TEXT Richard Lee

Many people know about the incredible work Jesuit priest, traveller, trader, linguist and diplomat João Rodrigues ‘Tçuzu’ did in Japan in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. But there was much more to this incredible interpreter – including his influential missions into China and his absolute dedication to his late-life home of Macao.

Millions of tourists stand and marvel at the Ruins of St Paul’s in Macao every year. They learn about the history of the great building that was destroyed by fire during a typhoon in 1835. They take selfies with the remaining façade in the background. What they probably don’t do is research who was buried just behind those iconic ruins. If they did, they’d find out that the body of one of the most talented, important and influential Jesuits in history once lay in St Paul’s Church before that great fire: the body of João Rodrigues ‘Tçuzu’.

More than 200 Jesuits were once buried at the Ruins of St Paul’s – their graves sadly disappearing after the savage fire – but João Rodrigues ‘Tçuzu’ has to be one of the most significant. This Portuguese traveller, scholar, priest, missionary, trader, sailor, warrior, linguist and diplomat helped transform China and Japan in the way these nations worked with the European Jesuits in the 16th and 17th centuries. His profound knowledge of the people, culture and language of Japan, where he spent 33 years of his life, earned him the moniker of ‘Tçuzu’, a Portuguese transcription of the Japanese word for ‘interpreter’. But he achieved so much more than just his work in Japan, bringing his knowledge and experience to Macao, the city he eventually called home and the city he eventually died in.

Rodrigues was born in 1561 or 1562 in the municipality of Sernancelhe, which is about 100km east of Porto in the north of Portugal. He took his first breaths in the picturesque diocese of Lamego at a time when the European country had been at the forefront of global overseas explorations for at least a century – and had many years ahead of it as a world exploration leader, not least in Asia. Little is known about his early years but we do know that by the age of 14 years old, he had left Portugal on a two-year voyage to the East that was both arduous and dangerous. He was about to become an important figure in Portugal’s global exploration mission. And during this voyage, Rodrigues first set eyes on Macao.

