Macanese cuisine was the world’s first-ever example of fusion food. We look into the origins and evolution of this centuries-old tradition that must overcome modern challenges to stay alive. Find out who is fighting to ‘reclaim’ Macao’s iconic gastronomic heritage.

Few culinary traditions can boast they were a ‘global first’. But Macanese cuisine can claim it was the world’s first example of ‘fusion food’ as, over more than 400 years, it fused culinary influences and ingredients from a range of cuisines, primarily Portuguese and Chinese but also Malaysian, Indonesian, African and many, many others. It is a unique cuisine with a long history which has, over the years, become one of Macao’s most cherished cultural treasures, enjoyed by thousands of hungry diners every day.

Macanese cuisine has become so treasured that it became officially protected in 2017 when Macao was given UNESCO Creative City of Gastronomy status. The cuisine, which is also protected as an example of intangible heritage by the government, impressed the UNESCO judges who noted that the SAR ‘identifies gastronomy as a key lever for nurturing cultural diversity and supporting sustainable economic growth’. That statement referred to all gastronomy in the city, however Macanese cuisine has been a key traditional player in the city’s culinary success.

From the days when Macao was an important trading hub, inviting in cultural influences from across the globe, to today, with its status as an international tourism hub, Macanese cuisine has developed, improved and impressed. But since those early days, when some ingredients were hard to come by and others were far more prevalent, there’s a treasure trove of stories to explore before we can fully understand what the cuisine represents today.

Given the relatively small number of people who safeguard its unique traditions, Macanese cuisine has faced – and still faces – many challenges. It is a tradition largely passed down through generations of cooks who descended from the territory’s original Portuguese settlers and has been adapted and refined over the centuries to become what we know today. Globally speaking, it is a niche cuisine that will need the younger generations in Macao to keep it going and continue its evolution. With global culinary influences pouring into the city, this can be an enormous challenge, so there’s a need to ‘reclaim’ the cuisine and make it appealing to the younger generations of chefs and diners.

Tourists come to Macao and eat Portuguese food and think they’ve tried Macanese food but it’s not the same. We need to educate them on the real

But the challenges can be met, as they were in 1999, when the administration of Macao was transferred to China. Some people feared that Macanese cuisine could be on its way out as the territory’s culture changed. But this did not happen and, if anything, Macao has done more to preserve its unique cuisine over the past 20 years. This was highlighted on 21 January at a special lunch offered by representatives of the Macanese community. At the lunch, Chief Executive Ho Iat Seng expressed the government’s commitment to ‘Macao’s harmonious co-existence and multicultural society’. “Ethnic harmony and cultural harmony are an important part of social harmony and stability in Macao,” he said. “The SAR government has always respected the language and culture, life customs and religious beliefs of the Macanese community and will continue to support it.” With Macanese cuisine so central to the ‘life customs’ of the Macanese community, statements like this show the city’s dedication to preserving this gastronomic tradition for the future.

With the government behind the safeguarding of the traditions, we take a look at some of the players involved in preserving and taking Macanese cuisine forward into the 21st century, from the Macanese cultural groups to the next generation of local chefs. But first, we dive into the history of Macanese food to find out how such a unique blend of influences evolved into the cuisine we know and enjoy today.

A rich history

The Portuguese established settlements across the globe from as far back as the 15th century. These territories – none of which are now controlled by the European country – were usually along trading routes and once included communities like Mozambique in Africa, Goa in India, Brazil in South America and, of course, bordering China in the case of Macao. Each of these settlements across the world fostered unique cultures and traded influences and traditions as much as spices and precious metals. They were founded by merchants and adventurers who braved the high seas in search of new lands and trading opportunities. Many of these men married local women and set up home in these new communities, creating a melting pot of cultures in each port.

