has undertaken 23 major temple restoration projects in the last five years. Most recently, it tackled Coloane’s Tin Hau Temple, which was built in the mid-18th century. In a written reply to Macao Magazine, the bureau describes the restoration as “mostly repair works to the tiled roof; repairs and renovation for the wooden beams and other architectural components; cleaning and maintenance of the interior and exterior walls and stone fences; dredging storm drains and manholes; maintenance and reinforcement for indoor platforms; as well as maintenance and renovation for certain components inside the temple.”

Less extensive preservation projects are centred around preventative measures – especially in the realm of fire safety. Unsurprisingly, fire poses a considerable risk to temples. In 2016, a serious one in A-Ma’s main pavilion caused enough damage to close the temple for two years. ICM works closely with the Fire Services Bureau to run regular safety training sessions and drill exercises at temples, and carries out around 200 preventive fire inspections a year.

“Macao’s precious temples and their related culture” serve the city on social, spiritual, and economic (in the form of tourism) levels, ICM tells Macao Magazine. “[They] serve as a vital channel for residents to develop a sense of self-identity and for visitors to understand local culture.”

A-Ma Festival

Every April or May, Barra Square is the stage for the Festival of A-Ma in honour of the Goddess of Seafarers. Three elements of intangible cultural heritage merge at this lively festival: the beliefs and customs of A-Ma, Cantonese opera, and the craft of bamboo scaffolding. The goddess – and hundreds of festival goers – are invited to watch Cantonese operas perform in a massive bamboo shed erected at Barra Square for the celebration. After being thoroughly entertained, the goddess is escorted back to the temple in a show of respect and honour.

VOX-POPS

Fujian traditions:

“I grew up in Macao but my hometown is Fujian. People in Fujian usually pray to Kun Iam, which is why I also pray to Kun Iam. I come here to pray for good health and best wishes to my family.” – Chu, Macao resident

Peaceful worshipping:

“I’ve prayed in this temple [Lin Fong Temple] since I was young. It’s been so many years! I come to pray to Kun Iam for good health and safety. Praying at the temple also puts my mind at ease.” – Chan, 61, Macao resident

Faithful reverence:

“My family members are Buddhists and my ancestors’ pedestals are also in this temple, so I usually come here. I find it so comfortable and relaxing here. I hope there will be more large-scale religious events or activities in the future, such as some festivals or celebrations.” – Wu, 22, university student

Preserving temples:

“I think temples in Macao represent the city’s living memory and the culture of the people who live here, so it’s important to get them well maintained.” – Simon, 43, tourist from Hong Kong