The first glimpse

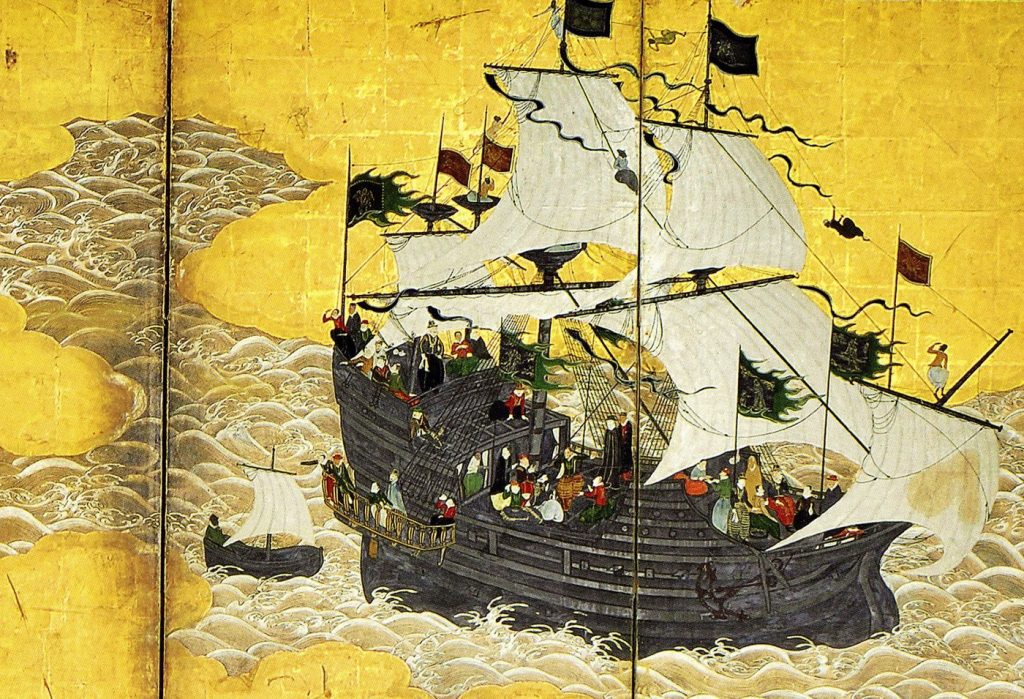

Macao was a long way from home for a teenage Rodrigues. For many Portuguese sailors, this city, which was established in 1557, would have seemed like the far end of the world. Rodrigues’ first glimpses of Macao must have filled him with awe and wonder but, sadly, little is known about these first impressions of the city and, indeed, how long he stayed there as he waited for passage on a ship to Japan – his ultimate destination. He probably didn’t have to wait for long as he arrived in Nagasaki in 1577, which was towards the end of Japan’s Sengoku period of near-constant civil war and social upheaval over almost 150 years.

The following years in Japan were tough for young Rodrigues. He’d bravely flee for his life from battles, he’d starve almost to death and he’d freeze in the icy lands of the Asian country during winter. But one important thing happened to the young man in Japan that was likely influenced in part by his short time in Macao: he became a Jesuit, a member of the Catholic Society of Jesus which had been founded in 1540 and had been sending missionaries out from Europe across Asia ever since.

Macao had become the Jesuits’ base in Asia but Rodrigues is believed to have officially joined the order on 24 December 1580, in Usuki, Japan. Meeting Jesuit missionaries in Macao may have influenced this decision but it’s most likely that he was heavily influenced to join in Japan. Tereza Sena, a researcher at the Macao Polytechnic Institute’s Centre of Sino-Western Cultural Studies who has published more than 60 works on the history of Macao, including pieces on Rodrigues, says: “The fact is that we don’t know how long Rodrigues was in Macao that first time he visited. The Jesuits were becoming influential at that time in Macao but it is likely that he became acquainted with more Jesuits in Japan and became naturally impressed with their blossoming mission there. Either way, he became a Jesuit and that was the real beginning of Father Rodrigues’ story.”

Paulo Pinto, communication technician for the Social and Cultural Service Department at the District Council of Sernancelhe, says: “Father João Rodrigues is probably the most well-known person from Sernancelhe, especially one so well regarded beyond national borders. It is a shame we don’t know more about him or what made him decide to embark [from Portugal] but there are two possibilities. One is that, like most young men, he moved to Lisbon in order to work on the ships and eventually decided to join one of the crews. The other is that Sernancelhe is home to one of the oldest Jesuit sanctuaries in the country: The Lapa Sanctuary. There are some historians who believe that, despite the fact Rodrigues only took vows in Macao, he first came across the Jesuits right here at home. While I personally favour the first, I have to admit the second explains his scholarly success. Most young men who were not wealthy or connected somehow to the church would not have known how to read, let alone speak any languages.”

The first permanent Jesuit residence in Macao was built in 1565. By 1594, St Paul’s College was founded by Jesuits, earning it the title of the first Western university in East Asia. Macao journalist and historian, João Guedes, says this was ‘the first Western university in the Far East’ and he notes that Macao had been chosen as a ‘stronghold’ by the Jesuits during their ‘evangelisation of Japan’. American historian and author Michael Cooper, in his acclaimed 1974 book ‘Rodrigues the Interpreter: An Early Jesuit in Japan and China’, observes that St Paul’s College was built ‘with the needs of the Japanese mission especially in mind’ as the facility could – and, in fact, did – ‘provide training facilities for the Japanese clergy’. Cooper notes that ‘Rodrigues was about 19 years old when he entered the novitiate’ – the period of being a ‘novice’ in a religious order – in Japan. In 1581, he was ‘one of five Portuguese scholastics or students for the priesthood at the college of St Paul in Funai’, notes Cooper. He stayed and trained for five years before returning to Macao.

