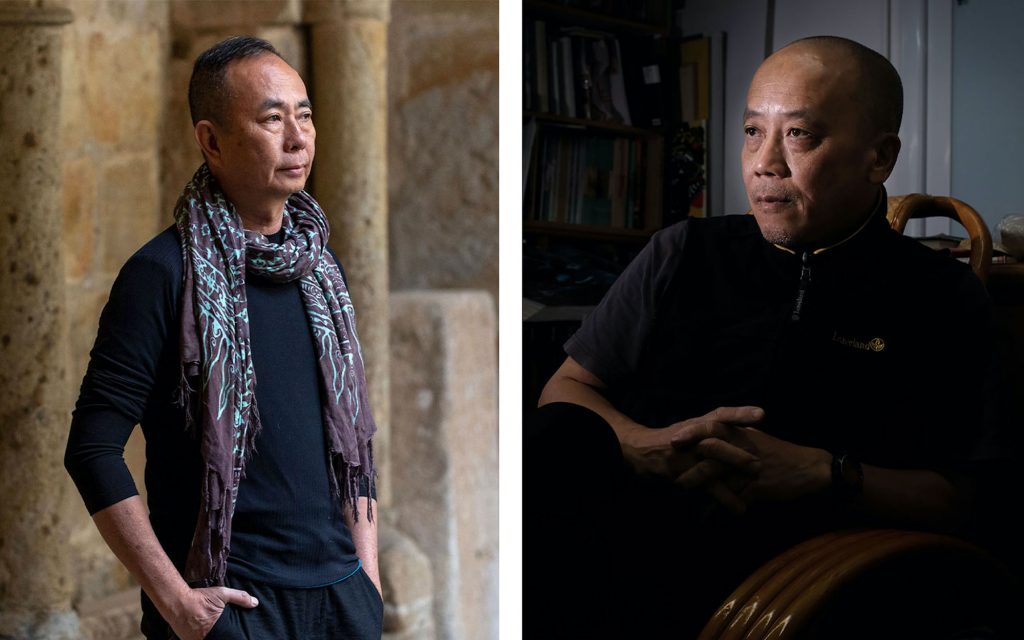

One day in 2020, a bus advertisement recruiting research coordinators for Iao Hon Estate, an urban renewal project on the Macao peninsula, near the border with Zhuhai, drew the attention of painter Ung Vai Meng and photographer Chan Hin Io. The two are co-founders of YiiMa, an art group meaning ‘twins’ that was established in 2009 and officially registered in 2019. The duo collects pieces, such as press clippings, photographs and writing, from across Macao and integrates their findings into their artwork – a style they call ‘performance art documentation’.

The two were struck by the potential of Iao Hon Estate. They realised that by working as research coordinators, they would have an opportunity to speak to residents of the community and find fading memories of Macao. And so they took on the job, set out for the estate and soon discovered an office housing an enormous amount of furniture, gadgets and tools from times gone by. It was a treasure trove for the artists, and it would form their ambitious “Allegory of Dreams”, an exhibition now on display at the Venice Biennale.

Macao’s sole representatives, selected out of 24 proposals by 60 local artists, YiiMa’s “Allegory of Dreams” opened on 22 April at the prestigious Italian art and culture show and will run until 20 October. Divided into four sections – “Boat of Dreamers”, “Symbols of Dreams”, “Space of Dreams” and “Iao Hon Dynasty” – the exhibition questions what it means to be human today through photography, performance art, videos, and sculptures produced at several private and public locations across Macao.

Once again curated by Portuguese lawyer-turned-curator João Miguel Barros, the show reunites the three visionaries after their collaborative exhibition “(De)Construction of Memory”, a show held in Lisbon in 2019 that marked the 20th anniversary of Macao’s handover to China.

The result is a surrealist examination of past, present and future, with the artists appearing as angels and emperors hovering over real sites. Taken together, the series forges a connection between reality and dreams, and forces the audience to remember old Macao while envisioning its future.

Ung says that the duo intended to show Macao’s true colours. “The spirit of Macao, despite its small size, is inclusive and diverse,” he explains. “We see beautiful churches and temples co-existing harmoniously, such as St Paul’s Ruins sitting alongside Na Tcha Temple. That’s what makes Macao marvellous. Different racial groups can live here, including Filipinos, Indonesians, Portuguese and more.”

Symbolic metamorphoses

The exhibition is a perfect fit for the theme of this year’s Biennale, “The Milk of Dreams”. The theme was inspired by a book penned by British-born Mexican surrealist artist and writer Leonora Carrington (1917–2011), whose ethereal, transformed imagery invited viewers to embark on journeys to explore the human condition, femininity and mysticism.

“Allegory of Dreams” lingers on one key image: angels. The section “Symbols of Dreams” displays seven photographs taken in the shape of a Baroque church’s domed ceiling, mirroring the elaborate paintings that traditionally adorned them with visions of Paradise. In the exhibition, the paradisiacal sites, as it were, include old stores, a century-old martial arts hall and an office in the Iao Hon Estate. Each work is packed with objects that belong to the sites’ owners.

