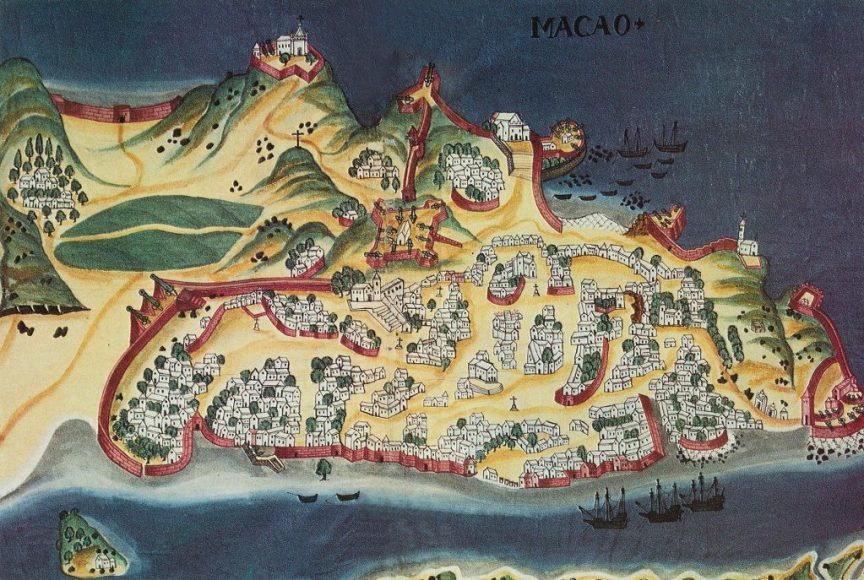

Precisely 400 years ago, a group of Macao residents, religious orders, slaves and Chinese citizens fended off a Dutch invasion of the Portuguese settlement, kept open the valuable trade route to Japan and reinforced relations with Chinese merchants. As a result of the victory, the King of Portugal appointed, in 1623, the first Governor of Macao, who consolidated the settlement’s defences to prevent future attacks from European nations, and Macao grew as a key trading hub in Asia.

In the first volume of Das Kapital, the only one of the three-part work published during his lifetime, Karl Marx recalls the history of the Dutch East India Company, the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC (1602-1799). Several times, he does so very critically.

The chapter on the “Genesis of the Industrial Capitalist” presents the VOC as the first modern capitalist company in history, denouncing the violence and massive exploitation that the Dutch trade organisation brought to Southeast Asia “dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.”

In consequence, the pages of Marx’s seminal critique of the political economy show no sympathy for the expansion of the Dutch commercial company in the Asian seas and ports where the so-called Portuguese eastern maritime empire had settled in the 16th century. Marx stresses that the history of Dutch rule in Asia was “one of the most extraordinary relations of treachery, bribery, massacre and meanness.”

The genius of this great 19th-century German philosopher proved these harsh words with a well-known historical example in the study of the decline of the Portuguese commercial presence in the Orient during the 17th century: the Dutch conquest of Malacca, the keystone to the riches of Southeast Asia.

According to Marx, to secure Malacca, the Dutch bribed the Portuguese governor to let them into the town in 1641. They hurried at once to his house and assassinated him to “abstain” from the payment of 80 reais (today around MOP 222,606), the price of his treason. “Wherever the VOC set foot,” Marx concluded, “devastation, and depopulation followed. Banjuwangi, a province of Java, in 1750 numbered over 80,000 inhabitants, in 1811, only 8,000. Sweet commerce!”

Unfortunately, Marx did not leave us any notes on Macao and its extraordinary historical importance in the intermediation of world trade from the late 16th century to the early 19th century. Therefore, our referential thinker ignored that the history of the VOC in the Eastern seas was not only one of conquest but also one that included dramatic setbacks. One of the most important was the failure of the Dutch mission in its attempt to invade and occupy Macao.

On 24 June 1622 – the Nativity of Saint John the Baptist in the Catholic Church’s liturgical calendar – the Dutch were utterly defeated after fierce naval attacks and deadly land clashes.