In Macao, Rodrigues became an ordained priest in 1596. It had taken around 14 years for the scholar to complete his studies due to turbulent times between the ruling powers and the Jesuits in Japan and because he’d found his vocation as an interpreter. Rodrigues had shown a great talent for the Japanese language and would have done, as Cooper puts it, ‘interpreting work at some time in the 1580s’ which would have interrupted his theology studies. His studies were also interrupted in 1591 when he was a key figure as the Jesuits met with Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who was, at that time, effectively the leader and ‘second great unifier’ of Japan.

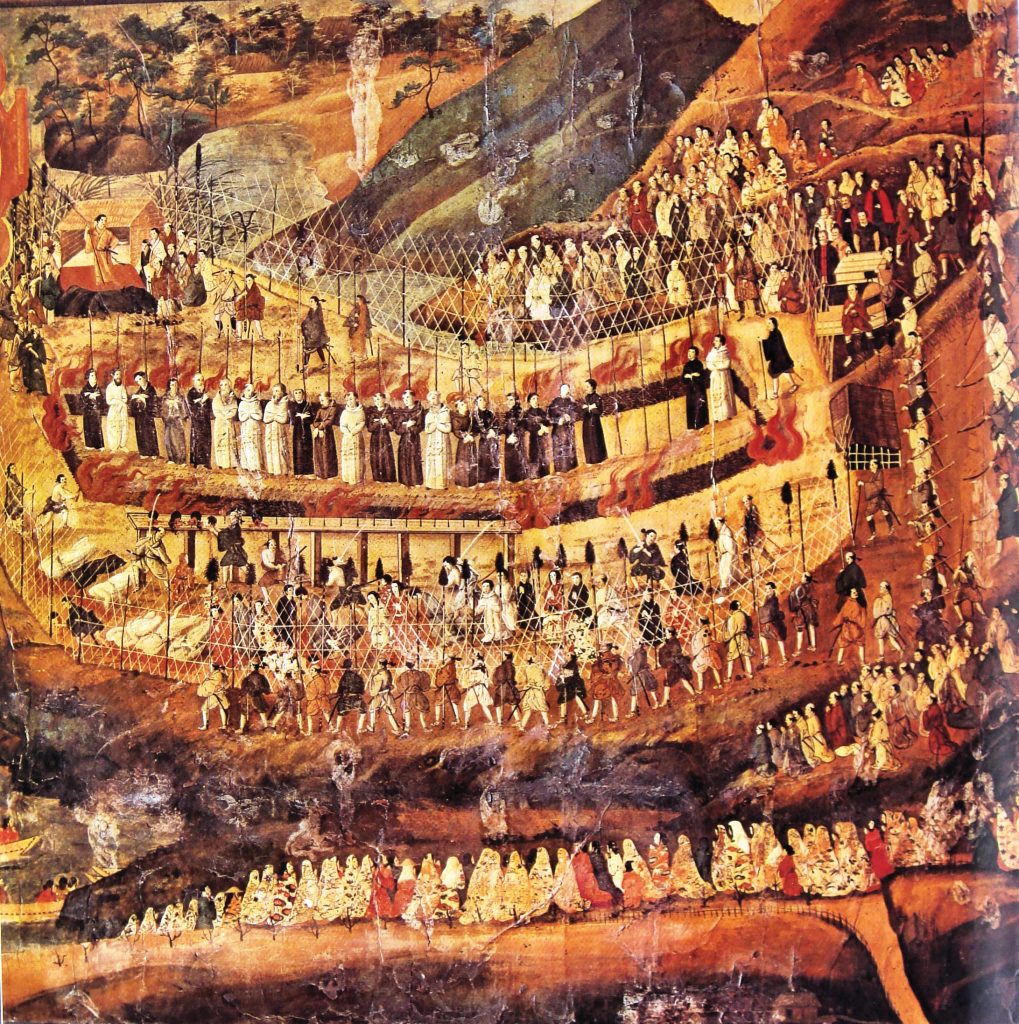

A Jesuit embassy met Hideyoshi in the city of Miyako with Rodrigues – who Cooper notes as having become ‘something of a celebrity in Miyako’ due to his ties with the rulers and his interpretation work – in tow. The meeting started a tumultuous relationship between the Jesuits and Hideyoshi, with the Jesuit missionaries eventually being effectively expelled and sent back to Macao, mainly because of their different beliefs and growing power. As Cooper notes, however, by October 1592, ‘Rodrigues was the only Jesuit who had official permission to remain anywhere in [Japan]’. Before that, there had been executions of Catholic missionaries but Rodrigues remained in favour with Hideyoshi and they remained friends right up until the Japanese ‘unifier’ died in 1598.

