Making tofu by hand is laborious. Just ask Lei Iat Wah, owner of the Inner Harbour restaurant Sopa de Fitas Ving Kei. He’s been crafting these creamy blocks of soybean goodness for the past 30 odd years – in much the same way his parents did over half a century ago.

Once the 65-year-old is finished preparing his tofu, he adds it into a range of different dishes, from noodle soups to fried meat with vegetables. Then he serves it up to his loyal customers. Sopa de fitas, the Portuguese words in the name of Lei’s small eatery, actually means ‘noodle soup’ (you see a lot of sopa de fitas around Macao). The Cantonese Ving Kei – a play on his father’s nickname – is what differentiates the restaurant from similar businesses.

But Ving Kei’s signature dish is not noodle soup. That honour belongs to hot and cold tofu puddings, known as dau fu fa in Cantonese. These pale desserts may look unassuming, but their delicate, melt-in-your-mouth textures and sweet syrup toppings have certainly helped put Sopa de Fitas Ving Kei on Macao’s culinary map.

From little things, big things grow

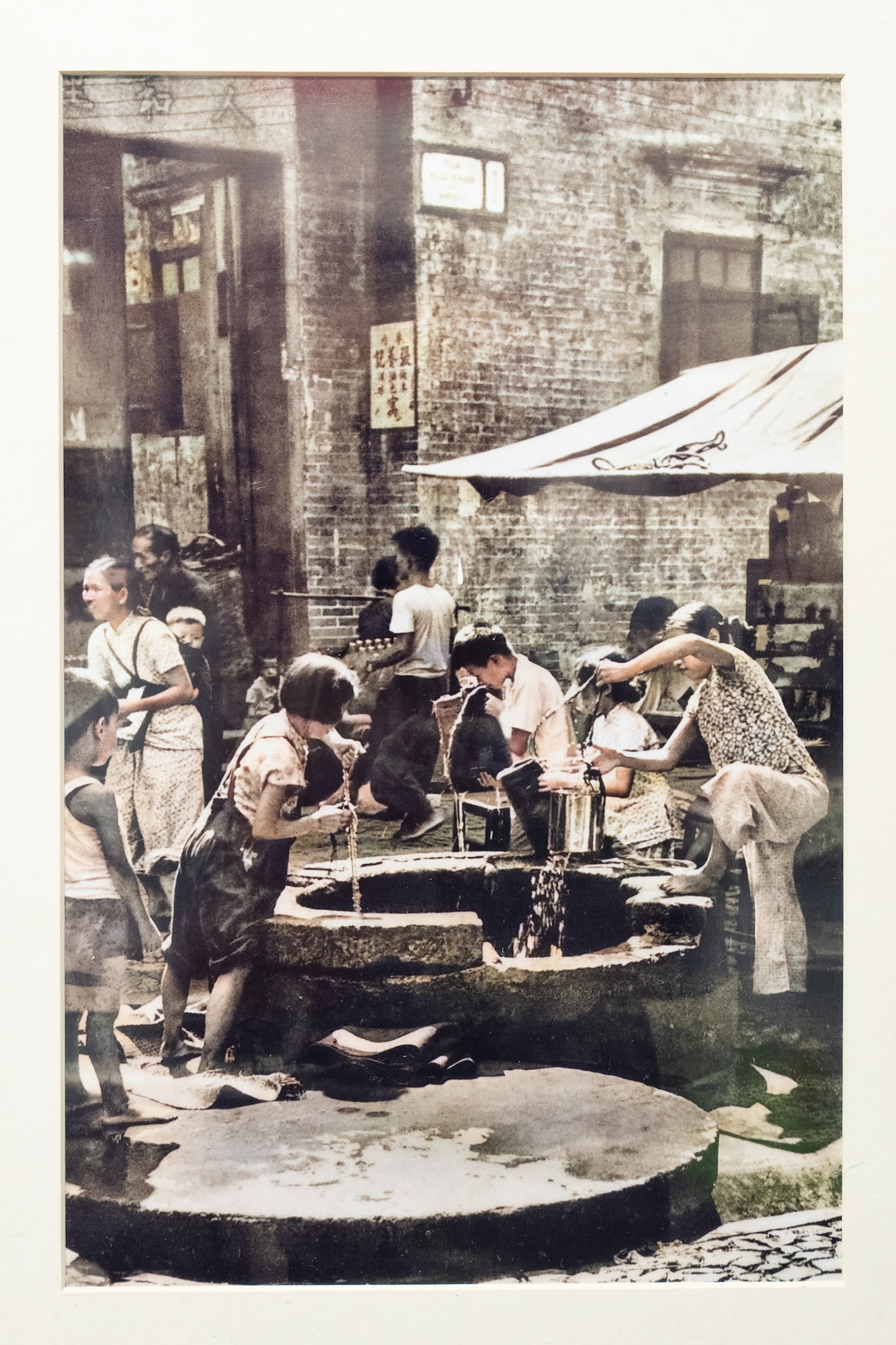

Lei’s parents, Lei Kuong Men and Tam Chao, started their culinary careers as hawkers, selling an assortment of food items in the Inner Harbour area (on the western shore of Macao Peninsula). Then, in the early 1960s, one of his father’s friends made a life-changing proposition.

