On 19 December 1993, the New York Times Magazine splashed an unsettling painting across its cover. This distorted, grimacing face made its Chinese painter, Fang Lijun, famous. The same year, Fang was one of 10 Chinese artists featured at the prestigious Venice Biennale. He’d captured the zeitgeist at just 30 years old.

Beijing-based Fang is part of an artistic movement known as Cynical Realism, which emerged in the early 1990s in response to socio-political changes happening across China. Cynical Realists, including the artists Yue Minjun, Zhang Peili, Wenda Gu, Wu Shanzhuan and Xu Bing, are known for using dark humour to express their disillusionment and challenge societal norms.

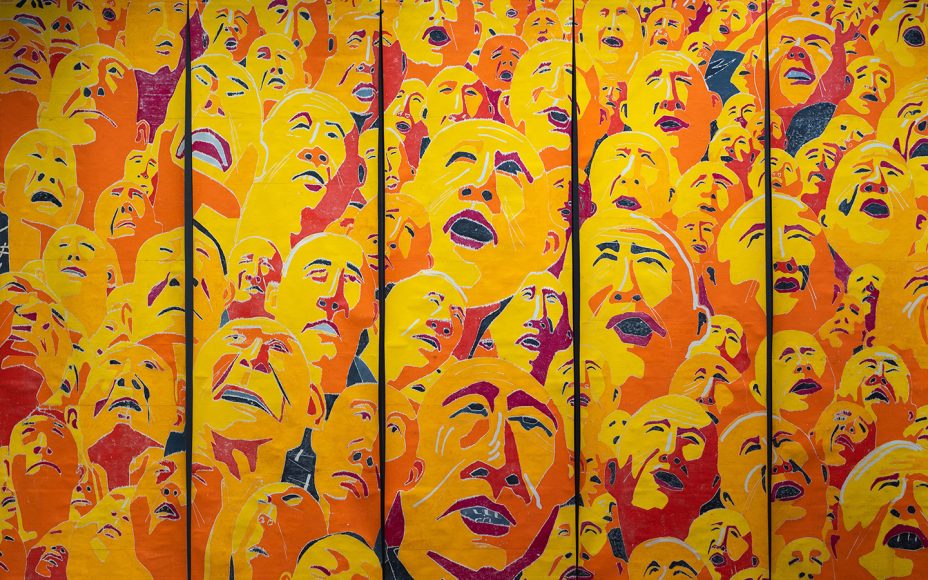

The movement drew significant interest throughout the 1990s and 2000s, both internationally and within China. Today, versions of Fang’s iconic 2003 work, SARS (later named Untitled), are held by Paris’ Centre Pompidou, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Hong Kong’s M+ Sigg Collection and the Guangdong Museum of Art. Each version is a vibrant set of seven four-metre-high panels – really unfurled paper scrolls – printed with flame-hued faces using woodblocks.

Guangdong’s panels were on loan to the Macao Museum of Art (MAM) for a special exhibition titled, “Fang Lijun: The Light of Dust”. The exhibition was an ambitious retrospective of Fang’s work over the past four decades, in mediums spanning ceramics, sculptures, oil, woodblock printing, and ink.

An artist’s journey

Fang Lijun was born in Handan, Hebei Province, to a wealthy family in 1963. An art teacher introduced him to Li Xianting, the respected art critic who named the movement Fang has become synonymous with: Cynical Realism.

Fang’s artistic education was broad. He was exposed to watercolours, oil painting and ink from a young age and went on to study ceramics at the Hebei Light Industry Technology school. Then he changed tack, enrolling at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts to specialise in printmaking. In the early ‘90s, Fang lived in the Yuanmingyuan Artists’ Village; a place where freedom of expression was valued over financial gain.

In a 2020 collection of Fang’s essays and interviews, titled What About Art, Fang recalls rejecting the thriving 1990s art market. “[It] felt reckless to sell my works at amazing prices,” the artist wrote. “If I went on like [that], I’d become an artist who chased after the market and lost my creativity.”

For his Untitled panels, Fang described his intention to create something impractically huge – in a style that Chinese art buyers weren’t particularly interested in at the time. The fact that the piece ended up being purchased almost immediately was unexpected, he wrote. As was its influence in popularising woodblock printing in China.