João Botas, journalist, historian, author and former Macao resident who runs the Macau Antigo blog about the city’s storied past, says: “Rodrigues wasn’t just a simple translator. He was much more than that. He would have arrived in Japan as a 16-year-old boy and very quickly became an expert on the Japanese language, culture and religion. He became an interpreter – a ‘tçuzu’ – who was greatly respected by the Japanese and Chinese authorities. He wrote the first Portuguese-Japanese dictionary and, in Macao – a city where he became the Japan procurator for the Society of Jesus – he also wrote about the art of Japanese tea. He was open-minded and a true diplomat.”

Macao and the trade battle

When Rodrigues was ordained as a priest in Macao in 1596, he had become well-known and respected in the city, not least because of his work with the Japanese. But his relationship with many fellow Jesuits was about to be tested because of a trade war that involved Macao. In the minds of the Japanese, the Jesuits and the Portuguese traders had become inextricably linked because, as Cooper explains in his book, ‘the Portuguese were not selling their own European products to the Japanese but were merely acting as middlemen in an essentially Asian trade. The Japanese wanted Chinese silk and the Chinese wanted the silver being mined in increasing quantity in Japan’. Enmity between Japan and China barred direct trade so, as Cooper puts it, the missionaries could ‘see considerable profits to be won by investing in the silk trade between Macao and Nagasaki’. So the Jesuits began profiting from the silk trade.

The trade war raged in the 1590s, with Jesuit buildings in Japan being dismantled in retaliation to the profiting missionaries and Portuguese merchants ceasing all trade at one point in retaliation but by Hideyoshi’s death, the Macao-to-Japan trade route had been restored. Rodrigues had been involved at times in the 1590s but it was in 1601 that he became a central figure because it was in that year that he was appointed as Tokugawa Ieyasu’s ’personal commercial agent’ in Nagasaki. Ieyasu, the ‘third great unifier’ of Japan, was the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate, which ruled Japan from 1600 to 1868. In 1601, he announced, as Cooper says, ‘that thenceforth the Portuguese merchants should make their transactions’ through Rodrigues, due to the Jesuit’s influence and the trust the Japanese had in him. It made him both beneficial and dangerous to the Jesuits as he had such a strong say in the annual prices of the silk coming from Macao and could favour either party.

In 1609, a trade ship carrying silk from Macao arrived at Nagasaki. It was commanded by Captain-major André Pessoa, Macao’s acting governor, who had just resolved a riot in the city by having 40 Japanese people who had ‘barricaded themselves in a house’ killed. News of that incident, plus the impact of new Japanese links with Dutch traders, led to an arrest warrant being issued for Pessoa but he got wind of it, withdrew his ship and then defended it from the Japanese out at sea for three cold days in January. In a final act of defiance outside Nagasaki, he blew it up, killing himself and his crew. Ieyasu’s patience with the Portuguese and the Jesuits had expired. And that meant all of them. According to Guedes, as ‘Rodrigues was the most exposed Western political figure in Japan’, he was among the first Jesuits to be expelled. In Cooper’s words, in March 1609 ‘a junk left Nagasaki taking João Rodrigues to Macao. He was sent into exile after 33 years in Japan’.

