TEXT Michael Lin and Perry Wong

From 2010 to 2015, Shenzhen’s GDP grew at a rate of 79 per cent. This year, Shenzhen’s GDP is expected to reach US$350 billion, surpassing the projected US$345 billion GDP of neighbouring Hong Kong.

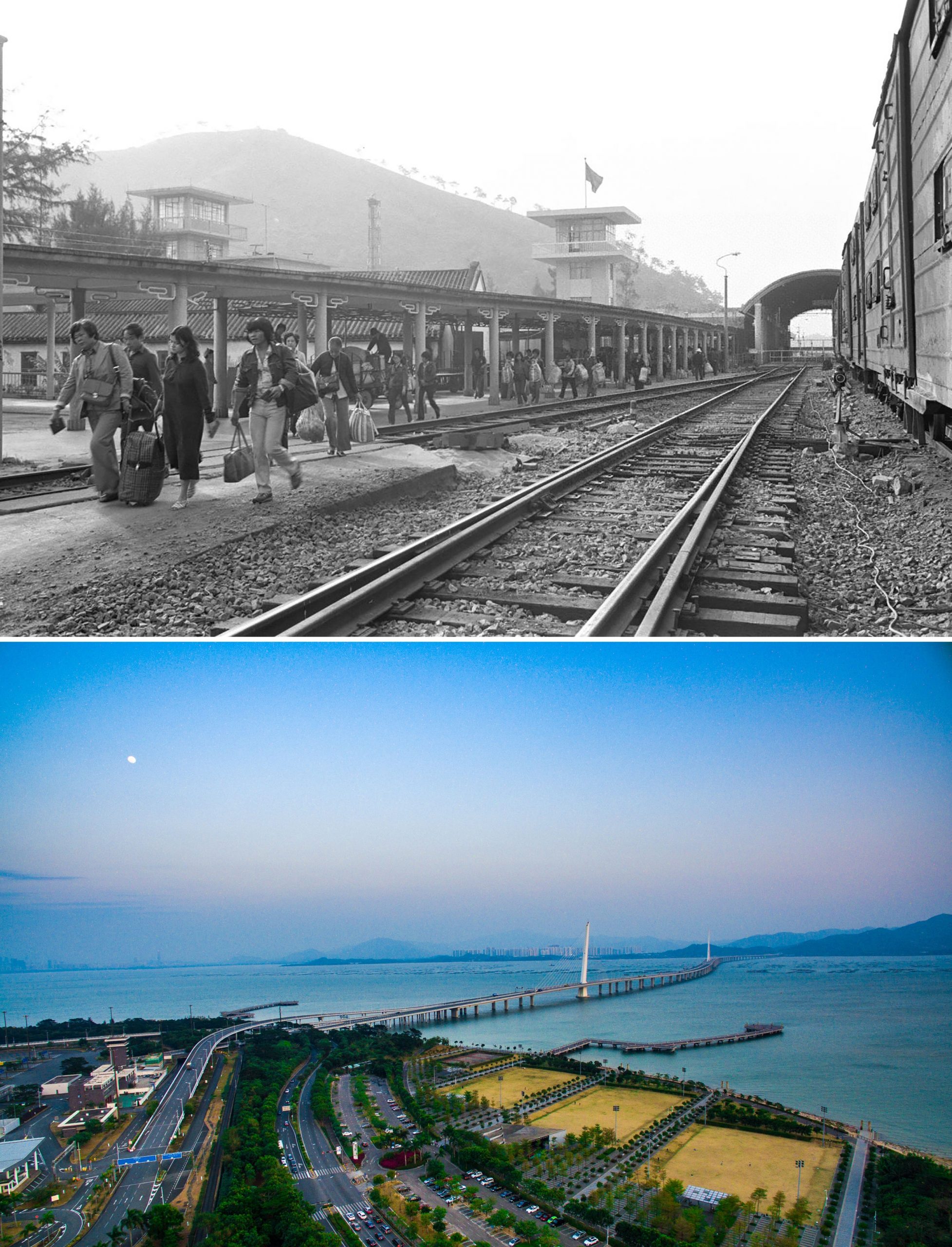

Bordering Hong Kong, Shenzhen began as a small farming and fishing village in the Pearl River Delta and more recently, a low‑cost, labour‑intensive manufacturing centre. Thanks to China’s reform and opening‑up policy in the late 1970s, Shenzhen has become a modern and economically flourishing hub in the consumer electronics world. The city is now also known as ‘China’s Silicon Valley’ and ‘Silicon Delta.’

Around the globe, there have been numerous efforts to replicate the famed Silicon Valley. While some have been relatively successful, other efforts have proven mediocre or ineffectual. Within China, the Shenzhen special economic zone (SEZ) is by far the most successful one.