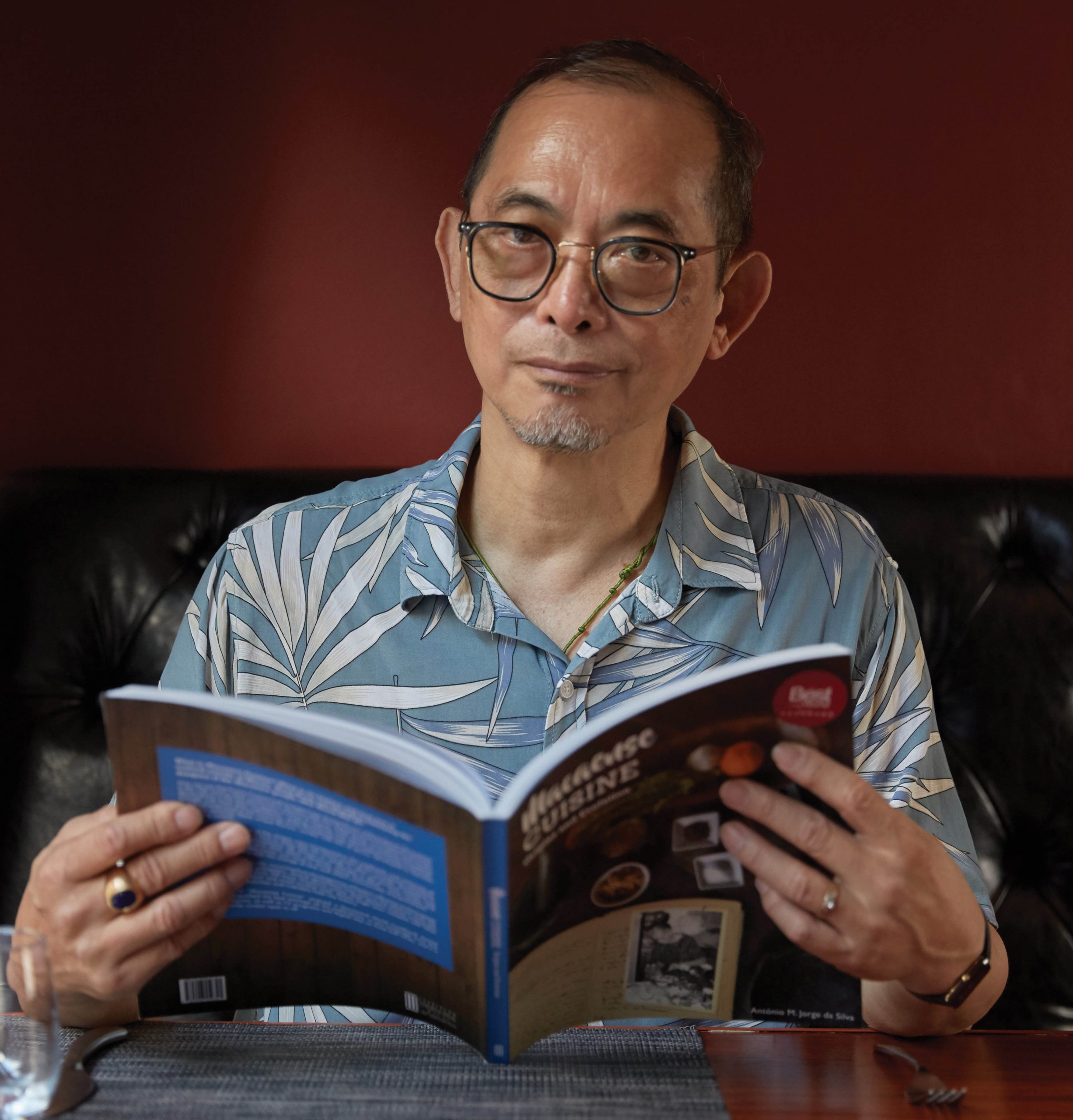

To understand the building blocks of Macanese food, we have to go all the way back to 1492 and the end of the 781-year occupation of the Iberian peninsula – modern-day Portugal and Spain – by Muslim forces from Africa, commonly known as the Moors. These Muslims, who revolutionised Europe with their progressive ways of thinking at the time but left the continent after their last leader surrendered to united Christian armies, left behind a cuisine that was rustic, regional and based on locally abundant ingredients. Seafood was an obvious centrepiece to Portugal’s cuisine at the time, as well as ‘a variety of vegetables, potatoes and meat products’, according to historian António M Jorge da Silva in his book ‘Macaense Cuisine – Origins and Evolution’. Portuguese food, which had also been influenced by Judaic, Arabic and Roman cooking traditions, swiftly grew distinct from Spanish cuisine despite some common similarities they both still share today.

