It’s tempting to write tai chi off as a healthy hobby for the elderly, who are undoubtedly its most visible practitioners. You see them in public parks, perfectly poised. Their posture is upright, their faces serene. Their hands move like slow-motion doves, sometimes wielding swords or sabres. But this ancient martial art is more than a way to stave off arthritis. Unlike its more combative cousin Shaolin kung fu, tai chi is considered an internal martial arts form prioritising a meditative synchronisation of mind, body and spirit. Practitioners are urged to focus on their qi, or energy flow.

A Taoist monk named Zhang San Feng is widely believed to have formalised its practice in the 13th century, though tai chi’s roots date even further back. Different styles have evolved over time and there are currently five recognised schools of tai chi: Chen, Yang, Wu, Hao and Sun, each named after its founder. While their moves and forms differ, their basic philosophy is the same: balancing yin and yang. The schools share an emphasis on controlled breathing and movement, and yielding to and redirecting incoming blows, rather than meeting attacks with opposing force.

Tai chi was taught behind closed doors for centuries, and didn’t start spreading throughout China until the early 20th century. Masters from the north – where tai chi was more widely practised – started moving south and influencing nanquan martial artists, whose practice involved short-range hitting with fists. As martial arts clubs began organising more demonstrations and combats, tai chi’s popularity in China’s south increased. Wu-style’s founder’s grandson, Wu Kung-i, even relocated the Wu school’s headquarters to Hong Kong.

