The Portuguese may have brought azulejo tiles to Macao, but the city has made this ancient art form its own.

Azulejos: You might not recognise the name, but you’ll know them when you see them. Walk around Macao and you will find these glazed ceramic tiles decorating alleyways, foundations, schools, churches and flowering courtyards. Most often a combination of blue, white and yellow, the tiles depict graceful palm fronds, strapping Portuguese heroes, biblical scenes amongst others.

Since the Portuguese introduced azulejos more than 400 years ago, they have since become an iconic part of Macao’s architecture and culture. In fact, in August 2020, the Cultural Affairs Bureau of Macao added Portuguese-style tile making and painting to its growing inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Macao.

To better understand how they became a symbol of Macao’s multicultural past, we take a look at the evolution of azulejos and the story behind this beautiful local craft.

From Babylon to Macao

Derived from the term for “polished stones” in Arabic, azulejos – particularly the blue, white or yellow varieties – have become synonymous with Portugal. But the use of glazed and decorative ceramic tiles actually stretches back to ancient Assyria and Babylon – two of the most prominent Mesopotamian empires.

These ancient worlds were filled with colour. Archeologists have discovered countless decorated tiles and bricks on the walls of ancient Assyrian palaces, as well as the Gate of Ishtar, built in 575 BC at the entrance to Babylon; the Step Pyramid of Djoser, built in 2630 BC in Egypt; and the 6th-century Blue Mosque in Turkey.

In empires where Islamic culture flourished, geometric-patterned wall tiles served as important elements of artistic and religious expression. Islamic potters developed lustre tiles for palaces, mosques, and holy shrines, which gave these buildings a distinctive iridescent finish.

In the 8th century CE, the Moors brought Islamic mosaic and tile art to the Iberian Peninsula when they settled in the area. But it wasn’t until the 1500s, when King Manuel I of Portugal visited the Alhambra palace in Grenada, in southern Spain, that the Portuguese adopted this style of tile work. After falling in love with the palace’s dazzling geometric and colourful ceramic tiles, the ruler imported azulejos from Seville, a Spanish city west of Grenada, to decorate the “Arab Room” in his palace in Sintra, Portugal.

Azulejos as we know them today took shape during two major historical periods: the Reconquista, a 770-year-long series of civil wars between Christians and Muslims, and the Italian Renaissance.

After Christian forces wrestled control of the Iberian Peninsula from the Moors in the 15th century, tile painters began painting animals and humans (formerly banned by Islamic law), historical and cultural events, religious imagery, flowers, fruit, and birds.

Meanwhile, in Italy, the technique of majolica – tin-glazed pottery – made it possible to paint directly on the tiles. This made it easier for artists to depict more complex designs, and Portuguese tilers quickly picked up the skill. The Azulejos evolved from an almost industrial repetition of patterns to artistic creations.

Not long after the majolica technique emerged, Portuguese tile artists began experimenting with white-and-cobalt blue patterns inspired by Ming dynasty Chinese porcelain. After Portuguese aristocracy commissioned ornamental, blue-and-white tile designs for palaces and churches in the 17th century, the bicoloured style gained widespread popularity.