In the years after 1492, the Portuguese, without the resources at home to feed their growing population, set out to find new lands, establishing sugar plantations in Madeira and across the Caribbean, as well as territories in South America and Africa. In an extensive study of Luso-Asian populations across Asia, culinary historian and former head of the United Nations University Press, Janet P Boileau, describes the earliest voyages from Lisbon, around Africa and onwards to Asia. “The Portuguese voyages of exploration,” she says, “were undertaken by a small, economically challenged nation filled with Catholic zeal inspired by its liberation from centuries of Muslim rule. Discovery of India and the Spice Islands generated the profits that allowed a wealthy colonial society to develop.” Along with the explorers went olive oil, wine and other European staples, as well as cooking techniques and foods like corn, tomatoes, potatoes and chillies from the Americas, then known as the New World. These foods travelled east with the Portuguese as they were easily transported on long sea voyages and carried growing cultural significance to the explorers.

Life on the seas for Portuguese crews was far from idyllic. Rats ran amok through food supplies, bed bugs were rife and supplies were often so low, the sailors had to subsist on stale biscuits riddled with worms. The ruling classes on board, meanwhile, enjoyed most of the landed luxuries to which they were accustomed, often entertaining leaders they encountered on the voyages. As a result, many elite ingredients like port, elaborate pastries and expensive meats also made the trip. Much of the food that made it to the final destination – and in Macao’s case, this really was the end of a ship’s monumental journey across the globe – was dried, preserved in salt or sugar, or otherwise protected from spoiling. This impacted the types of foods that ended up being used in Macao, which was established in 1557. Dishes based around vinegar, spices and treats like ‘bacalhau’ – salted cod – became, it could be argued, the first examples of Macanese cuisine in history.

Fish and seafood were important in all the coastal communities that the Portuguese seafarers set up over the years. Other Portuguese staples including pork, salt, bread, sugar and vinegar played an equally important role and were added to the ingredient stable along with local ingredients unique to each trading port like Ceylon cinnamon – from Ceylon, now Sri Lanka – and coconut milk from Malacca, which is now part of Malaysia. But in Macao, how did this heavy Portuguese influence become the multi-layered Macanese cuisine of today?

Enter the dragon

Following its establishment in the 16th century, Macao was unlike any other Portuguese territory in the world. It was small and lacked arable land. Therefore, from day one the city learned to rely on imports, just as it does today. And the most readily available imports? Chinese food, from just over the border. Early Macanese cooks relied heavily on food coming in from China, thus contributing to the Chinese influence inherent in the cuisine even among the early Portuguese settlers. And it’s here that it can be argued that the ‘world’s first fusion cuisine’ began in earnest.

Boileau argues that the Portuguese – more than other European explorers at the time – were open to the new foods and traditions they encountered. Although they arrived in these foreign lands ill-prepared for the novel plants, ingredients and customs, they were more able to adapt than their northern European counterparts. This may be why we still see more of the Portuguese legacy in their former territories to this day. Boileau suggests they also had an easier time acclimatising to warm, humid conditions as they were used to the southern European climate. And she notes they were more open to racial mixing and the blending of cultures. Boileau explains: “Portuguese marriages with indigenous women helped demystify and destigmatise local foods while [the] native skill in preparing them increased palatability.”

Boileau argues that the Portuguese – more than other European explorers at the time – were open to the new foods and traditions they encountered. Although they arrived in these foreign lands ill-prepared for the novel plants, ingredients and customs, they were more able to adapt than their northern European counterparts. This may be why we still see more of the Portuguese legacy in their former territories to this day. Boileau suggests they also had an easier time acclimatising to warm, humid conditions as they were used to the southern European climate. And she notes they were more open to racial mixing and the blending of cultures. Boileau explains: “Portuguese marriages with indigenous women helped demystify and destigmatise local foods while [the] native skill in preparing them increased palatability.”

