Local artist prepares for the biggest debut of his career: the Venice Art Biennale

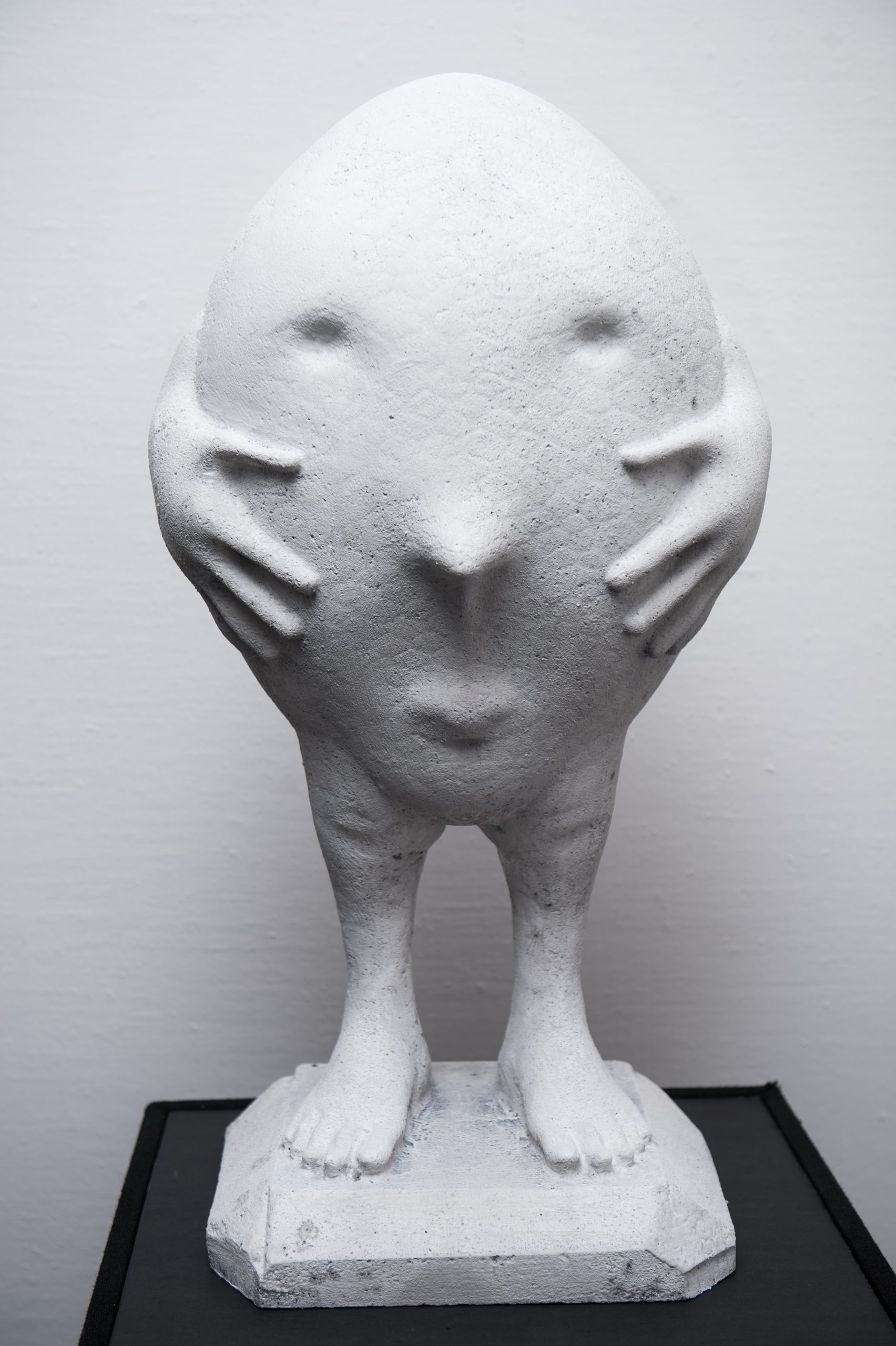

Macao artist James Wong Cheng Pou is preparing for the greatest exhibition of his career: 57th La Biennale di Venezia, or the Venice Art Biennale, to be held from the 13th May to 26th November. Hundreds of thousands of contemporary art aficionados will view his work, which includes paintings as well as 3D pieces.

According to Wong, “This is the most important exhibition for any artist. It is an international platform that attracts people from around the world.” Inclusion was not via application; rather, Wong was chosen out of a group of nearly 40 Macao-based artists by a panel of five judges from the Macao Museum of Art.

Representing Macao at this prestigious international event will be the high point thus far of a rich and varied professional journey that has taken Wong from Macao to Hong Kong, Japan, Taiwan and the Slade School of Fine Art in London. His curriculum vitae includes arts education and museum planning as well as a wide repertoire of paintings, prints, sculptures and art installations. He has also headed the Division of Arts Research and Museology at Leal Senado and was co-ordinator of the Ethnography Exhibition at the Luis de Camoes Museum.

This is the most important exhibition for any artist. It is an international platform that attracts people from around the world

James Wong

Early inspirations: cinema and manga

Born in Macao, Wong was the fourth of eight children. His father worked in the family business distributing fruit before gaining employment with the Macau Ferry Company where he remained until his retirement. His mother was a full-time housewife. “Life was simpler in those days. There were not so many material things. I used to play with my friends on the streets. Neighbours knew each other. Our friends included children from richer families who gave us food and toys. There was no societal pressure of any kind.”