Such eclectic images fascinate Chan. “At a glimpse, you may find the sites very messy. But I like such dominating power,” he says. “In a good photographic hand, the whole picture can unveil many objects that are worth pondering.”

On the other hand, Ung, a renowned art scholar, prefers to look at the meanings behind the individual objects. “Each object carries the owner’s emotion. How come each place has so much stuff? There must be a reason why the owners keep the objects,” he says. “We capture the historical context these objects convey through photography.”

The duo, depicted as angels, appear to fly near the ceilings in each photograph. If that sounds like it must have been strenuous, it was. The two had to stand on a ladder to frame the shots. To create a greater three-dimensional effect, one would be held aloft with a rope while he posed in the air. Then, they would move the ladder and the other would take his turn posing mid-air.

Chan took the photos with a mobile phone that was connected to a camera set on the floor. In post-production, Chan cut the photographs in half and removed the ladder from the frames. He insists that they never add additional effects or objects into the photographs but only remove unnecessary objects – all part of a highly involved process.

He also recalls how challenging it was to shoot within such small sites. According to Ung, their props were improvised, chosen because they held significance to their owners.

As for poses, the two drew inspiration from Western art, as well as their database of photographs and press clippings.

To capture Macao’s cultural diversity, the duo selected their sites according to their historical context. The photographic work titled “Kit Yee Tong”, for example, was shot at a century-old martial arts hall which now teaches the traditional lion dance to local people. “Macao is a dazzling city, but it [Kit Yee Tong] keeps the traditional culture [alive]. Their students and members are volunteers, and some of them are very young,” says Chan.

In the middle of this section, visitors will find a 400-page book, the “Book of Heaven”. The volume consists of over 300 photographic works and complements their idea of ‘performance art documentation’. If you can’t make it to Venice, rest assured: there’s a smaller copy currently on display at the Macao Museum of Art.

Ironic inequities

Another highlight is “Iao Hon Dynasty”, a part of the exhibition that features two enormous photographs, each nearly 1.2 metres wide and 2.3 metres high, portraying the duo YiiMa as emperors on their thrones in the “Office in Iao Hon”, the name they’ve given the humble setting in which they staged their shots.

The works juxtapose royalty with the working class community, an ironic image meant to poke fun at human pride. The royal imagery was inspired by historical monarchs such as the emperors Qianlong of the Qing dynasty and Napoleon Bonaparte, with the two wearing replicas of luxury shoes used for cremation rites in traditional ceremonies. Gold leaf sheets pasted on their faces symbolise human pride.

“Gilding some sculptures … creates a distance between the sculptures and viewers. By idolising two fake kings [in our work], we want to generate a feigned sublimity and idolisation.”

Adding new dimensions with different media

Video installations enhance the message and lead viewers to think more deeply about human nature. The four-channel video piece “Space of Dreams”, for instance, turns to Greek philosopher Aristotle to grapple with some of life’s pressing questions. Inspired by Aristotle’s seminal work, The Four Causes – four fundamental types of answers to the question “Why?” – the piece seeks to understand how inequities form.

“We’re exploring various [artistic] expressions. The videos are kinetic and force the viewers to follow us and look at the objects of the two emperors in ‘Iao Hon Dynasty’,” explains Ung. “We’ve applied Aristotle’s thoughts on humans to ask, ‘How can a person become an emperor?’ In fact, it’s because of one’s greed.”

Ung adds that this piece adheres to one of the Biennale’s focuses: to explore the relationship between people and technology. “Humans put themselves in the centre of the universe. Logic and science, generally celebrated by humans, actually diverge from nature. Human relationship with science is contradictory.”

Rethinking the current moment

The use of the colour gold takes on special meaning in the visually compelling sculpture “Boat of Dreamers”. Two angels – modelled to resemble the artists – seem to ponder something excruciating as they sit atop a golden globe situated in a boat. The boat is placed on a stand made from old ship wood, collected at a wood recycling plant for fishing boats in the Zhongshan area.

The sculpture evokes an image of angels embarking on a journey from Macao. This piece opens “Allegory of Dreams”, setting the tone for the philosophical questions the exhibition poses.

“The ship wood implies a connection between Macao and Venice, both of which had a rich history of navigation. When creating this sculpture, we considered its visual impact, including how the viewers look at it,” says Chan.

“The boat has holes, so you may wonder whether the angels are contemplating something very worrying,” adds Ung. “Dreams are beautiful, aren’t they? But will you give them up once you find out they are not? Humans always feel anxious, disappointed and discouraged when faced with the unknown.”

By using a rich variety of different media, gleefully improvising and revisiting old Macao, the art duo YiiMa might help Macao residents find new strength within their city. For more than two years, routine life has included lockdown, masks, quarantines, vaccinations, infections and more. Humans have faced the unknown. “Allegory of Dreams”, together with the Venice Biennale, does not imply that art can give us salvation, but rather that it might help us all find the courage to face pressing issues together and rediscover the joy of being alive.