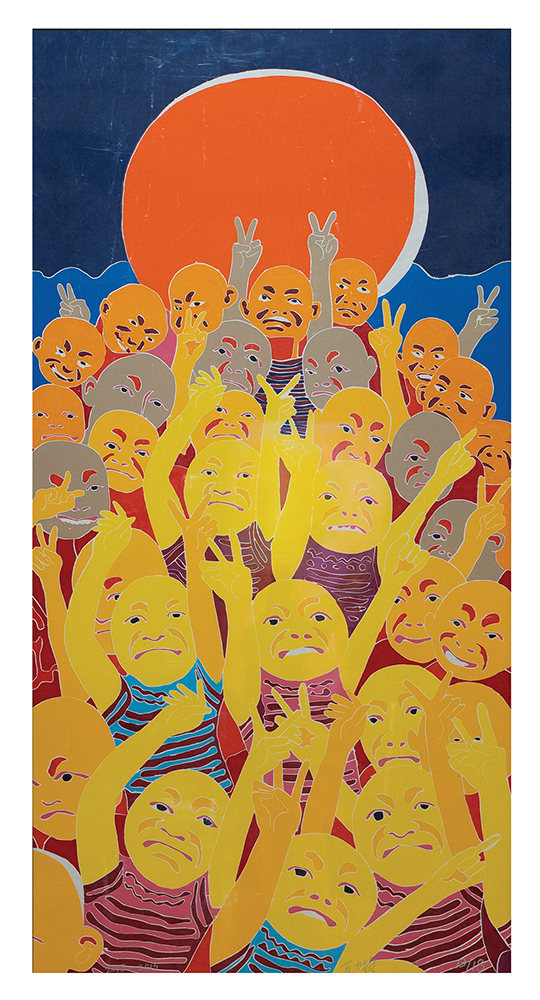

Fang Lijun’s ironic subject matter, bold colour palette, and humour have made him one of China’s most iconic contemporary artists. He is best known for his recurring bald figures, who appear to gape, or grimace at nothing – as seen in both the New York Times Magazine cover and Untitled.

Friendship, pain and water

Luo Yi curated MAM’s Fang Lijun exhibition and has edited several of the artists’ books. She points out that most of Fang’s subjects were depicted anonymously until quite recently. “From 2018 or 2019, you can tell the figures’ identities from his paintings,” she says. “In the past, he didn’t focus on that.”

Social media – particularly, the rise of selfie culture – sparked Fang’s interest in capturing existent people, in an identifiable way, says Luo. Smartphone’s beautifying apps tendency to make selfie subjects pretty much unrecognisable inspired the artist to “unfold [people’s] real selves, which is their most precious side,” she explains.

The Covid-19 pandemic adjusted Fang’s artistic focus again: towards human connection. Luo says his aim was to create stronger bonds with his friends through painting them. Indeed, friendship is a strong theme in Fang’s Macao exhibition; untitled ink-on-paper portraits of his friends are spread over an entire wall of the MAM. Luo says she placed deliberate gaps between portraits to encourage visitors to take photos alongside them. “Metaphorically, the audience became the artist’s friends,” she explains.

The content may have changed, but Fang’s artistic essence has remained constant throughout his career. “He never casts himself as a portraitist; he never attempts to depict a person realistically, but instead aims to express a feeling of pain,” says Luo. “For example, he once painted a friend who had a car crash. [Someone] asked Fang Lijun why the figure looked so pained. He answered, ‘Once you feel pain, you realise the preciousness of life.’”

Fang is a keen swimmer and often depicts water in his artwork. He’s painted drowning men and bald, bewildered babies who float over the ocean. One of his best-known works at M+ Sigg – 1995.2 (1995) – is of a bald figure facing the sea, his back to viewers. No one can tell how this figure feels.

“Water is very close to my understanding of human nature,” Fang Lijun once said, when discussing his 1998 work Lao Li is Swimming. “Water is liquid, not rule-bound. When you look at it, it changes. Sometimes you think it is very beautiful, very comfortable, but sometimes you think it is terrifying.”

At the MAM

Water features in a stand-out piece included in “The Light of Dust” – an ink-on-paper polyptych almost six metres wide, titled 2021. The work captures the rhythm of swimming, according to Luo. The curator describes it as a landmark achievement for its medium. In the history of Chinese ink art, portraits are seldom created in such a large size,” she says. “It requires a high level of skills and experience.”

The exhibition, which saw almost 30,000 visitors from March until early May, took three years to bring to life. The MAM’s exhibition coordinator, Tong Chong, says that pandemic uncertainty added time to the process. “We had to make a lot of adjustments, changes and reorganisations,” he notes. “In response to different prevention and control measures in various places, the exhibits were finally transported by sea, which takes longer than by land.”

Fang Lijun travelled to Macao for the exhibition’s opening event on 3 March, to meet with the city’s art lovers. While there, he discussed his artistic inspiration and explained that he’s never been one to paint traditionally pretty scenes and subjects. Tranquil lakes, bamboo forests, graceful birds perched in plum trees – these, and their ancient symbolism, are not for him. Rather, Fang’s bold, often surreal, sometimes jarring work has its own lexicon that’s heavily laden with social commentary and emotion. His use of repetition stands for conformity; his clouds for transcendent escapism. On the bald, human figures almost ubiquitous in his work, the artist speaks of people’s unique ability to inspire emotion. “All my feelings – happiness, anger and sadness – come from people,” he said.