He attended Jesuit primary and secondary schools, receiving his education from priests and nuns from Britain, Ireland and Italy as well as Macao. “I was impressed by their willingness to make sacrifices and serve society. They helped students with their homework but also with more personal problems. From them, I absorbed the concepts of generosity, good behaviour and self-discipline.”

Wong had his first introduction to the world of art via two weekly courses in the primary school curriculum. He began to paint at home and was further encouraged by his father. “Television had just become popular, and I liked to watch Japanese manga and cartoons, things that I could not see in Macao.” He purchased foreign magazines and cartoon books for inspiration.

His artistic interests were also cultivated by cinema. “There were many cinemas in Macao then, including one opposite our apartment. I often went because they let me in for free. My father liked films too. Films had a very big influence on me,” he recalls.

At the time, Macao had no universities or art schools, so upon graduating secondary school, Wong went to Hong Kong to continue his studies. He lived in Tai Wo Hao with his grandmother and uncles, “which was so lively and colourful – very different from Macao.”

Setting off to see the world

Initially, Wong wanted to be an architect, but his family did not have the money to put him through school, so he paid his way through art school by working odd jobs. “A friend found me a job at the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club (RHKYC), which included meals and accommodation at its facility on the water… I saw a new world, in that boat on the sea, and it was a great opportunity to practice my English.”

He attended art classes at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, a school in downtown Wan Chai that had a great reputation whose teaching staff often went on to become top designers in Hong Kong. To gain more experience and inspire their nascent artistic expression, Wong and his classmates went to study abroad. “Fees in the United States were very expensive. Programs in Paris were free, but you had to speak French. Four of us from the RHKYC decided to go instead to Japan, where we could study and find jobs to pay our way. Except for the language, I felt familiar with Japan because I knew a lot of its culture from films, magazines and manga. It was an easy place to live, very clean and recognisable.”

In the four years Wong spent in Tokyo, he lived in various areas of the city to be close to his place of work. “I stayed with friends to save money. I studied what I wanted to study, especially design. It was not so commercial back then.”

As much as he enjoyed Japan, Wong never considered staying long term. “It is very hard to get good jobs which are reserved for the Japanese. Only if a foreigner becomes famous abroad will he be hired for a prime position.”

After Tokyo, Wong stopped over in Taiwan for six months where he produced designs for a classmate.

Influenced by the slade

In 1986, Wong returned to Macao, where, again, he helped a friend who had started a company. During the same time, he spent his evenings helping with translations of Japanese and English at the newly opened television station TDM.

In 1989, he proposed establishing an Academy of Visual Arts in Macao, fashioned after the prestigious School of Visual Arts in New York City. In the interim, the city prevailed upon him to teach printmaking at the Sir Robert Ho Tung Library. When the academy opened its doors in 1990, Wong became head of its Printmaking Department, a post he held until 1994.

To get the department up and running, the academy invited the input and aid of Portuguese print master Bartolomeu Cid dos Santos who had headed a similar department at University College London’s Slade School of Fine Art. Founded in 1871, The Slade is considered the United Kingdom’s top educational institution for art and design, recruiting a mere 40 students a year from around the world,

Upon returning to London, Cid dos Santos invited Wong to join him, an invitation he gladly accepted. From 1993 to 1996, Wong was an honorary research assistant at The Slade. “I learned so many things there. I taught students who were the cream of the crop from all over the world. We had hopes that the Macao academy could become a sister school.”

When he returned to Macao, Wong continued his work at the academy, focusing on planning a new cultural project. Scheduled to open in 1999 to a cost of US$100 million (MOP800 million), the culture centre was to include the Macao Museum of Art, two auditoriums for performances as well as the Handover Gifts Museum. However, after six months, Wong found himself disinterested in the logistics of the project. He returned to The Slade for two more years and took courses and volunteered at the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Life after the cultural centre

1997 was a turning point for Wong: the Macao government and his friends both beseeched him to return and finish building the cultural centre. Faced with the decision of remaining in the UK, Wong ultimately made the choice to return to his hometown.

Wong has since devoted himself to teaching and focusing on his own compositions. He has also published two books and has penned a weekly column for Macao Daily since 1990

Back in Macao, Wong applied the knowledge and experience he had acquired in London to the centre. With his colleagues, he visited major regional museums for ideas and inspiration. “I urged the government to follow international standards and build facilities to last 50 years. I left the project in January 1999 and handed the work to my successor. When I see the Museum of Art and other facilities, I see them as my biggest contribution to society.”

Wong has since devoted himself to teaching and focusing on his own compositions. He has also published two books and has penned a weekly column for Macao Daily since 1990.

He has held numerous solo exhibitions, including his first in 1987 at Macao’s Museum Luis de Camoes. His work has also been on display at the Camara Gallery in Portugal, the National Gallery of Belgium, a gallery in Bunbudo, Japan, and The Slade School. Other clients include the Oriental Foundation in Lisbon, the Peninsula Hotel of Hong Kong, the Shangri-la Hotel in Beijing, the Macao Museum of Art and Macao’s MGM and Crown hotels. In 2010, Wong received the Sovereign Asian Art Prize. He is currently President of the Printmaking Research Centre of Macao and also Chief Curator of the Macau Printmaking Triennial.

Wong is creating all new pieces for the Venice Biennale due to on-site space restrictions. He plans on bringing three-dimensional models, installations, paintings and mobile images to this latest honour along his journey of art and adventure.