While the two clusters operate under two rather distinct political and economic systems – the Bay Area being a market economy whereas Shenzhen is a planned economy – both have been recognised as innovation and technology hubs with great economic success. Comparing these cases at the extremes of the institutional spectrum can provide different angles in understanding how the two clusters emerged, evolved, and proved sustainable.

Valley and Delta

The term ‘Silicon Valley’ in the US often refers specifically to the area around San Jose, California. Despite this, conceptually most people would also associate San Francisco with Silicon Valley, generally known as the San Francisco Bay Area, which encompasses both the San Francisco‑Oakland‑Hayward and San Jose‑Sunnyvale‑Santa Clara metropolitan areas. In 2015, the Bay Area had a population of 6.6 million across 13,357 sq km of land area meaning a population density of 495 people per sq km.

By contrast, the city of Shenzhen concentrates its much larger population into an area a fraction of the size of the California metropolitan areas. Shenzhen’s 10 districts cover just 1,997 sq km of land area, and in 2015, it had a population of approximately 11 million with 5,697 people per sq km. It has grown into a vibrant city dotted with stores, restaurants, hotels, and offices along its commercial boulevards. In 2016, there were 128 skyscrapers completed around the world. China accounted for 70 per cent of the pool; Shenzhen alone had 11 skyscrapers, more than the entire US.

From 2010 to 2015, Shenzhen’s GDP grew at a rate of 79 per cent, easily surpassing the 29 per cent and 44 per cent growth rates of San Francisco‑Oakland‑Hayward and San Jose‑Sunnyvale‑Santa Clara metropolitan areas respectively. This year, Shenzhen’s GDP is expected to reach US$350 billion, surpassing the projected US$345 billion GDP of neighbouring Hong Kong.

Behind these staggering rates of economic growth, Shenzhen’s real transformation comes from the alteration of its industrial composition. In the past two decades, the city has evolved from being a base for hardware manufacturing to become a centre of higher‑end manufacturing production and an innovation hub. It has had great economic success in recent years, coming in fourth in the Milken Institute’s “Best‑Performing Cities China” rankings for 2016 and 2017.

Early success and evolution

The origin of Silicon Valley can be traced back to the leadership of Stanford University. Frederick Terman, then a professor at Stanford’s School of Engineering, is widely credited as being one of the key facilitators in spawning this tech cluster. His leadership and efforts led to the emergence of many technology firms in the electronics industry including the Hewlett‑Packard Company (HP).

In the early years, many firms in the region received defence‑related funding. Terman’s vision, by founding the Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International), brought industrial workers to Stanford’s classroom to facilitate collaboration. By the late 1960s, the area had become known as an aerospace and electronics industry cluster.

Around the early 1970s, the area around San Francisco and San Jose developed expertise in the semiconductor sector. In 1971, journalist Don Hoefler coined the term ‘Silicon Valley’ in Electronic News. Some well‑known tech companies such as Apple and Oracle were founded there in the 1970s. By the 1980s, Silicon Valley had become the widely accepted centre of the computer industry and in the 1990s, renowned internet‑related companies such as eBay, Google, and Yahoo were established there.

Silicon Valley took advantage of the 1990s internet revolution and commanded its leadership in information technology.

Unlike Silicon Valley, there were no prestigious academic institutions at the onset of Shenzhen’s establishment. Its humble beginning as a small village changed radically as it first gained municipal status in 1979, then became one of the nation’s first of four special economic zones (SEZs) in 1980. Shenzhen’s location in between the mainland Chinese and Hong Kong made it an important intermediary in commodity circulation and factory imports.

At the outset of the SEZ’s establishment, the zone was set to focus on the electronics industry. Many electronics manufacturing and processing facilities relocated from Hong Kong to Shenzhen. Founded in 1986, the Shenzhen Electronics Group Company initiated China’s first electronic parts supply market, nurturing entrepreneurship in the city.

From the 1980s to 1990s, Shenzhen’s manufacturing base successfully evolved from being an assembly centre of household electronics such as telephones and calculators to focusing on PCs and software, telecommunication, microelectronics, and new materials. In the 2000s, Shenzhen established its information and communication technology (ICT) industry. Subsequently, it has become an indispensable part of the global consumer electronic production networks.

In the last two decades, Silicon Valley has emerged as the world leader in high‑tech industries. Several innovative companies – Airbnb, Facebook, Tesla, Twitter and Uber, to name a few – have strategically situated themselves in the region. This clustering demonstrates Silicon Valley’s ability to foster an ecosystem ripe for entrepreneurial and innovative activities.