The China chapters

The success of the Portuguese silk merchants had made Macao an important place in the eyes of the Japanese in the early 1600s. But it was not yet seen as so important by the Chinese. In 1610, a 49-year-old Rodrigues arrived in a city that wanted to elevate itself in the eyes of the Chinese leaders. He understood this ambition and for the next five years he forgot all about his adventures in Japan and turned his hand at learning all he could about China so he could help his fellow Jesuits make inroads into the Middle Kingdom. He was also put in charge of drawing up an annual report on the city for Rome and he regularly taught classes at St Paul’s College, instructed sermons, performed parish functions and worked as an attorney.

At the same time, Rodrigues also worked hard on his writing. His ‘The Art of the Japanese Language’ book – which is now credited as being the oldest fully extant Japanese grammar work in history – had already been published in Nagasaki between 1604 and 1608. In Macao, he went on to write ‘The Short Art of the Japanese Language’, which established clear and concise rules in the language and was published in 1620. He also began ‘The History of the Japanese Church’ in Macao, which is less about the Jesuits and more of a complete overview of Japanese language, history and culture, including much praise for the holiness of Buddhist monks. It was finally translated into English by Michael Cooper in 2001. Other works by Rodrigues included pieces on history, geography, customs, astronomy and even tea.

By 1615, Rodrigues had travelled across China many times, often visiting Christian communities in cities like Beijing, Nanjing and Hangzhou – then known in English as Peking, Nanking and Hangchow. According to Cooper in his book, Rodrigues ‘had plenty of opportunity to observe the work of his fellow Jesuits and it is evident that he was not happy with everything he saw’, expressing strong opinions on how Christianity should be taught in China. Back in Macao in 1615, he became a key diplomatic figure between the Jesuits and the Chinese. Since 1603, the Jesuits had been building a recreation area at Ilha Verde – where Rodrigues incidentally lived – in the northwestern part of

the peninsula. The Chinese authorities, however, worried that a fort was being constructed – but Rodrigues persuaded them that this was not the case. In June 1622, the lack of fortifications meant the Dutch, who wanted Macao and its silk trade for themselves, invaded but they were thwarted, not least by the Jesuits who had hurriedly bought eight cannons for the city.

Following the attempted Dutch invasion, the Jesuits wanted a fort but the Chinese authorities – for obvious reasons – were still against it. The fact is that the famous Monte Fort, which still sits just above the Ruins of St Paul’s, was already under construction and had been used during the invasion but the Chinese did not want this to stay. Rodrigues again became a key diplomatic figure as he travelled into the Mainland and spoke with an important chief justice. Cooper, in his book, notes that Rodrigues spoke ‘with such determination against pulling down the walls that the official became annoyed and regarded him as responsible for the non-fulfilment of the order to dismantle the defences’. The fort’s walls were eventually saved, with Cooper noting that ‘a certain amount of money’ changed hands before ‘the order for their destruction was rescinded’. That was good news for the Jesuits but for Rodrigues, it was not so good. For the rest of life, his actions would be criticised by some members of the Chinese authorities.

The final years

Despite the criticism, 1622 was not the last year that Rodrigues ventured into the Mainland. In 1630, he accompanied a Portuguese military party and its cannons from Macao to Beijing. As Guedes tells us, at that time the Portuguese art of artillery making was ‘way ahead of its time’ and he notes that Manuel Tavares Bocarro, a famous cannon-maker, had his main factory in Macao and ‘sold his guns across Asia’.

The party wanted to help the Ming Dynasty leaders defend China from the invading Manchu forces – who eventually succeeded and formed the Qing Dynasty and did so well they were invited back later in the year. Rodrigues again went along and peeled off with a handful of friends from the group to visit Dengzhou then known in English as Tengchow. This proved to be a costly decision as he got caught up in a revolt by a part of the Ming Dynasty army. Besieged for a month in the town’s fortress, he watched as his Portuguese friends died around him.

Father Rodrigues deserved the Chinese emperor’s recognition in his day and he desrvers our recognition today.