The Chinese influence shaped Macanese cuisine from its birth. Bread was particularly important in Macao where it was ‘readily available and cheap’, according to 17th-century merchant and writer Peter Mundy, who Boileau cites as a source. But there was far more in the way of carbohydrate-laden food to draw from in Asia. In short, a rare combination of openness to new experiences and a proud cultural persistence gave rise to a truly unique cuisine in Macao. Macanese cuisine took on all the elements of the spice routes and of Chinese cuisine, yet managed to also retain its strong link to the Iberian world.

Girl power

Today, Macanese cuisine faces challenges. For example, ‘balichão’ was a shrimp paste often made with krill crustaceans that originated after the Portuguese brought pastes from other ports to Macao. Locals in the city developed it as a special variant for the basis of countless dishes and it became, for hundreds of years, perhaps the most important of all Macanese concoctions. It was neither fully Chinese nor Portuguese, a true fusion of cultures that gave a unique taste to many classic Macanese dishes. But today, it’s largely disappeared from culinary creations. Maria João Ferreira, a board member at Casa de Macau, a Portuguese members’ club in Lisbon, describes balichão as ‘a very dear seasoning of the Macanese cuisine which is, sadly, about to disappear’. Some see it as a condiment that’s facing extinction due to, according to Ferreira, the lengthy fermentation process involved in its creation and the inconvenience of sourcing the tiny shrimp, which are the main ingredient, live from wet markets. As a result of culinary challenges like this, many cooks are now reaching for more readily available alternatives on supermarket shelves. Ferreira is concerned that, as a result, some Macanese recipes are becoming endangered, as the balichão is ‘the main sauce and seasoning’ which she claims Chinese fishermen taught the early Portuguese settlers to make.

Rufino Ramos, secretary-general of the International Institute of Macau, has been delving into the city’s historic recipes and speaking to Macanese families to discover the secrets of the past. He has not only been preparing foods but trying to find out why they evolved as they did. “You have to understand the cultural environment 150 years ago,” he tells us. “What was the role of women in the household?” Noreen Sousa is well placed to answer that question. The Macanese great-grandmother comes with a mighty reputation. She is an encyclopedia of Macanese cuisine and her recipes are frequently published in historical books.

“Many of these [Portuguese] sailors,” says Sousa, “intermarried with Chinese women from Macao, as well as Goan and Malay women. Many also married Southeast Asian women. The wives would cook their own dishes but also to try to please their husbands. They would make do with what they had to replicate the dishes their husbands were used to.” As a result, explains Sousa, the husbands and wives learned from each other’s cultures and used local ingredients as well as what was transported on the ships to create new dishes. Gradually a new cuisine was formed in the homes of Macanese families.

Ramos also sees the wives of early settlers driving the evolution of the cuisine. “The ladies,” he says, “because they didn’t need to work, they dedicated all their time to cooking. And they were competing with their neighbours, so they had to do the best, most elaborate dishes possible. They used very complicated ways to produce the dish, just to make it good.” Ramos says that the most important ingredients as Macanese cuisine evolved were balichão and tamarind – a tart fruit from the tamarind tree which is used as a spice and souring agent in curries, chutneys and bean dishes – but he too concedes that these ingredients are gradually being used less as they are now nowhere near as readily available as they once were.

“The Macanese curry used to have balichão and tamarind as two of its main ingredients,” says Ramos. “and they used fresh coconut milk which has a better taste than canned. But why coconuts when there are no coconut trees in Macao? Because they came from Malaysia.” Ramos says that these days, the legacy of the culinary rivalry between households makes it harder to move the cuisine forward. “Many of the families didn’t want to reveal their secrets,” he explains. “I’ve requested many families to reveal their dishes but many say that they are their grandmother’s recipes and they treasure them. It’s a very precious thing. Many of those secrets get lost.” Ramos gives the example of a grandmother putting Chinese wine in a fish pie to finish the dish – but only when no one was looking…

Minchi could be labelled the unofficial national dish of Macao. Believed to have descended from both the English and Goan communities in the city, the centuries-old creation features minced or ground beef or pork which is flavoured with molasses and soy sauce, and usually comes with a fried egg on top. It’s so iconic in Macao, we’ve put it on our front cover for this special gastronomic issue. Other classics we think of as quintessentially Macanese today – like tamarind-braised pork, perhaps – are only a fraction of the many unique dishes that once made up the world’s first fusion cuisine. Much has been lost to history, so only the recipes that were best translated into restaurant dishes in the city or appealed to the younger generations now comprising the Macanese cuisine that’s known and enjoyed across the SAR every day.