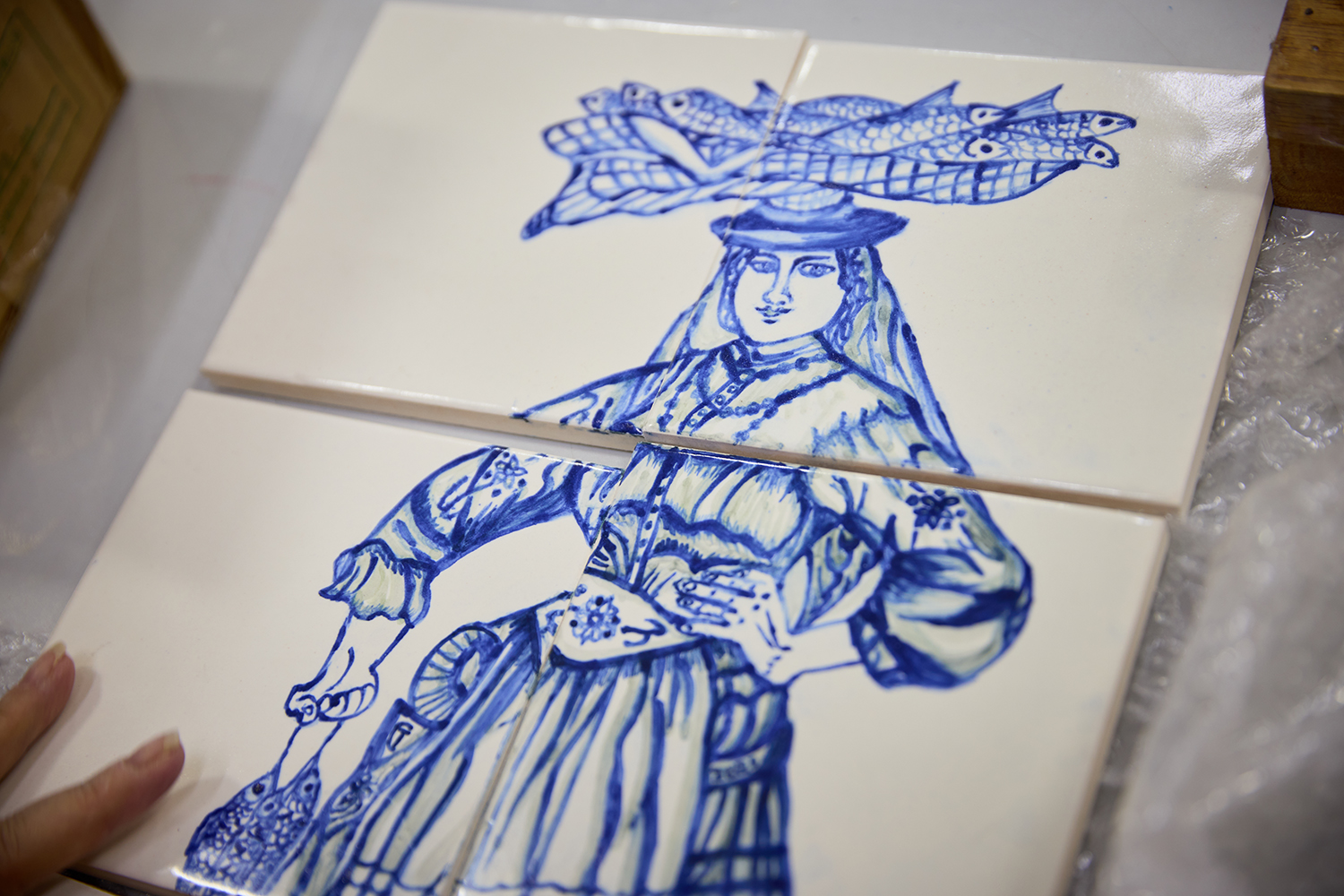

A particular style of azulejos that is unique to Portugal began to appear around the 18th century: figuras de convite, or invitation figures. These ornate life-size figures – generally of footmen, noblemen or finely dressed women – decorate the staircase landings of courtyards or entrance halls, welcoming guests inside.

Azulejos in Macao

The ceramic tiles that had been used for centuries to decorate buildings and public areas in Portugal spread to its colonies and settlements, and Macao was no exception. When the Portuguese settled in the territory, they introduced their food, religion, architecture, and of course, azulejos, which now form a very important part of the visual and cultural fabric of the city.

Scattered throughout, the azulejos of Macao can be found in churches, in courtyards, and various building façades – even street names are printed on signs that resemble the blue-and-white tile design.

Over the past four centuries, Macao has embraced these tiles as part of local culture. From the techniques to the motifs, they have come to symbolise the city’s Chinese and Portuguese characteristics. They also serve as an artistic embodiment of the peaceful coexistence between Chinese and Portuguese cultures.

At Casa de Portugal (CPM) – a non-profit association that aims to promote and preserve Portuguese culture in Macao – a large studio welcomes people of all ages and skill levels to join workshops focusing on the creative industries, including painting azulejos.

Workshop instructor José Matos, who joined the association in December 2019, says it’s a place for people to connect with Portuguese culture. “This Portuguese style of painting on tiles is so symbolic, and that’s what people here really enjoy,” he says. “Azulejos have become a part of Macao and its history. It’s important that we keep the art alive.”

In the beginner’s course, students learn to draw pictures in the majolica style – birds, fruits and flowers – and then paint on the tiles, which is harder than it sounds. When bathed in a glaze of silica, water, lead and tin oxide, the tile absorbs the water while the powder forms a thin layer covering the tile’s surface. “It’s very different than painting on paper,” says Matos. “When you paint on paper, you have much more control. But when you are painting azulejos, you are painting on a powder, and it is difficult to control.”

While students come and go, some keep returning to delve deeper into the art. For example, mother Paula Bernardino, daughter Sara Figueira, and fellow student Teresa Cheong have been attending classes at CPM for more than a decade. They also participate in fairs and markets to showcase their work.

“We love Portuguese tradition – that’s why we have come here almost every day for the past 10 years,” says Figueira. “We have taken all kinds of ceramic classes, but azulejos are our passion. We are Portuguese and we need to remember our culture. Painting tiles is part of who we are.”

“Painting tiles takes patience,” she continues. “You need to practice, practice, practice.”

For Bernardino, all that practice paid off in June, when her masterpiece of a full-size caryatid – a female figure that doubles as a column or pillar – was featured at the Casa de Portugal’s “Didactic Exhibition of the Portuguese Azulejo”. With the support of Macao Foundation, the exhibition was held from 8 to 20 June to commemorate the “June Month of Portugal in the MSAR”. It was also dedicated to the art of tile-making, with an aim to increase awareness about azulejo techniques and artistic expressions.

Curated by Matos and Paulo Valentim, an azulejo master, the exhibition took place at Lou Lim Ieoc Garden, and welcomed over 4,000 visitors. “Our initial plan was to feature works from masters in Portugal, but of course with the pandemic, that was not possible,” says Matos. “A lot of works have been made [at the workshop] over the past 10 years, so we were able to showcase different techniques and examples.

Everyone who attends classes here wants to know about azulejos and how they are made. This exhibition was a simple but perfect way of explaining it.”

Ten years may seem a long time to some, but for artists creating azulejos, it’s just the beginning of a lifelong passion. “Once you start painting the tiles, you cannot stop – it’s very addictive,” says Figueira. “It’s nice to see azulejos around Macao, but really, we should have much, much more, and not just printed tiles, but hand-painted, unique pieces. They add so much culture and make the city richer.”

The azulejos found around Macao are more than just beautiful pieces of artwork. They communicate the city’s history and heritage, as well as illustrate the significance of a Portuguese presence in Macao and the city’s development. “It is so important for us to continue this tradition,” Figueira says. “If we don’t, it will die out.”