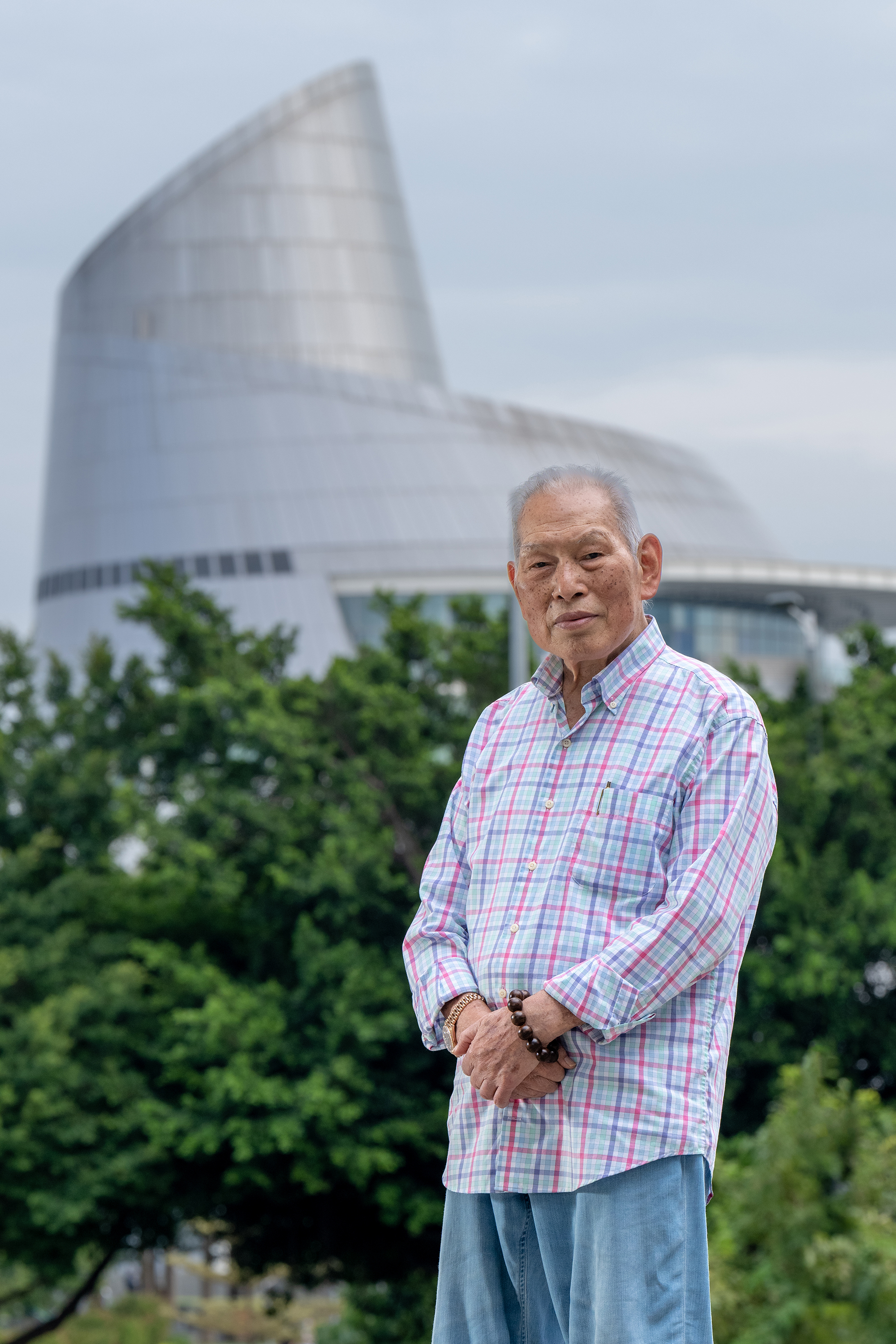

A consequential battle took place in January, 1954: Wu-style tai chi master Wu Kung-i versus Chan Hak Fu, Macao’s master of white crane quan (a fist-fighting technique that imitates a bird’s pecking beak and flapping wings). The combat took place in a special ring built atop Macao’s Estoril Swimming Pool and drew intense media attention. Among the many excited onlookers was a 9-year-old boy named Lei Man Iam. Decades later, he’d become the president of the Association of Martial Arts Masters of Macau and a champion of Chen-style tai chi, which at that time did not exist in Macao.

Coming up in the golden era

Lei was first exposed to martial arts through his grandfather, a vegetable farmer from northern Macao, who taught him some basic kung fu moves for self-defence. When his school began offering free kung fu classes, an eager Lei signed up immediately. “My first martial arts teacher called his style of kung fu ‘Choy Li Fut’ [a martial arts style combining skills from southern and northern traditions],” remembers Lei. “He didn’t say much about its history, and we never dared to ask. We practised what we were told, such as fist work, footwork, weapon usage and combat skills. It was very practical.”

After a few years, 14-year-old Lei was selected to be his teacher’s assistant. Two years later, in 1962, he started taking advanced Choy Li Fut lessons with a local master named Man Chong Kong. Master Man explained the practice’s theory, history and stylistic contexts, and Lei quickly excelled under his guidance. But opportunities to test out his talents were few and far between. The annual National Day celebration was the only time Macao’s martial artists got a chance to display their prowess.

Lei became a Choy Li Fut teacher himself in 1964. Then came Bruce Lee: the American-Hong Kong martial arts maestro made traditional Chinese styles of defence (wushu in Chinese) cool around the world through TV and film productions like The Green Hornet (1967), The Big Boss (1971) and Fists of Fury (1972). Macao was not immune, and Lei remembers wannabe Bruce Lees queuing up outside his door to learn Choy Li Fut in the early 1970s.

In the midst of this golden era for martial arts, a senior master advised Lei to switch his speciality to tai chi. Lei – in his late 20s at the time – recalls feeling surprised, because meditative tai chi is very different from “powerful and fast” Choy Li Fut. “Back then, the most common tai chi practices were usually Yang and Wu-styles, which were very slow,” he says. “The master said I might not be able to keep up the intense and high-speed practice [of Choy Li Fut] when I get old, so tai chi would be a great alternative to sustain my martial arts career.”

Chen-style tai chi enters Macao

Lei did not take up tai chi there and then because its slowness somehow made it seem like a lesser option. But in 1979, two transformational experiences convinced him tai chi was in fact his calling. That March, Lei was part of a martial arts exchange programme in Foshan, Guangdong province, where he met tai chi master Lei Hui Quan. The pair began secret training sessions. Why secret? To spare Lei’s ego: “If I failed, it wouldn’t be embarrassing,” he admits wryly.

Then, in May, Lei joined the first National Wushu Observation Conference. Held in Nanning, Guangxi province, the conference allowed martial artists of various styles to demonstrate their skills and interact with each other. It opened Lei’s eyes to dozens of martial arts he’d never even heard of. “I felt like a frog at the bottom of a well,” he recalls. It was his first time witnessing the more vigorous Chen-style of tai chi, which at the conference was performed by an 80-year-old woman with a sabre. He remembers her “exhibiting immense power”. That elderly woman and other Chen-style tai chi masters he met at the conference cured him of his stereotype.

After those trips, Lei spent a decade seeking tutelage from Chen-style tai chi masters, alongside teaching and practising Choy Li Fut. One master was Chen Xiaowang from Chen Village, where the school originated. He was the 19th generation of his family involved in martial arts. Another was Chen-style grandmaster Feng Zhiqiang, who strongly influenced the way Lei now teaches students himself. “I was so excited to get trained by Master Feng,” he says. “We [Lei and his peers] always talked about his greatness.”

In 1982, Lei dropped Choy Li Fut to fully concentrate on practising and teaching tai chi. He performed Chen-style tai chi competitively for the first time in 1987, at the inaugural Macau Wushu Championships, and won gold. He ended up winning it again and again, over seven successive years.