Since 2000, Shenzhen has become a global manufacturing hub for a variety of electronic products such as laptops and mobile phones. The municipal government established the Shenzhen Overseas Chinese High‑Tech Venture Park within the Shenzhen High‑Tech Industrial Park (SHIP) to attract overseas Chinese scholars and students to start their businesses (particularly in the high‑tech industries) in the city. Since around the mid‑2010s, Shenzhen has been more actively transforming itself from an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) centre to a technology and innovation hub by cultivating its indigenous innovation capacity.

Drivers for economic success

Many scholars have used various theoretical frameworks, including international and comparative development theory, regional science and urban economics (RSUE), new economic geography (NEG), and the study of institutions for cities and regions development. Despite their different angles, these theoretical approaches cover some common ground including the roles of capital, labour, innovation, entrepreneurship, universities, research institutes and cultures, along with institutions in determining the economic outcomes of cities and regions.

Through these lenses, we can compare the similarities and differences between the Bay Area and Shenzhen and identify the key factors contributing to their rise as innovation hubs and their economic prosperity.

Capital investment

The main funding source at the early stage of Silicon Valley’s establishment came from military contracts. By the early 1970s, venture capital (VC) replaced military funding as the major source for financing startup activities. A key factor in Silicon Valley’s early success is that many members of VC firms had their roots in the electronics industry and thus, could make sound investment decisions.

Venture capital has been an essential part of Silicon Valley’s innovation and entrepreneurial activities. As Professors Michel Ferrary and Mark Granovetter put it, “understanding Silicon Valley’s complexity and the hidden functions of VC firms can help policy‑‑ makers who try to create innovative clusters.”

Unlike the case of Silicon Valley, foreign direct investment (FDI) was the main source driving Shenzhen’s early economic development. In particular, the FDIs from Hong Kong and Taiwan spawned the early formation of Shenzhen’s electronic industry. Shenzhen offered preferential policies such as tax benefits and management oversight by investors to lure foreign investors.

In 1987, China’s first bonded area, the Shatoujiao Bonded Zone, was established to attract FDI. All these efforts have led Shenzhen to become one of the leading recipients of private foreign funding in China. From 1980 to 2015, the amount of foreign capital actually utilised by the city increased dramatically, from US$28 million to US$6.5 billion per year.

In 2000, the city set up an International High‑Tech Equity Transaction Center that specifically intended to facilitate high‑tech equity transactions and promote venture activities in China. In 2007, the Shenzhen Venture Capital Services Platform (SZ VCP) of SHIP was established. More recently, the Chinese central government set a policy mandate to promote entrepreneurial and innovation activities and launched a US$1.5 billion startup VC fund to cultivate innovation‑driven sectors.

More recently, the Chinese central government set a policy mandate to promote entrepreneurial and innovation activities and launched a US$1.5 billion startup VC fund to cultivate innovation‑driven sectors.

Sourcing human capital

For more than a century, the US has been a nation where people are free to migrate of their own will. On top of a high rate of domestic migration among states, California in particular has been a melting pot consisting of a variety of ethnic and racial groups with varied backgrounds and talent.

Historically, migration for most people in China was discouraged, due to the country’s hukou (household registration system). Despite the difficulty in getting a permit, many found loopholes to sneak into the SEZ. Gradually, as Shenzhen relaxed its limit on permits, more young Chinese graduates with ambition and vision have flocked to the city since the 1980s.

Human capital flowing into Shenzhen through both formal and informal conduits is recognised as the key for Shenzhen’s economic success. A report released by Ant Financial (affiliate company of Alibaba), a Chinese fintech company, regarding the destination of recent university graduates in 2015 showed that the outflow of college graduates from to Shenzhen was number one in the nation.

Where the Bay Area has long been open to migration and immigration, Shenzhen initially had a tight control on labour and residential mobility but later relented. Ironically, the central government’s early tolerance of informal and illicit practices helped the accumulation of capital and knowledge. If there is a shared value between the two cities that helped foster growth, it would be the openness of the society and the ability to attract talent. The two city‑regions are more like ‘sister’ cities in that regard.

Universities and research institutes

The presence of strong research universities and institutes is associated with the formation and development of high‑tech clusters. Stanford University played a key role in the formation of Silicon Valley. The Bay Area is also home to many universities anchored by the University of California, Berkeley. These academic institutions are essential sources to the local talent supply and are critical to the cultivation of innovation capacity and the growth of the Bay Area.

By contrast, Shenzhen had no strong research universities or institutes. Shenzhen University was founded in 1983 as one of the earliest academic institutions in Shenzhen. A decade later, Shenzhen Polytechnic was founded, and a number of Chinese renowned academic institutions such as Peking University and Tsinghua University have established satellite campuses in the city. Despite these efforts, some argue that such institutions did not contribute to the formation of Shenzhen’s IT cluster.