“My dad had a friend who knew he could make tofu pudding,” Lei recalls. “He asked my dad if he wanted to be his own boss, making and selling tofu himself. At first, my dad didn’t have any money, so that friend paid for a special stone grinder [a key tool for making tofu] and gave it to my dad.”

Now with the means to produce their own tofu, which involves grinding soaked soybeans into a smooth paste, Lei’s parents proceeded to rent a small store. It was there they made their tofu puddings, to sell on foot along nearby streets. It was hard work, says Lei. Not only physically, but “there was no business when the weather was cold, as nobody would buy tofu pudding.”

His father decided to diversify the business. That’s when he began selling steaming bowls of tofu noodle soup (with vegetables and fish balls) for the cooler half of the year, and tofu puddings the rest of the time.

Back then, Lei’s parents sold their tofu from a heavy food cart they pushed along the streets. His older brother noticed the toll the cart was taking on his dad, so convinced the elder Lei to set up a permanent shop from inside their little tofu kitchen. He did, and that lasted for five or so years, until the building in which they rented was demolished. Ving Kei moved to its current location on Rua Da Tercena in 1973.

Lei Kuong Men retired exactly 10 years later. At the time, Lei and his three brothers weren’t sure about following in their father’s footsteps. They were already earning decent livings as taxi drivers and it didn’t seem worth exchanging those cushy jobs for what they knew to be back-breaking labour. But the senior Lei pushed them to return; if none of his sons would take on Ving Kei, the restaurant would lose its licence to operate. Unwilling to see their father’s life’s work undone, all four acquiesced.

They stuck at it together for a while, but each of Lei’s siblings eventually moved on to other things. “They just couldn’t handle it any longer,” says Lei. Tofu making is monotonous, and – at least the beginning – the family were working 16-hour days. His oldest brother immigrated to Canada in 1995 and the two younger ones stayed in Macao, but found other work. While they’re no longer permanent fixtures at Ving Kei, both still help Lei out from time to time.

A father’s ways – and president’s visit

As the remaining second-generation owner of Ving Kei, Lei takes pride in keeping many of his father’s tofu making techniques alive. For instance, he continues to cook the soybean paste over an open flame while other tofu cooks have switched to using electric stoves. “When customers eat our tofu, they will notice that it still has a little bit of a smoky flavour,” the restaurant owner remarks. “It’s not like the tofu heated using electricity, which is smooth and white, but completely lacking in flavour.”

Of course, Ving Kei has updated some aspects of the process. Especially when it comes to labour-saving innovations. That hefty stone grinder that first catalysed the business, for example, has been replaced with a more efficient electric one. “Before, when my father made tofu, it would take three hours to make a bucket-full,” Lei says. “Now it takes probably one hour.”

Since taking over the establishment, Lei has expanded the family business by opening up additional restaurants. Before the Covid-19 pandemic struck, there were five Sopa de Fitas Ving Kei branches around Macao. One closed due to staff shortages during the pandemic, but Lei plans to reopen it soon.

Ving Kei’s storied past includes several noteworthy highlights. One such moment was in 1999 when, Portugal’s then-president, Jorge Sampaio, paid the eatery a visit, just prior to Macao’s administrative handover to China that December. A framed photo of Sampaio and Lei shaking hands across Ving Kei’s kitchen counter adorns the restaurant’s wall, along with many other photographs documenting the shop’s rich history.

Recalling the high-profile meeting, Lei says that Ving Kei was selected over other restaurants in the area because its kitchen at the time was situated right on the roadside. This meant the Portuguese leader could greet its chef without violating security protocols by actually entering the premises.

While their encounter was brief, Lei feels “very fortunate” that it happened. “Because of that meeting, many people recognise me. Portuguese people know about me as well,” he says.

What the future holds

The tofu maker attributes his fitness to two daily habits: early morning swims, in the sea off Coloane’s coast, and singing karaoke after work. On the question of his retirement, Lei acknowledges that he cannot continue working indefinitely – and even admits that a heart condition is starting to slow him down. “At my age, I can do this for ten more years before I retire,” he says. “[But] I really have to retire. It’s not possible for me to say I don’t want to retire.”

As for who will take over the store once he stops grinding tofu, Lei makes it known that he does have a potential successor in mind – or “half a successor,” as he playfully calls this person. However, before revealing their identity, he wants to be sure they are up to the task. Ving Kei is a historic eatery, after all, and Lei needs his parents’ legacy to be in good hands.

What will he consider a mark of his successor’s success? “If they, like me, end up having people interview them,” Lei quips.