Generation next

Chef Antonieta Fernandes Manhão, commonly known as ‘chef Neta’, runs cooking classes to promote Macanese food in the city. She is an expert on the cuisine and has been, over the past 10 months, collaborating on a special ‘chá gordo’ menu with The Manor restaurant at the five-star St Regis Macao hotel in Cotai Strip. The tradition of ‘chá gordo’, which literally means ‘fat tea’ in Portuguese, became famous in Macao over the years due to it being seen as a grand take on the traditional high tea but often with more dishes and more gusto. And despite being uniquely Macanese, the tradition takes influences from all over the Portuguese trading routes. Boileau sees it as an archetype of the openness to new ideas that helped create Macanese cuisine in the first place. “Chá gordo exemplified the processes of culinary creolisation that lay at the heart of Luso-Asian cuisine,” she says.

Chef Neta knows all too well the importance of the feast, describing it as ‘one of the unique and rare cultural practices that we have to preserve’. She explains that after her grandmother passed away, she dedicated herself to studying and cooking Macanese food because she didn’t want to lose the family knowledge. “We don’t want the cuisine to disappear in the future,” she says. “If we do nothing, in 10 years it will be gone. Tourists come to Macao and eat Portuguese food and think they have tried Macanese food – but it’s not the same. We need to educate them on the real Macanese food.”

The ‘Godmother of Macanese Food’, centenarian Aida de Jesus, is part of the older generation passing on the traditions with absolute authenticity at her famous Macanese restaurant Riquexó, which sits next to Guia Municipal Park. She says: “All the Portuguese [who frequent here] know what they will get. If I die, they know all the dishes [here] and these dishes will continue.” Aida de Jesus’ daughter, Sonia Palmer, who runs the restaurant on a day-to-day basis, explains that the Macao government is trying hard to introduce Macanese food to tourists. She says that, bit by bit, more people are discovering what Macanese food really is all about. “I’m happy to see that nowadays, more restaurants are opening and making Macanese food,” she explains. “It will go on because it’s young people who are opening them. But I don’t think it will be on a very grand scale like French or Italian food.”

Another chef carrying the torch is Tertuliano de Senna Fernandes, who was born into a Macanese family with more than 250 years of heritage in the city. He says this makes him ‘proud to continue the Macanese traditions’. As a chef consultant in Macao and on the Mainland, he helps to preserve the traditions by passing them on faithfully to other chefs and restaurateurs. He is also the founder and chairman of the ‘Associação de Gastronomia Internacional de Macau’ – the Macao International Gastronomy Association – an organisation that promotes Macanese food traditions around the world. “Being a chef,” he says, “my passion is food and, in particular, Macanese food. So I try my best to learn and promote as many traditional recipes as possible. I put all my efforts into promoting Macanese food and traditions. I hope to see more Macanese restaurants in Macao and around the world.”

“If we stop preserving our culture,” continues Senna Fernandes, “then it will just disappear.” But he is positive about the future for Macanese cuisine, adding: “In the modern world, we record everything we do, so I’m hopeful our culture will continue to live on and inspire future generations.” Noreen Sousa is similarly optimistic that the cuisine will continue to be passed down. “I have a feeling it will continue through the family,” she says. “My children are passionate about maintaining their culture and connection to their roots. Even my grandkids are very keen. We made our own balichão this year. That was a lovely day, sharing the knowledge with the whole family.”

Luis Machado, president of the Confraria Gastronomia Macaense – literally meaning the ‘brotherhood of Macanese gastronomy’ – believes that preserving the cuisine is not a simple task but he says there is a huge global effort underway to keep the tradition alive. “For the past 13 years,” he says, “since the foundation of our association, we have been promoting Macanese food locally and in Europe with the help of the Macao Government Tourism Office. With the help of local Macanese chefs we are trying to teach young Macanese generations to learn how to cook as their ancestors did.”