But Macao’s tai chi community were still wary of the Chen way, claiming it had more in common with Choy Li Fut than the softer Yang and Wu schools they were familiar with. Lei took their criticism on the chin: “Chen-style tai chi has taught me composure. I believed I could prove myself if I keep doing my best,” he says. That perseverance paid off. Today, the Chen-style is as popular in Macao as Yang and Wu. When the Macao government began offering free tai chi classes in the early 1990s, all three schools were taught.

Martial arts in Macao today

According to Lei, the number of people practising tai chi in Macao is neither increasing or decreasing. But that’s not the case for other martial arts. Lei says their popularity is dwindling, and that instructors can no longer make a living through teaching alone. One reason for this could be lack of awareness, Lei suggests. There are so many different styles that it’s hard to unify martial arts and market them to a targeted audience. Another reason is that it’s mainly teenagers who take up the sport, and they tend to lose interest and/or run out of time once they start university or jobs. Tai chi’s all-ages accessibility as well as its visibility, being practised in public parks, surely help account for its enduring popularity.

Today, a revered martial arts master in his late 70s, Lei starts his day before dawn with two hours of Chen-style tai chi practice at home. He continues to teach in one-on-one and group classes. While Lei’s earliest tai chi students were retired people and housewives, he says the discipline is increasingly popular with a younger crowd: “There was surely a misunderstanding of tai chi. People assumed it was for old men, but in fact it suits everybody.” Lei stopped counting students after his 10,000th.

His lessons typically last over two hours. He’ll start with a warm-up: running, stretching, and zhan zhuang (which means ‘standing like a tree’). Then senior students guide beginners in standard sets of tai chi movements that they’ve learned in previous lessons. All together, they repeat a whole set of specifically Chen-style tai chi movements several times for Lei’s review. He circulates the class, offering advice for improvements.

Chen-style tai chi: powerful, elegant and calming

One of Lei’s students is Frederico So, a middle-aged civil servant. So was intrigued by the swords and sabres one of his colleagues carried to work each morning after her tai chi classes with Lei. He was already familiar with martial arts, having worshipped Bruce Lee and dabbled in wing chun as a youth. Inspired by his colleague’s passion, So decided to sign up with Lei – though not without some scepticism. “At first I considered tai chi as for the elderly, something I could pick up when I am old,” So says. His first class had him hooked, however: “It was strenuous, requiring much more energy than I had expected.” ‘Silk-reeling’ is a favourite Chen-style movement of So’s, its name derived from the twisting and spiralling movements a silkworm larva makes as it wraps itself into its cocoon. “This is coupling strength and gentleness, and I’ve fallen in love with that,” says So. But most useful of all, his six years of tai chi have taught him the benefits of mindfulness. “Through Master Lei’s tai chi, I’ve learned how to relax. It has influenced my view of life.”

So has become a Chen-style tai chi evangelist and readily spreads the word among friends. One friend ended up encouraging her daughter, 22-year-old Carolina Rego, to take up the martial art form for its health benefits. Rego, a law student who already had some experience with Japanese jōdō (a staff-wielding martial art), first took Lei’s class in 2021. She says it has helped heal injuries sustained through her previous martial arts practice.

“You may think of elderly women sweeping their hands when it comes to tai chi. But it actually has power and speed and elegance,” Rego enthuses. “It also brings me calmness. I used to be quick-tempered, but now I feel composed every day.” After one year of Chen-style tai chi practice, Rego earned third place in the junior women’s session of the Macao Tai Chi and Weapon Championships, held by the Wushu General Association of Macau.

A more experienced older student of Lei’s is 70-year-old Connie Zhang, who says an “accidental encounter” led her to the Chen school in 2016. She was drawn to tai chi through her interest in traditional Chinese culture, decided to take lessons at the Macao Polytechnic University Seniors Academy, and picked Lei’s class at random. “I have been active in sports since childhood, and as I am getting old I thought tai chi would be a good alternative,” Zhang says.

The practice has changed Zhang’s life: “Tai chi is a deep school of knowledge,” she says. “I’ve learned to be composed when probing life problems. Especially at my age, when we come across many life problems, being composed surely helps.”

Lei says he’s proud of his role in making the “gentle strength” more accessible to Macao people. For more than four decades, he has championed the Chen school of his sport and earned recognition both locally and globally. “Tai chi brings many health benefits, from managing the symptoms of chronic diseases, to helping heal old injuries, to improving mental health – I can see it in my students,” he says.

“I feel grateful and delighted to spread the word of Chen-style tai chi. It didn’t exist in Macao, but now many people are intrigued and involved… it amazes me.”