In this period, from 1580 to 1640, Portugal was ruled by Spanish kings in a dual monarchy system that became known as the Iberian Union. Soon, Portuguese cities, fortresses and trading posts throughout Asia, including Macao, inherited the usual enemies of the epochal Spanish empire: the English and the Dutch. It is worth remembering that the seven United Provinces of the Netherlands – which, with around a 1.5 million inhabitants, achieved independence through the revolt against Spain in 1581 – found in the creation of the VOC in 1602, and later, in 1621, of

the West India Company (GWC), the means to guarantee the abundant overseas commercial incomes able to consolidate their political, economic and military power.

In the first decades of the 17th century, the Dutch fleet reached 2,000 ships, at the time more than the combined navies of England and France. This powerful fleet brought professional navigators and maritime pilots to militias associating Dutch soldiers with mercenaries from the various geographies of Northern Europe united by the same Protestant opposition to Roman Catholicism and imperial Habsburg Spain.

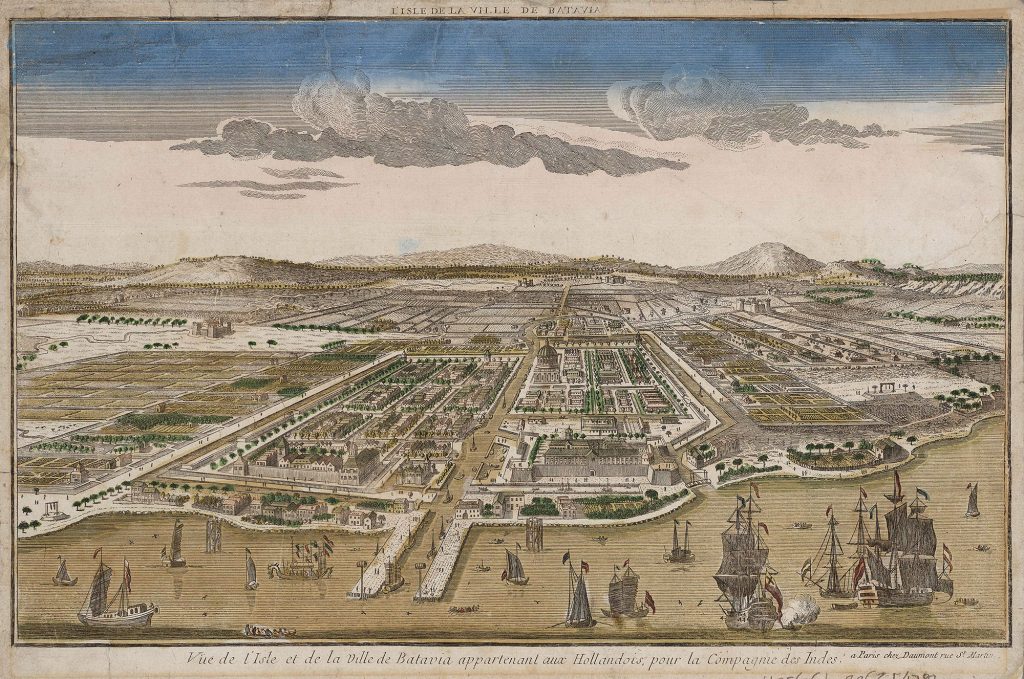

Since its inauguration as a modern, for-profit shared company, the VOC became not only a trade corporation but also a powerful instrument in the global maritime war against the Spanish Empire and the Iberian Union. Arriving in the East to compete with and conquer the Portuguese and Spanish settlements in the first decades of the 17th century, the VOC established its capital in Jayakarta, changing its name to Batavia (present-day Jakarta). After that, the city-port developed following the urban mercantile pattern of Amsterdam.

From Batavia, the VOC trade and military fleet quickly identified Macao as a central platform to access China and to attack Manila, the Spanish stronghold in the region with trade connections to New Spain (today Mexico and the Western United States). The Dutch had already attacked Portuguese trade ships near Macao in 1601, 1603 and 1607 but had never attempted to assault the Sino-Portuguese enclave.

In 1614, Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1587-1629) became director-general of all VOC trade factories, and later governor-general in Batavia from 1618 to 1629. Coen promoted a militant policy based on his sinister motto: Dispereert niet, ontsiet uwe vyanden niet (Do not despair, do not spare your enemy). Accordingly, Coen maintained that Portuguese and Spanish competition in the Eastern seas should be eliminated by force, a hard strategy that led to conflicts with VOC’s board of directors, the Heren (or ‘Gentlemen’) XVII, who generally preferred to achieve trade profits through less violent and costly adventures.