Machado accepts that no one can predict the future but he is optimistic about what can be achieved. “I’m sure that Macanese cuisine will prevail,” he says. “It will be strongly supported by everyone in the hotel restaurant industry and with the efforts of the Macao government to preserve a unique culture in the region.” Rufino Ramos believes the key to keeping the cuisine alive is to pass the wisdom of the elders on to the next generation and allow them to add their personality to the recipes while preserving the fundamentals of the tradition. He adds: “What we need is to train the younger generation. Stimulate the interest to understand the Macanese food culture and try to devise some regenerated recipes. Organise some sessions and try to exchange some recipes with them – or even some secrets.”

Macanese cuisine, the world’s first fusion cuisine, is still enjoyed and celebrated in the city (and abroad – see our next feature over the page) after hundreds of years of evolution. It won’t go down without a fight as the younger generations seek to ‘reclaim’ this important – and tasty – pillar of Macanese culture, heritage and history. Multiple organisations, the government and a new generation of chefs are doing all they can to preserve the traditions born of such unique conditions. Their skills and knowledge are matched only by their passion for preservation. In these capable hands lies the fate of this storied culinary culture.

Dine out

Our pick of the most iconic Macanese dishes and where to eat them in the city

Tamarind-braised pork at Riquexó

The ‘Godmother of Macanese Food’ Aida de Jesus’ favourite dish. Made with pork shoulder or neck that’s braised with tamarind, balichão and wine, this dish has its roots in the vindaloo of Goa, which itself was a product of the fusion of Portuguese and Indian cuisines. Try porco tamarindo at Aida de Jesus’ iconic Riquexó – meaning ‘Rickshaw’ – restaurant.

African chicken at Restaurante Litoral

Galinha Africana is said to have been invented by the late chef Americo Angelo at the Hotel Pousada de Macau in the 1940s after he was inspired on a trip to Mozambique. Reminiscent of Portugal’s peri-peri chicken, the dish sees a spice-laden marinade on the grilled bird which is combined with a soothing coconut milk sauce. Authentic Macanese haven Restaurante Litoral in Taipa Village does a marvellously juicy version of the dish.

Minchi at La Famiglia

Made with minced pork or a mix of beef and pork, minchi is perhaps the most iconic of Macanese dishes. La Famiglia in Taipa Village, currently under the expert eye of chef Florita Alves, has been serving the dish for 44 years. The pork is seasoned with light and dark soy sauce and served with crispy cubed potatoes with a fried egg on top.

Fat tea at The Manor

Macao’s lavish version of an afternoon tea, ‘chá gordo’ was, is and probably always will be the city’s quintessential example of the fusion of influences that makes Macanese food so unique. Combining the idea of the British high tea, the Cantonese ‘yum cha’ and the Anglo-Indian tradition of afternoon ‘tiffin’, ‘fat tea’ is a resplendent celebratory meal of epic proportions. Dig in with friends at St Regis Macao restaurant The Manor.

Not quite Macauese

Two iconic Macao street foods that are hardly traditional Macanese but nevertheless deserve an important mention

Egg tarts at Lord Stow’s Bakery

Based on the Portuguese ‘pastéis de nata’ from the parish of Belém, near Lisbon, egg tarts were actually introduced to Macao by an Englishman, Andrew ‘Lord’ Stow, in 1989. Hardly traditional Macanese cuisine but they have become so ingrained into the fabric of the city that they can be said to be one of the cuisine’s most recent examples. Hand-moulded pastry cases are filled with a decadent mix of egg yolks, cream and sugar, and baked until crispy and caramelised on top yet still wobbly and unctuous in the centre. Of course, try them at Lord Stow’s Bakery in Coloane.

Pork chop buns at Tai Lei Loi Kei

Prepare to queue at Tai Lei Loi Kei in Taipa Village. This humble eatery has been serving delicious pork chop buns to the people of Macao for more than 50 years. Said to have originated from the ‘bifana’, a pork cutlet sandwich found all over Portugal, Macao’s version sees a juicy, well-seasoned slab of pork served in a freshly baked crusty roll. This popular snack is a street food staple for Macao locals and tourists alike.