– Tereza Sena

Rodrigues was 71 years old at that time. As the fortress was being taken, he was forced into doing something no septuagenarian should try. He jumped from the high fortress walls and into the February snow that lay below. He survived, retreated to Beijing and managed to make his way back to Macao by 1633, where he returned to writing ‘The History of the Japanese Church’. He never completed the book. He died on 1 August 1633. In a letter dated 4 January 1634, Jesuit priest André Palmeiro wrote that Rodrigues had died because he ‘neglected to attend to a hernia in time’. As Cooper – who once lamented that a ‘one-volume biography’ could not do Rodrigues’ life justice – puts it, ‘very possibly the injury had been caused by jumping off the battlements and undergoing other physical hardships during the trek’ from Tengchow to Beijing and back to Macao.

Ana Cristina Dias, a University of Macau lecturer who has a PhD in the history of the modern world, quotes other historians in saying that throughout his life, Rodrigues ‘played the part of a historian, archeologist and anthropologist’ as his written works often focused on ‘all aspects of life and man’. She adds that ‘above all, he was a brilliant linguist’, labelling his book ‘The Art of the Japanese Language’ as a masterpiece. She says that in Beijing in 1632, he was ‘officially honoured by the Chinese Emperor, who granted him a plaque’. “This is of special significance,” she says, “because, as far as we know, this was the first time the Chinese referred to a priest as a ‘Jesuit’ instead of the common ‘scholar of the great West’. It goes to show that he was someone well-versed in the language who was respected in the Chinese court and who represented his religious order with great honour.”

Botas recounts an interesting story he learned about Rodrigues after his death in Macao: “In October 1644, the Chinese authorities, in order to honour Rodrigues after his death, gave the Jesuits a piece of land in Ilha Verde, which was an actual island at the time, for him to be buried in. A year later, they gave another piece of land on Patera Island to the Jesuits for his burial. As far as I know, there are no records saying that his body was transferred to either of these places so it’s most likely that he remained buried at St Paul’s. Although he had a more important role in Japan, he is for sure among Macao’s 10 most important historical figures. But I think the large majority of locals in Macao now just don’t know anything about him. But James Clavell did when he wrote his famously televised 1975 novel ‘Shōgun’ and based the character of Martin Alvito on Rodrigues.”

Tereza Sena says that Rodrigues’ ‘adventurous escape by jumping from the fortress at such an advanced age’ was both incredible and added yet more weight to the man’s legend – a legend that survives today. Sena believes this legend should be safeguarded for future generations in Macao and beyond. “His diplomatic, linguistic and sinological contributions should be taught at schools and at public talks,” she says. “His works, including his eulogies, memorials and letters describing Macao’s military expeditions in support of the Ming Dynasty, should be on display at exhibitions. He deserved the emperor’s recognition in his day and he deserves our recognition today.”

Sena continues: “Father Rodrigues’ contributions to China were accounted in Chinese annals and he was certainly a special figure in the history of Macao. Of course, he did not act alone but he had the skills to successfully accomplish missions from Macao into China. Due to his experience as an interpreter in Japan, he was also presumably an influential figure when a team of official translators settled in Macao, probably in 1627. This office, which has naturally undergone adaptations over time, remained until the late 20th century as an important pillar for Macao’s Sino-Portuguese relations and aided the city’s survival for centuries.”

The body of João Rodrigues ‘Tçuzu’ once lay in front of the St Michael altar inside St Paul’s Church before the building became the ruins that are included on the UNESCO World Heritage List today. Guedes says that this inclusion on the list is the ‘best legacy of the universalism of João Rodrigues’ after he was ‘forever laid to rest inside the church’. ‘Tçuzu’ was indeed one in a million. It’s as if the man – who was believed by some Portuguese people in his day to be up to 250 years old – was capable of anything, from interpretation and diplomacy to scholarly pursuits and extreme physical endurance. Many other stories are attached to him – such as his role in helping to revise the Chinese calendar and his arguments with fellow Jesuits over what religious terminology should be used in mission work in China. In his day, Rodrigues became a key figure in Japan and China, as well as in both Jesuit and Portuguese history. And his name still echoes around Macao, the city he wrote his masterpieces in, the city he helped to defend and the city he eventually called home.