In 1621, Coen ordered a very expensive attack on the Banda Islands in Indonesia with the help of Japanese mercenaries aiming to control the archipelago’s prosperous nutmeg trade. The result was the massacre of the Bandanese: about 2,800 killed, 1,700 enslaved and 1,000 exiled in Batavia. The violent conquest resounded in the region, especially among the Portuguese and Spanish, who had trading factories in the Spice Islands.

Preparing to conquer Macao

In the same year, Coen started planning military action to conquer Macao, with three main commercial and political goals: controlling the Chinese junk trade to Batavia; removing the Portuguese from the Macao-Nagasaki silver trade, and building a robust naval base to attack the galleons running trade routes between Manila and Acapulco. The VOC had gathered information on Macao from several sources, including Portuguese documents collected in maritime attacks, interrogations of Chinese traders in Batavia and English reports. Coen believed that Macao wouldn’t be able to deflect an invasion led by a dozen strong-armed ships and a military force of 1,000 to 1,500 motivated men.

On 10 April 1622, Coen ordered a Batavian fleet to attack and occupy Macao. Captain Cornelis Reijersen, who kept a detailed journal of the expedition, set off with eight vessels loaded with modern artillery and 1,024 men. At the end of May, the fleet attacked two Portuguese trading vessels off the southern coast of modern-day Vietnam and received reinforcements of three other ships and 100 men.

On 20 June, the expedition reached a sheltered cove near the Taipa island, where two Dutch ships and two English vessels had previously tried without success to blockade Macao. However, Coen’s orders were clear: Reijersen could only accept English naval cooperation and must exclude them from the conquest and occupation of Macao, as well as all the spoils that would follow. The captain finally assembled 13 ships and a military force of 600 European soldiers, 100 Bandanese and dozens of Malay-Indonesian and Japanese mercenaries.

On 23 June, Reijersen and the other captains identified the best landing spot: the Cacilhas bay area in the outer harbour. In the evening, three Dutch ships engaged in an artillery fight against the bulwark of São Francisco at the entry to the inner harbour, but were damaged and retreated at night. At sunrise the next day, two other vessels restarted the attack on the São Francisco bastion only to withdraw again after heavy losses.

The land invasion began at Cacilhas beach as hundreds of attackers from 32 barges disembarked and came ashore. A small Portuguese force of around 150 men led by António Rodrigues Cavalinho, a prominent trader from the Macanese municipal elite, fired against the invaders, seriously hurting Reijersen, who had to be evacuated to his ship. Captain Hans Ruffijn took command of the Dutch and mercenary forces. The defenders (which consisted of many communities and nationalities in Macao) strategically lured the invaders to follow them up to the slopes of Guia Hill.

Here, in an area known as Fontinha (fount) due to its water springs, the Dutch forces were bombarded by artillery rained down from the under-construction Monte Fortress. Here, a patchwork of militiamen – Portuguese soldiers from the State of India, who had married and retired in Macao; Eurasian traders and their domestic servants; local and maritime Chinese; Spanish merchants and their Tagalog helpers plus hundreds of African slaves – repelled the invaders, immediately killing Captain Ruffijn and hundreds of Dutch soldiers and their mercenaries.

Dutch sources reported the loss of 180 men, hundreds of injured and most of their military equipment. Some Portuguese sources suggest that 300 Dutch were killed and hundreds more held captive, while Spanish documents from the Manila governor increased the number of deceased to 800.

The great defeat

Immediately after the heavy Dutch defeat, a process of textual representation of the victory circulated among the Portuguese, while the Dutch began a long process of justification of the failure, producing dozens of reports, including tough inquiries of the survivors. The VOC losses of both men and equipment were very high: for a profitable company, the Dutch defeat in Macao was not tolerable.