Innovation and entrepreneurship

As Shenzhen became a global processing and assembly centre for telecom and mobile phone production, competition from other low‑cost cities in China has also gradually eroded Shenzhen’s cost advantage. To cope with these challenges, the city has been trying to upgrade its industries through bolstering its innovation capacity. By the second half of the 1980s, Shenzhen had attempted to nurture innovation and entrepreneurial activities by encouraging high‑tech professionals to become shareholders of private enterprises.

One of the key strategies in fostering high‑tech industries was to establish industrial areas such as the SHIP (founded in 1996). These industrial parks typically provide their customers with low‑cost spaces and readily available equipment as well as streamlined administrative services to help jumpstart small tech‑oriented businesses. In 2000, the Shenzhen Overseas Chinese High‑Tech Venture Park in SHIP was established to attract overseas Chinese students to start their businesses in Shenzhen. This park provides entrepreneurs with physical infrastructure and services in financing, consulting, training, networking, and marketing.

In addition to cultivating high value‑added industries such as IT and electric car production, Shenzhen has recently pushed for innovation and entrepreneurial activities. In particular, the city is trying to create more makerspaces where entrepreneurs can design, prototype, and create manufactured products.

The complete and low‑cost supply chain for electronic manufacturing provides Shenzhen with huge advantages in innovation and entrepreneurial processes. As a capital for hardware, it has a complete ecosystem that can offer easy and timely access to low‑cost equipment and parts for all stages of electronics production and has attracted about a thousand startup accelerators to the city.

Shenzhen’s persistent efforts in advancing its high‑tech industries are reflected in the statistics. In 2001, the value of exports of the high technology industry was US$11.4 billion. By 2015, this number jumped by more than 12‑fold to US$140.3 billion. From 2004 to 2015, the city’s number of Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) international patent applications increased by 40 times, from 331 to 13,308.

Professional culture and institutions

According to one expert, the openness, culture of collaboration, and informal interaction between firms and talented professionals play key roles in the success of Silicon Valley. These factors also helped the Bay Area cope with the challenges from the tech bubble burst in the early 2000s. The rebirth of the Bay Area technology cluster after the tech bubble burst made the region stronger as a leader in both the technology world and in broader regional economic development.

Unlike Silicon Valley, research has found that there is no significant relationship between the spatial agglomeration of firms in Shenzhen’s information and technology (ICT) industry and their innovative performance. This is due to a lack of interest in interaction among firms in the industrial clusters. As a result, the innovation of most firms mainly comes from their internal R&D activities rather than from technology transfer or knowledge spillover.

Although the designation of SEZ gave Shenzhen a relatively high level of autonomy compared with other Chinese cities, it was not quite an open economy. Nevertheless, the dramatic contrast in lifestyle and economic developmental status between Hong Kong and Shenzhen gave the city impetus to be more open and receptive to institutional changes. One of the key factors leading to Shenzhen’s current success is its ongoing restructuring and streamlining of administrative institutions. For instance, the city has been reforming its industrial and economic management systems since 1981.

Shenzhen night view, 2018 (bottom) | Photos by Xinhua News Agency

The ability of these regions to transform perhaps stems from the open culture and intense competition on the enterprise level or the ability of the government administrators to quickly retool policies to accommodate new economic and corporate needs – or some combination of the two.

Complexity of replicating success

The two city‑regions clearly followed different paths: prestigious higher education institutions such as Stanford University played a key role in spawning Silicon Valley whereas Shenzhen had no such endowment at its early developmental stage. Both city‑regions have been known for their electronics industries, yet where the Bay Area has been pushing the global innovation frontier, Shenzhen began with low‑cost manufacturing and currently strives to nurture indigenous innovation capacity. The Bay Area operates within a market economy, whereas Shenzhen situates in a socialist market economy; a hybrid of a planned and market economy.

The developmental pathways of the Bay Area clusters and the Shenzhen high‑tech economy cannot be more different in orientation, pace of development, utilisation of private funding, and most notably, the roles of government in the process of building these regional economies. As such, it is difficult to draw on the success of these two economies too broadly to define sets of policies or practices in ‘making’ a successful high‑‑ tech economy.

Assessment of contributing factors in both city‑regions shows that an open policy that allows free flow of capital and labour contributes to a fertile environment for innovation and entrepreneurship. It also finds that while the role played by universities and research institutes may not be necessary for the formation of a tech cluster at its early stage of establishment, these institutes are essential to long‑term economic development.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Michael C. Y. Lin is a Senior Associate in regional economics at the Milken Institute. His current research focuses on urban and regional economic development in Asia and the United States.

Perry Wong is Managing Director of research at the Milken Institute. He is an expert in regional economics, development and econometric forecasting, and specialises in analysing the structure, industry mix, development, and public policies of a regional economy.