The Portuguese, meanwhile, produced two immediate representations of the event, with some divergences. The first, in Spanish titled Relación de la Vitoria, was printed in Lisbon in 1623. It was written by a Jesuit visitor of the missions, the Portuguese Father Jerónimo Rodrigues (1567-1628), who explained to European Catholic readers that the victory over the Dutch was a Jesuit feat since the missionaries had led the defence against the “heretical” invasion.

During this period, the Dominicans, who had settled in Macao by way of Manila and already criticised the Jesuit missionary accommodation strategies, produced their own interpretation of the events. The Portuguese Friar António do Rosário extolled the leadership of the city’s captain Lopo Sarmento de Carvalho, Captain-Major of the Japan Voyage, but his text remained a manuscript. Consequently, an account mobilised by the extensive world network of the Jesuit missionaries spread and was later considered the more authentic account of the Battle of 1622.

In the Jesuit chronicles of the 17th and 18th centuries, Father Manuel Xavier provided a different account, celebrating a convenient hero: the Italian Father Giacomo Rho (1593-1638) had fired a straight cannon shot from Monte Fortress; in some versions, the story holds that he destroyed the Dutch ammunition carrier, while in others his shot exploded the admiral Dutch ship, securing the victory.

Dutch VOC sources, including Reijersen’s journal, tell a different version. Since round numbers in these accounts are not exact figures but rather loose estimates used to express “many”, the Dutch documents based on several witness accounts decreased the size of their forces and increased the number of Macao defenders. The sources agree that there were very few Portuguese fighters. The Dutch were mainly attacked by hundreds of African slaves, who did not fight as European “gentlemen” but rather slaughtered the Dutch soldiers, behaving like “savages”. Some documents from the VOC archives even suggest that the Portuguese had purposely drugged their slaves, who barbarically killed and beheaded the surprised Dutch officials and soldiers. All the witnesses questioned by VOC agents agreed that a European army couldn’t oppose the animalistic brutality of the hundreds of slaves who outnumbered the Dutch forces.

The Portuguese sources only mention the role of the cafres (‘kaffirs’ in English is a derogatory term for a black African), without any special emphasis or figures. However, several accounts mention that many slave owners immediately freed their slaves after the victory. The “Portuguese” representations, written in Castilian, however, agree that the slaves beheaded many Dutch, which was interpreted as a kind of memory of the day Saint John the Baptist was beheaded. Civil and religious authorities in the following years concurred to make 24 June the city’s day and observant Catholic holiday in honour of the miraculous intercession of the saint.

Memories of foreigners who visited Macao in the years following the victory described the festivities of that day, including a devotional pilgrimage to a stone cross erected on the site of the Fontinha and even theatrical performances by children who studied with the Jesuits, featuring miniature boats and war scenarios depicting the great victory.

Much later, in 1871, the Leal Senado, the seat of the Macao government at the time, erected a public monument commemorating the battle. A column surmounted by the Portuguese royal arms displays a large inscription on the stone body that summarises the victory, but not without a bit of manipulation. Dictated by the growing anti-British nationalism of the Portuguese commercial bourgeoisie, who, in the case of Macao, wrongly accused the British colony of Hong Kong to be the primary cause of the economic decline of the Portuguese-Chinese city, Dutch Captain Cornelis Reijersen is engraved as “Roggers”.

The role of Mozambican slaves

For a historian researching the battle of 24 June 1622, rigour forces us to emphasise that the invading Dutch forces could not have been defeated without the mobilisation of the hundreds of African slaves in the enclave. Most were Macuas and Macondes, ethnic groups native to modern-day northern Mozambique and neighbouring nations, brought by the slave boats from the “carreira da Índia” to Goa, Malacca and Macao.

In the early 1600s, there were already 2,000 African slaves in Malacca and 1,000 in Macao. At the time, their only prospect of a tolerable life was to identify themselves as closely as they could with the wishes of their Portuguese masters. In Macao, these African slaves constituted the private militias of wealthy Portuguese and Eurasian merchants; did the heaviest work, from artillery foundries to bakeries; and were diligent domestic servants, providing water to their owners’ houses and emptying their waste each day.

Traditional history has generally forgotten these communities and praised the more powerful classes and their dominant heroes. Still, the very rich and capitalist VOC has fully documented that it lost the battle of Macao in 1622 at the hands of the brave, unexpected militiamen: the African slaves who protected the city.